скачать книгу бесплатно

(#litres_trial_promo) The affair was reported to Inzov, who ordered that the two should be reconciled. Two days later they both appeared before the vice-governor, Krupensky; Major-General Pushchin was also present. When they met, Balsch said, âI have been forced to apologize to you. What kind of apology do you require?â Pushkin, without a word, slapped his face and drew out a pistol, before being led from the room by Pushchin.

(#litres_trial_promo) In a letter to Inzov Balsch demanded, firstly a safeguard against any further attempt which Pushkin might make on him, and, secondly, that the other should be proceeded against with the utmost rigour of the law.

(#litres_trial_promo) Whatever the rights of the situation, there was only one choice Inzov could make between an extremely junior civil servant and a Moldavian magnate: sending Pushkin to his quarters, he placed him under house arrest for three weeks.

Arguments were frequent at Inzovâs dinner table. A few months later, on 20 July 1822, when discussing politics with Smirnov, a translator, Pushkin âbecame heated, enraged and lost his temper. Abuse of all classes flew about. Civil councillors were villains and thieves, generals for the most part swine, only peasant farmers were honourable. Pushkin particularly attacked the nobility. They all ought to be hanged, and if this were to happen, he would have pleasure in tying the noose.â

(#litres_trial_promo) When both parties were heated with wine a possible explosion was never too far away. One occurred the following day, when the conversation at dinner touched upon the subject of hailstorms; whereupon a retired army captain named Rudkovsky claimed to have once witnessed a remarkable storm, during which hailstones weighing no less than three pounds apiece had fallen. Pushkin howled with laughter, Rudkovsky became indignant, and, after they had risen from table and Inzov had left, an exchange of insults led to an agreement to exchange shots. Both, accompanied by Smirnov, who had suffered Pushkinâs abuse the previous day, then went to Pushkinâs quarters, where some kind of fracas took place. Rudkovsky asserted that Pushkin attacked him with a knife, and Smirnov, agreeing, claimed to have managed to ward off the blow. Luckily no one was injured; however, Inzov, learning of the incident, put Pushkin under house arrest again.

General Orlov, âHymenâs shaven-headed recruitâ,

(#litres_trial_promo) had married Ekaterina Raevskaya in Kiev on 15 May 1821. Pushkin welcomed her arrival in Kishinev, and would visit the couple almost every day, lounging on their divan in wide Turkish velvet trousers, and conversing with them animatedly. He went riding with Orlov and fell off. âHe can only ride Pegasus or a nag from the Don,â the general commented to his wife. âPushkin no longer pretends to be cruel,â she wrote to her brother Aleksandr in November, âhe often calls on us to smoke his pipe and discourses or chats very pleasantly. He has only just completed an ode on Napoleon, which, in my humble opinion, is very good, as far as I can judge, having heard only part of it once.â

(#litres_trial_promo) Napoleon had died on 5 May 1821 (NS); the news of his death reached Kishinev in July.

The miraculous destiny has been accomplished;

The great man is no more.

In gloomy captivity has set

The terrible age of Napoleon,

Pushkin wrote.

(#litres_trial_promo) His earlier hatred of the emperor had been replaced, if not by the hero-worship of Romanticism, at least by awe and admiration.

Orlov was a humane and enlightened commander, who was particularly anxious to reduce the incidence of corporal punishment in the units under his command. He had surrounded himself by a number of like-minded officers: Pushchin, his second-in-command, was a Decembrist, as was Okhotnikov, his aide-de-camp. So too was Vladimir Raevsky, âa man of extraordinary energy, capabilities, very well-educated and no stranger to literatureâ:

(#litres_trial_promo) a distant relative of Pushkinâs friends. Born in 1795, Raevsky had entered the army at sixteen; in 1812, as an ensign in an artillery brigade, he had been awarded a gold sword for bravery at Borodino. Now a major in the 32nd Jägers, he was the divisionâs chief education officer, responsible for all its Lancaster schools.

(#ulink_48d12b25-2783-54d1-8880-d3548192d345) This position gave him great influence on the rank-and-file of the division, and he employed it to inculcate what were considered to be dangerously subversive ideas. A later report on his activities singled out the fact that in handwriting exercises he used for examples words such as âfreedomâ, âequalityâ, and âconstitutionâ and alleged that he told officer cadets that constitutional government was better than any other form of government, and especially than Russian monarchic government, which, although called monarchic, was really despotic.

(#litres_trial_promo) A pedagogue by nature, he exposed the gaps in Pushkinâs knowledge, and was a severe critic of his verse.

In December 1821 Liprandi was ordered by Orlov to report on the condition of the 31st and 32nd Jäger regiments, stationed in Izmail and Akkerman at the mouth of the Dniester. He invited Pushkin to accompany him; Inzov, who had just been reprimanded for not keeping a strict watch over his protégé, at first refused his permission, but was persuaded by Orlov to change his mind.

Pushkin was full of historical enthusiasm when the two set off on 13 December. He was eager to stop in Bendery and visit the camp at Varnitsa, where Charles XII of Sweden had lived from 1709 to 1713, having taken refuge on Turkish territory after his defeat by Peter at Poltava â the battle which was to be the climax of, and provide the title for Pushkinâs long narrative poem of 1828â9. Liprandi, however, hurried him on. The next post-station, Kaushany, aroused his excitement again: this had been the seat, from the sixteenth century until 1806, of the khans who had ruled Budzhak, the southern region of Moldavia. But according to Liprandi there was nothing to see and, stopping only to change horses, they drove on.

They arrived in Akkerman early in the evening of the fourteenth, and went straight to dinner with Colonel Nepenin, the commander of the 32nd Jägers. Among the guests was an old St Petersburg acquaintance, Lieutenant-Colonel Pierre Courteau, now commandant of the fortress. He and Pushkin were both members of Kishinevâs short-lived Masonic lodge, Ovid, opened in the spring and closed â together with all other lodges in Bessarabia â in December by Inzov on the emperorâs orders. While Pushkin and Courteau were talking, Nepenin asked Liprandi in an undertone, audible to Pushkin, whether his friend was the author of A Dangerous Neighbour â the indecent little epic composed by Pushkinâs uncle, Vasily. Liprandi, embarrassed, and wishing to avoid further queries, replied that he was, but did not like to have it talked about. His ruse succeeded, the poem was not mentioned further; later that evening, however, Pushkin took him to task for his subterfuge, and called Nepenin an uneducated ignoramus for imagining that he, a twenty-two-year-old, could be the author of a poem which had been well-known ever since its composition ten years earlier, in 1811.

The following day, while Liprandi was inspecting the regiment, Pushkin was shown round the fortress by Courteau; they dined with him, and returned to their quarters in the early hours of the morning, after an evening spent at the card-table and in flirtation with the commandantâs âfive robust daughters, no longer in the bloom of youthâ.

(#litres_trial_promo) They left for Izmail early the following evening, arriving at ten at night and putting up with a Slovenian merchant, Slavic.

In 1791, during the Russo â Turkish war, Izmail had been stormed and captured by a Russian army commanded by Suvorov â an event celebrated by Byron in the seventh and eighth cantos of Don Juan. Pushkin was naturally impatient to inspect the scenes of the fighting: when Liprandi returned to their lodging the next evening he found that his companion had already been round the fortress with SlaviÄ; he was amazed that the besiegers had managed to scale the fortifications facing the Danube. He had also taken down a Slovenian song from the dictation of their hostâs sister-in-law, Irena. The following morning Liprandi, before leaving to inspect the 31st Jägers, introduced Pushkin to a naval lieutenant in the Danube flotilla, Ivan Gamaley; together they visited the town, the fortress and the quarantine station; were taken to the casino by SlaviÄ, and then had supper at his house with another naval lieutenant, Vasily Shcherbachev. Returning at midnight, Liprandi found Pushkin sitting cross-legged on a divan, surrounded by a large number of little pieces of paper. When asked whether he had got hold of Irenaâs curling papers, Pushkin laughed, shuffled them together and hid them under a cushion; the two emptied a decanter of local wine and went to bed. In the morning Liprandi awoke to find Pushkin, unclothed, sitting in the same posture as the previous night, again surrounded by his pieces of paper, but holding a pen in his hand with which he was beating time as he recited, nodding his head in unison. Noticing that Liprandi was awake, he stopped and gathered up his papers; he had been caught in the act of composition. That morning Liprandi, after writing his report, called on Major-General Tuchkov, who expressed the wish to meet Pushkin. He came to dinner at their lodgings and afterwards bore off Pushkin, who returned at ten in the evening, somewhat out of sorts; he wished he could stay here a month to examine properly everything the general had shown him. âHe has all the classics and extracts from them,â he told Liprandi, who jokingly suggested that he was more interested in Irenaâs classical forms.

(#litres_trial_promo)

The next morning they set out for Kishinev. Late that evening, as Pushkin was dozing in his corner of the carriage, Liprandi remarked that it was a pity it was so dark, as otherwise they could have seen to the left the site of the battle of Kagul: here in August 1770 General Rumyantsev with 17,000 men engaged the main Turkish army, winning a hard-fought battle with the bayonet and capturing the Turkish camp. Pushkin immediately started to life, animatedly discussed the battle, and quoted a few lines of verse â perhaps those from his Lycée poem, âRecollections in Tsarskoe Seloâ, in which he mentions the monument to the battle in the palace park:

In the thick shade of gloomy pines

Rises a simple monument.

O, how shameful for thee, Kagulian shore!

And glorious for our dear native land!

(#litres_trial_promo)

Arriving in Leovo before midday, they called on Lieutenant-Colonel Katasanov, the commander of the Cossack regiment stationed here. He was away, but his adjutant insisted that they should stay for lunch: caviare, smoked sturgeon â of which Pushkin was inordinately fond â and vodka appeared, succeeded by partridge soup and roast chicken. Half an hour after their departure Pushkin, who had been in a brown study, suddenly burst into such raucous and prolonged laughter that Liprandi thought he was having a fit. âI love cossacks because they are so individual and donât keep to the normal rules of taste,â he said. âWe â indeed everyone else â would have made soup from the chicken and would have roasted the partridge, but they did the opposite!â

(#litres_trial_promo) He was so struck by this that after his return to Kishinev â they arrived at nine that evening, 23 December â he sought out the French chef Tardif â âinexhaustible in ideas/For entremets, or for piesâ

(#litres_trial_promo) â then living on Gorchakovâs charity,

(#ulink_ec9d3726-2c19-510d-9222-5bd3dd1c28b6) to tell him about it, and two years later, in Odessa, reminded Liprandi of the meal.

During the winter the training battalion of the 16th division had been employed in constructing, at Orlovâs expense, a manège, or riding-school. Its ceremonial opening took place on New Yearâs Day 1822. Liprandi and Okhotnikov had decorated the interior: the walls were hung with bayonets, swords, muskets; on that opposite the entrance was a large shield, with a cannon and heap of cannon-balls to each side; in the centre was the monogram of Alexander, done in pistols, surrounded by a sunburst of ramrods, and flanked by the colours of the Kamchatka and Okhotsk regiments. Before this was a table, laid for forty guests, while eight other tables, four down each side of the hall, were to accommodate the training battalion. Inzov and his officials â including Pushkin â and the town notables were invited. The building was blessed by Archbishop Dimitry and after the ceremony all sat down to a breakfast. âThere was no lack of champagne or vodka. Some felt a buzzing in their heads, but all departed decorously.â

(#litres_trial_promo) A week later Orlov and Ekaterina left for Kiev, where they were to stay for some time. As it turned out, the absence of the divisionâs commander at this moment was unfortunate.

The 16th division was part of the 6th Corps, commanded by Lieutenant-General Sabaneev, whose headquarters were at Tiraspol, halfway between Kishinev and Odessa. Over the previous six months General Kiselev, the chief of staff of the Second Army, had stepped up surveillance of the armyâs units: he was particularly concerned about the 16th division, commanded as it was by such a noted liberal. Despite his friendship with Orlov, he had cautiously insinuated to Wittgenstein, the commander of the army, that the latter was unsuited to the command of the division. Raevsky, too, had come to his attention. âI have long had under observation a certain Raevsky, a major of the 32nd Jäger regiment, who is known to me by his completely unrestrained freethinking. At the present moment in agreement with Sabaneev an overt and covert investigation of all his actions is taking place, and he will, it seems, not escape trial and exile.â

(#litres_trial_promo)

In Orlovâs absence General Sabaneev â a short, choleric fifty-two-year-old with a red nose, ginger hair and side-whiskers â began to pay frequent visits to Kishinev. He dined with Inzov on 15 January. Pushkin was present, but was uncharacteristically silent during the meal. Sabaneev was in Kishinev again on the twentieth, when he wrote to Kiselev: âThere is no one in the Kishinev gang besides those whom you know about, but what aim this gang has I do not as yet know. That well-known puppy Pushkin cries me up all over town as one of the Carbonari, and proclaims me guilty of every disorder. Of course, it is not unintentional, and I suspect him of being an organ of the gang.â

(#litres_trial_promo)

On 5 February, at nine in the evening, Raevsky was reclining on his divan and smoking a pipe when there was a knock on the door; his Albanian servant let in Pushkin. He had, he told Raevsky, just eavesdropped on a conversation between Inzov and Sabaneev. Raevsky was to be arrested in the morning. âTo arrest a staff officer on suspicion alone has the whiff of a Turkish punishment. However, what will be, will be,â Raevsky remarked. Lost in admiration at his coolness, Pushkin attempted to embrace him. âYouâre no Greek girl,â said Raevsky, pushing him away. The two went round to Liprandi, who was entertaining a number of guests, including his younger brother, Pavel, Sabaneevâs adjutant. When Raevsky and Pushkin entered, they were assailed with questions as to what was going on. âAsk Pavel Petrovich,â Raevsky replied, âhe is Sabaneevâs trusted plenipotentiary minister.â âTrue,â said the younger Liprandi, âbut if Sabaneev trusted you as he trusts me, you too would not wish to break the codes of trust and honour.â

(#litres_trial_promo) At noon the next day he was summoned to Sabaneev, and confronted with three officer cadets, members of his Lancaster school, whose testimony as to his teaching was the ostensible reason for his arrest. His books and papers were confiscated and a guard put on his quarters. A week later he was taken to Tiraspol and lodged in a cell in the fortress. The investigation into his case and his trial dragged on for years. Only in 1827 was he finally sentenced to exile in Siberia. In March Major-General Pushchin was relieved of his command of a brigade in Orlovâs division, and the following April Kiselev succeeded in bringing about Orlovâs removal from his command.

In July 1822 Liprandi, passing through Tiraspol on his way from Odessa to Kishinev, managed, with the connivance of the commandant of the fortress, to have half an hourâs conversation with Raevsky as they strolled backwards and forwards over the glacis. Raevsky gave him a poem, âThe Bard in the Dungeonâ, to pass on to Pushkin, who was particularly impressed by one stanza:

Like an automaton, the dumb nation

Sleeps in secret fear beneath the yoke:

Over it a bloody clan of scourges

Both thoughts and looks executes on the block.

Reading it aloud to Liprandi, he repeated the last line, and added with a sigh: âAfter such verses we will not see this Spartan again soon.â

(#litres_trial_promo)

Although the authorities knew that Raevsky was a member of some kind of conspiracy, he remained resolutely silent in prison, and no other arrest followed his. Pushkin was surprised and shocked by the incident, which in addition appeared to him deeply mysterious: the severity of Raevskyâs treatment seemed wholly out of proportion to his crime. It was only in January 1825, when his old Lycée friend Pushchin visited him in Mikhailovskoe, that he gained some inkling of what had been going on. âImperceptibly we again came to touch on his suspicions concerning the society,â writes Pushchin. âWhen I told him that I was far from alone in joining this new service to the fatherland, he leapt from his chair and shouted: âThis must all be connected with Major Raevsky, who has been sitting in the fort at Tiraspol for four years and whom they cannot get anything out of.ââ

(#litres_trial_promo)

In December 1820 Pushkin had written from Kamenka to Gnedich, the publisher of Ruslan and Lyudmila, to tell him that his next narrative poem, The Prisoner of the Caucasus, was nearly completed. He was unduly optimistic; it was not until the following March that he wrote again. âThe setting of my poem should have been the banks of the noisy Terek, on the frontier of Georgia, in the remote valleys of the Caucasus â I placed my hero in the monotonous plains where I myself spent two months â where far distant from one another four mountains rise, the last spur of the Caucasus; â there are no more than 700 lines in the whole poem â I will send it you soon â so that you might do with it what you like.â

(#litres_trial_promo) Before long, however, he was having second thoughts; he was in need of money and, compared to Gnedich, had made little out of Ruslan. In September he wrote to Grech, editor of Son of the Fatherland. âI wanted to send you an extract from my Caucasian Prisoner, but am too lazy to copy it out; would you like to buy the poem from me in one piece? It is 800 lines long; each line is four feet wide; it is chopped into two cantos. I am letting it go cheaply, so that the goods do not get stale.â

(#litres_trial_promo) Unfortunately, Gnedich got wind of the offer. âYou tell me that Gnedich is angry with me,â he wrote to his brother in January 1822, âhe is right â I should have gone to him with my new narrative poem â but my head was spinning â I had not heard from him for a long time; I had to write to Grech â and using this dependable occasion

(#ulink_069deb3a-022c-5d8b-a6a9-212c53ee1ca9) I offered him the Captive ⦠Besides, Gnedich will not haggle with me, nor I with Gnedich, each of us over-concerned with his own advantage, whereas I would have haggled as shamelessly with Grech as with any other bearded connoisseur of the literary imagination.â

(#litres_trial_promo) He also made an attempt to sell the poem directly to book-sellers in St Petersburg, but, offered a derisory sum, had to fall back on Gnedich. On 29 April he sent him the manuscript, accompanying it with a letter which began âParve (nec invideo) sine me, liber, ibis in urbem,/Heu mihi! quo domino non licet ireâ â the opening lines of Ovidâs Tristia,

(#ulink_1e3c8789-d640-5ee0-86d5-97637b965e2a) â and continued: âExalted poet, enlightened connoisseur of poets, I hand over to you my Caucasian prisoner [â¦] Call this work a fable, a story, a poem or call it nothing at all, publish it in two cantos or in only one, with a preface or without; I put it completely at your disposal.â

(#litres_trial_promo)

Pushkinâs friends knew that he had been at work on a successor to Ruslan: âPushkin has written another long poem, The Prisoner of the Caucasus,â Turgenev had told Dmitriev the previous May; âbut he has not mended his behaviour: he is determined to resemble Byron not in talent alone.â

(#litres_trial_promo) When the manuscript arrived in St Petersburg, it was bitterly fought over. âI have not set eyes on the Caucasian captive,â Zhukovsky complained to Gnedich at the end of May; âTurgenev, who has no interest in reading himself, but only in taking other peopleâs verse around on visits, has decided not to send me the poem, since he is afraid of letting it out of his claws, lest I (and not he) should show it to someone. I beg you to let me have it as soon as possible; I will not keep it for more than a day and will return it immediately.â

(#litres_trial_promo) Turgenev eventually did take the poem out to Zhukovsky in Pavlovsk, but Vyazemsky, who had been clamouring for it â âThe Captive, for Godâs sake, just for one post,â he implored Turgenev

(#litres_trial_promo) â had to wait until publication.

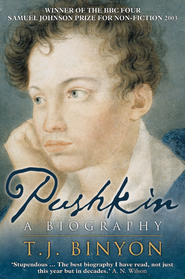

The Prisoner of the Caucasus came out on 14 August â a small book of fifty-three pages, costing five roubles, or seven if on vellum. A note at the end of the poem read: âThe editors have added a portrait of the author, drawn from him in youth. They believe that it is pleasing to preserve the youthful features of a poet whose first works are marked by so unusual a talent.â

(#litres_trial_promo) The portrait, engraved by Geitman, depicts Pushkin âat fifteen, as a Lycéen, in a shirt, as Byron was then drawn, with his chin on his hand, in meditationâ.

(#litres_trial_promo) Gnedich, more expeditious than before, sent him a single copy of the poem in September, together with a copy of Zhukovskyâs translation of Byronâs The Prisoner of Chillon. Pushkin wrote to him on 27 September: âThe Prisoners have arrived â and I thank you cordially, dear Nikolay Ivanovich [â¦] Aleksandr Pushkin is lithographed in masterly fashion, but I do not know whether it is like him, the editorsâ note is very flattering, but I do not know whether it is just.â

(#litres_trial_promo) The edition â probably of 1,200 copies â sold out with remarkable speed: in 1825 Pletnev, searching for a copy to send to Pushkin in Mikhailovskoe, could not find one. Of the profit Gnedich sent Pushkin 500 roubles, keeping, it has been calculated, 5,000 for himself.

(#litres_trial_promo) This time he had been too sharp. The following August Pushkin wrote to Vyazemsky; âGnedich wants to buy a second edition of Ruslan and The Prisoner of the Caucasus from me â but timeo danaos,* i.e., I am afraid lest he should treat me as before.â

(#litres_trial_promo) Gnedich did not get the rights: The Prisoner was the last of Pushkinâs works he published.

Its plot is not difficult to recapitulate: a Russian journeying in the Caucasus is captured by a Circassian tribe; a young girl falls in love with the captive, but he cannot return her feeling. Nevertheless, she aids him to escape: he swims the river and reaches the Russian lines; she drowns herself. In a letter to Lev describing his journey through the Caucasus Pushkin had toyed with the fancy of a Russian general falling prey to a Circassianâs lasso. The fancy becomes real in the poemâs opening lines; but the plot might also owe something to Chateaubriandâs Atala (1801), in which an American Indian, made prisoner by another tribe and about to be burnt at the stake, is freed by a native girl, with whom he flees; she later commits suicide. The poemâs hero is a Byronic figure, and the poem itself resembles Byronâs eastern poems, The Bride of Abydos, The Giaour and particularly The Corsair. Pushkin, however, undercuts Romantic ideology with an ironic paradox: fleeing the corruption and deceit of society to search for freedom in a wild and exotic region peopled by man in his natural state, the hero becomes a prisoner of the mountain tribesmen who incarnate his ideal. There is, too, a peculiar ideological discrepancy between the poem and its epilogue, written in Odessa in May 1821. This preaches an imperial message, celebrating the pacification of the Caucasus, and praising the Russian generals who forcibly subdued the tribes. Vyazemsky was shocked. âIt is a pity that Pushkin should have bloodied the final lines of his story,â he wrote to Turgenev. âWhat kind of heroes are Kotlyarevsky and Ermolov? What is good in the fact that he âlike a black plague,/Destroyed, annihilated the tribesâ? Such fame causes oneâs blood to freeze in oneâs veins, and oneâs hair to stand on end. If we had educated the tribes, then there would be something to sing. Poetry is not the ally of executioners; they may be necessary in politics, and then it is for the judgement of history to decide whether it was justified or not; but the hymns of a poet should never be eulogies of butchery. I am annoyed with Pushkin, such enthusiasm is a real anachronism.â

(#litres_trial_promo)

Anachronistic or not, these were definitely Pushkinâs views. âThe Caucasian region, the sultry frontier of Asia, is curious in every respect,â he had written in 1820. âErmolov has filled it with his name and beneficent genius. The savage Circassians have become frightened; their ancient audacity is disappearing. The roads are becoming safer by the hour, and the numerous convoys are superfluous. One must hope that this conquered region, which up to now has brought no real good to Russia, will soon through safe trading bring us close to the Persians, and in future wars will not be an obstacle to us â and, perhaps, Napoleonâs chimerical plan for the conquest of India will come true for us.â

(#litres_trial_promo) He obviously could see no contradiction between his fiery support of Greek independence and his equally fiery desire to eradicate Caucasian independence; nor between his whole-hearted support of the government here and his equally whole-hearted denunciation of the government everywhere else. In fact, some of the Decembrists shared his view that the Caucasus could not be independent: Pestel, in his Russian Justice, writes that some neighbouring lands âmust be united to Russia for the firm establishment of state securityâ, and names among them: âthose lands of the Caucasian mountain peoples, not subject to Russia, which lie to the north of the Persian and Turkish frontiers, including the western littoral of the Caucasus, presently belonging to Turkeyâ.

(#litres_trial_promo) They did not, however, share his chimerical Indian plan, nor the pleasure â the real stumbling-block for Vyazemsky â which he apparently took in genocide.

âTell me, my dear, is my Prisoner making a sensation?â he asked his brother in October 1822. âHas it produced a scandal, Orlov writes, that is the essential. I hope the critics will not leave the Prisonerâs character in peace, he was created for them, my dear fellow.â

(#litres_trial_promo) He was to be disappointed: there was no critical polemic over the poem, as there had been over Ruslan and Lyudmila. The Byronic poem had ceased to be a novelty; Pushkinâs reputation was now more firmly established, and, above all, The Prisoner did not have that awkward contrast between present-day narrator and past narrative which had worried some critics, nor that equally awkward comic intent, which had worried others. Praise was almost unanimous. In September Pushkinâs uncle wrote to Vyazemsky: âHere is what our La Fontaine [Dmitriev] writes to our Livy [Karamzin]: âYesterday I read in one breath The Prisoner of the Caucasus and from the bottom of my heart wished the young poet a long life! What a prospect! Right at the beginning two proper narrative poems, and what sweetness in the verse! Everything is picturesque, full of feeling and wit!â I confess, that reading this letter, I shed a tear of joy.â

(#litres_trial_promo) Karamzin was slightly less enthusiastic. âIn the poem of that liberal Pushkin The Prisoner of the Caucasus the style is picturesque: I am dissatisfied only with the love intrigue. He really has a splendid talent: what a pity that there is no order and peace in his soul and not the slightest sense in his head.â

(#litres_trial_promo) Of the critics only Mikhail Pogodin, in the Herald of Europe, descended to the kind of pedantic quibbling that had characterized reviews of Ruslan. Of the lines âNeath his wet burka, in the smoky hut/The traveller enjoys peaceful sleepâ (I, 321â2), he remarks: âHe would be better advised to throw off his wet burka [a felt cloak, worn in the Caucasus], and dry himself.â

(#litres_trial_promo) Pushkinâs comment, when meditating corrections for a second edition, was: âA burka is waterproof and gets wet only on the surface, therefore one can sleep under it when one has nothing better to cover oneself with.â

(#litres_trial_promo)

Where dissatisfaction was felt, it was, as in Karamzinâs case, with the love intrigue: the character of the hero, and the fate of the heroine. In the second edition of 1828 Pushkin inserted a note: âThe author also agrees with the general opinion of the critics, who justifiably condemned the character of the prisonerâ;

(#litres_trial_promo) and in 1830 wrote: âThe Prisoner of the Caucasus is the first, unsuccessful attempt at character, which I had difficulty in managing; it was received better than anything I had written, thanks to some elegiac and descriptive verses. But on the other hand Nikolay and Aleksandr Raevsky and I had a good laugh over it.â

(#litres_trial_promo) âThe character of the Prisoner is not a success; this proves that I am not cut out to be the hero of a Romantic poem. In him I wanted to portray that indifference to life and its pleasures, that premature senility of soul, which have become characteristic traits of nineteenth-century youth,â he wrote to Gorchakov.

(#litres_trial_promo) Criticism of the fate of the Circassian maiden, however, he met with some irony: to Vyazemsky, after thanking him for his review

(#ulink_393b62fa-5ede-55c7-b143-577eb1e9df10) â âYou cannot imagine how pleasant it is to read the opinion of an intelligent person about oneselfâ â he wrote: â[Chaadaev] gave me a dressing-down for the prisoner, he finds him insufficiently blasé; unfortunately Chaadaev is a connoisseur in that respect [â¦] Others are annoyed that the Prisoner did not throw himself into the water to pull out my Circassian girl â yes, you try; I have swum in Caucasian rivers, â youâll drown yourself before you find anything; my prisoner is an intelligent man, sensible, not in love with the Circassian girl â he is right not to drown himself.â

(#litres_trial_promo)

âIn general I am very dissatisfied with my poem and consider it far inferior to Ruslan,â he told Gorchakov.

(#litres_trial_promo) He was right: The Prisoner has none of the wit, the gaiety and the grace of the earlier poem; he was not âcut out to be the hero of a Romantic poemâ. But a combination of circumstances â his reading of Byron, his acquaintance with Aleksandr Raevsky, his exile â had led him down a blind alley: it was still to take him some time to retrace his steps fully. A significant move in this direction took place when, on 9 May 1823, he began Eugene Onegin. At the head of the first stanza in the manuscript this date is noted with a large, portentously shaped and heavily inked numeral. It was a significant, indeed fatidic date in Pushkinâs life: on 9 May 1820, according to his calendar, his exile from St Petersburg had begun. He usually worked on the poem in the early morning, before getting up. Visitors found him, as Liprandi had glimpsed him in Izmail, sitting cross-legged on his bed, surrounded by scraps of papers, ânow meditative, now bursting with laughter over a stanzaâ.

(#litres_trial_promo) âAt my leisure I am writing a new poem, Eugene Onegin, in which I am transported by bile,â he told Turgenev some months later.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Meanwhile changes in the regionâs administration were taking place. On 7 May 1823 Alexander signed an order freeing Inzov from his duties and appointing Count Mikhail Vorontsov governor-general of New Russia and of Bessarabia. Informing Vyazemsky of this, Turgenev wrote: âI do not yet know whether the Arabian devil* will be transferred to him. He was, it seems, appointed to Inzov personally.â âHave you spoken to Vorontsov about Pushkin?â Vyazemsky asked. âIt is absolutely necessary that he should take him on. Petition him, good people! All the more as Pushkin really does want to settle down, and boredom and vexation are bad counsellors.â Turgenevâs agitation was successful. âThis is what happened about Pushkin. Knowing politics and fearing the powerful of this world, consequently Vorontsov as well, I did not want to speak to him, but said to Nesselrode under the guise of doubt, whom should he be with: Vorontsov or Inzov. Count Nesselrode affirmed the former, and I advised him to tell Vorontsov of this. No sooner said than done. Afterwards I myself spoke twice with Vorontsov, explained Pushkin to him and what was necessary for his salvation. All, it seems, should go well. A Maecenas, the climate, the sea, historical reminiscences â there is everything; there is no lack of talent, as long as he does not choke to death.â

(#litres_trial_promo)

Unaware of these machinations, Pushkin had successfully requested permission to spend some time in Odessa: the excuse being that he needed to take sea baths for his health. He arrived at the beginning of July and put up at the Hotel du Nord on Italyanskaya Street. âI left my Moldavia and appeared in Europe â the restaurants and Italian opera reminded me of old times and by God refreshed my soulâ. Vorontsov and his suite arrived on the evening of 21 July. The following day Vorontsov summoned him to his presence. âHe receives me very affably, declares to me that I am being transferred to his command, that I will remain in Odessa â this seems fine to me â but a new sadness wrung my bosom â I began to regret my abandoned chains.â

(#ulink_a56531d0-5f3a-5104-8fb3-225cb6d38e0d) On the twenty-fourth a large ball was given in honour of Vorontsov by the Odessa Chamber of Commerce; on the twenty-sixth Vorontsov and his suite, now including Pushkin, left for Kishinev, where, two days later, Inzov handed over his post to his successor. Pushkin had time to collect his salary before accompanying the new governor-general back to Odessa at the beginning of August. âI travelled to Kishinev for a few days, spent them in indescribably elegiac fashion â and, having left there for good, sighed after Kishinev.â

(#litres_trial_promo)

* (#ulink_b439d54c-cc30-5033-bf8f-5a87086de8c2) Written in November 1820 and published the following year, âThe Black Shawlâ, in which a jealous lover kills his Greek mistress and her Armenian paramour, became, though an indifferent work, one of Pushkinâs most popular poems. It was set to music by the composer Aleksey Verstovsky in 1824, and often performed.

* (#ulink_c2bc2b7d-08b9-532b-9405-5889db54a1cc) It is thought that Pushkin might have paid a second visit to Kamenka, Kiev, and possibly Tulchin in November-December 1822, but there is no direct evidence as to his whereabouts at this time. The arguments supporting the hypothesis are summarized in Letopis, I, 504â5.

â (#ulink_c2bc2b7d-08b9-532b-9405-5889db54a1cc) From the Phanari, or lighthouse quarter of Constantinople, which became the Greek quarter after the Turkish conquest: and hence the appellation of the Greek official class under the Turks, through whom the affairs of the Christian population in the Ottoman empire were largely administered.

* (#ulink_fad9ec97-c976-55d2-86ef-58f3fa18273c) A slip of the pen: there were approximately 25,000 Turks in the Morea.

* (#ulink_04787cc1-719d-5a36-8226-3d14e02a52a3) Pushkin could later, when in Moscow in 1826â7, have met a woman who had indubitably been Byronâs mistress: Claire Clairmont, the mother of Byronâs daughter Allegra, was employed as a governess in Moscow from 1825 to 1827, first by the Posnikov, and later by the Kaisarov family. She met Pushkinâs uncle, Vasily, and his close friend, Sobolevsky, but Pushkin himself was apparently unaware of her existence.