Полная версия

Полная версияObservations on the Diseases of Seamen

Transcriber’s Keys:

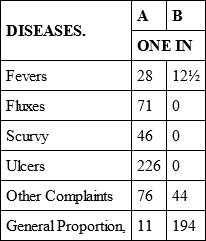

A Proportion of those taken ill in the Course of the Month.

B Proportion of Deaths, in relation to the Numbers of the Sick.

The proportion of deaths to the whole number was one in thirteen hundred and sixty-one. About one ninth of all the sick were sent to the hospital.

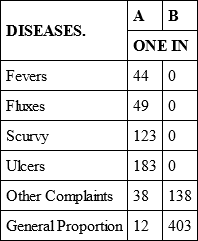

Table, shewing the Prevalence of Sickness and Mortality in the new Squadron, in MarchTranscriber’s Keys:

A Proportion of those taken ill in the Course of the Month.

B Proportion of Deaths, in relation to the Numbers of the Sick.

The proportion of deaths to the whole number was one in four thousand and eighty-seven. About one in eleven of all the sick were sent to the hospital.

The main body of the fleet remained at Barbadoes till the 12th of January, when they went to cruise to windward of Martinico, in order to intercept a French squadron expected from North America. This cruise lasted four weeks; and intelligence being received of the enemy’s having taken a different route, the whole fleet bore away for St. Lucia, where it came to an anchor on the 8th of February.

In the course of the three months above mentioned, we see the two squadrons approaching to each other, in point of health, till they became pretty equal and similar; and the new squadron became even somewhat more healthy than the old.

The increase of fevers in the old squadron was owing to two causes. One was the importation of new-raised recruits brought from England by some ships that arrived in the beginning of January. These were distributed to such ships as stood most in need of men; and being very dirty and ill cloathed, were likely to harbour infection. They were evidently the cause of sickness in the Warrior and Royal Oak; for these ships were before that time healthy, and the fever began with these strangers, and spread amongst the former crew. It is remarkable that the ships that brought them from England were not affected by them.

It was caught in the Royal Oak from six men that came from England in the Anson, which men, though first put on board the Namur, communicated no fever there, having been kept separate from the rest of the men; but being sent to the Royal Oak, they were themselves first taken ill with a fever, which afterwards spread to about thirty of the other men. What was singular in this fever was, that the eyes and skin of all that were affected by it became yellow, though without any particular malignancy; for only two died on board, and one in the hospital. There was one whose skin was very yellow, yet his complaint was so slight as never to confine him to his bed.

The other cause of the increased proportion of fevers in the old squadron was, the great number of these complaints that arose in the Magnificent. This ship having been sent on a cruise about the middle of February, and the weather being rainy, squally, and uncommonly cold, for the climate, many fevers of the inflammatory kind appeared. During this cruise she made prize of a large French frigate, called the Concord, and the greater part of the prisoners being taken on board, the fever from that time assumed a different type, with new and uncommon symptoms; for, instead of being inflammatory and requiring bleeding, as before, it became more of a low, putrid kind, and was attended in most cases, if not in all, with a continual sweating; so that, instead of evacuations, the remedies that were found most effectual were the Peruvian bark, blisters, and opium. Thus we see fevers variously modified according to men’s constitutions, the state of the air, and the noxious effluvia of the strangers that intermix with them.

We find the proportion of fluxes increasing in the new squadron in January and February, as they had formerly done in most of the ships soon after their arrival from England. They were observed also to prevail principally in those ships that had formerly been most subject to fevers, and not to arise till the fever had subsided. They were found, for instance, to arise later in the Suffolk, where the fever was obstinate and malignant, than in the Princess Amelia, where the fever had been at one time general and fatal, but not so violent and lasting as in the other.

The four ships that were sent to cruise near Guadaloupe continued at sea for seven weeks; and it was owing to the prevalence of scurvy in these and in the Magnificent that the proportion of that disease was greater at this time in the old than in the new squadron.

The fleet remained at St. Lucia till the accounts of the peace arrived in the beginning of April. The service was then at an end, and I returned to England with the first division of the fleet, which sailed from St. Lucia on the 12th of April, under the command of Rear-admiral Sir Francis Drake, who was at this time in extremely bad health, and requested me to accompany him.

PART I

BOOK III

CHAP. I

Hospital at Gibraltar, 1780 – at Barbadoes, 1780 – Causes of Mortality from various Diseases – Accidents – the Hurricane – Wounds – Amputations – Scorches – Fluxes very apt to arise at the Hospital – Proportion that were received and died at Antigua – St. Christopher’s – St. Lucia, and at Barbadoes, 1782 – at Jamaica, 1782 – at New York, Autumn, 1780 – 1782 – General View of the Admissions and Mortality at all the Hospitals during the War.

In order to judge of the loss sustained by disease, in the course of that service of which a relation has been attempted, the sick sent to the hospitals must be taken into account. I shall, therefore, give a short view of the different diseases admitted, and their mortality, at the several hospitals connected with the fleets in which I served. This will serve also to illustrate the different effects that different situations have upon the health and recovery of men22.

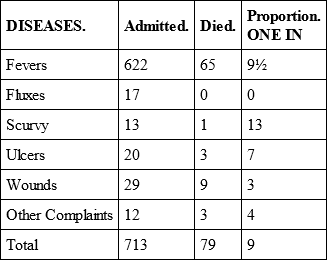

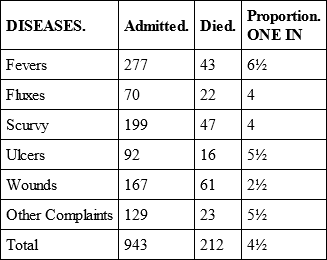

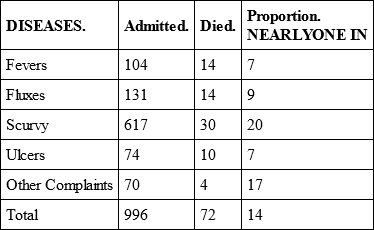

The fleet which effected the first relief of Gibraltar, under the command of Lord Rodney, consisting of twenty ships of the line, arrived there in the third week of January, 1780, after a passage of three weeks and a few days from England, in which they had an action with the Spanish fleet, and obtained a victory over them, on the 16th of that month. The whole fleet, except one ship, sailed from Gibraltar on the 13th of February, and while it lay there, the diseases sent to the hospital, and their respective mortality, were as follows23:

24This comprehends not only the deaths in the time the fleet remained there, but all that happened afterwards. The mortality, from wounds and ulcers, is greater than might be expected in so fine a climate, and at the coolest season of the year; but as the place was then besieged, the sick and wounded could not be supplied with those refreshments that were necessary to the recovery of the men, and wounds and ulcers are complaints very apt to be affected by the quality of the diet.

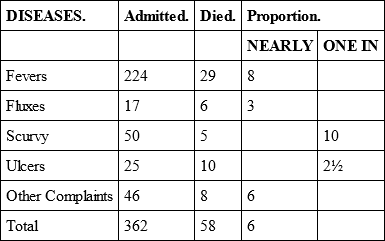

The following is an Account of the Men admitted at the Hospital at Barbadoes in the Campaign of 1780, that is, from the 16th of March till the end of June:

The fevers were chiefly from the five line-of-battle ships that came immediately from Europe in March. Upon their arrival they sent on shore one hundred and ninety-three men ill of fevers, only one with the flux, fifteen with the scurvy, and five with ulcers.

When these ships returned to Barbadoes in May, along with the rest of the fleet, the greater part of the sick were then also on board of them. By that time the flux and scurvy had broke out. The former prevailed chiefly in the Terrible; the latter in the Intrepid. That part of the fleet which we found on the station sent on shore a very small proportion of all the classes of complaints, except wounds.

Of the wounds, nineteen were amputations, of which there died nine, mostly of the locked jaw. There were forty-six scorched by gunpowder, of whom there died fourteen; so that, besides those who were killed outright, and those who died on board in consequence of accidents of this kind, before they could be sent to an hospital, about one fourth of all the wounds, and the same proportion of all the deaths from wounds, at the hospital, was owing to this cause. This circumstance ought to induce commanders to take every precaution to prevent such accidents. In the subsequent part of the war they were less frequent, in consequence of that greater caution, and more accurate method of working great guns, which were acquired by practice and experience25.

In the account of the mortality, I have included only such as died before the 1st of January, 1781; for if any were carried off after that time, it was most probably by some incidental complaint. There were sixty-five of them at that time remaining, and they were chiefly men disabled by lameness waiting for a passage to England as invalids.

Out of the twenty-three that were killed by the fall of the house in the hurricane on the 10th of October, eight were of the number above accounted for; but these are not included in any of the classes of deaths.

The mortality among the men admitted at this time was greater than what occurred afterwards in any of the hospitals that I attended, except that at Jamaica. The principal cause of this was, that as the fleet was so much greater than had ever been known here before, there was not suitable accommodation for such numbers as it was necessary to send on shore, and we had not then fallen on the method of supplying refreshments to the men on board of their ships. The circumstance by which the men suffered most was, the great crowding which the want of room made necessary. There is here no public building appropriated for an hospital; so that this, as well as every thing else, being found by contract, and the number of sick being so much greater than it was usual to provide for, the whole was at this time conducted in a manner not very regular.

It appears that the greatest mortality in any class of disease was that of the fluxes, of which the greatest number sent to hospitals are such as have languished for some time under this disease, in which state it generally proves fatal in the West Indies, in consequence of incurable ulcers in the great intestines, to which the heat of the climate, as well as the scorbutic habit and sea diet, is particularly unfavourable. But the whole of the mischief arising from it does not appear in the table; for it was the most apt of any disease to supervene upon other complaints which were under cure at the hospital. It more particularly attacked those who were recovering from the scurvy, and was the cause of the greater number of deaths under this head in the table. It was found to be more contagious than fevers, either because the men’s constitutions were more predisposed to it, or, perhaps, because the infectious matter of it being more gross and less volatile, it is not so readily dissipated by the heat of the climate; for, either from this, or some other circumstance, infectious fevers are not so easily generated, nor so apt to spread, as in Europe. That these fluxes were owing to infection may be inferred from hence, that, when men ill of the scurvy were cured on board of the ships they belonged to, they were not liable to this disease, neither did they prevail at these hospitals afterwards, when great care was taken to separate infectious diseases from the others.

The only regular hospital on this station is that at Antigua. This island being the seat of the royal dock yard, there is an established hospital in time of peace as well as war. It so happened, that great fleets never came here to put their sick and wounded on shore, as at Barbadoes; so that the greater number of those received into it were from single ships that came to careen. As there was, therefore, less necessity for crowding, and as the slighter cases could be admitted, there was a less proportion of deaths here than at most of the other hospitals.

There were two other establishments for the reception of the sick and wounded on this station, but they were only temporary. These were at St. Lucia and St. Christopher’s, where the men being received in great numbers at a time from large fleets, and as there were accommodations only for the most urgent cases, the mortality approached more nearly to that of Barbadoes. There died at St. Christopher’s, in the years 1780 and 1781, in the proportion of one in six, and at St. Lucia, in the same time, one in five and a half, or two in eleven. The air of the hospital at St. Lucia was remarkably pure, and this degree of mortality was owing to the sick having been accommodated in tents and huts. In the two last years of the war, when an hospital was built, and regularly established, the mortality was not much above one half of this.

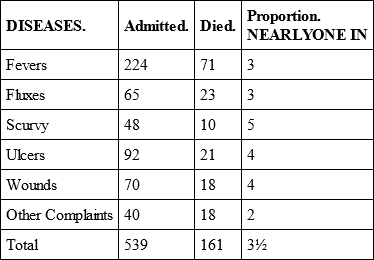

Some authors have endeavoured to form an estimate of the success of practice from the different rates of mortality; but this is extremely fallacious; for the fatality of diseases will depend on their violence, the proportion of deaths being very different in cases that are slight, from what it is in those that are dangerous. We shall take a view, however, of the hospital at Barbadoes at another period, in which there seemed little or no difference in the violence of the disease, and when the superior success seemed to be owing to the hospital’s not being so crowded, and to the better attendance and treatment of the sick. The following is a view of the diseases that were admitted in the last three months of the year 1782, the greater part of which were landed from the reinforcement of eight ships of the line that joined the fleet at Barbadoes in the beginning of December:

It happened on this, as on the former occasion, that none were sent on shore but such as were very ill, or had contagious complaints, the rest being provided with refreshments on board of their ships. There were no wounds at this time, but there was a greater proportion of fevers; so that the complaints, upon the whole, might be said to be about equally dangerous. The mortality now was, however, considerably less, and this is to be imputed to the more favourable situation of the hospital, which I did not allow to be overcrowded; and the men had all manner of justice done them in point of attendance and accommodation.

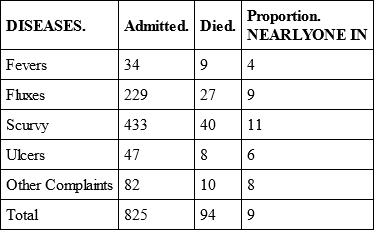

I shall give another example of the same kind in the hospital at Jamaica, when our fleet went there after the battle of the 12th of April. All the men accounted for here were landed from the fleet under Lord Rodney in May, June, and July, 178226.

This uncommon degree of mortality was not owing to the bad air of the place, for Port Royal is naturally as healthy as most parts in that climate; nor was it owing to bad accommodations, or to neglect of any kind; but is imputable entirely to this circumstance, that the hospital being extremely small, those only were sent to it who were very ill. There were at this time upwards of forty ships of the line at Jamaica, and an hospital, containing only three hundred beds, could afford but a very inadequate relief. Some officers are unwilling that any man should die on board of their ships, for fear of dispiriting the others; and many were sent to the hospital, in the most desperate stage of sickness, that they might there die.

There cannot be a stronger proof than this of the fallacy of judging of the success of practice by the proportion of the deaths; for the sick on this occasion were better accommodated, better provided for in every respect, and as regularly attended, as at any other period of my service in the West Indies, yet the mortality was greater than at any other time.

Having given instances of the common rate of mortality in hospitals in Europe and the West Indies, I shall next give examples of the success we had in North America, when the fleet was there in the autumns of 1780 and 1782.

Account of the Sick landed at New York from the West-India Fleet, consisting of eleven Ships of the Line, in Autumn, 1780.

Account of the Sick landed at New York from the West-India Fleet, consisting of twenty-six Ships of the Line, in Autumn, 1782.

The difference of mortality here, from what occurred in the West Indies, is partly imputable to climate, and partly to the smaller number of acute diseases. In the two accounts last stated, the difference in favour of the latter seemed chiefly to arise from the superior attention to the sick, and the better treatment of them. It was mentioned before, that in autumn, 1782, at New York, they were better supplied, both at hospitals and on board of their ships, with every thing that could be wished, and that on this occasion almost every scheme I had proposed was realised. The extraordinary success in the scurvy was owing to the great quantities of vegetables that were supplied; for several fields of cabbages had been planted in the neighbourhood of the hospital for the use of the sick. This was owing to the humane attention of Admiral Digby, who had also caused cows to be purchased to supply the hospital with milk. Cleanliness, and the separation of diseases, were also strictly attended to; and I am persuaded that many of the scorbutic men were saved by keeping them separated from the fevers and fluxes; for it has been observed, that men ill of the scurvy, or recovering from it, are very apt to be infected, particularly with the flux.

It appears, that the disease in which climate makes the greatest difference is the flux. It was observable, that though the dysentery at this time was more fatal on board of the ships at New York than in the West Indies, yet it was less so at the hospital. The cause of this seems to be, that the acute state of this disease, of which men die on board before there is time to remove them to an hospital, is more fatal in a cold climate; but when it becomes more protracted, which is the case with most of the cases sent to hospitals, they then do much better in a cold than in a hot climate.

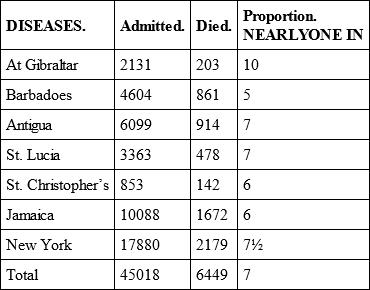

I shall here subjoin an account of the numbers that were admitted, and died, during the whole war, at the hospitals of the different parts at which the fleets I was connected with touched.

I have been able to calculate the numbers of deaths from disease in this great fleet, both on board and at hospitals, during the period of my own service, which was three years and three months, and they amounted to three thousand two hundred27 independent of those that were killed and died of wounds.

There died of disease in the fleet I belonged to, from July, 1780, to July, 1781, about one man in eight, including both those who died on board and at hospitals28. But the annual mortality in the West-India fleet, during the last year of the war, that is, from March, 1782, to March, 1783, was not quite one in twenty29. This difference was partly owing to the general increase of health in fleets as a war advances, partly to some improvements in victualling, and partly to better accommodations as well as regulations in what related to the care of the sick.

Though the mortality in fleets in the West Indies is, upon the whole, greater than in Europe, yet it has so happened, that, in the late war, the fleet at home has, at particular periods, been considerably more sickly than that in the West Indies was at any one time. I was informed by Dr. Lind, that, when the grand fleet arrived at Portsmouth in November, 1779, a tenth part of all the men were sent to the hospital. It appears30, that in the years 1780 and 1781, a period at which the fleet in the West Indies was most sickly, the medium of the numbers on the sick list was one in fifteen, and many of these were very slight complaints; whereas, in the fleet alluded to in England, the diseases were mostly fevers, and so ill as actually to be sent to the hospital. It appears likewise, that there was the greatest proportion of sick in our fleet when it was on the coast of America in September, 178031. This difference is owing to the greater prevalence of the ship fever, and of the scurvy, in a cold than in a hot climate.

With regard to the mortality at hospitals, the comparison is greatly in favour of those in England. This is owing to the greater regularity, and the better accommodation and diet, which an hospital at home admits of, as well as to the difference of climate. It has also been mentioned, that, on most occasions, the hospitals I attended abroad were so limited as to contain only the worst cases, in consequence of which there would of course be a greater proportional mortality than in the great hospitals of England.

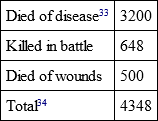

The following is an account of the whole loss of lives from disease, and by the enemy32, in three years and three months, in the fleets and hospitals with which I was connected:

Примечание 133

Примечание 234

PART II.

of the

CAUSES of SICKNESS in FLEETS, and the

MEANS of PREVENTION

In the year 1780 I printed a small treatise for the use of the fleet, containing general rules for the prevention of sickness; and this part of the work is chiefly taken from it.

My own opportunities of experience, as exhibited in the preceding Part, have been sufficiently extensive to suggest many observations on this subject; but as my object is utility, rather than the praise of originality, I shall not confine myself to these. Great part of what is to be advanced is taken from books35 and conversation, as well as my own experience, my design being to exhibit a concise view of all the discoveries on this subject that have come to my knowledge. I have assumed nothing, however, from mere report or testimony, having had opportunities, from my own observations, of verifying or disproving the assertions of others.

More may be done towards the preservation of the health and lives of seamen than is commonly imagined; and it is a matter not only of humanity and duty, but of interest and policy.

Towards the forming of a seaman a sort of education is necessary, consisting in an habitual practice in the exercise of his profession from an early period of life; so that if our stock of mariners should come to be exhausted or diminished, this would be a loss that could not be repaired by the most flourishing state of the public finances; for money would avail nothing to the public defence without a sufficient number of able and healthy men, which are the real resources of a state, and the true sinews of war.

In this view, as well as from the peculiar dependence of Britain on her navy, this order of men is truly inestimable; and even considering men merely as a commodity, it could be made evident, in an œconomical and political view, independent of moral considerations, that the lives and health of men might be preserved at much less expence and trouble than what are necessary to repair the ravages of disease.

It would be endless to enumerate the accounts furnished by history of the losses and disappointments to the public service from the prevalence of disease in fleets. Sir Richard Hawkins, who lived in the beginning of the last century, mentions, that in twenty years he had known of ten thousand men who had perished by the scurvy. Commodore Anson, in the course of his voyage of circumnavigation, lost more than four fifths of his men chiefly by that disease. History supplies us with many instances of naval expeditions that have been entirely frustrated by the force of disease alone: that under Count Mansfeldt in 1624; that under the Duke of Buckingham the year after; that under Sir Francis Wheeler in 1693; that to Carthagena in 1741; that of the French under D’Anville in 1746; and that of the same nation to Louisbourg in 175736.