Полная версия:

Trojan Horse of Western History

After Schliemann’s death, in 1893–1894, his friend and colleague Wilhelm Dörpfeld studied the stratigraphy of the archaeological layers of the Hisarlik Hill in more detail and determined that nine cities had replaced each other in sequence during the course of nearly 4.5 millennia in that spot. Accordingly, the periods of Troy’s existence were numbered from 1 to 9. In Dörpfeld’s opinion, Homer’s Ilion lied in the sixth layer (Troy 6), which Schliemann ruthlessly destroyed during his first excavations. Dörpfeld arrived at this conclusion even despite the fact that no traces of military operations were found in relation to destruction of Troy 6.

In 1932 Dörpfeld’s business was continued by the expedition of the Cincinnati University, headed by Carl Blegen, a renowned American archaeologist. Blegen corrected his predecessor and proved that Troy 6 (1800–1300 B.C.) had perished due to an extremely strong earthquake. Blegen divided the Troy 7 epoch into three periods and suggested that Homer’s Troy had existed in the 7а period (1300–1100 B.C.), with its apparent signs of a siege and damage.

The diagram proposed by Carl Blegen in relation to the sequence of existence and destruction of ancient settlements on the Hisarlik Hill became a classical one.

Troy 1 (3000–2500 B.C.) dates back to the pre-Greek culture, as ancient as most ancient civilizations, such as the Egyptian, Sumerian, Aegean and Indus ones. Inhabitants of Troy 1 had no gold, but lived in rather good houses, called megarons, they used metal tools and bred sheep and goats.

Fig. 13. According to Dörpfeld and Blegen, the Trojan settlement is a kind of a sandwich cake. (Image © Nika Tya-Sen.)

Troy 2 (2500–2200 B.C.) was a large city of the Minoan culture with walls of four meters thick, cobbled streets and gates. The basic activity of its inhabitants was agriculture: manual grinding mills were found in almost every house of this city. They used potter’s wheels to make utensils. Troy 2 traded fabrics, wool, ceramics and timber in the huge territory from Bulgaria and Thrace up to Central Anatolia and Syria, which promoted noticeable growth of its financial well-being, demonstrated by a great number of golden and silver items found in this cultural layer, including the “Priam treasure” found by Schliemann.

The city was destroyed by a sudden fire, and locals had no time to collect their precious utensils. However, according to Blegen, the catastrophe “did not cause any significant damage to the settlement’s cultural development. Given the retention of the former civilization and absence of obvious traces of foreign influence, the culture of Troy 2 was gradually and steadily developed until its successor Troy 3 picked up the baton”.[25]

Troy 3 (2200–2050 B.C.) and Troy 4 (2050–1900 B.C.) were established on the site of the capital that burnt-down. They were protected with walls and occupied a large area. Despite the rather primitive (even compared to Troy 2) culture in general, the population of these cities improved upon cooking methods and notably varied their diet.

Troy 5 (1900–1800 B.C.) was a city with a quite high culture level given the samples of fine ceramics and building art discovered. Compared to the previous periods, the manners and habits of the citizens changed a lot. “One of the innovations that was introduced in Troy 5 (which archaeologists regret strongly) was procedding to a new and more efficient way of house cleaning. Now they swept the floor and cleaned it from the rubbish accumulated during the day; therefore, nowadays archaeologists can only rarely find animal bones, various small items discarded and lost, as well as whole or broken ceramic vessels”.[26] Like the previous cities standing on Hisarlik Hill, Troy of that period was destroyed, although the cause for this remains unknown: there are no traces of a fire in the ruins of buildings, and nothing would confirm that the city was captured by enemies.

Fig. 14. The Southwest (Scaean) gate where Schliemann excavated the “Priam treasure” dates back to the Troy 2 period.

Troy 6 (1800–1300 B.C.) was a really great city with block walls of 5 meters thick and with four gates, with squares and palaces. Its population were people of foreign traditions, who apparently came there from another place and brought their own cultural legacy with them. They tamed horses, established a custom of cremation of the deceased, and perfected the art of weapons production. As early as in the beginning of the Troy 6 period, the range of pottery wares had been changed to something new. This city was leveled by an earthquake, as evidenced by specific cracks on walls of buildings.

According to the legend, Ilion was founded by Ilus, son of Tros. Then the power was overtaken by Ilion’s son Laomedon. During its times, Troy achieved might and established control over Asia Minor, Propontis (the Sea of Marmara) and the straits. Laomedon erected a “city on the top of the hill”, the walls of which were built by Poseidon, who ended up a slave to Zeus (by Zeus’ will) together with Apollo, ordered to pasture Zeus’ oxen. For their assiduous work, Laomedon promised to pay the gods, but changed his mind and, in the end, just expelled them from the country, threatening to cut their ears off (Ilus. XXI, 440–458). Then Poseidon sent a sea monster to Ilion to devour all the people. It was when Heracles came in and killed the monster, getting into the monster’s belly and hacking all its entrails. For this feat, Laomedon promised him magic horses but once again failed to keep his promise. Nothing to be done, Heracles had to destroy the city, to kill Laomedon and to shoot all his heirs to death by bow and arrow, and to give the king’s daughter Hesion[27] to his friend Telamon. At the same time, Hesion was allowed to release one of the captives. She chose her younger brother Podarces and paid for him with her headscarf. Since then, Podarces was called Priam, meaning “redeemed”.[28] Thus, the legend obviously referred to the times of Troy 6, and the earthquake that destroyed the city was interpreted as anger of Heracles.

Fig. 15. That’s what Troy 6 looks like to our contemporaries. (Image © Nika Tya-Sen.)

Who were the founders of Troy 6, so noticeably different from the cities of previous periods? Blegen was sure that they were Greeks; however, he could not know for sure how they departed for new lands. He wrote, “They did not manage to define whether they roamed from the North to the shore of the Aegean Sea, or sailed from the South of Russia across the they arrived in Greece by sea from the West or the East. There are no hints left by either ceramics, artefacts, or horse bones”.[29]

Fig. 16. The fortification wall and the East gate of Troy 6 (15th – 13th century B.C.).

Troy 7 referred to the period 1300–1100 B.C. The Trojan War is considered to have taken place during that period. There are some calculations based on different methods, but most of them put this era at between 1220 and 1180 B.C.

The ancient writers could only estimate the dates of the Trojan War, according to the approximate number of generations up to the first Olympic Games, epical tradition, etc. And they arrived at different results, ranging from the 14th to 12th centuries B.C. There were other methods, too, including the study of archaeological artefacts, epigraphy, etc.

The unique method was applied in 2008 by Marcelo Magnasco, Professor of Physics and Mathematics of the American Rockefeller University, and Constantino Baikouzis, astronomer from the Argentina’s La-Plata Observatory.[30] They took note that according to Homer when Odysseus was beating the grooms seeking to marry his wife Penelope,

…the sun has perished out of heaven and an evil mist hovers over all

Odyssey. XX. 356–357and they decided that this text pertained to a solar eclipse. The dates of solar eclipses, both in the past and future, can be easily calculated. Having compared these dates with other astronomical data provided in the text, scientists concluded that King Odysseus returned to Ithaca on April 16th, 1178 B.C. According to Homer, Odysseus’ wandering after the Trojan War took about 10 years. Thus, according to Magnasco and Baikouzis, the Trojan War could have been limited with chronological frame of 1188 and 1198 B.C.

After the earthquake, the city was built up again. There were no traces of people in the ruins of Troy 6, and Blegen concluded that the population survived and immediately after the earthquake ended they returned to the city and started to restore their houses. In due course, the city became more populated, as the streets became more compact and the houses became smaller. However, traces of imported goods and wealth vanished. In general, Troy 7 was nothing of the majestic city “rich in gold” described by Homer.

The city that belonged to the first phase of Troy 7, deemed as 7а (1300–1260 B.C.), was destroyed by fire. The territory of the settlement was once again covered with loads of stones, mudbricks and various wastes, burnt-down and half-burnt-down. Fragments of human bodies found in this layer point indicated that citizens died through violence. Thus, according to Blegen, Troy 7a was destroyed due to the city having been captured and citizens dying. “The crowding of numerous small houses anywhere a free place could be found points to the fact that the fortress walls were protecting many more citizens than before. Numerous uncountable capacious vessels for food and water standing on floors of virtually every house and room indicate the need to store as much food and water as possible in case of emergency. What else could that emergency be than the enemy siege?”[31]

Upon analyzing the Mycenaean pottery discovered in the cultural layer of the burnt city and comparing it to the chronology of ceramics of Arne Furumark,[32] Blegen realized that most of these samples referred to type 3 B dated first half of the 13[[th]] century B.C. Samples classified as the earlier type 3A is sparsely encountered in this layer, and there are no items of the later type 3C. On this basis, Blegen concluded that Troy 7a had been destroyed in approximately 1260, two generations earlier than the Mycenaean civilization declined. “Most of large Mycenaean cities in continental Greece (perhaps, but the cities of Attica) were destroyed in the end of the era when Mycenaean pottery classified III B was produced… Approximately by 1200 B.C., might of Mycenae waved; large cities, the population of which was referred in the Catalogue of Ships as the core of Agamemnon’s troops marching against Troy, were in ruins, and the survivors faced an even more difficult struggle for survival. The period, when type 3C pottery was used every day was characterized by people’s impoverishment and culture level decline, and only memories of Mycenae’s former glory remained. The Mycenaean kings and princes couldn’t unite their forces and leave to capture other lands. That was only possible much before that, when the Mycenaean civilization was at the height of its political, economic and military power, when splendid emperor’s palaces hospitably met dear guests in their entire splendor. The fortress was seized and burnt before the mid-13[[th]] century B.C., which was when the type 3B Mycenaean pottery was only introduced in Troy 7a being prosperous yet, and the type 2A pottery was doling out the seat.

Fig. 17. Carl Blegen affirmed that Troy 7a had been seized and burnt in the mid-13th century B.C. and argued this on the basis of the prevalence of type 3B Mycenaean pottery in its cultural layer. (Image © Olga Aranova.)

Thus, Troy 7a must have been the mythological Troy, a fortress with its sad fate, whose seizure attracted attention and awoke imagination of its contemporaries – poets and narrators, whose stories about the heroes of that war passed by word of mouth from generation to generation. There is no doubt that some details of those stories were forgotten and omitted in due course, and that some other things were made up. This had been going on until these legends reached the ingenious poet, who collected all the different stories and wrote two epical poems that survive until our day”.[33]

Carl Blegen identified Troy 7a as Homer’s Ilion. Troy 7a came to its end being captured by the enemy after a continuous siege. However, there is no proof that it was captured by the Greeks.

The results of excavations of the next cultural layer, relating to the phase of Troy 7b (1260–1190 B.C.), indicate that many inhabitants of this burnt city had survived. Soon after the conquerors left, the citizens returned and built new houses right on the ruins and, and the city rose by approximately one meter as compared with the previous ground level. However, the city that used to be great failed to return to its former power. The population got poorer and left the city. At the same time, the fortress wall wasn’t damaged, as it had happened before. Blegen wrote, “It looks like everything happened quietly enough: having simply cast the citizens out of their houses, new tenants moved in”.[34] The tribe that settled there brought some coarse pottery along, made without a potter’s wheel, which became kind of a business card for Troy 7b. According to some explorers, that moulded pottery with bumps, just like some other primitive bronze utensils found in the same layer, were obviously related to similar goods found in depositions of the late Bronze Age in Hungary.

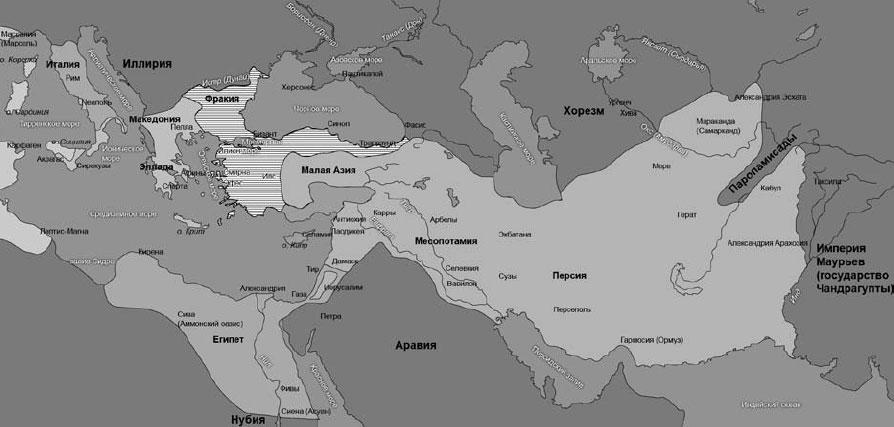

The next devastation to the city caused by fire completed the history of ancient Troy. For 4 centuries, the city remained empty – its inhabitants might have found a quieter place for living. New Troy – Troy 8 (700–85 B.C.) – already belonged to the Greek world entirely. It is known under the name of Ilion, though, many scientists specialized in antiquity have categorically rejected its connection with Homer’s Ilion.[35] This city was not as mighty, as it changed states several times. In 480 B.C., King Xerxes visited that very city, and Alexander the Great came there in 334 B.C. After his empire had collapsed, the city was overtaken by Lysimachus, who exercised his “special concern for the city,” according to Strabo.

Then Ilion became part of the Roman Empire, and bathhouses, temples and theatres were built there. However, in 85 B.C., due to conflicts with Rome, the city was again plundered and destroyed – this time at the hands of the troops of Roman vicar Gaius Flavius Fimbria, who captured the city during the war against Mitridate Eupatore.

Fig. 18. Division of Alexander's empire after the battle of Ips (301 B.C.) The Lysimachus empire is dashed.

Fig. 19. The Roman odeum of Troy 9 (from 85 B.C. till 500 A.D.).

When Fimbria began boasting that he captured the city on the 11th day, whereas Agamemnon did it only in the 10th year with great difficulties and having a fleet of 1,000 vessels, and the whole Greece aiding him in the campaign, one citizen of Ilion remarked, “True, but we did not have such a defender as Hector”.[36]

Troy 9, dated 85 B.C. – 500 A.D., was restored by Lucius Cornelius Sulla, who routed Fimbria. Then it was dynamically developed in times of Julius Caesar and Octavianus Augustus. By 400 the city appeared to be deserted, and all geostrategic advantages were gained by Constantinople. In due course, Troy turned into a hill that Heinrich Schliemann would dug up into historical oblivion 1500 years later.

Chapter 3

The War for Troy, 20[[th]] century

A tour around the Trojan archaeological reserve starts at the Eastern gate, relating to the period of Troy 7. It seems not to be a coincidence: upon entering the area of the great city, you immediately feel its mighty walls and involuntarily identify yourself with its defenders. The path, marked with coloured ribbons (anything can happen to tourists!), goes near the Northern bastion with a wonderful sight-seeing platform, along the Athena temple discovered in 1865 by Franc Calvert, an ancient citadel of mudbrick and megaron houses built a thousand years before the Trojan War, and the Schliemann’s trench looking like a bad wound on the body of the elderly hill…

If you do not take pictures of every stone or stay at the information stands for too long, you can walk along the tourist path in 10–15 minutes. The mighty fortress is only 200 meters in diameter.

200 multiplied by 200 is 4 hectares, which approximately matches the ground space of five football fields or one modern not-too-large megamall. How was it possible to accommodate 50,000 defenders of Troy here, as Homer had written? Let’s assume that most of them had stayed outside the bastion. In the early 1990s, Helmut Becker and Jorg Fassbinder, employees of Manfred Korfmann, made a discovery by means of magnetic survey: in the 13[[th]] and 12[[th]] centuries B.C., the Trojan citadel was surrounded by a big downtown protected with two outer circles of walls, and a ditch, cut off in the rock half a kilometer away from the fortress. Thus, territory of Troy extended about five times further and was as large as the Moscow Kremlin. Nevertheless, there were 50,000 people, who had to sleep a bit more comfortably than in standing position and to maintain cattle, battle horses and chariots! In such area, it was only economically justified, as Margaret Thatcher would say, for no more than 5 thousand people to live there. Korfmann said 7,000 would have fit it. Let it be, but surely no more than that!

Fig. 20. Megarons of the 23rd century B.C. are protected from bad weather with a canvas roof and ribbons are to guard against too curious tourists.

However, the figures provided by Homer have long been considered as poetic exaggerations – 29 empires in the Achaean coalition, 1186 ships filled with soldiers (from 50 to 120 people on every ship, more than a hundred thousand in total!), and 10 years of siege…

But many questions still have no definite answers, in particular, because of the damage done by Schliemann. Who were the Trojans? What was their nationality? What language did they speak? Why did most of them have Greek names? Who did the Trojans pray to, and why did some Greek gods help them? If the Greeks really captured Ilion, why didn’t they use the victory advantage and capture the country or even leave their vicar there? Was there the great Trojan War real, or was it just a poetic image of many independent military campaigns, forays and sieges that took place during dozens or even hundreds of years?

These questions were asked especially often since the legend about the Trojan War seemed to have been completely confirmed by finds made by Schliemann, Dörpfeld and Blegen.

Doubts about historicity of the Trojan War revived, when the legend about it seemed to have been completely confirmed by finds made by Schliemann, Dörpfeld and Blegen.

A kind of Renaissance of views of the late 18[[th]] and early 19[[th]] centuries happened, when doubts about the historical reality of both the Trojan War and Troy itself were very popular.

While Ancient thinkers considered Homer to be not only the most skilful poet but also the greatest scientist, and his poems to be a source of the truest historical and geographical information (according to Strabo, “Homer surpassed all people of the ancient and new time, not only due to the high dignity of his poetry, but… knowledge of the conditions of public life”[37]), the science of the Modern Age completely subverted his authority. Not only was the information about the events described in the Iliad and the Odyssey considered to be unreliable, but the very existence of Homer was put into question. Scientists’ skepticism reached the point that for some time believing that there was some considerable culture in Aegis before the 1st millennium B.C. was considered madness.[38] According to their judgments, all these “rich in gold Mycenae”, “blossoming Corinthes” and “magnificently arranged Troy”, inviting envy by their riches even amongst Greeks of the classic era, were only imaginary cities populated with fiction characters – the descendants and relatives of the Olympic gods, such as Agamemnon, Achilles, Diomidius and Priam. At the same time, there have always been scientists, who trusted in Homer’s word and were ready to defend their point of view.

At the turn of the 18[[th]] and 19th centuries the harshest arguments about Homer took place. The ones being in doubt were Englishmen John McLaurin, who published Treatise in evidence that Troy was not captured by the Greeks (1788), and Jacob Bryant, who published Treatise concerning the Trojan War and expedition of the Greeks as it was described by Homer, demonstrating that such expedition had not ever been held, and that such a city of Phrygia hadn’t existed (1796). The latter violently polemized about historicity of Troy with archaeologist Lechevalier, the very person who first located Ilion in the Bunatbashi area. “Cabinet critics heatedly argued about trifles – location of the Greek ships and even the probable number of children born by camp whores”.[39]

At the very height of the scholarly battles, the great romantic Byron visited the plane at the Hellespont coast. The atmosphere of these places made him believe that Homer’s poems were true. 11 years later he wrote in his diary, “I stood upon the plain daily, for more than a month, in 1810; and if anything diminished my pleasure, it was that the blackguard Bryant had impugned its veracity (the Trojan war)… I venerated the grand original as the truth of history (in the material facts) and of place. Otherwise, it would have given me no delight. Who will persuade me, when O reclined upon a mighty tomb, that it did not contain a hero? – its very magnitude proved this. Men should not labour over the ignoble and petty dead – and why should not the dead be Homer’s dead?”[40]

Despite such poetic arguments by Byron, the belief that the Trojan War was only the fiction of the blind Homer remained popular among scientists for another half a century until Schliemann’s excavations assured the scientific community of the historical value of great cities described in the Iliad, such as Troy, Mycenae, Tirynthos and Orchomenus. At first sight, some finds of the amateur archaeologist accurately corresponded to the items described by Homer. For instance, the blade of a bronze dagger found in Mycenae depicted the famous tower shield; in the Iliad, such item belonged to Ajax.

Fig. 21. Hellespont in the Canakkale District.

Other items found were the remains of a helmet made of wild boar fangs, depicted in the 10[[th]] rhapsody of the poem, and so on. All these seemed to be sound proof that the Trojan War had been real. And Homer himself already seemed to be at least a younger contemporary of his heroes or even an immediate witness of the events he described. “Data provided by Homer gradually became kind of “a guidebook” for those studying the Aegean culture of the Mycenae epoch”.[41]

However, Schliemann’s romantic epoch ended up quite quickly. Already in the late 19[[th]] century, serious studies were performed, demonstrating that the material culture and everyday life of the Homer’s heroes did not correspond to the cultural environment of the Mycenae civilization and should have been associated with a later period.[42] Having armed his characters with iron weapons and darts known in the Bronze Age, Homer ignored all typical signs of the Mycenae culture, mentioning neither cobbled roads with bridges, nor water lines and water drains in the palaces, nor the fresco paintings. Even written language that already existed before the 12[[th]] century B.C. and was demonstrated in clay plates found by Arthur Evans at the beginning of the 20[[th]] century during the Knossus excavations on Cyprus, wasn’t mentioned by Homer. Thus, it appeared that when the Iliad and the Odyssey were written, the Mycenae civilization had been already forgotten. Thus, trustworthiness of Homer’s stories were once again put in doubt.