Полная версия:

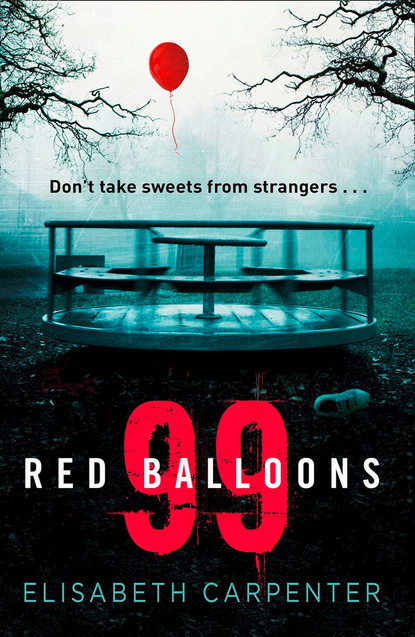

99 Red Balloons

‘Shall I get that for you?’ he says.

‘No. Let’s leave it. It’ll be a wrong number.’

Chapter Seven

I’m so tired. I can hardly keep my eyes open – even after having a glass of Coca-Cola. We’re back in George’s car. Everyone else is sitting in their cars too, ready to drive off the ferry. I wanted to sit in the front seat again, but he said they’re strict with things like this in Belgium. I’ve never been to Belgium so I didn’t know that.

I don’t dare ask about Mummy and Daddy again. ‘I’ve told you, they’re waiting for you,’ he said. I think he might be lying. I have to stop thinking about them or else I’m going to start crying again. George doesn’t like histrionics. I know that now.

I look out of my window. There’s another girl, probably older than me. I wave at her, but she just stares at me. She says something, but I don’t know how to lip-read. It’s probably to her mum because she looks at me too. She doesn’t smile either. She frowns and moves her head closer to the window. She looks at George and points.

‘Do you know that lady, George?’

His hands are gripping the steering wheel tight, like he’s scared we’re going to fall into the sea. He turns round and looks where I’m looking.

‘No.’ He hardly moves his lips. ‘For fuck’s sake, kid, what have you been doing?’

The woman is still looking at him; she looks at me again.

‘Smile and wave,’ says George, through his teeth.

He says it in a way that makes me think I really have to do as he says. Tears are coming to my eyes, but I smile my biggest smile – the one my gran always likes – and then I wave.

Slowly, the woman’s frown goes away and she smiles a small smile.

‘Thank fuck for that,’ says George.

I wish he’d stop saying naughty words.

The mummy looks at George. He rolls his eyes at her while smiling. She does the same. Adults can be copycats too.

A siren sounds; it makes me jump.

‘Right, kid,’ he says. ‘Doors are opening now. Make sure that seat belt is visible.’ He turns round again. ‘And don’t even think about looking at strangers again. There are some right nutters out there.’

It’s what my daddy says all the time.

Chapter Eight

Stephanie

It’s been forty-two hours. It feels like it’s getting darker in the mornings since she’s been gone, but I must be imagining it; the clocks don’t go back for another month. Grace will be back before then. She has to be.

The only person who’s slept longer than a few hours is Jamie and that’s because I made him. Even then he woke up upset, asking if Grace was back. The last helicopter patrol was last night. The sound of the propellers reminded us that Grace is out there somewhere. The police have searched the newsagent’s, playgrounds, car parks, her friends’ houses, neighbours’ houses, and places I didn’t know existed in town. It’s like she’s just vanished.

Between us, Mum and I have managed to straighten the house and get it looking as though it hasn’t been pulled apart. Unlike the initial search of the house, the police were more thorough yesterday. They tried, but didn’t put everything back as it was. We ran Emma a bath so she didn’t have to watch as we put things away.

People have been bringing round dishes of lasagne, sausage casseroles, pies, which cover almost every kitchen surface. We’ve only eaten the ones from the next-door neighbours. Mum said we shouldn’t trust any of the others as we don’t know where they’ve come from. I thought she was being picky, but when the Family Liaison Officer, Nadia, didn’t touch them either, they went in the bin.

There’s a knock at the door.

‘I’ll get it.’ Nadia gets up from her place in the kitchen. She sits near the doorway. We can’t see her, but she’s close enough to hear what’s being said in the sitting room. Perhaps she’s been told to listen to what we say in case one of us knows where Grace is. Whatever the reason for her being here is, at least we don’t have to answer the door any more.

‘Those bloody reporters,’ says Matt. ‘Can’t they leave us alone? If they’ve got nothing useful to tell us, they should just keep the hell away.’

He still won’t look at me for more than a few seconds. Should I have replied to his message the other night? What would I have said? Text messages are terrible when discussing something important, but we can’t talk properly here. There are too many people around us all the time.

‘It’s Detective Hines,’ says Nadia. She stands with her back to the fireplace and folds her arms.

‘Morning,’ he says. He looks as though he’s been wearing the same suit for days. His tie is about three inches from the top of his collar. There are bags under his eyes and stubble is beginning to shadow his face. ‘I want to make a television appeal.’

Emma’s sitting in the chair by the window, her knees pulled up to her chest, her arms wrapped around them. It takes her a few seconds to acknowledge that someone has spoken.

‘Pardon?’ Her voice is cracked; she hasn’t spoken for hours.

‘An appeal,’ says Matt. ‘They want us to go on television.’

‘You don’t have to do anything you don’t want to,’ says Hines, ‘but it might help jog people’s memories if they’ve seen anything out of the ordinary.’

‘Of course,’ she says. She looks away from the detective and resumes gazing through the window. She’s waiting for Grace. Any minute now she might walk back home. Emma wants to be ready for her, to open the door. ‘If we do it,’ she says, ‘I want Stephanie to be with me.’

Hines writes in his notepad again. ‘And you’re Grace’s aunt?’

Why does he keep asking me that? I thought detectives remembered everything.

‘Yes,’ I say.

Matt and I are on either side of Emma in the back seat. It’s the first time I’ve been in the back of a police car, but it’s not a panda, it’s a BMW. You can only tell it belongs to a police officer from the oversized radio and the gadgets on the dashboard. DS Berry is driving; Hines is in the passenger seat. Voices continuously come through on the police radio, but the detectives ignore them, keeping their eyes on the road ahead. Being in this car is another part of this nightmare that doesn’t feel real.

Mum has stayed with Jamie. Of course, she said she wanted to come, but Emma said, ‘It’s more important that Steph’s with me.’ I have no idea why she said that. Maybe she does remember something after all. Or perhaps she didn’t want Mum losing it in front of all the cameras and journalists. Mum gave in easily though, which was surprising. I don’t want my picture all over the newspapers, she said. I’ve not had a blow-dry for days. As though her looking her best was more important than finding Grace.

It’s the first time in daylight that we’re able to see all the teddy bears and tea lights in glasses left outside the gate. There are yellow ribbons tied in bows along the fence, and handwritten messages on the ground with stones on top to keep them from blowing away.

‘Don’t people usually leave candles for dead people?’ says Emma.

‘They’re candles for hope,’ I say, immediately realising how trite it sounds.

Matt’s staring out of the car window. He doesn’t seem to see or hear what we’re talking about. He’s wearing his work suit and his hair has gone curly, still wet from the shower. His reading glasses help to camouflage his red eyes.

After five minutes, we pull up outside the community centre. It’s where they host youth club discos and table tennis tournaments. Emma’s eyes squint when the car door opens and the strong September sun hits them.

The detectives get out and a uniformed policewoman drives the car away. Matt steps in front of me, taking Emma by the hand. I feel a stab of – what? Jealousy? Resentment?

Stop it, Stephanie. Get a grip.

There are a few photographers outside and several camera crews. One of the cameras has Sky News on the side. How did they get here so quickly? It was only in the paper yesterday, but I suppose most news is instant these days – they probably got here just after the story broke.

Detective Hines leads Emma and Matt towards the side door and I’m left at the front entrance. What am I supposed to do? Everyone outside is huddled in groups and I feel like a spare part. No one’s here to tell me what I’m supposed to do.

Three journalists – well, I assume they’re journalists; I’ve never met one before – are smoking cigarettes near the doorway. One of them narrows her eyes at me. She inhales the smoke like she’s hissing and blows it out like a sigh.

‘Are you a relative?’ she asks.

The other two – a man and a woman – look up.

‘No,’ I say, and rush through the door.

Chapter Nine

‘Won’t be long now, kid,’ I say to her.

She just nods, doesn’t talk much. It could’ve been worse – she could have been a right mouthy little shit, but she seems to be keeping in line so far. I haven’t told her my real name, not that I suppose it matters in the end. We are judged by our actions, not by our monikers. That’s what the shrink said anyway. They say a man acquires more knowledge when he’s inside, but I didn’t just learn the bad stuff. I was guided towards the right path. All right – I did ask Tommy Deeks how things like this are supposed to be done. But that was serendipity. He was sent to me for a reason.

‘Routines,’ he’d said. ‘Once you know someone’s routine, then you can intercept them at any time you see fit. And I don’t mean watching them for a few hours or a few days – you have to watch them for fuckin’ weeks. Their lives should be more important than yours – you eat, shit, sleep and dream about them. Then, my friend, it’s easy as fuck.’

All I needed was a name. And it just so happens that children have their own little routines too. Even in this day and age, kids are still allowed to walk the streets on their own. Their fuckwit parents should know better. There are too many weirdos out there. She’s lucky it’s only me that took her – there were some right filthy perverts inside. Not that we got to see them. Most of them would be killed if they put them with the rest of us.

Anyway. I digress.

This is probably the biggest thing I’ve ever done. It will be my salvation.

And God anointed Jesus with the Holy Spirit and with power. He went about doing good and healing all who were oppressed by the devil. For God was with him.

And if the ends justify the means …

She will be so pleased with me. It would be like none of all that bad stuff ever happened.

‘When will you take me to my mum?’

Her little voice almost made me shit myself. For a second I forgot she was there.

‘Not long now.’

There’s only so far I’m going to get away with that one. Another day or so, maybe. I’ve taken us the long way round, but we’ll be there soon. She’ll soon figure out that I’m not taking her to her mother. I look at her in the rear-view mirror – dressed in clothes I bought especially for her – her hair stuffed in a hat. Her cheeks look a bit red, but she’ll live. She looks just like her precious mummy. Although that bitch couldn’t even look me in the eye the last time I saw her.

She’ll have to soon enough though, won’t she?

Chapter Ten

Maggie

I’ve laid out all the cuttings from Zoe’s disappearance on the coffee table. There are only a few – there weren’t as many newspapers in 1986. Most papers used the photo of Zoe in her uniform – her first and last school photograph.

I try not to think about what she might have looked like if her picture had been taken every year after that. About how proud Sarah would have been of her. I try not to feel bitter every time I see her old school friends standing at the gates of the school down the road, adults now, waiting for children of their own. I simply let it stab me once, in the heart, before I bury it again. We used to talk about Zoe every day. I don’t get to talk about her any more. No one else knows her now.

I look at the clock. Jim’s late, but for once I don’t mind. It gives me time to look at all the different versions of her little face in the cuttings: small and grainy; black and white and brightly coloured, of which there’s only one. In the centre of them all I’ve placed the last photo of Sarah and Zoe together: my daughter and granddaughter.

I bury my face in my hands. It never gets any easier. It’s not the natural order. I’ve said that to myself a thousand times. I wish God would just take me to be with them. It’s too hard to be the only one left. Well, almost the only one.

Jim’s taps on the kitchen window halt the flow of my tears. I grab one of the cushions off the settee and soak up the wet from my face. This is why I hardly ever look at these pictures.

‘Where are you, Maggie?’

‘Where do you think I am? I’ve only two rooms.’

I place the cushion back next to me, but reversed.

Jim appears at the threshold and shakes off his coat.

‘You could’ve been in the lav,’ he says.

‘Well, you can’t ask where a lady is if you think she’s in the lav.’

‘It was just something to say,’ he says, ‘so you’d know I was here.’

He sighs and the settee sinks a little as he sits next to me. We don’t often sit like this together. I rub my right arm with my left hand to get rid of the tingling.

‘So this is what you’ve kept all these years,’ he says, looking at the pictures on the table.

He takes a folded newspaper from the inside pocket of his coat. The things he can carry in there. Last week he took out a tin of pease pudding because I’d never eaten it before. He should’ve kept it in there.

‘It’s today’s,’ he says. ‘She made the nationals.’

My intake of breath gives away my surprise.

‘Don’t look so shocked,’ he says. ‘I knew you’d want to read it.’

I take it from him.

‘I know. But don’t you think you’re indulging me? An old fool getting caught up in a story that’s nothing to do with her?’

He shakes his head. ‘You’re not the only one. They were all talking about it at the shop. And anyway, it’s not a story – it’s real life. You more than most know all about that. Stop being so ashamed about it.’

I feel myself flush. Am I ashamed? Ashamed we couldn’t find her? Guilty that she was taken in the first place? Or ashamed that I still think about her, that she might come back to me after everyone else has gone?

Jim picks up one of Zoe’s articles. ‘A sweet shop? Is that right?’

‘Yes,’ I say. ‘Like where this girl, Grace Harper, was last seen.’

Zoe should’ve been in the paper straight away. Perhaps she’d have been on the news all day too – they have news channels playing twenty-four hours a day now.

‘Have you been watching Sky News?’ asks Jim.

He read my mind.

‘I don’t have Sky News. Why would I want Sky? All I watch is Countdown.’

That’s a lie. I watch so much rubbish I couldn’t say. Channel Five do a true-life film every day that I usually end up crying to. I’d never tell Jim about that.

He winces as he stands up. ‘You’re the only person I know who keeps their remote control next to the television. What’s the bloody point of that?’

‘Mind your language,’ I say.

I wonder if Grace’s mother is waiting at the window, like Sarah used to.

‘You’ll have Freeview,’ he says. ‘Everyone does now. News 24 – it’ll be on there.’

I leave him to play with the remote control. I place all of Zoe’s articles back in the folder, except for one. It was the one that broke us: Search called off for missing Zoe Pearson.

We heard it from the police first. Newspapers weren’t as quick off the mark as they are now.

‘Every lead has been exhausted, Sarah,’ Detective Jackson said. ‘If we receive any new information, we’ll carry on the investigation. It’s not closed, it’s still open.’

I feel a drip on my hand and realise it’s from my face.

Jim turns and glances at me.

‘There you go,’ he says, handing me the remote. ‘It should be repeated any minute, it’s nearly on the hour.’

He pretends not to notice, Lord love him. That’s what we’ve always done, people our age: ignore things. Sarah used to tell me off for it. ‘For fuck’s sake, Mother, this isn’t the 1950s. People talk about things now – important things.’

Thinking about it thumps me in the chest. I beat myself up about it every day: my hypocrisy. It was so hard to talk about Zoe then. But if Sarah were here now I’d be different. I’d talk about Zoe all the time.

‘She used to sit by the window, did our Sarah,’ I say. ‘Waiting and waiting, never leaving the house. I have to be here when she gets back, she said. Every day. For years.’

‘Aye,’ says Jim.

I’ve told him many times and he always listens as though it’s the first. He reaches over and pats my hand. I look into the little girl’s eyes in the newspaper he brought me. Grace Harper’s eyes.

‘This one’ll be different.’ I say to her, ‘They’ll find you, love. Just you see. It’s different nowadays. People have their cameras everywhere.’

Jim carefully picks up Zoe’s article from the coffee table. ‘Is it okay if I …?’

‘Of course.’

He takes his glasses, which are on a chain around his neck, and perches them on the end of his nose. He tuts several times, shaking his head. He removes his glasses and rests them on his chest.

‘These sightings of your Zoe,’ he says. ‘Where were they?’

‘Cyprus, France, Spain.’ I reel off the list.

‘Really? How could they have done that?’

‘Who knows – they might have hidden her.’

Jim smiles at me kindly, like most people used to when I dared to believe Zoe was still alive. He looks up at the television.

‘It’s the appeal.’

A policeman in a suit is reading from a piece of paper. Next to him are, I presume, Grace’s parents. The mother has her head in her hands; the father comforts her, his arm around her shoulders.

My heart beats too fast, I wrap my arms around myself – I’m so cold, I’m always cold.

‘They look young,’ says Jim.

‘People do these days. Must be in their early thirties, I imagine. Though I can’t see her face properly. My mother looked fifty when she was thirty.’ My mouth is talking without my mind thinking. ‘Those poor people.’

It cuts to a photograph of a school uniform laid out on a table.

‘These are the clothes Grace was wearing, although if someone has taken her, she might not be wearing the same ones.’

Jim tuts. ‘Course she wouldn’t be wearing the same clothes. But you know, Maggie, I know I shouldn’t say this, but what if someone’s taken her, and just killed the poor little mite?’

I sigh loudly in the hope it’ll shut him up. Even though I’ve thought the same thing myself.

The appeal must have been taped earlier as the news article cuts to a shot outside: a village hall or a community centre. I see the mother’s face for the first time – her friend, or perhaps her sister, holding her by the elbow.

I get up slowly and walk to the television. ‘She’s a bonny one, isn’t she?’

He doesn’t answer.

‘Would you pause it, Jim?’

He presses the button several times.

‘Come on!’

‘I’m bloody pressing it.’

He did it. The picture’s frozen. I get closer to the screen, bending down to look at her face. My knees go weak. I drop to the carpet.

I can’t breathe properly.

Jim’s at my side.

‘Have you had a turn? Shall I fetch the doctor?’

I take several breaths before I can speak and shake my head.

‘I’m fine. Pass me that picture.’ I point to the mantelpiece, but he picks up the one facing the wall – the one I rarely look at. ‘Not that one, the one on the right.’

He grabs it and hands it to me. I hold it next to the pretty face on the television.

‘Look.’

He squints.

‘Put the glasses on your face, man.’

As he does, he brings his head next to mine, just a few feet from the television.

‘Well, would you look at that,’ he says. ‘She’s the double of your Sarah. But that’s impossible, she’s—’

‘I know, I know. But it could be …’

Jim frowns. ‘What are the chances of that? It can’t be.’

My shoulders slump. ‘I know. But it might. It might be Zoe.’

Chapter Eleven

Stephanie

Grace has been gone for almost three days. If the police have any new information from the television appeal yesterday, then they haven’t updated us.

Mum has been making a fuss of Emma, though I don’t begrudge it of course, not now Grace is missing. She’s indulged her ever since she came to live with us. Emma arrived with only a little rucksack. I had just turned eleven and she was ten and three quarters. Her hair was straggly, like it hadn’t been washed for weeks, but it didn’t smell horrible – it was sweet, like sticking your nose in a bag of pick ’n’ mix from the cinema. Her knees were dirty though, and her skirt had food stains all over it. Mum had warned Dad and me that Emma might be in a right state because she’d been alone in the house for at least three days until her neighbours had noticed. ‘Her mother ran away with a man half her age,’ Mum said. ‘All she had left in the cupboards was a tin of Golden Syrup and a can of prunes, which she couldn’t even open.’

Emma and I didn’t speak for four days. I was a little scared of her, plus she was given my bed under the window. It had been my favourite place to be. I could pull back the curtains and watch the stars when I couldn’t sleep, imagining I was somewhere else. It was only after I heard her crying for the fifth night in a row that I tried to talk to her.

‘Do you miss your mum?’ I whispered.

I heard the pillow move. I took that as a nod.

‘Do you want me to turn the lamp on?’

‘Yes please,’ she said, as quiet as anything.

I flicked on the light and I’ll never forget her face. The skin around her eyes was so puffy I could barely see them. Her hair was stuck to her cheeks from the wetness of her tears.

I opened my covers. ‘Do you want to come in with me?’

She nodded and almost dived into my bed. Her head snuggled into my chest and she put her arms around me. I turned off the light, and put my arm around her shoulders. I looked to the window. The curtains were open and I could see the stars. Within minutes she was fast asleep.

The memory is so vivid, I almost forget where I am. I give myself a shake – now isn’t the time to get lost in the past. I go into the kitchen to check on Jamie. I’ve kept him off school and he’s been on his laptop all morning, reading what he can find about Grace.

‘They’ve created a Facebook page,’ he says.

‘Who has?’

He shrugs. ‘I don’t know the names. Do you?’

He points to the screen. I haven’t used Facebook for ages.

‘I’ve no idea. They sound Scottish. How can they even create a page when they don’t know us?’

‘Anyone can create a Facebook page.’

‘That’s a bit creepy.’

He shrugs. ‘It’s just what happens.’

He scrolls down the page, which is filled with well-meaning messages: I hope they find her. Praying she gets home safe. Amongst them are comments from her school friends: Missed you at school today, hunnie. They’re written as though Grace might actually read them. Who would let their eight-year-old child write on Facebook?

‘What’s that?’ I look closer at the screen.

‘Ah yeah. Just some random psychic woman.’

‘Doesn’t she realise how upsetting things like that are?’

‘Things like what?’ It’s Mum.

‘Don’t sneak up on us like that.’

‘What’s going on?’ she says. ‘Is that Facebook? You know what I’ve said about that.’