Полная версия

Полная версияLost and Hostile Gospels

The Pharisees, and those of the Sanhedrim who had not fallen into his hands, sought safety in flight. It was then probably that Jehoshua, son of Perachia, went down into Egypt and was accompanied by Jeschu.

Jehoshua was buried at Chittin, but the exact date of his death is not known.85

Alexander Jannaeus died B.C. 79, after a reign of twenty-seven years, whilst besieging the castle of Ragaba on the further side of Jordan.

It will be seen at once that the date of the Talmudic Jeschu is something like a century earlier than that of the Jesus of the Gospels.

Moreover, it cannot be said that Jewish tradition asserts their identity. On the contrary, learned Jewish writers have emphatically denied that the Jeschu of the Talmud is the Jesus of the Gospels.

In the “Disputation” of the Rabbi Jechiels with Nicolas, a convert, occurs this statement. “This (which is related of Jesus and the Rabbi Joshua, son of Perachia) contains no reference to him whom Christians honour as a God;” and then he points out that the impossibility of reconciling the dates is enough to prove that the disciple of Joshua Ben Perachia was a person altogether distinct from the Founder of Christianity.

The Rabbi Lippmann86 gives the same denial, and shows that Jesus of the Gospels was a contemporary of Hillel, whereas the Jeschu of the anecdote lived from two to three generations earlier.

The Rabbi Salman Zevi entered into the question with great care in a pamphlet, and produced ten reasons for concluding that the Jeschu of the Talmud was not the Jesus, son of Mary, of the Evangelists.87

We can see now how it was that the Jew of Celsus brought against our Lord the charge of having learned magic in Egypt. He had heard in the Rabbinic schools the anecdote of Jeschu, pupil of Jehoshua, son of Perachia, – an anecdote which could scarcely fail to be narrated to all pupils. He at once concluded that this Jeschu was the Jesus of the Christians, without troubling himself with the chronology.

In the Mischna, Tract. Sabbath, fol. 104, it is forbidden to make marks upon the skin. The Babylonish Gemara observes on this passage: “Did not the son of Stada mark the magical arts on his skin, and bring them with him out of Egypt?” This son of Stada is Jeschu, as will presently appear.

In the Mischna of Tract. Sanhedrim, fol. 43, it is ordered that he who shall be condemned to death by stoning shall be led to the place of execution with a herald going before him, who shall proclaim the name of the offender, and shall summon those who have anything to say in mitigation of the sentence to speak before the sentence is put in execution.

On this the Babylonish Gemara remarks, “There exists a tradition: On the rest-day before the Sabbath they crucified Jeschu. For forty days did the herald go before him and proclaim aloud, He is to be stoned to death because he has practised evil, and has led the Israelites astray, and provoked them to schism. Let any one who can bring evidence of his innocence come forward and speak! But as nothing was produced which could establish his innocence, he was crucified on the rest-day of the Passah (i. e. the day before the Passover).”

The Mischna of Tract. Sanhedrim, fol. 67, treats of the command in Deut. xiii. 6-11, that any Hebrew who should introduce the worship of other gods should be stoned with stones. On this the Gemara of Babylon relates that, in the city of Lydda, Jeschu was heard through a partition endeavouring to persuade a Jew to worship idols; whereupon he was brought forth and crucified on the eve of the Passover. “None of those who are condemned to death by the Law are spied upon except only those (seducers of the people). How are they dealt with? They light a candle in an inner chamber, and place spies in an outer room, who may watch and listen to him (the accused). But he does not see them. Then he whom the accused had formerly endeavoured to seduce says to him, ‘Repeat, I pray you, what you told me before in private.’ Then, should he do so, the other will say further, ‘But how shall we leave our God in heaven and serve idols?’ Now should the accused be converted and repent at this saying, it is well; but if he goes on to say, That is our affair, and so and so ought we to do, then the spies must lead him off to the house of judgment and stone him. This is what was done to the son of Stada at Lud, and they hung him up on the eve of the Passover.”88 And the Tract. Sanhedrim says, “It is related that on the eve of the Sabbath they crucified Jeschu, a herald going before him,” as has been already quoted; and then follows the comment: “Ula said, Will you not judge him to have been the son of destruction, because he is a seducer of the people? For the Merciful says (Deut. xiii. 8), Thou shalt not spare him, neither shalt thou conceal him. But I, Jesus, am heir to the kingdom. Therefore (the herald) went forth proclaiming that he was to be stoned because he had done an evil thing, and had seduced the people, and led them into schism. And (Jeschu) went forth to be stoned with stones because he had done an evil thing, and had seduced the people and led them into schism.”

The Babylonish Gemara to the Mischna of Tract. Sabbath gives the following perplexing account of the parents of Jeschu:89 “They stoned the son of Stada in Lud (Lydda), and crucified him on the eve of the Passover. This Stada's son was Pandira's son. Rabbi Chasda said Stada's husband was Pandira's master, namely Paphos, son of Jehuda. But how was Stada his mother? His (i. e. Pandira's) mother was a woman's hair-dresser. As they say in Pombeditha (the Babylonish school by the Euphrates), this one went astray (S'tath-da) from her husband.”

The Gloss or Paraphrase on this is: “Stada's son was not the son of Paphos, son of Jehuda; No. As Rabbi Chasda observed, Paphos had a servant named Pandira. Well, what has that to do with it? Tell us how it came to pass that this son was born to Stada. Well, it was on this wise. Miriam, the mother of Pandira, used to dress Stada's hair, and … Stada became a mother by Pandira, son of Miriam. As they say in Pombeditha, Stada by name and Stada by nature.”90

The obscurity of the passage arises from various causes. R. Chasda is a punster, and plays on the double meaning of “Baal” for “husband” and “master.” There is also ambiguity in the pronoun “his;” it is difficult to say to whom it always refers. The Paraphrase is late, and is a conjectural explanation of an obscure passage.

It is clear that the Jeschu of the Talmud was the son of one Stada and Pandira. But the name Pandira having the appearance of being a woman's name,91 this led to additional confusion, for some said that Pandira was his mother's name.

The late Gloss does not associate Stada with the blessed Virgin. It gives the name of Miriam or Mary to be the mother of Pandira, the father of Jeschu. The Jew of Celsus says that the mother of Jesus was a poor needlewoman, who also span for her livelihood. He probably recalled what was said of Miriam, the mother of Panthera, and grandmother of Jeschu, and applied it to St. Mary the Virgin, misled by the obscurity of the saying of Chasda, which was orally repeated in the Rabbinic schools.

The Jerusalem Gemara to Tract. Sabbath says: “The sister's son of Rabbi Jose swallowed poison, or something deadly. There came to him a man and conjured him in the name of Jeschu, son of Pandeira, and he was healed or made easy. But when he went forth it was said to him, How hast thou healed him? He answered, by using such and such words. Then he (R. Jose) said to him, It had been better for him to have died than to have heard this name. And so it was with him (i. e. the boy died).”

In another place:92 “Eleasar, the son of Damah, was bitten by a serpent. There came to him James, a man of the town of Sechania, to cure him in the name of Jeschu, son of Pandeira; but the Rabbi Ismael would not suffer it, but said, It is not permitted to thee, son of Damah. But he (James) said, Suffer me, and I will bring an argument against thee which is lawful. But he would not suffer him.”

The Gemara to Tract. Sanhedrim, fol. 43, mentions five disciples of Jeschu Ben-Stada, namely, Matthai, Nakai, Netzer, Boni and Thoda. It says: —

Jeschu had five disciples, Matthai, Nakai, Nezer and Boni, and also Thoda. They brought Matthai (to the tribunal) to pronounce sentence of death against him. He said, Shall Matthai suffer when it is written (Ps. xlii. 3), מתי When shall I come to appear before the presence of God? They replied, Shall not Matthai die when it is written, מתי When shall he die and his name perish? They produced Nakai. He said, Shall Nakai נקאי die? Is it not written, The innocent ונקי slay thou not? (Exod. xxiii. 7). They answered him, Shall not Nakai die when it is written, In the secret places does he murder the innocent? (Ps. x. 8). When they brought forth Netzer, he said unto them, Shall Netzer נצר be slain? Is it not written (Isa. xi. 1), A branch ונצר shall grow out of his roots? They replied, Shall not Netzer die because it is written (Isa. xiv. 19), Thou art cast out of thy grave like an abominable branch? They brought forth Boni בוני. He said, Shall Boni die the death when it is written (Ex. iv. 22), בני My son, my firstborn, is Israel? They replied, Shall not Boni die the death when it is written (Ex. v. 23), So I will slay thy son, thy firstborn son? They led out Thoda תודה. He said, Shall Thoda die when it is written (Ps. c. 1), A psalm לתודה of thanksgiving? They replied, Shall not Thoda die when it is written (Ps. 1. 23), “He that sacrificeth praise, he honoureth me?”

This is all that the Gemara tells us about Jeschu, son of Stada or Pandira. It behoves us now to consider whether he can have been the same person as our Lord.

That there really lived such a person as Jeschu Ben-Pandira, and that he was a disciple of the Rabbi Jehoshua Ben-Perachia, I see no reason to doubt.

That he escaped from Alexander Jannaeus with his master into Egypt, and there studied magical arts; that he returned after awhile to Judaea, and practised his necromantic arts in his own country, is also not improbable. Somewhat later the Jews were famous, or infamous, throughout the Roman world as conjurors and exorcists. Egypt was the head-quarters of magical studies.

That Jeschu, son of Pandira, was stoned to death, in accordance with the Law, for having practised magic, is also probable. The passages quoted are unanimous in stating that he was stoned for this offence. The Law decreed this as the death sorcerers were to undergo.

In the Talmud, Jeschu is first stoned and then crucified. The object of this double punishment being attributed to him is obvious. The Rabbis of the Gemara period had begun – like the Jew of Celsus – to confuse Jesus son of Mary with Jeschu the sorcerer. Their tradition told of a Jeschu who was stoned; Christian tradition, of a Jesus who was crucified. They combined the punishments and fused the persons into one. But this was done very clumsily. It is possible that more than one Jehoshua has contributed to form the story of Jeschu in the Talmud. For his mother Stada is said to have been married to Paphos, son of Jehuda. Now Paphos Ben-Jehuda is a Rabbi whose name recurs several times in the Talmud as an associate of the illustrious Rabbi Akiba, who lived after the destruction of Jerusalem, and had his school at Bene-Barah. To him the first composition of the Mischna arrangements is ascribed. As a follower of the pseudo-Messiah Barcochab, in the war of Trajan and Hadrian, he sealed a life of enthusiasm with a martyr's death, A.D. 135, at the capture of Bether. When the Jews were dispersed and forbidden to assemble, Akiba collected the Jews and continued instructing them in the Law. Paphus remonstrated with him on the risk. Akiba answered by a parable. “A fox once went to the river side, and saw the fish flying in all directions. What do you fear? asked the fox. The nets spread by the sons of men, answered the fish. Ah, my friends, said the fox, come on shore by me, and so you will escape the nets that drag the water.” A few days after, Akiba was in prison, and Paphus also. Paphus said, “Blessed art thou, Rabbi Akiba, because thou art imprisoned for the words of the Law, and woe is me who am imprisoned for matters of no importance.”93

We naturally wonder how it is that Stada, the mother of Jeschu, who was born about B.C. 120, should be represented as the wife of Paphus, son of Jehuda, who died about A.D. 150, two centuries and a half later.

It is quite possible that this Paphus lost his wife, who eloped from him with one Pandira, and became mother of a son named Jehoshua. The name of Jehoshua or Jesus is common enough.

In Gittin, Paphus is again mentioned. “There is who finds a fly in his cup, and he takes it out, and will not drink of it. And this is what did Paphus Ben-Jehuda, who kept the door shut upon his wife, and nevertheless she ran away from him.”94

Mary, the plaiter of woman's hair, occurs in Chajigah. “Rabbi Bibai, when the angel of death at one time stood before him, said to his messenger, Go, and bring hither Mary, the women's hair-dresser. And the young man went,” &c.95

According to the Toledoth Jeschu, as we shall see presently, Mary's instructor is the Rabbi Simon Ben Schetach. She is visited and questioned by the Rabbi Akiba. This visitation by Akiba is given in the Talmudic tract, Calla,96 and thence the author of the Toledoth Jeschu drew it.

“As once the Elders sat at the gate, there passed two boys before them. One uncovered his head, the other did not. Then said the Rabbi Elieser, The latter is certainly a Mamser; but the Rabbi Jehoshua97 said, He is a Ben-hannidda. Akiba said, He is both a Mamser and a Ben-hannidda. They said to him, How canst thou oppose the opinion of thy companions? He answered, I will prove what I have said. Then he went to the boy's mother, who was sitting in the market selling fruit, and said to her, My daughter, if you will tell me the truth I will promise you eternal life. She said to him, Swear to me. And he swore with his lips, but in his heart he did not ratify the oath.” Then he learned what he desired to know, and came back to his companions and told them all.98

We have here corroborative evidence that this Stada and her son Jeschu lived at the time of Akiba and Paphus, that is, after the fall of Jerusalem, in the earlier part of the second century.

I think that probably the story grew up thus:

A certain Jehoshua, in the reign of Alexander Jannaeus, went down into Egypt, and there learnt magic. He returned to Judaea, where he practised it, but was arrested at Lydda and executed by order of the Sanhedrim, by being stoned to death.

But who was this Jehoshua? Tradition was silent. However, there was a floating recollection of a Jehoshua born of one Stada, wife of Paphus, son of Jehuda, the companion of Akiba. The two Jehoshuas were confounded together. Thus stood the story when Origen wrote against Celsus in A.D. 176.

By A.D. 500 it had grown considerably. The Jew of Celsus had already fused Jesus of Nazareth with the other two Jehoshuas. This led to the Rabbis of the Gemara relating that Jehoshua was both stoned and crucified.

I do not say that this certainly is the origin of the story as it appears in the Talmud, but it bears on the face of it strong likelihood that it is. Jehoshua who went into Egypt could not have been stoned to death after the destruction of Jerusalem and the revolt of Barcochab, for then the Jews had not the power of life and death in their hands. The execution must have taken place long before; yet the Rabbis whose names appear in connection with the story – always excepting Jehoshua son of Perachia – all belong to the second century after Christ.

The solution I propose is simple, and it explains what otherwise would be inexplicable.

If it be a true solution, it proves that the Jews in A.D. 500, when the Babylonian Gemara was completed, had no traditions whatever concerning Jesus of Nazareth.

We shall see next how the confusion that originated in the Talmud grew into the monstrous romance of the Toledoth Jeschu, the Jewish counter-Gospel of the Middle Ages.

V. The Counter-Gospels

In the thirteenth century it became known among the Christians that the Jews were in possession of an anti-evangel. It was kept secret, lest the sight of it should excite tumults, spoliation and massacre. But of the fact of its existence Christians were made aware by the account of converts.

There are, in reality, two such anti-evangels, each called Toldoth Jeschu, not recensions of an earlier text, but independent collections of the stories circulating among the Jews relative to the life of our Lord.

The name of Jesus, which in Hebrew is Joshua or Jehoshua (the Lord will sanctify) is in both contracted into Jeschu by the rejection of an Ain, ישו for ישוע.

The Rabbi Elias, in his Tischbi, under the word Jeschu, says, “Because the Jews will not acknowledge him to be the Saviour, they do not call him Jeschua, but reject the Ain and call him Jeschu.” And the Rabbi Abraham Perizol, in his book Maggers Abraham, c. 59, says, “His name was Jeschua; but as Rabbi Moses, the son of Majemoun of blessed memory, has written it, and as we find it throughout the Talmud, it is written Jeschu. They have carefully left out the Ain, because he was not able to save himself.”

The Talmud in the Tract. Sanhedrim99 says, “It is not lawful to name the name of a false God.” On this account the Jews, rejecting the mission of our Saviour, refused to pronounce his name without mutilating it. By omitting the Ain, the Cabbalists were able to give a significance to the name. In its curtailed form it is composed of the letters Jod, Schin, Vau, which are taken to stand for ימח שמו וזכרונו jimmach schemo vezichrono, “His name and remembrance shall be extinguished.” This is the reason given by the Toledoth Jeschu.

Who were the authors of the books called Toledoth Jeschu, the two counter-Gospels, is not known.

Justin Martyr, who died A.D. 163, speaks of the blasphemous writings of the Jews about Jesus;100 but that they contained traditions of the life of the Saviour can hardly be believed in presence of the silence of Josephus and Justus, and the ignorance of the Jew of Celsus. Origen says in his answer, that “though innumerable lies and calumnies had been forged against the venerable Jesus, none had dared to charge him with any intemperance whatever.”101 He speaks confidently, with full assurance. If he had ever met with such a calumny, he would not have denied its existence, he would have set himself to work to refute it. Had such calumnious writings existed, Origen would have been sure to know of them. We may therefore be quite satisfied that none such existed in his time, the middle of the third century.

The Toledoth Jeschu comes before us with a flourish of trumpets from Voltaire. “Le Toledos Jeschu,” says he, “est le plus ancien écrit Juif, qui nous ait été transmis contre notre religion. C'est une vie de Jesus Christ, toute contraire à nos Saints Evangiles: elle parait être du premier siècle, et même écrite avant les evangiles.”102 A fair specimen of reckless judgment on a matter of importance, without having taken the trouble to examine the grounds on which it was made! Luther knew more of it than did Voltaire, and put it in a very different place: —

“The proud evil spirit carries on all sorts of mockery in this book. First he mocks God, the Creator of heaven and earth, and His Son Jesus Christ, as you may see for yourself, if you believe as a Christian that Christ is the Son of God. Next he mocks us, all Christendom, in that we believe in such a Son of God. Thirdly, he mocks his own fellow Jews, telling them such disgraceful, foolish, senseless affairs, as of brazen dogs and cabbage-stalks and such like, enough to make all dogs bark themselves to death, if they could understand it, at such a pack of idiotic, blustering, raging, nonsensical fools. Is not that a masterpiece of mockery which can thus mock all three at once? The fourth mockery is this, that whoever wrote it has made a fool of himself, as we, thank God, may see any day.”

Luther knew the book, and, translated it, or rather condensed it, in his “Schem Hamphoras.”103

There are two versions of the Toledoth Jeschu, differing widely from one another. The first was published by Wagenseil, of Altdorf, in 1681. The second by Huldrich at Leyden in 1705. Neither can boast of an antiquity greater than, at the outside, the twelfth century. It is difficult to say with certainty which is the earlier of the two. Probably both came into use about the same time; the second certainly in Germany, for it speaks of Worms in the German empire.

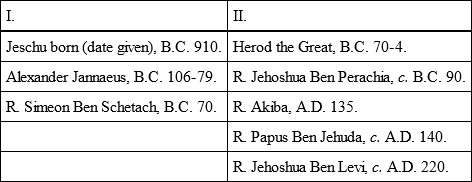

According to the first, Jeschu (Jesus) was born in the year of the world 4671 (B.C. 910), in the reign of Alexander Jannaeus (B.C. 106-79)! He was the son of Joseph Pandira and Mary, a widow's daughter, the sister of Jehoshua, who was affianced to Jochanan, disciple of Simeon Ben Schetah; and Jeschu became the pupil of the Rabbi Elchanan. Mary is of the tribe of Juda.

According to the second, Jeschu was born in the reign of Herod the Proselyte, and was the son of Mary, daughter of Calpus, and sister of Simeon, son of Calpus, by Joseph Pandira, who carried her off from her husband, Papus, son of Jehuda. Jeschu was brought up by Joshua, son of Perachia, in the days of the illustrious Rabbi Akiba! Mary is of the tribe of Benjamin.

The anachronisms of both accounts are so gross as to prove that they were drawn up at a very late date, and by Jews singularly ignorant of the chronology of their history.

In the first, Mary is affianced to Jochanan, disciple of Simeon Ben Schetah. Now Schimon or Simeon, son of Scheta, is a well-known character. He is said to have strangled eighty witches in one day, and to have been the companion of Jehudu Ben Tabai. He flourished B.C. 70.

In the second life we hear of Mary being the sister of Simeon Ben Kalpus (Chelptu). He also is a well-known Rabbi, of whom many miracles are related. He lived in the time of the Emperor Antoninus, before whom he stood as a disciple, when an old man (circ. A.D. 160).

In this also the Rabbi Akiba is introduced. Akiba died A.D. 135. Also the Rabbi Jehoshua Ben Levi. Now this Rabbi's date can also be fixed with tolerable accuracy. He was the teacher of the Rabbi Jochanan, who compiled the Jerusalem Talmud. His date is A.D. 220.

We have thus, in the two lives of Jeschu, the following personages introduced as contemporaries:

The second Toledoth Jeschu closes with, “These are the words of Jochanan Ben Zaccai;” but it is not clear whether it is intended that the book should be included in “The words of Jochanan,” or whether the reference is only to a brief sentence preceding this statement, “Therefore have they no part or lot in Israel. The Lord bless his people Israel with peace.” Jochanan Ben Zaccai was a priest and ruler of Israel for forty years, from A.D. 30 or 33 to A.D. 70 or 73. He died at Jamnia, near Jerusalem (Jabne of the Philistines), and was buried at Tiberias.

Nor are these anachronisms the only proofs of the ignorance of the composers of the two anti-evangels. In the first, on the death of King Alexander Jannaeus, the government falls into the hands of his wife Helena, who is represented as being “also called Oleina, and was the mother of King Mumbasius, afterwards called Hyrcanus, who was killed by his servant Herod.”

The wife of Alexander Jannaeus was Alexandra, not Helena; she reigned from B.C. 79 to B.C. 71. She was the mother of Hyrcanus and Aristobulus; but was quite distinct from Oleina, mother of Mumbasius, and Mumbasius was a very different person from Hyrcanus. Oleina was a queen of Adiabene in Assyria.

The first Life refers to the Talmud: “This is the same Mary who dressed and curled women's hair, mentioned several times in the Talmud.”

Both give absurd anecdotes to account for monks wearing shaven crowns; both reasons are different.

In the first Life, the Christian festivals of the Ascension “forty days after Jeschu was stoned,” that of Christmas, and the Circumcision “eight days after,” are spoken of as institutions of the Christian Church.

In the VIIIth Book of the Apostolical Constitutions, the festivals of the Nativity and the Ascension are spoken of,104 consequently they must have been kept holy from a very early age. But it was not so with the feast of the Circumcision.