Полная версия:

Trojan Horse of Western History

It is noteworthy that things in the West go as such: academic circles there still accept the old “classical” translations of Homer, although, for the purpose of public enlightenment, they issue cut versions of the Iliad and its brief narrations, or even comics. In due time, the novel by Alessandro Baricco An Iliad[9] became a box-office project. This Italian writer tries to interpret the classic poem in a new way, removing everything that had to do with Gods, fate and other empyreans from it, which a modern reader would be unable to understand.

Well, even in the book-concerned 19[[th]] century the Iliad was not considered to be entertaining reading. In 1884 Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff, maybe the greatest Homer specialist of that time wrote, “Now Homer is no longer a widely read poet… Even most philologists largely know him as poorly as Christers know the Holy Bible”.[10] We hope to refer to Mr. Wilamowitz again and again in our work. Now we simply state that most of the people living today, just like the generation of our grandparents, have not read Homer thoroughly and thoughtfully enough to ask the essential questions:

1. Did Troy really exist or was it only a myth, and is it useless to look for it on the perishable Earth?

2. Did the Trojan War really take place, or is it a poetic fabrication intended to make people think about the nature of force and weakness, bravery and cowardice, anger and generosity, about boredom of immortality and greatness of death?

3. Did the Greeks win that war, as Homer and the whole antique tradition insisted, or have we been for a few thousand years captivated by false ideas, unintentionally or intentionally formed for us by writers of the distant past?

4. And above all, what lessons can we learn from this story for our up-to-date life, and more specifically, what lessons can be derived for us, the Russians?

Now we are in Troy to try and answer these questions.

Chapter 2

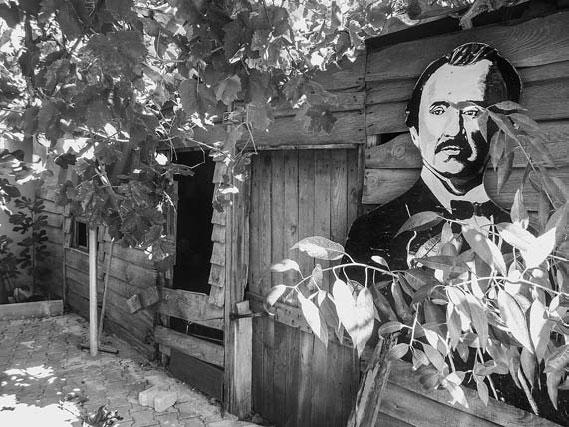

The Adventurer Who Tripped Over Troy

Heinrich Schliemann is really worshipped in the Troy archaeological reserve. Portraits of this international adventurer are literally everywhere: in souvenir shops, on covers of guide books, in informational boards and even in the above-mentioned model of the archaeologist’s house, which workers of German television made to shoot a documental. Almost 150 years ago Schliemann showed the locals something that was not a gold vein but at the least made it possible for them to always have some “tea” and “fish” on their tables (“çay bardak”, “balyk tabak” – the Turkish language is quite associative for the Russians). Those who aren’t involved into excavation works restarting from time to time, take a job in the tourist industry: they rent rooms, sell fridge magnets and guide tourists. We’ve met two country boys in one of the dusty streets of Tevfikye. Having noticed visitors from afar, they put their sun-tanned arms out in hope for baksheesh, a habit formed over many generations. We give them a lira each. It can’t be helped. Youngsters…

Heinrich Schliemann himself played the leading role in formation of the Schliemann cult. A master of self-promotion, he invented quite a number of legends about himself, the majority of which are still living.

Fig. 9. The false house of Schliemann in the village of Tevfikye was built by the Germans.

Most modern biographies of Schliemann are based on his autobiography, which was long ago acknowledged to be a rather doubtful source. For example, check the frequently republished biography of Schliemann, considered to be classical, written by the German historian Heinrich Alexan der Stoll.[11]

According to one of them, Heinrich Schliemann was born in a poor German family and became keen on Troy when he was eight, after he had got an illustrated History of the World by Georg Ludwig Jerrer for Christmas. The book contained a picture of Ilion aflame with its huge walls and gates, through which Aeneas fled with his father on his shoulders. Not wishing to believe that Troy was only a fairy tale told by Homer, the boy decided by any means to find the legendary city. It is commonly believed (and guides leading tourists in Troy insist on this very version) that Schliemann was the only man all over the Earth, who believed that the Trojan War had really taken place. Using geographic hints from Homer’s poems, he found and excavated Troy! Since that time, everything written by Homer started to be taken as the absolute historical truth.

The only one who believed… Well, if an outright lie can be called a wrench, let’s call it a wrench. But first of all, let us tell you about the kind of person that Schliemann was.

Heinrich Schliemann was raised in a troubled family (his father, a Protestant priest, was a libertine and an embezzler of state property), and he had to earn his living from the age of fourteen. For five long and boring years, he had been working as an errand boy in a grocer’s before he decided to change his life cardinally and applied for a job as a sea cadet on a schooner sailing to Venezuela. The vessel ran into a storm, and Schliemann told that he was among the few survivors. According to the newspapers, there were no victims in that shipwreck, though, but why would anyone bother spoiling such a wonderful story with some truth…

It was so much more interesting to imagine himself like Robinson Crusoe setting his foot on the Dutch land with a torn blanket over his shoulders. Anyway, having found a job in one of the trade houses of Amsterdam, Schliemann started studying languages. Schliemann’s gift for languages was an authentic medical fact. He mastered fifteen languages, including Russian, which, by the legend, he studied from pornographic poems by Barkov.

The “Schliemann’s” method of language studying is rather popular today; its essence is in the oral narration of text fragments in the foreign language. Step-by-step memory gets used to a new language, and receptivity to the new type speech increases. It is interesting that most adherents of this method have no idea of what Heinrich Schliemann did besides these studies.

Knowledge of Russian allowed Schliemann to come to Russia as a commercial representative. One year later, in 1847, he took out Russian citizenship. The newly-minted “Andrei Aristovitch” founded his own company and quickly grew rich supplying the indigo dye and Chilean saltpetre. He was into any business that promised profit. Of course, at the time of “gold fever”, Schliemann was in America, buying gold sand from gold diggers for a mere song and thus doubling his fortune. During the Crimean War, Schliemann was selling weapons to both sides, but he made a greater profit supplying cardboard-soled boots to the Russian army. Before abolition of serfdom in 1861, Schliemann bought up paper necessary for printing large posters with the manifest to resell it to the Russian government at an exorbitant price…

In 1864, having left his Russian wife Yekaterina Lyzhina and his three children in St. Petersburg, Schliemann set off for a journey around the world. He visited the ruins of Carthage in Tunis, remnants of Pompeii in Italy, ancient temples in India and Ceylon, the Great Wall of China and the Aztec ruins in Mexico. Shocked with everything he had seen, he signed up for to attend lectures on antique history and archaeology at Sorbonne. In 1868 Schliemann made his first excavation on the Greek island of Ithaca, which lasted for only two days. Having found a couple of shards in the ground, Schliemann, without a shadow of a doubt, passed them off as items that once belonged to King Odysseus himself.

After that the businessman visited Mycenae and the Asianic coast of the Dardanelles, where having missed the ship to Istanbul, he got acquainted with American consul Frank Calvert. Schliemann published the results of his journeys in his book Ithaca, Peloponnesus and Troy, for which he managed to obtain a doctoral degree from the so-so University of Rostock. The degree was conferred on him in absentia, as the competitor was visiting America to deal with issues of getting American citizenship and divorcing his Russian spouse.[12]

However, the scientific European community did not take his research seriously, and Schliemann decided to submit some foundational proof, having dug out an ancient city or, at least, something that could have possibly passed off as the traces of it…

Was Schliemann the first to search for the ancient Ilion in the North-Western Turkey, as it is often announced? No way. Even the laurels of the first explorer of Hisarlik are not rightfully his.

As it is set now, it was not difficult to find Troy; supposing that city was mighty enough to fight against the unified forces of the entire Greece, it should have controlled main trade ways, and, thus, it should have been in a prominent location. Moreover, “nature abhors a vacuum”, and if there is a city on a crossroad of trade routes, it will be restored after any defeat. So, today there must be a city engaged in the same business as Troy was in due time, monitoring routes and growing rich. It is not necessary to be as wise as Solomon to guess that this city is Constantinople-Istanbul, which is great due to the fact it controls the straits from the Black and Marble seas into the Aegean and Mediterranean Seas. There are two straits; Istanbul is located on the Bosporus, and its great predecessor apparently was on the Dardanelles. The geographic details in Homer’s poems point at them. At the same time, as Constantine the Great noted, being on the Hellespont is even more favourable, as not only the sea-gate but also the land-gate between Europe and Asia can be controlled. There was no better place for a city.

After it becomes clear, it is necessary to estimate and consider how far the sea had moved over three thousand years after the events described, and to look for some hills and fortress ruins at the entry to the Dardanelles, and to hear some legends from the locals…

The first scientific attempts to determine the precise position of Troy date back to the 18[[th]] century. In 1742 and 1750 the Englishman Robert Wood made two trips to the Troad and put his impressions in the book An Essay on the Original Genius and Writings of Homer. Despite he believed it was senseless to search for Troy, as it had been destroyed to the ground, Wood was the first person to suggest that the place where Troy had been changed for the worse since the ancient times. The harbour became silted, and the rivers changed their flow. His book was reissued 5 times in four languages and caused some public reaction of the scientific community.

In 1768, 1 year before Robert Wood’s book was issued, Baron Johann Hermann, a student of the glorified nationalist Johan Winckelmann, the founder of modern ideas about antique art, travelled around the Troad. After this journey he was the first to voice the hypothesis that ancient Troy must have been in the area of the Hisarlik Hill, located several kilometers away from the coast. The German cartographer Frantz Kauffer (1793), the mineralogist Edward Clark (1801), who later became a Cambridge University professor, and Charles McLaren (1822), the author of The Theses on the Topography of the Trojan War, also identified Hisarlik as the location of ancient Troy.

Jean-Baptiste Lechevalier, a French archaeologist, put forward another hypothesis. In 1785 he walked all the way from Hellespont to the Ida Mountain Range with the Iliad book in his road bag and using Wood’s book as a guide. Lechevalier was convinced that Homer described the geographic features of the peninsula rather accurately. The French scientist decided that the spot was close to the village of Bunarbashi (Pinarbashi) in the Scamander River Valley.

In 1864 the Austrian diplomat and traveler Johann Georg von Hahn decided to practically check the hypothesis of Lechevalier. Having started an excavation near Bunarbashi, von Hahn discovered the traces of some settlement. However, it became clear later that those remnants of ancient buildings dated back to a later period from 7[[th]] to 5th centuries B.C.

In one year Frank Calvert led a test excavation in Hisarlik. Two generations of his family had lived near the Troad already, and Calvert had perfect knowledge of the region. But the real revolution in his world-view happened after 1849, when he met the famous Russian scientist Pyotr Chikhachev. Chikhachev, better known in Russia as the pioneer of the Kuznetsk coal basin, had authored about 100 scientific works on geology and paleontology of Asia Minor, and the most detailed map of the Troad was based on his topographic studies. By accompanying Chikhachev on his expedition, Calvert gained invaluable experience and knowledge in the field of archaeology and geology, but, most importantly, he started to believe the Russian scientist’s statement that Troy should have been searched in the depths of Hisarlik, a part of which he acquired later.

Calvert came to believe that Troy should have been looked for in the depths of Hisarlik after the famous Russian geographer Pyotr Chikhachev, whose role in the discovery of this ancient city has still not been acknowledged by the descendants.

Chikhachev’s role in the discovery of Ilion remained unnoticed by the descendants, and all the victorious palms passed to Schliemann, who in turn claimed them for himself rather than Calvert. The man who identified the location of Troy was undeservedly forgotten, as, alas, is a frequent occasion in history. Today only the Altaic mountain range named after him and the commemorative plaque in Gatchina remind us of the merits of this scientist.

While making the digging in Hisarlik in 1865, Calvert came across traces of the Temple of Athena and of the city wall that built by Lysimachus. At that the diplomat’s financial opportunities exhausted. Calvert had hoped to continue the search after meeting the conceited millionaire Schliemann, who believed that the ruins of Troy were in the spot, where Lechevalier had identified them – in Bunarbashi. Later Calvert affirmed that in a letter to The Guardian newspaper: “When I first met Doctor [Schliemann] in August, 1868, the Hisarlik and the Troy location were new subjects for him”.[13] Schliemann denied everything and even launched a full-scale war in the press against Calvert, charging him with lying. There are no document dated before 1868 that would testify to Schliemann being engaged in the Trojan issue at all. According to the historian Andrei Strelkov, Schliemann simply “tripped over Troy” during one of his travels.[14] However, the businessman presented it all as if he had been looking for Troy for all his life and selected Hisarlik as the site to excavate the ancient city, basing on hints of Homer. To eliminate any mentioning Calvert in the history of the Troy’s discovery, Schliemann invented a story about the dream of his childhood and the illustrated book,[15] and introduced himself as a man truly possessed by Homer’s epos, and even gave the children born of his new Greek wife Sophia the names of Engastromenos,[16] Agamemnon and Andromacha.

Fig. 10. Karl Bryullov. Portrait of P. Chikhachev (1835).

Thus, was all of it happened later, and in August, 1868, Calvert saw the dear visitor in his house on the shore and convinced him to join the excavations assuring him, “All my land [on the Hisarlik Hill] is at your disposal”.[17] Having felt the scale of profit in case they succeeded, Schliemann agreed to take part in the project. As early as in December he started consulting with the highly experienced Calvert about organization of excavations, in particular – in regard to quantification of mattocks and shovels for the works. At the same time he negotiated with the Turkish government for a license for archaeological works.

At last, on October 11, 1871 having employed workers in the near villages, Heinrich Schliemann started soil works. Calvert tried to prevent his comrade from hasty decisions and advised him to carry out the sounding of cultural layers of more than 17 meters deep, at first. However, Schliemann, being sure that Homer’s Troy was the most ancient thing of everything possible, decided to dig down to the very continental plate.

Long trenches up to seventeen meters deep and wide ruthlessly cut up the Hisarlik Hill, until Schliemann managed to dig down to an ancient settlement, destroying everything of no interest to him and not shining under the sun. Schliemann announced that he had discovered the ruins of the city of Priam.

The merchant’s barbarous approach to excavations not only deprived future scientists of the most valuable archaeological information, but also resulted in destroying the traces of the old city he had discovered. Left to the mercy of fate in the aggressive environment, they began to crumble and get weathered, suffering from roots of trees and bushes.

They managed to halt the destruction process only in 1988, when expedition participants began to protect the walls of the ancient citadel by their own efforts, led by Professor of Tubingen University Manfred Korfmann.

The thickness of the cultural layer of seventeen meters, though accumulated for some thousands of years, seemed unbelievable until we learned about their origin. “Fires often occurred, as wood and straw were used for construction [during the Bronze century],” Professor Carl Blegen explained, who used to excavate Hisarlik Hill in 1932–1938. “When a house burned down, its roof would collapsed and its walls would scatter. […] Since there were no bulldozers or graders then, nobody tried to clear the site of the fire or to remove the waste. It was much easier to level the site, covering the not remaining fragments of a building with a thick layer of waste (which ensured the noticeable growth of the cultural layer), and then to build a new house on the same spot. In Troy, such things happened rather often, and every time the ground level rose by 80–100 centimeters. Steady growth of the cultural layers on the hill also occurred due to other factors. For example, floors in all dwellings but palaces and magnificent private residences were made of earth or compacted clay. People weren’t used to collect domestic and kitchen wastes at certain special sites then. So, all wastes, including bones, food waste and broken utensils were left on the floor of the dwelling or were immediately chucked away to the outside. Sooner or later, the floor appeared to be covered with animal bones and wastes so much that even hosts with strongest stomachs understood that something should have been done about it. Solving the issue was simple and rather efficient: waste from the floor was not cleaned out, but was covered with a thick layer of fresh clay, which was compacted after that. During the excavation, the archaeologists often discovered houses, where that process was repeated many times until the floor level appeared too high for normal living, and it would have become necessary to lift the roof and to rebuild the entrance”.[18]

Schliemann continued his excavations for three seasons, and finally, on May 31, 1873, he came across some real treasures at the surrounding wall near the southwest gate, at a depth of 8.5 meters. Here is how he described those events:

In excavating this wall further and coming closer and closer to the ancient building and to the North-West from the gate, I came upon a large copper article of the most remarkable form, which attracted my attention all the more as I thought I saw gold behind it.… In order to withdraw the treasure from the greed of my workmen, and to save it for archaeology… I immediately had “paidos” called.…This word is of unknown origin; it came into the Turkish language and is used instead of the Greek άνάπαυσις, meaning rest time. While the men were eating and resting, I cut out the Treasure with a large knife…. It took huge efforts and involved risk, as the fortress wall, under which I had to dig, could fall down on me any moment. However, the view of so many subjects, every one of which was of great value for archaeology, made me fearless, and I did not think about any hazards. It would, however, have been impossible for me to have removed the Treasure without the help of my dear wife, who stood by me ready to pack the things which I cut out in her shawl and to carry them away.[19]

In the niche discovered by Schliemann, a set of 8830 precious metal articles were found, including necklaces, diadems, rings, brooches and bracelets. Owing to Calvert’s brother Frederic, it was possible to take the treasure to Athens. Having placed it to a bank, the businessman told journalists

Fig. 11. Schliemann’s trench with traces from the early Bronze century.

that he had found neither more nor less than the treasures of the Trojan King Priam. This sensational news covered front pages of newspapers, and the photograph of Sophia Engastromenos in “Helen’s attire” was published everywhere. Schliemann provided pictures of these treasures in his book The Trojan Antiquities, issued in 1874 by the famous publisher Friedrich Arnold Brockhaus.

The scientific community, which previously paid no attention to entertaining claims of the dilettante, launched a squall of criticism against him. Professional archaeologists were shocked with the barbarity by which Schliemann literally ripped the cultural layers of the ancient hill to pieces and destroyed many of the more recent constructions.

Many questions were also asked in relation to Schliemann’s story being more like a plot of an adventure novel. As it was learnt later from Sophia’s correspondence with her husband, she could not have participated in transportation of the treasure, as she was in Athens then.[20] Besides, the content of the treasure was also doubtful. For example, the golden bulb of 23 carats for drinks suspiciously resembled a sauceboat of the 19[[th]] century and, within the meaning of Schliemann’s letter sent to his Athenian agent on May 28, 1873, in which he asked to find a reliable jeweler, this claim was taken to verify that the “Priam treasures” were a fake. According to another version, the “treasure” could have been made of items previously acquired either in Istanbul markets or found at different times during excavations in Hisarlik.[21] One way or another, the treasures could not have belonged to legendary Priam, as they were found in the cultural layer being a thousand years older than Homer’s Troy.[22]

Fig. 12. Sophia Engastromenos in the “Great Diadem” from the “Priam treasure” (1874).

The treasures found by Schliemann could not have belonged to legendary Priam, as they were found in the cultural layer that was a thousand years older than Homer’s Troy.

The Sublime Porte read the newspapers, too, and having learned about Schliemann’s unprecedented smuggling, sued him for ten thousand francs. Silently grinning, the millionaire reimbursed the damage, added extra forty thousand and declared himself the absolute owner of the treasures. Later Schliemann made several attempts to place them in museums in London, Paris and Naples, but they refused to take the treasures for political and financial reasons.[23] In 1881, Schliemann eventually presented the “Priam treasures” to the city of Berlin, having received the title of the “honourable citizen of Berlin” in exchange, a title, that was previously conferred to Chancellor Otto von Bismark. The treasures remained there until Professor Wilhelm Unverzagt transferred the Trojan finds to the Soviet Command in 1945 according to contribution conditions. For a long time, the collection was considered to be lost, but it was actually stored in strict confidence in the Pushkin Museum of Moscow (259 items, including the “Priam treasures”) and in the State Hermitage (414 items made of copper, bronze and clay). It was only in 1993 that Yeltsin’s Government declared that the most valuable part of the Trojan treasures were being kept in Russia. On April 15[[th]], 1996, the trophies were exhibited in the Pushkin Museum for the first time.[24]

Having found the “Priam treasures”, Schliemann did not cease his exploratory activity and continued to dig out Mycenae, Orchomenos and Tiryns. He returned to working at the Hisarlik Hill for three times. While different people think differently about Schliemann’s activities, it is noteworthy that his adventures not only peaked scientific interest in the history of Troy, but also resulted in discovery of the previously unknown Aegean civilization. Schliemann never learned about it and died in certainty that all his finds were only related to the Trojan War era.