Полная версия

Полная версияObservations on the Diseases of Seamen

The second cause of the prevalence of sickness, while the fleet was at Jamaica, was, the watering duty, which was carried on at Rock-fort, about three leagues from Port Royal. It was the practice of many of the ships to leave the water casks on shore all night, with men to watch them; and as there is a land wind in the night, which blows over some ponds and marshes, there were hardly any of the men employed on that duty who were not seized with a fever of a very bad sort, of which a great many died. The ships that followed a different practice were somewhat longer in watering; but this was much more than compensated by their preserving the health and saving the lives of their men.

The land wind which blows on the shore in the night time, is a circumstance in which Jamaica differs from the small islands to windward, over which the trade wind blows without any interruption: but though this land wind blows upon Port Royal from some marshes at a few miles distance, it does not seem to produce sickness, for it is a very healthy place, and several of the ships enjoyed as good health as in the best situations on the windward station. The bay which forms this harbour is bounded towards the sea by a peninsula of a singular form, being more than ten miles in length, and not a quarter of a mile broad at any part. Great part of it is swampy and overgrown with mangroves, and though of such small extent, we fancied that some of the ships that lay immediately to leeward of this part were more sickly than those that were close to the town of Port Royal, which stands at the very extremity of this long peninsula upon a dry, gravelly soil.

The weather this month was uniformly dry in port; but at sea the air was moist and hazy. Between Jamaica and Hispaniola, where part of the squadron was left to cruise, dead calms prevailed; and this, joined to the moisture of the air, was probably what caused the flux to prevail chiefly in this part of the fleet. At Port Royal, on the contrary, there was a strong dry breeze, which set in every day about nine o’clock in the morning, and blew all day so fresh, that there was frequently danger in passing from one ship to another in boats. This is called, in the language of the country, the fiery sea breeze, an epithet which it seems to have got not from its absolute heat, but from the feverish feeling which it occasions by drying up the perspiration. It was remarked, that this breeze was stronger this season than had ever been remembered; and it sometimes even blew all night, preventing the land breeze from taking its usual course. This year was farther remarkable for the want of the rains that were wont to fall in the months of May and June. We shall have occasion to remark hereafter, that this was a very uncommon season also in Europe and America. The heat, by the thermometer, this month, on board of a ship at Port Royal, was, in general, when lowest in the night, at 77°, and when highest in the day, in the shade, at 83°.

There was a considerable increase of scurvy in this month, compared with the former months of this campaign; but very inconsiderable, compared with what had occurred in cruises of the same length in former years. The last division of the fleet had been at sea seven weeks, all but one day, when it arrived at Port Royal; and though the scurvy had appeared in several of the ships, it did not prevail in any of them to a great degree, except in the Nonsuch. Out of fourteen deaths which happened in the whole fleet from this disease, in May, seven of them were in this ship, and several were sent from her to the hospital in the last and most desperate stage of it. But, upon the whole, the cases of the true sea scurvy in the fleet, in general, were few and slight, and a great many of those given in the reports under the head of scurvy, were cutaneous eruptions or ulcers, not properly to be classed with it.

The cruise in the preceding year to windward of Martinico, may be compared with that in May of this year; for the fleet in both cases had been at sea about the same length of time. But the comparison is very greatly in favour of the latter, which is most probably to be imputed to the plentiful supply of melasses, wine, sour krout, and essence of malt. But no adequate reason that I could discover can be assigned for the prevalence of it in the Nonsuch to a degree so much more violent than in the other ships; and it was here farther remarkable, that it attacked every description of men indiscriminately; for I was assured by the officers and by the surgeon, that not only the helpless and dispirited landsman was affected, but old seamen, who had never before suffered from it on the longest cruises. I have been led by this, and some other facts, to suspect that there may be something contagious in this disease.

JUNEThe greater part of the fleet remained at Jamaica during this month, refitting and watering. Twelve ships of the line were sent to sea on the 17th, under the command of Rear-admiral Drake, but not being able to get to windward on account of the fresh breezes that prevailed, they returned to Port Royal on the 28th. Such of these ships as were sickly, became more healthy while at sea; but some bad fevers arose, particularly in the Princessa; and it is a curious circumstance, that these fevers attacked only those men who had been on shore on the watering duty; from which it would appear, that something caught or imbibed, which is the cause of the fever, lies inactive for some time in the constitution, some of the men not having been affected for more than a week after they had been at sea.

The weather continued dry and windy, as in the former month; but the heat was in general about two degrees higher, the thermometer varying from 79° to 84½°.

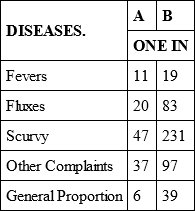

Table, shewing the proportional Sickness and Mortality in JuneTranscriber’s Keys:

A Proportion of those taken ill in the Course of this Month.

B Proportion of those who died, in relation to the Numbers of the Sick.

The proportion of deaths in relation to the whole numbers on board, was one in one hundred and thirty-eight.

There was only one in thirty of the sick sent to the hospital in the course of this month.

There was an increase both in the numbers and fatality of fevers. This increase was chiefly in that sort of fever which depends on the air and climate, the greater part of which was caught on the watering duty. There was a diminution of those fevers depending on infection, and the foul air of ships, which arose in the French prizes. The care that was taken in purifying these ships was very effectual; for only four died this month in the Ville de Paris, and fewer also were sent to the hospital than in May. The increase of the other kind of fever was chiefly owing to there being a greater number of ships in port, the crews of which were employed in watering, and partly, no doubt, to the increase of heat in the weather. The ships in which the fevers were most fatal were the Monarch, the Duke, the Torbay, and the Resolution. The sickness in the Duke was still in a great measure owing to the same infection that had hitherto prevailed; for this ship had never been cleared of the infectious fever, for want of room at the hospital. That which broke out in the Torbay was also of the low infectious kind, few of them having the symptoms of that which is peculiar to the climate, which prevailed in the other ships. This ship, though formerly very subject to infectious complaints, had been remarkably healthy for some time past; but it would appear that there was a large stock of latent infection, which shewed itself from time to time.

Some ships, particularly the Montague and Royal Oak, had no increase of fevers or other complaints, though the one lay in port for seven, and the other for eleven weeks, and were more or less exposed to the causes of sickness which affected the rest of the fleet. This is a proof, among many others, that a particular combination of causes is necessary to produce a disease: no single one, however powerful, being sufficient, without the concurrence of others. What seemed to be wanting here was the predisposition requisite for the admission of disease into the constitution; for the ships that enjoyed this happy exemption were such as had long-established and well-regulated crews, accustomed to the service and climate.

There had been this month a diminution both of the numbers and mortality of fluxes, which is agreeable to what was before remarked, that fevers were more apt than fluxes to prevail in the bad air of a harbour16. It was also before remarked, that there were few or no fluxes in those ships in which the fever was most malignant; and now that the fever began to grow more mild in the French prizes, the flux began to appear. In the Barfleur, Duke, and Namur, both diseases seemed to prevail equally; but the fevers, though numerous, were more of the low nervous kind than bilious or malignant; and the fluxes chiefly attacked those who were recovering from fevers. We may farther remark, that these three men of war were three-decked ships, of 90 guns, the crews of which being more numerous, and composed of a more mixed set of men, were consequently subject to a greater chance of infection, and a greater variety of complaints. The Formidable still remained healthy to an extraordinary degree. Some fevers were indeed imported from the Ville de Paris by men that had been lent to that ship, and who were taken ill after their return. Of these, a few of the worst cases were sent to the hospital, and two died on board, who, with one that died the preceding month, make the whole mortality of this ship, since leaving England, amount only to the loss of three men.

There has been little or no increase of scurvy this month; for though the numbers put on the list appear to be greater, the mortality is much less. It may indeed appear a matter of surprise that there should have been any scurvy at all, considering that the greater part of the fleet was at anchor all this month. But as this was the greatest fleet that had ever visited Jamaica, it was impossible to find fresh provisions for the whole; and the small supply they had did not amount to one fresh meal in a week. Port Royal is also remote from the cultivated part of the island, so that fruit and vegetables were both scarce and high priced, particularly this year, on account of the usual rains in May and June having failed. There was, however, an allowance of fresh provisions and vegetables made to the sick by public bounty; for as the hospital could contain but a small proportion of the sick and wounded, an order was given for the supply of fresh meat, fruit, and vegetables, to the sick, and five hundred pounds of Peruvian bark were also distributed as a public gratuity, besides sugar, coffee, and wine.

With these aids, and the various good articles of victualling from England, the fleet was preserved uncommonly healthy for a West-India campaign: for though the mortality had increased considerably during our stay at Jamaica, yet the loss of men, upon the whole, was small, compared with that of other great fleets in this climate on former occasions. The greatest squadron, next to this, that had ever been on this station was that under Admiral Vernon in the year 1741, at the same season. From this fleet upwards of eleven thousand men were sent to the hospital in the course of that and the preceding year, of whom there died one in seven, besides what died on board of their own ships and in two hospital ships17. The disproportion of sickness in the two fleets will appear still greater, when it is considered that Admiral Vernon’s contained only fifteen thousand seamen and marines18; whereas that under Lord Rodney contained twenty-two thousand. What added to the sickness of the former was the unfortunate expedition to Carthagena in April, 1741; to which probably it was owing that a much greater proportion of yellow fevers were landed from the fleet at that time than from ours, as appears by the papers left by Mr. Hume, who was then surgeon of the hospital. The hospital was then at a place called Greenwich, on the side of the bay opposite to Port Royal, and was very large; but it was found to be in a situation so extremely unhealthy, that it was soon after abandoned and demolished, and the hospital has since been at Port Royal.

It appears by the tables, that a greater number was put on the list under the head of other complaints in this month than the last. This was owing to the great number of ulcers which I have remarked to keep pace with feverish as well as scorbutic complaints; for when the constitution of the air is favourable to disease, or the habit of body prone to it, wounds and sores are found then to be more difficult of cure. There were twelve deaths besides those occasioned by what have been called the three epidemics. Of these, five perished by drowning and other accidents, three died of ulcers, one of wounds received in action, one of cholera morbus, and one of an abscess.

It has appeared that very few ships of this numerous fleet preserved their health while lying at anchor; and it would seem that short and frequent cruises are very conducive to health. It was eleven weeks from the time that the first of our fleet came to anchor at Jamaica till the main body of it sailed for America on the 17th of July. Great fleets are in time of war under the necessity of being at one time longer at sea, and at another time longer in port, than is consistent with the health of the men, the ships being obliged to act in concert and to co-operate with each other. This is one reason, among others, for ships of the line being more sickly than frigates. As ships of war must be guided by the unavoidable exigencies of service, it would be absurd to consider health only; but if this were to be the sole object of attention, a certain salutary medium could be pointed out in dividing the time between cruising and being in harbour; and it is proper that this should be known, that regard may be had to it, as far as may be consistent with the service. I would say, then, that in a cold climate men ought not to be more than six weeks at sea at one time, and need not be less than five weeks, and that a fourth part of their time spent in port would be sufficient to replenish their bodies with wholesome juices. In a warm climate men may be at sea a considerable time longer, without contracting scurvy, provided they have been under a course of fresh and vegetable diet when in port.

Though contagion is not so apt either to arise or to spread in this climate as in colder ones, there were several circumstances about this time tending to prove that it may exist in a hot climate. Those ships which had their men returned to them from the French prizes, in all of which fevers prevailed, had an increase of sickness not only in the men that were returned, but in the rest of the crew. There was another presumption of contagion, from the proportion of mortality among the surgeons and their mates, who were by their duty more exposed to the breath, effluvia, and contact of the sick. There died, during our stay at Jamaica, three of the former, and four of the latter, which is a greater proportion than what died of any other class of officers or men.

It has been the opinion of some, that fevers do not arise from any putrid effluvia, except those of the living human body, or some specific infection generated by it while under the influence of disease. It has been alledged in proof of this, that the putrid air in some great cities is breathed without any bad effects; and a celebrated professor of anatomy19 used to observe, that those employed in dissecting dead bodies did not catch acute diseases more readily than other people. I believe this may be true, in a climate like Europe, where cold invigorates the body, and enables it to resist the effects of foul air; but I am persuaded it is otherwise in tropical climates. The external heat of the air induces great languor and relaxation, and we cannot breathe the same portion of air for the same length of time in a hot as in a cold climate, without great uneasiness. The want of coolness must, therefore, be compensated by a more frequent change of air, and by its greater purity: any foulness of the air is accordingly more felt in a hot climate; and, according to the modern theory, air, already loaded with putrid phlogistic vapour, will be less qualified to absorb the same sort of vapour from the blood in the lungs, in which, according to this theory, the use of respiration consists. Be this as it will, there is something in purity of air which invigorates the circulation, and refreshes the body; and the contrary state of it depresses and debilitates, particularly in a hot climate; and in this way foul air may induce disease, like any other debilitating cause, independent of infection, or any specific quality. There was no reason to suspect any such infection in the Ville de Paris; for there was no sickness on board of this ship when in possession of the enemy, and the sickness that prevailed after her being captured seemed to proceed from what may be called simple putrefaction. There was an instance of the same kind in one of our own ships of the line, in which a bad fever broke out in the beginning of July, which seemed to be owing to the foul air of a neglected hold; for there was a putrid stench proceeding from the pumps, which pervaded the whole ship. I perceived this very sensibly one day, when visiting some officers who were ill of fevers; and before I left the ship an alarm was given of two men being suffocated in what is called the well, which is the lowest accessible part of the hold. This fever was of a very malignant kind, and fell upon the officers more than the men; for six of them were seized with it, of whom three died on the third day after being taken ill.

The fevers, which were of the greatest malignity at this time, affected the officers more than the common men. Only one captain died at Jamaica while the fleet was there, and it was of this fever. We lost five lieutenants, of whom four died of it; and this was the disease which carried off the three surgeons. But foul air was not the only cause that produced this fever among the officers, several of whom brought it on by hard drinking, or fatiguing themselves by riding or walking in the heat of the sun. It cannot be too much inculcated to those who visit tropical countries, that exercise in the sun, and intemperance, are most pernicious and fatal practices, and that it is in general by the one or the other that the better sort of people, particularly those newly arrived from Europe, shorten their lives.

Before leaving Jamaica, I sent to England a Supplement to the Memorial given in, last year20.

CHAP. V

Account of the Health of the Fleet, from its leaving Jamaica on the 17th of July, till its Departure from New York on the 25th of October. – What Diseases most prevalent on the Passage to America – Rapid Increase of the Scurvy during the last Week of the Passage – Method of supplying the Sick at New York – The Fleet uncommonly healthy in October – State of the Weather and of Health in America in Summer and Autumn, 1782.

The season of the hurricanes approaching, and all the convoys destined for England this year being dispatched, the main body of the fleet, consisting of twenty-four ships of the line, left Port Royal on the 17th of July, under the command of Admiral Pigot, in order to proceed to the coast of America. A great convoy for England had been sent off a few days before, protected by the Ville de Paris and six other ships of the line, which we overtook and passed at the west end of the island. When we arrived off the Havannah, a large squadron of the enemy was seen there in readiness to sail, which induced the Admiral to wait in sight of it for the convoy, which did not come up till ten days after. Owing to this delay, and our meeting with baffling winds on the rest of the passage, we did not arrive at New York till the 7th of September. We found there the Invincible and Warrior, which sailed after us, but arrived before us, by having taken the windward passage.

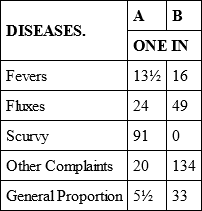

Table, shewing the proportional Prevalence of different Diseases, and their Mortality, in July, 1782Transcriber’s Keys:

A Proportion of those taken ill in the Course of the Month.

B Proportion of Deaths, in relation to the Numbers of the Sick.

The mortality this month, in relation to the whole numbers on board, was one in a hundred and thirty.

There were only one in thirty-eight of the sick sent to the hospitals.

The fevers arose chiefly during the first two weeks after leaving Jamaica, which renders it probable that the seeds of them were brought from thence. Had they been owing to the heat simply, they would have been as apt to arise in some subsequent part of the passage; for the tropical heats at this season of the year extend to the 30th degree of latitude, which we did not cross till the 22d of August, that is, near five weeks after leaving Jamaica. The only ships in which the fever could be imputed to infection or foul air were the Barfleur, Alcide, and the Aimable frigate. The first had received, as recruits, at Jamaica, men who had been confined for some time before in a French jail, and a fever of a bad kind spread on board of her soon after. The Aimable was a prize from the French; and the sickness was here so evidently owing to foul air, that, whenever the contents of the hold were stirred, so as to let loose the putrid effluvia, there was then an evident increase of sickness. The fever in the Alcide was of a peculiar slow kind, to be described hereafter, and seemed to be a continuation of the same infection which had so long existed in that ship.

The Duke, which had hitherto been by far the most subject to fevers of any ship in the fleet, became more and more free from them even in the most early part of this passage, and might be said to be entirely so at the time she arrived in America. The fever had been so very prevalent in this ship since leaving England, that there was hardly a man who had escaped it. Could this have any effect in making them less liable to catch it a second time?

In the course of this passage the dysenteries came to prevail over the fevers, as we have found to be commonly the case at sea. It appears by the former table, compared with the next, that the mortality in fevers was much the same, and that in the dysentery it was greater than while the fleet was at Jamaica. This does not argue, however, that the diseases were equally malignant, but was owing to the want of an hospital, and of those comforts of diet which the sick enjoyed on board while in harbour. This last was particularly felt in the dysenteries, in the cure of which more depends upon diet than in most other diseases. In all the calculations of mortality on board of ships, if any have been sent to the hospital, they are to be deducted from the number; and these make a greater difference in the mortality on board than their numbers simply would indicate; for only the worst cases, and those therefore who were most likely to die, used to be sent to the hospital. But as the fleet was at sea during the whole of this month, no allowance of this kind is to be made.

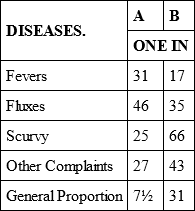

Table, shewing the proportional Sickness and Mortality in AugustTranscriber’s Keys:

A Proportion of those taken ill in the Course of the Month.

B Proportion of Deaths, in relation to the Numbers of the Sick.

The mortality this month, in relation to the whole numbers on board, was one in one hundred and sixty-nine.

The scurvy began to appear very soon upon this passage; for by the end of August, at which time the fleet had only been six weeks at sea, and that in a warm climate, and in dry weather, it had made considerable progress. It first appeared and prevailed most in the Prince George and Royal Oak, though they had been ten weeks at Jamaica. This was the first sickness with which the latter had been affected since arriving in the West Indies; and there was no perceivable peculiarity in either of them to account for their being subject to it more early, or more violently, than the rest of the fleet. If the disease is contagious, as has been suspected, there might be a few men on board of them, who, being uncommonly prone to the disease, would be soon affected, and communicate it, or at least hasten the symptoms in those who might be less predisposed to it. But this is only conjecture. Before the end of the voyage, the whole fleet was more or less afflicted with it, though it had been only seven weeks and three days at sea; but the men had received so few refreshments while in port, that their constitutions were prepared to fall into this disease. The Barfleur, Alfred, and Princessa, were most affected with it next to the two ships mentioned above.