Полная версия:

Pushkin

PUSHKIN

A Biography

T. J. BINYON

DEDICATION

For Helen

and In memory of my father Denis Binyon

EPIGRAPH

What business is it of the critic or reader whether I am handsome or ugly, come from an ancient nobility or am not of gentle birth, whether I am good or wicked, crawl at the feet of the mighty or do not even exchange bows with them, whether I gamble at cards and so on. My future biographer, if God sends me a biographer, will concern himself with this.

PUSHKIN, 1830

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

Family Trees

Maps

Prologue

1 Ancestry and Childhood, 1799â1811

2 The Lycée, 1811â17

3 St Petersburg, 1817â20: I Literature and

4 St Petersburg, 1817â20: II Oneginâs Day

5 St Petersburg, 1817â20: III Triumph

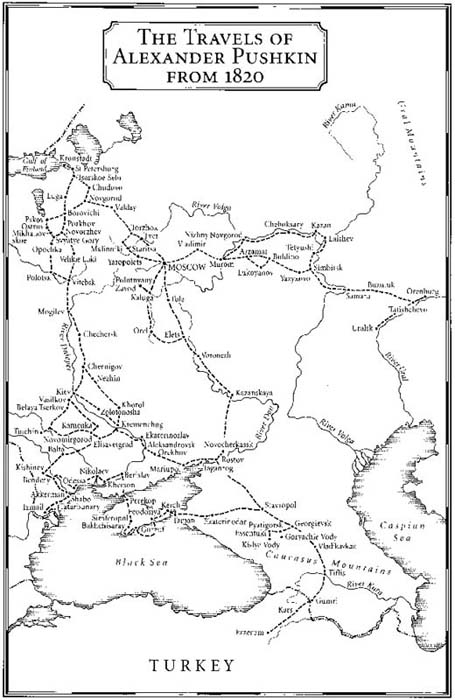

6 The Caucasus and Crimea, 1820

7 Kishinev, 1820â23

8 Odessa, 1823â24

9 Mikhailovskoe, 1824â26

10 In Search of a Wife, 1826â29

11 Courtship, 1828â31

12 Married Life, 1831â33

13 The Tired Slave, 1833â34

14 A Sea of Troubles, 1834â36

15 The Final Chapter, 1836â37

Epilogue

List of Abbreviations

Bibliography

Index

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Notes

A Note on Translation, Transliteration, Dates, Currency and Ranks

Praise

Other Works

Copyright

About the Publisher

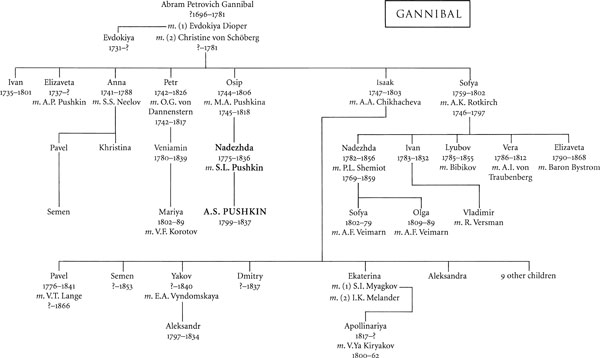

FAMILY TREES

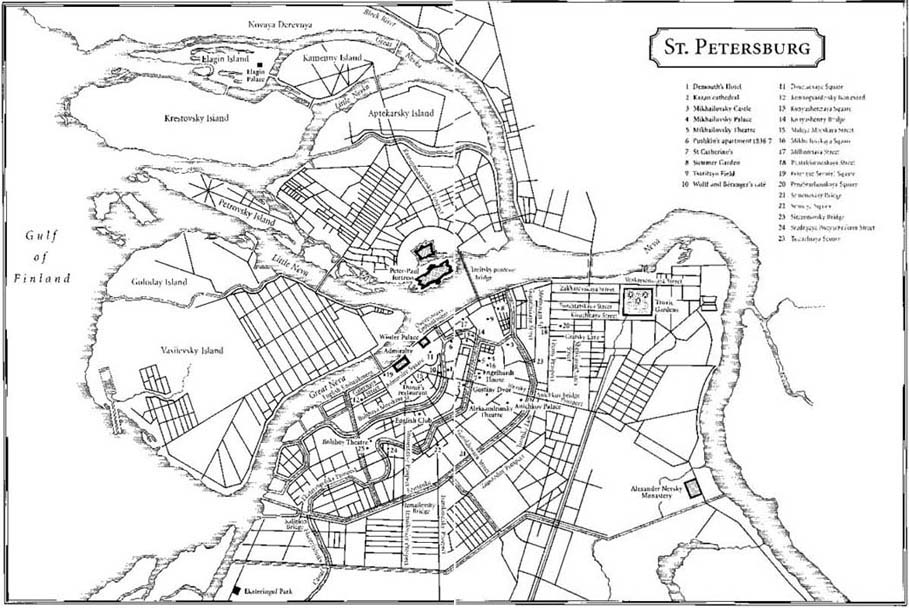

MAPS

PROLOGUE

By now it is not so much Pushkin, our national poet, as our relationship to Pushkin that has become as it were our national characteristic.

ANDREY BITOV, 1986

âPUSHKIN IS OUR ALL,â declared the critic and poet Apollon Grigorev in 1854.1 His famous remark is perhaps the best expression of Pushkinâs significance, not merely for Russian literature, or even for Russian culture, but for the Russian ethos generally and for Russia as a whole. At the time, however, his was a lone voice. Though Pushkin had been acclaimed as Russiaâs greatest poet during his lifetime, his reputation had begun to sink during his last years. The decline continued after his death in 1837, reaching perhaps its lowest point in the 1850s. In 1855 a petition, noting that monuments to a number of other writers â Lomonosov, Derzhavin, Koltsov, Karamzin and Krylov â had been erected, called for Pushkin to be added to their number. It met with no response. In 1861 Pushkinâs school, the Lycée â which had moved from Tsarskoe Selo to St Petersburg and been renamed the Alexandrine Lycée â celebrated its fiftieth anniversary. In conjunction with this a public subscription was opened to erect a statue to Pushkin in Tsarskoe Selo. Three years later less than a fifth of the necessary sum had been subscribed, and interest in the project had lapsed completely. However, by 1869, when the idea was revived by a group of former lycéens, Pushkinâs reputation was on the rise. This time the subscription was successful, raising over 100,000 roubles. The suggestion of Admiral Matyushkin, a schoolfellow of Pushkin, that the monument should be placed in Moscow, the poetâs native city, was accepted, and a site on Strastnaya Square, at the end of Tverskoy Boulevard, was chosen. After three competitions A.M. Opekushinâs design for a statue showing a meditating Pushkin emerged as the winner.

Only after eleven years of procrastination and preparation, however, was the project completed. The unveiling ceremony was planned for 26 May 1880, the eighty-first anniversary of Pushkinâs birth, but the death of Empress Mariya caused it to be postponed until Friday 6 June. At one oâclock that day, after a service in the Strastnoy monastery opposite the site of the monument, the statue was unveiled in the presence of an immense crowd. Cheers rang out, and many wept. âWhere are the colours, where are the words to convey the intoxication of the triumphal moment?â wrote one reporter. âThose who didnât see it did not see the populace in one of its best moments of spiritual joyousness.â2 That evening a banquet, given by the city duma, was followed by a literary-musical evening in the hall of the Noble Assembly. Overtures from operas based on Pushkinâs works were performed; congratulatory telegrams from Tennyson, Victor Hugo and others were read out; Dostoevsky, Turgenev and others gave readings from Pushkin: Turgenev especially being greeted with tumultuous applause.

The next day, 7 June, at a public meeting of the Society of Amateurs of Russian Literature, Turgenev gave an elegant and civilized speech. Pushkin was, he said, repeating Belinsky, Russiaâs âfirst artist-poetâ. âThere is no doubt,â he continued, âthat he created our poetic, our literary language and that we and our descendants can only follow the path laid down by his genius.â But in the end he had reluctantly to deny Pushkin the title of âa national poet in the sense of a universal poetâ, as were Shakespeare, Goethe or Homer. Unlike them, he had had to perform two tasks simultaneously, âto establish a language and create a literatureâ. And, unlike them, he had had the misfortune to die young, without fulfilling his true potential. Turgenev ended his speech by apostrophizing the statue itself. âShine forth, like him, thou noble bronze visage, erected in the very heart of our ancient capital, and announce to future generations our right to call ourselves a great nation, because this nation has given birth, among other great men, to such a man!â, a peroration which was greeted with enthusiasm and loud applause.3

Its reception, however, was completely overshadowed by that given to Dostoevskyâs long, passionate and emotional address the following morning, the third and last day of the celebrations. He began by quoting Gogolâs remark that Pushkin was âan extraordinary, and perhaps unique manifestation of the Russian spiritâ, and added that he was, too, âa prophetic oneâ. Whereas Turgenev had been unable to rank Pushkin with poets such as Shakespeare, Dostoevsky proclaimed his superiority to the âShakespeares, Cervanteses and Schillersâ, because of âsomething almost even miraculousâ, his âuniversal responsivenessâ, a characteristic which he shared with the Russian people. Whereas Shakespeareâs Italians are disguised Englishmen, Pushkinâs Spaniards are Spanish, his Germans German and his Englishmen English. âI can positively say that there has never been a poet with so universal a responsiveness as Pushkin, and it is not just his responsiveness, but its astounding depth, the reincarnation of his spirit in the spirit of foreign peoples, an almost complete, and hence miraculous reincarnation, because nowhere, in no poet of the entire world has this phenomenon been repeated.â It is this national characteristic which will eventually enable Russia to save Europe and âto pronounce the final word of great, general harmony, of the final brotherly agreement of all nations in accordance with the law of Christâs Gospel!â If this seems a presumptuous claim for a land as poor as Russia, âwe can already point to Pushkin, to the universality and panhumanity of his genius [â¦] In art at least, in artistic creation, he undeniably manifested this universality of the aspiration of the Russian spirit.â Had Pushkin lived longer his message would perhaps have been clearer. âBut God decreed otherwise. Pushkin died in the full development of his powers, and undoubtedly carried to his grave a certain great mystery,â Dostoevsky concluded. âAnd now we must solve this mystery without him.â4

Screams and cries were heard from the audience. A number of people fainted; a student burst through the throng and fell in hysterics at Dostoevskyâs feet where he lost consciousness. At the end of the session a hundred young women, pushing Turgenev aside, made their way on to the stage bearing a huge laurel wreath, nearly five feet in diameter, and placed it round the authorâs neck. It bore the inscription âFor the Russian woman, about whom you said so much that was good!â Late that evening Dostoevsky took a cab to Tverskaya Square, placed the wreath at the foot of the granite pedestal on which the statue stood, and, stepping back a pace, bowed to the ground.5

Dostoevskyâs speech had little to do with the reality of Pushkinâs work: he had, rather, unscrupulously made use of the otherâs reputation to propagate his own belief in Russiaâs messianic mission. However, it came as a fitting conclusion to what one newspaper referred to as âdays of a magically poetic fairy-taleâ, and others as âdays of holy ecstasyâ and âthe âholy weekâ of the Russian intelligentsiaâ. Some witnesses experienced something akin to a religious conversion, one reporter writing, âIt was as if the atmosphere surrounding the celebration caught fire and was lit by an iridescent radiance. Oneâs heart beat faster, more joyfully, oneâs thoughts became bright and lucid, and oneâs whole being opened up to impressions and emotions that would have been incomprehensible and strange given other less elevating circumstances. Some kind of moral miracle took place, a moral shock that stirred oneâs innermost soul.â6 But it also established a new attitude to Pushkin: from now on he was not merely a poet superior to all others, but also was no longer a man; he had become a symbol, a myth, an icon.

By 1899, the hundredth anniversary of his birth, the state had taken account of the potency of the poetâs image, and organized for the occasion an immense celebration throughout the Russian empire. Busts and portraits were mass-produced, and schoolchildren given free copies of his works, together with bars of chocolate stamped with his picture. The Pushkin of 1899 was far removed from the prophetic, miraculously responsive Pushkin of 1880; he was a solid, upright, moral citizen, a firm patriot and a loyal supporter of autocracy. In 1937 the Soviet state launched an even more massive celebration of the hundredth anniversary of Pushkinâs death. His works were recruited to assist the drive towards universal literacy in the Soviet Union, while his image was tailored to fit Soviet ideology. âPushkin is completely ours, Soviet, for the Soviet state inherited everything that is best in our people, and itself is the embodiment of the best aspirations of our people,â wrote Pravda.7 The myth had now become the basis for a cult â at times uncomfortably close to the Stalin cult â and Pushkin himself a quasi-divine figure, not only âcreator of the Russian literary language, father of new Russian literature, a genius who enriched humanity with his worksâ,8 but also a proto-Marxist who espoused the cause of liberty and of the common people; a man who gilded everything he touched and was without fault in every aspect of his life. Most recently, the celebrations of 1999 have enlisted Pushkin in the service of capitalism and commercial enterprise. The Bank of Russia brought out a number of commemorative silver and gold coins; the twenty-five-rouble silver has on its reverse âa picture of A.S. Pushkin holding a writing book and a goose-quill in his hands, in the background to the right â personages of his works of literatureâ.9 His portrait was to be seen in shop windows, on the sides of buses and trams, on billboards, boxes of matches, vodka bottles and T-shirts, while Coca-Cola ran an advertisement featuring lines from his most famous love lyric, âI recollect a wondrous momentâ. And the Foreign Minister, Igor Ivanov, when condemning in language reminiscent of the Cold War western intervention in Yugoslavia, added that NATO had foolishly ignored Pushkinâs lessons on the Balkans â thus preserving the poetâs reputation, acquired in the Soviet era, for being a genius in every sphere.*

Of course, in one sense the myth is justified: Pushkin is Russiaâs greatest poet, the composer of a large body of magnificent lyrics, extraordinarily diverse both in theme and treatment; of a number of great narrative poems â Ruslan and Lyudmila, The Gypsies, Poltava and The Bronze Horseman â and of a unique novel in verse, Eugene Onegin. He reformed Russian poetic language: in his hands it became a powerful, yet flexible instrument, with a diapason stretching from the solemnly archaic to the cadences of everyday speech. The aim of this biography, however, is, in all humility, to free the complex and interesting figure of Pushkin the man from the heroic simplicity of Pushkin the myth. It concerns itself above all with the events of his life: though the appearance of his main works is noted, and the works themselves are commented on briefly, literary analysis has been eschewed, as being the province of the critic, rather than the biographer.

* He is presumably referring to Pushkinâs remarks on the Polish revolt of 1830, particularly the poem âTo the Slanderers of Russiaâ.

1 ANCESTRY AND CHILDHOOD 1799â1811

Lack of respect for oneâs ancestors is the first sign of barbarism and immorality.

VIII, 42

A LEKSANDR PUSHKIN was born in Moscow on Thursday 26 May 1799, in a âhalf-brick and half-wooden houseâ on a plot of land situated on the corner of Malaya Pochtovaya Street and Gospitalny Lane.1 This was in the eastern suburb known as the German Settlement, to which foreigners had been banished in 1652. Though distant from the centre, it was, up to the fire of 1812, a fashionable area, âthe faubourg Saint-Germain of Moscowâ.2 On 8 June he was baptized in the parish church, the Church of the Epiphany on Elokhovskaya Square.* And that autumn his parents, Sergey and Nadezhda, took him and his sister Olga â born in December 1797 â to visit their grandfather Osip Gannibal, Nadezhdaâs father, on his estate at Mikhailovskoe, in the Pskov region. Most of the next year was spent in St Petersburg. The Emperor Paul, coming across Pushkin and his nurse, reprimanded the latter for not removing the babyâs cap in the presence of royalty, and proceeded to do so himself. In the autumn they moved back to Moscow, where they were to remain for the duration of Pushkinâs childhood.

Pushkin was proud of both sides of his ancestry: both of his fatherâs family, the Pushkins, and of his motherâs, the Gannibals. However, the two were so different from one another, antipodes in almost every respect, that to take equal pride in both required the reconciliation of contradictory values. In Pushkin the contradictions were never completely resolved, and the resulting tension would occasionally manifest itself, both in his behaviour and in his work. The most obvious difference lay in the origins of the two families: whereas the Pushkins could hardly have been more Russian, the Gannibals could hardly have been more exotic and more foreign.

On 15 November 1704 an official at the Foreign Office in Moscow passed on to General-Admiral Golovin, the minister, news of a Serbian trader who was employed by the department. âBefore leaving Constantinople on 21 June,â he wrote, âMaster Savva Raguzinsky informed me that according to the order of your excellency he had acquired with great fear and danger to his life from the Turks two little blackamoors and a third for Ambassador Petr Andreevich [Tolstoy], and that he had sent these blackamoors with a man of his for safety by way of land through the Walachian territories.â3 The boys had just arrived, the writer added; he had dispatched one to the ambassadorâs home, and the other two, who were brothers, to the Golovin palace. The younger of these was in the course of time to become General Abram Petrovich Gannibal, cavalier of the orders of St Anne and Alexander Nevsky: Pushkinâs maternal great-grandfather.*

Golovin had acquired the two boys as a gift for the tsar, to whom they were presented when he came to Moscow in December 1704. Peter had the elder brother baptized in the Preobrazhensky parish in Moscow, when he was given the name Aleksey, and the patronymic Petrov, from the tsarâs own name. He was trained as a musician and attached to the Preobrazhensky regiment, where he played the hautboy in the regimental band. Unlike his younger brother Abram, he then vanishes from the pages of history.

Abram was from the beginning a favourite of the tsar. On 18 February 1705 the account-book of the royal household notes: âto Abram the negro for a coat and trimming were given 15 roubles 45 copecksâ.4 In the spring of 1707 Peter began a campaign against the Swedes. That autumn he celebrated a victory over Charles XII in the Orthodox Pyatnitskaya church in Vilna and simultaneously had his new protégé baptized, acting as his godfather and giving him, like his brother, the patronymic Petrov. And a document of 1709 notes that âby the tsarâs order caftans have been made for Joachim the dwarf and Abram the blackamoor, for the Christmas festival, with camisoles and breechesâ.5

In 1716 Peter made a second journey to Europe. Abram was one of his retinue, and was left in France together with three other young Russians to study fortification, sapping and mining at a military school. They returned to Russia in 1723, when Abram was commissioned as a lieutenant and posted to Riga. Peter died in February 1725, but his wife, Catherine, who succeeded him, continued his favours to Abram: he was employed to teach the tsarâs grandson â the short-lived Peter II (1715â30; tsar 1727â30) â geometry and fortification. About this time he is first referred to as Gannibal. The acquisition of a surname was a step up the social ladder, differentiating him from the serfs and others known only by Christian name and patronymic; while that he should have called himself after the great Carthaginian general implies no lack of confidence in his own abilities.* His fortunes changed after Catherineâs death: under a vague suspicion of political intrigue he was posted, first to Siberia, then to the Baltic coast. It was not until the accession of Elizabeth, Peter the Greatâs younger daughter, that his situation improved. In December 1741 she promoted him major-general from lieutenant-colonel, and appointed him military commander of Reval. The following year she made him a large grant of land in the province of Pskov: this included Mikhailovskoe, the estate where Pushkin was to spend two years in exile, from 1824 to 1826. In 1752 he was transferred to St Petersburg, promoted general in 1759, and, in charge of military engineering throughout Russia, oversaw the building of the Ladoga canal and the fortification of Kronstadt. That a black slave, without relations, wealth or property, should have risen to this position is in the highest degree extraordinary: so remarkable, indeed, as to argue a character far beyond the common, one that was more than justified in appropriating the name and reputation of the great Carthaginian. Elizabethâs death in 1761 put an end to his career; he was retired without promotion or gratuity, and lived for the rest of his life in his country house at Suida, near St Petersburg, where he died on 20 April 1781.

In 1731 he had married Evdokiya Dioper, the daughter of a Dutch sea captain. When she gave birth to a child, who was plainly not his, he divorced her (though bringing up the daughter as his own), and married the daughter of a Swedish officer in the Russian army, Christine von Schöberg. Of his seven children by Christine (three more died in infancy) the eldest son, Ivan, was a distinguished artillery officer who reached the rank of lieutenant-general. Petr, the second son, in old age lived in Pokrovskoe, some four kilometres from Mikhailovskoe, where he occupied himself with the distillation of home-made vodka. âHe called for vodka,â Pushkin wrote after visiting him there in 1817. âVodka was brought. Pouring himself a glass, he ordered it to be offered to me, I did not pull a face â and by this seemed to gratify extraordinarily the old Negro. A quarter of an hour later he called for vodka again â and this happened again five or six times before dinner.â6 He visited him again in 1825, when he was thinking of composing a biography of Abram, a project which later turned into the fictional Blackamoor of Peter the Great. âI am counting on seeing my old negro of a Great-Uncle who, I suppose, is going to die one of these fine days, and I must get from him some memoirs concerning my great-grandfather,â he wrote on 11 August.7 He carried out the intention a week or so later, bringing back with him to Mikhailovskoe not only the manuscript of Abramâs biography, written by his son-in-law, Adam Rotkirch, but also a short, unfinished note composed by Petr himself, outlining his and his fatherâs careers.8

Osip, Abramâs third son and Pushkinâs maternal grandfather, was a gunnery officer in the navy, reaching the rank of commander. Careless and dissolute, he ran up large debts, which his father in the end refused to pay and forbade him the house. At the beginning of the 1770s he was posted to Lipetsk, in the Tambov region, where he met and, in November 1773, married Mariya Pushkina.* Mariya was generally held to have thrown herself away; her Moscow cousins made up an epigram on the marriage:

There was once a great fool,

Who without Cupidâs permission

Married a Vizapur.

The last line is a hit at Osipâs complexion; it is a reference to the âswarthy Vizapurâ, Prince Poryus-Vizapursky, an Indian and a well-known eccentric.9

Abram forgave the newly-married Osip; he was allowed to return home, and his daughter Nadezhda, Pushkinâs mother, was born in Suida on 21 June 1775. However, Osip found his father overbearing and family life excruciatingly boring. Leaving a note to say he would never return, he fled to Pskov, where he met a pretty young widow, Ustinya Tolstaya. Having received â so he said â a mysterious message announcing his wifeâs death, he married Ustinya in November 1778. Mariya, who was far from dead, lodged a complaint against him; after years of petitions and counter-petitions the marriage to Ustinya was annulled, and the estate of Kobrino outside St Petersburg (which he had now inherited, together with Mikhailovskoe, from his father) made over in trust to Nadezhda. Osip retired in dudgeon to a lonely existence at Mikhailovskoe, where he died in 1806, leaving the estate encumbered with debt.

After the separation Mariya moved to St Petersburg, spending the summers in Kobrino, some thirty miles from the capital. Nadezhda was therefore brought up in far from provincial surroundings. She was well-read, spoke excellent French, and through Mariyaâs relations in the capital gained entrée into society, where she became known as âthe beautiful creoleâ.10 Here she met Sergey Pushkin; the couple â the poetâs father and mother â were married on 28 September 1796 in the village church at Voskresenskoe on the Kobrino estate.