Полная версия

Полная версияLost and Hostile Gospels

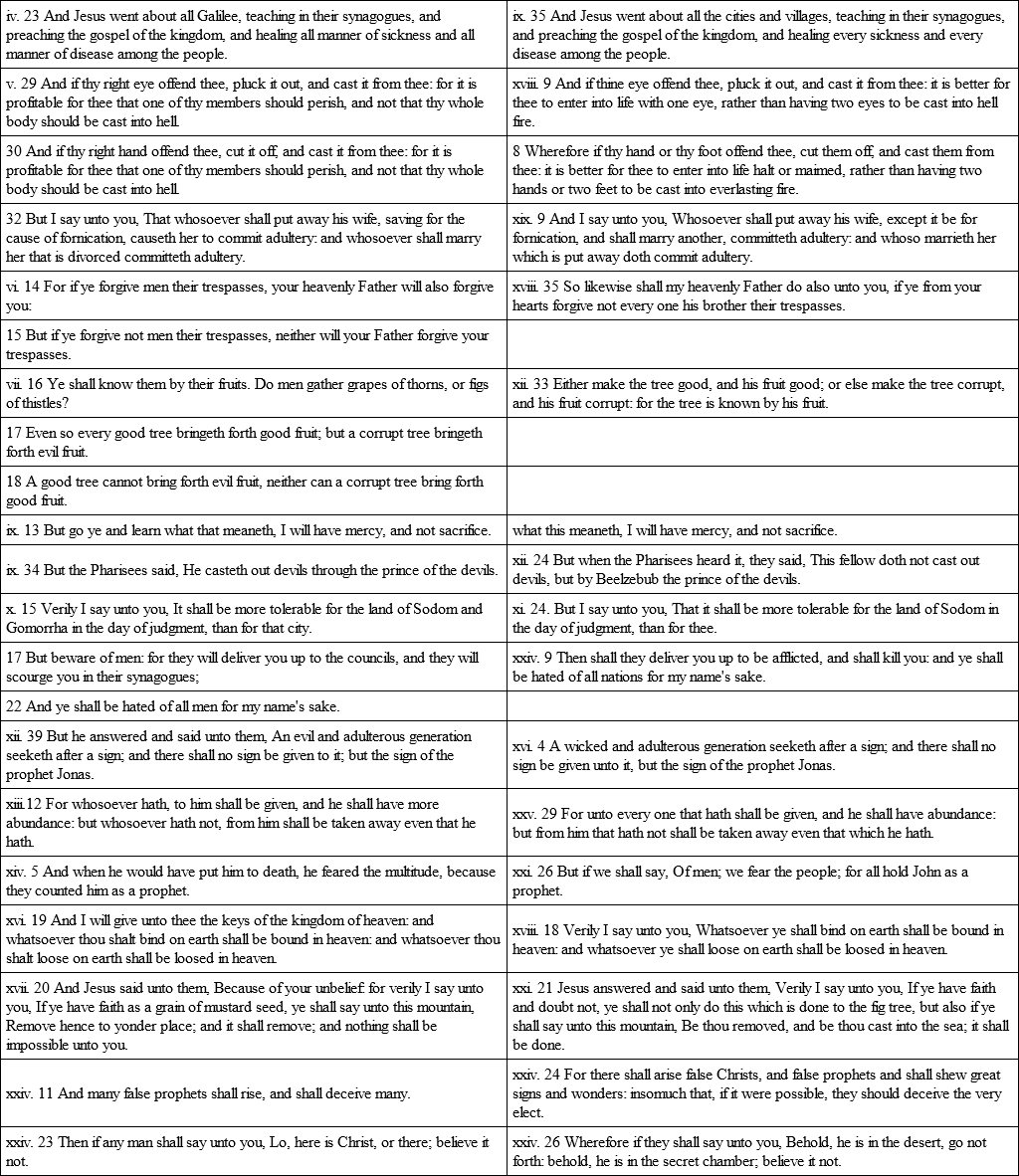

The following are parallel passages:

The existence in the first Canonical Gospel of these duplicate passages proves that the editor of it in its present form made use of materials from different sources, which he worked together into a complete whole. And these duplicate passages are the more remarkable, because, where his memory does not fail him, he takes pains to avoid repetition.

It would seem therefore plain that the compiler of St. Matthew's Gospel made use of, first, a Collection of the Sayings of the Lord, of undoubted genuineness, drawn up by St. Matthew; second, of two or more Collections of the Sayings and Doings of the Lord, also, no doubt, genuine, but not necessarily by St. Matthew.

One of these sources was made use of also by St. Mark in the composition of his Gospel.

According to the testimony of Papias:

“John the Priest said this: Mark being the interpreter of Peter, whatsoever he recorded he wrote with great accuracy, but not, however, in the order in which it was spoken or done by our Lord, for he neither heard nor followed our Lord, but, as before said, he was in company with Peter, who gave him such instruction as occasion called forth, but did not study to give a history of our Lord's discourses; wherefore Mark has not erred in anything, by writing this and that as he has remembered them; for he was carefully attentive to one thing, not to pass by anything that he heard, nor to state anything falsely in these accounts.”263

It has been often asked and disputed, whether this statement applies to the Gospel of St. Mark received by the Church into her sacred canon.

It can hardly be denied that the Canonical Gospel of Mark does answer in every particular to the description of its composition by John the Priest. John gives five characteristics to the work of Mark:

1. A striving after accuracy.264

2. Want of chronological succession in his narrative, which had rather the character of a string of anecdotes and sayings than of a biography.265

3. It was composed of records of both the sayings and the doings of Jesus.266

4. It was no syntax of sayings (σύνταξις λογίων), like the work of Matthew.267

5. It was the composition of a companion of Peter.268

These characteristic features of the work of Mark agree with the Mark Gospel, some of the special features of which are:

1. Want of order: it is made up of a string of episodes and anecdotes, and of sayings manifestly unconnected.

2. The order of events is wholly different from that in Matthew, Luke and John.

3. Both the sayings and the doings of Jesus are related in it.

4. It contains no long discourses, like the Gospel of St. Matthew, arranged in systematic order.

5. It contains many incidents which point to St. Peter as the authority for them, and recall his preaching.

To this belong – the manner in which the Gospel opens with the baptism of John, just as St. Peter's address (Acts x. 37-41) begins with that event also; the many little incidents mentioned which give token of having been related by an eye-witness, and in which the narrative of St. Matthew is deficient.269 St. Mark's Gospel is also rich in indications of the feelings of the people toward Jesus, such as an eye-witness must have observed,270 and of notices of movements of the body – small significant acts, which could not escape one present who described what he had seen.271

That the composer of St. Matthew's Gospel made use of the material out of which St. Mark compiled his, that is, of the memorabilia of St. Peter, is evident. Whole passages of St. Mark's Gospel occur word for word, or nearly so, in the Gospel of St. Matthew.272

Moreover, it is apparent that sometimes the author of St. Matthew's Gospel misunderstood the text. A few instances must suffice here.

Mark ii. 18: “And the disciples of John and of the Pharisees were fasting. And they came to him and said to him, Why do the disciples of John, and the disciples of the Pharisees, fast, and thy disciples fast not?” It is clear that it was then a fasting season, which the disciples of Jesus were not observing. The “they” who came to him does not mean “the disciples of John and of the Pharisees,” but certain other persons. Καὶ ἔρχονται is so used in St. Mark's Gospel in several places, like the French “on venait.”

But the compiler of St. Matthew's Gospel did not understand this use of the verb without a subject expressed, and he made “the disciples of John” ask the question.

Mark vi. 10: Ὅπου ἂν εἰσέλθητε εἰς οἰκίαν, ἐκεῖ μένετε ἕως ἄν ἐξέλθητε ἐκεῖθεν. That is, “Wherever (i. e. in whatsoever town or village) ye enter into a house, therein remain (i.e. in that house) till ye go away thence (i. e. from that city or village).” By leaving out the word house, Matthew loses the sense of the command (x. 11), “Into whatsoever town or village ye enter – remain in it till ye go out of it.”

Mark vii. 27, 28. The Lord answers the Syro-Phoenician woman, “Let the children first be filled: for it is not meet to take the children's bread, and to cast it unto the dogs.” The woman answers, “Yes, Lord; yet the dogs under the table eat of the children's crumbs.” The meaning is, God gives His grace and mercy first to the Jews (the children); and this must not be taken from the Jews to be given to the heathen (the dogs). True, answers the woman; but the heathen do partake of the blessings that overflow from the portion of the Jews.

But the so-called Matthew did not catch the signification, and the point is lost in his version (xv. 27). He makes the woman answer, “The dogs eat of the crumbs which fall from their masters' table.”

Mark x. 13. According to St. Mark, parents brought their children to Christ, probably with some superstitious idea, to be touched. This offended the disciples. “They rebuked those that brought them.” But Jesus was displeased, and said to the disciples, “Suffer the little children to come unto me.” And instead of fulfilling the superstitious wishes of the parents, he took the children in his arms and blessed them. But the text used by St. Matthew's compilator was probably defective at the end of verse 13, and ended, “and his disciples rebuked…” The compiler therefore completed it with αὐτοῖς instead of τοῖς προσφέρουσιν, and then misunderstood verse 14, and applied the ἄφετε differently: “Let go the children, and do not hinder them from coming to me.” In St. Mark, the disciples rebuke the parents; in St. Matthew, they rebuke the children, and intercept them on their way to Christ.

Mark xii. 8: “They slew him and cast him out,” i. e. cast out the dead body. The compiler of St. Matthew's Gospel did not see this. He could not understand how that the son was killed and then cast out of the vineyard; so he altered the order into, “They cast him out and slew him” (xxi. 38).273

Examples might be multiplied, but these must suffice. If I am not mistaken, they go far to prove that the author of St. Matthew's Gospel used the material, or some of the material, out of which St. Mark's Gospel was composed.

But there are also other proofs. The text of St. Mark has been taken into that of St. Matthew's Gospel, but not without some changes, corrections which the compiler made, thinking the words of the text in his hands were redundant, vulgar, or not sufficiently explicit.

Thus Mark i. 5: “The whole Jewish land and all they of Jerusalem,” he changed into, “Jerusalem and all Judaea.”

Mark i. 12: “The Spirit driveth,” ἐκβάλλει, he softened into “led,” ἀνήχθη.

Mark iii. 4: “He saith, Is it lawful to do good on the Sabbath-days, or to do evil?” In St. Matthew's Gospel, before performing a miracle, Christ argues the necessity of showing mercy on the Sabbath-day, and supplies what is wanting in St. Mark – the conclusion, “Wherefore it is lawful to do well on the Sabbath-days” (xii. 12).

Mark iv. 12: “That seeing they might not see, and hearing they might not hear.” This seemed harsh to the compiler of St. Matthew. It was as if unbelief and blindness were fatally imposed by God on men. He therefore alters the tenor of the passage, and attributes the blindness of the people, and their incapability of understanding, to their own grossness of heart (xiii. 14, 15).

Mark v. 37: “The ship was freighted,” in St. Matthew, is altered into, “the ship was covered” with the waves (viii. 34).

Mark vi. 9 “Money in the girdle,” changed into, “money in the girdles” (x. 9).

Mark ix. 42: “A millstone were put on his neck,” changed to, “were hung about his neck” (xviii. 6).

Mark x. 17: “Sell all thou hast;” Matt. xix. 21, “all thy possessions.”

Mark xii. 30: “He took a woman;” Matt. xxii. 25, “he married.”

But if it be evident that the author of St. Matthew's Gospel laid under contribution the material used by St. Mark, it is also clear that he did not use St. Mark's Gospel as it stands. He had the fragmentary memorabilia of which it was made up, or a large number of them, but unarranged. He sorted them and wove them in with the “Logia” written by St. Matthew, and afterwards, independently, without knowledge, probably, of what had been done by the compiler of the first Gospel, St. Mark compiled his. Thus St. Matthew's is the first Gospel in order of composition, though much of the material of St. Mark's Gospel was written and in circulation first.

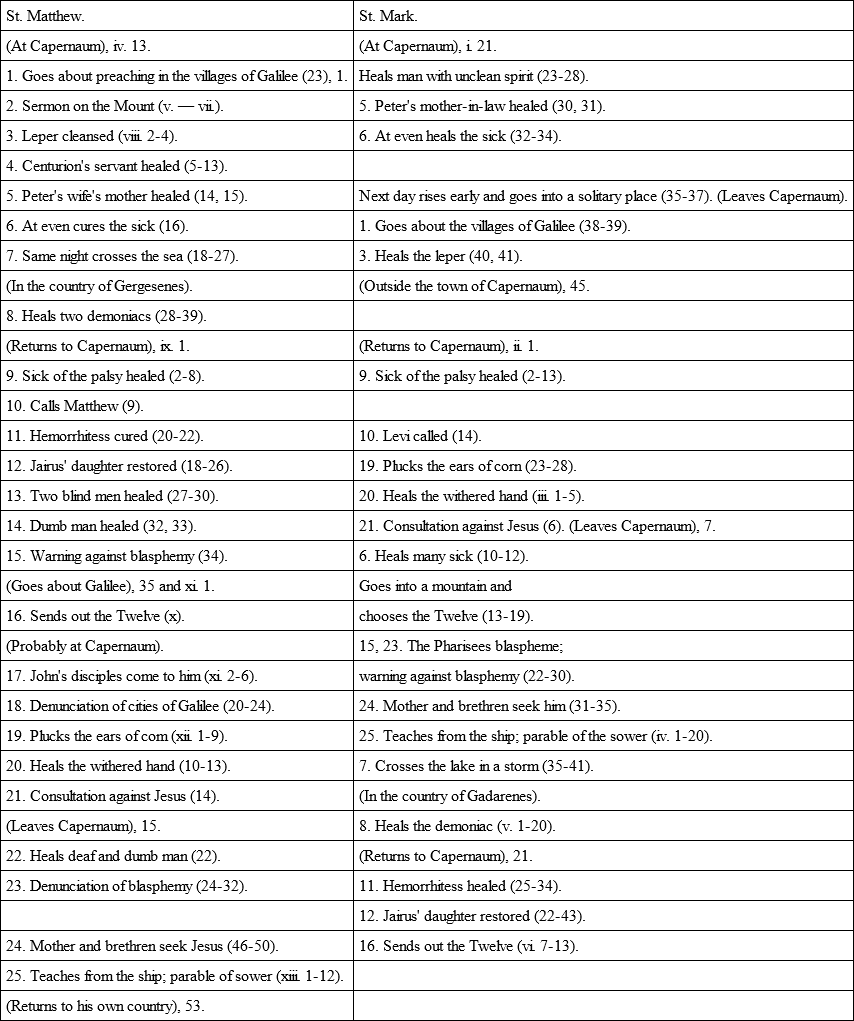

This will appear when we see how independently of one another the compiler of St. Matthew and St. Mark arrange their “memorabilia.”

It is unnecessary to do more to illustrate this than to take the contents of Matt. iv. – xiii.

According to St. Matthew, after the Sermon on the Mount, Christ heals the leper, then enters Capernaum, where he receives the prayer of the centurion, and forthwith enters into Peter's house, where he cures the mother-in-law, and the same night crosses the sea.

But according to St. Mark, Christ cast out the unclean spirit in the synagogue at Capernaum, then healed Peter's wife's mother, and, not the same night but long after, crossed the sea. On his return he went through the villages preaching, and then healed the leper.

The accounts are the same, but the order is altogether different. The deutero-Matthew must have had the material used by Mark under his eye, for he adopts it into his narrative; but he cannot have had St. Mark's Gospel, or he would not have so violently disturbed the order of events.

The compiler has been guilty of an inaccuracy in the use of “Gergesenes” instead of Gadarenes. St. Mark is right. Gadara was situated near the river Hieromax, east of the Sea of Galilee, over against Scythopolis and Tiberias, and capital of Peraea. This agrees exactly with what is said in the Gospels of the miracle performed in the “country of the Gadarenes.” The swine rushed violently down a steep place and perished in the lake. Jesus had come from the N.W. shore of the Sea to Gadara in the S.E. But the country of the Gergesenes can hardly be the same as that of the Gadarenes. Gerasa, the capital, was on the Jabbok, some days' journey distant from the lake. The deutero-Matthew was therefore ignorant of the topography of the neighbourhood whence Levi, that is Matthew, was called.

St. Mark says that Christ healed one demoniac in the synagogue of Capernaum, then crossed the lake, and healed the second in Gadara. But St. Matthew, or rather the Greek compiler of St. Matthew's Gospel, has fused these two events into one, and makes Christ heal both possessed men in the country of the Gergesenes. In like manner we have twice the healing of two blind men (ix. 27 and xx. 30), whereas the other evangelists know of only single blind men being healed on both occasions. How comes this? The compiler had two accounts of each miracle of healing the blind, slightly varying. He thought they referred to the same occasion, but to different persons, and therefore made Christ heal two men, whereas he had given sight to but one.

In the former case the compiler had not such a circumstantial account of the restoration to sound mind of the demoniac in the synagogue as St. Mark had received from St. Peter. He knew only that on the occasion of Christ's visit to the Sea of Tiberias he had recovered two men who were possessed, and so he made the healing of both take place simultaneously at the same spot.

An equally remarkable instance of the fact that St. Matthew's Gospel was made up of fragmentary “recollections” by various eye-witnesses, is that of the dumb man possessed with a devil, in ix. 32. At Capernaum, after having restored Jairus' daughter to life and healed the two blind men, the same day the dumb man is brought to him. The devil is cast out, the dumb speaks, and the Pharisees say, “He casteth out devils through the prince of the devils.”

This is exactly the same account which has been used by St. Luke (xi. 14). But in xii. 22 we have the same incident over again. There is brought unto Christ one possessed with a devil, blind and dumb; him Christ heals; whereupon the Pharisees say, “This fellow doth not cast out devils but by Beelzebub the prince of the devils.” Then follows the solemn warning against blasphemy.

It is clear that the Greek compiler of St. Matthew's Gospel must have had two independent accounts of this miracle, one with the warning against blasphemy appended to it, the other without. He gives both accounts, one as occurring at Capernaum, the other much later, after Jesus had gone about Galilee preaching, and the Pharisees had conspired against him.

St. Matthew says that after the healing of Peter's wife's mother, Jesus, that same evening, cured many sick, and in the night crossed to the country of the Gergesenes. But St. Mark says that he remained that night at Capernaum, and rose early next morning before day, and went into a solitary place. According to him, this crossing over the sea did not occur till long after.

The following table will show how remarkably discordant is the arrangement of events in the two evangels. The order of succession differs, but not the events and teaching recorded; surely a proof that both writers composed these Gospels out of similar but fragmentary accounts available to both. The following table will show this disagreement at a glance.

The order in St. Luke is again different. Jesus calls Levi, chooses the Twelve, preaches the sermon on the plain, heals the Centurion's servant, goes then from place to place preaching. Then occurs the storm on the lake, and after having healed the demoniac Jesus returns to Capernaum, cures the woman with the bloody flux, raises Jairus' daughter and sends out the Twelve.

In the Gospel of St. Mark, the parable of the sower is spoken on “the same day” on which, in the evening, Jesus crosses the lake in a storm.

In the Gospel of St. Matthew, this parable is spoken long after, on “the same day” as his mother and brethren seek him, and this is after he has been in the country of the Gadarenes, has returned to Capernaum, gone about Galilee preaching, come back again to Capernaum, but has been driven away again by the conspiracy of the Pharisees.

It would appear from an examination of the two Gospels that articles 23, 24 and 25 composed one document, for both St. Matthew and St. Mark used it as it is, in a block, only they differ as to where to build it in.

19, 20 and 21 formed another block of Apostolic Memorabilia, and was built in by the deutero-Matthew in one place and by St. Mark in another. 5 and 6, and again 9 and 10, were smaller compound recollections which the compiler of St. Matthew's Gospel and St. Mark obtained in their concrete forms. On the other hand, 3 and 16 formed recollections consisting of but one member, and are thrust into the narrative where the two compilers severally thought most suitable. We are therefore led by the comparison of the order in which events in our Lord's life are related by St. Matthew and St. Mark, to the conclusion, that the author of the first Gospel as it stands had not St. Mark's Gospel in its complete form before him when he composed his record.

We have yet another proof that this was so.

St. Matthew's Gospel is not so full in its account of some incidents in our Lord's life as is the Gospel of St. Mark.

The compiler of the first Gospel has shown throughout his work the greatest anxiety to insert every particular he could gather relating to the doings and sayings of Jesus. This has led him into introducing the same event or saying over a second time if he found more than one version of it. Had he all the material collected in St. Mark's Gospel at his disposal, he would not have omitted any of it.

But we do not find in St. Matthew's Gospel the following passages:

Mark iv. 26-29, the parable of the seed springing up, a type of the growth of the Gospel without further labour to the minister than that of spreading it abroad. The meaning of this parable is different from that in Matt. xii. 24-30, and therefore the two parables are not to be regarded as identical.

Mark viii. 22-26. By omitting the narrative of what took place at Bethsaida, an apparent gap occurs in the account of St. Matthew after xvi. 4-12. The journey across the sea leads one to expect that Christ and his disciples will land somewhere on the coast. But Matthew, without any mention of a landing at Bethsaida, translates Jesus and the apostolic band to Caesarea Philippi. But in Mark, Jesus and his disciples land at Bethsaida, and after having performed a miracle of healing there on a blind man – a miracle, the particulars of which are very full and interesting – they go on foot to Caesarea Philippi (viii. 27). That the compiler of the first Gospel should have left this incident out deliberately is not credible.

Mark ix. 38, 39. In St. Matthew's collection of the Logia of our Lord there existed probably the saying of Christ, “He that is not with me is against me” (Matt. xii. 30). St. Mark narrates the circumstances which called forth this remark. But the deutero-Matthew evidently did not know of these circumstances; he therefore leaves the saying in his record without explanation.274

Mark xii. 41-44. The beautiful story of the poor widow throwing her two mites into the treasury, and our blessed Lord's commendation of her charity, is not to be found in St. Matthew's Gospel. Is it possible that he could have omitted such an exquisite anecdote had he possessed it?

Mark xiv. 51, 52. The account of the young man following, having the linen cloth cast about his naked body, who, when caught, left the linen cloth in the hands of his captors and ran off naked – an account which so unmistakably exhibits the narrative to have been the record of some eye-witness of the scene, is omitted in St. Matthew. On this no stress, however, can be laid. The deutero-Matthew may have thought the incident too unimportant to be mentioned.

Enough has been said to show conclusively that the deutero-Matthew, if we may so term the compiler of the first Canonical Gospel, had not St. Mark's Gospel before him when he wrote his own, that he did not cut up the Gospel of Mark, and work the shreds into his own web.

Both Gospels are mosaics, composed in the same way. But the Gospel of St. Mark was composed only of the “recollections” of St. Peter, whereas that of St. Matthew was more composite. Some of the pieces which were used by Mark were used also by the deutero-Matthew. This is patent: how it was so needs explanation.

It is probable that when the apostles founded churches, their instructions on the sayings and doings of Jesus were taken down, and in the absence of the apostles were read by the president of the congregation. The Epistles which they sent were, we know, so read,275 and were handed on from one church to another.276 But what was far more precious to the early believers than any letters of the apostles about the regulation of controversies, were their recollections of the Lord, their Memorabilia, as Justin calls them. The earliest records show us the Gospels read at the celebration of the Eucharist.277 The ancient Gospels were not divided into chapters, but into the portions read on Sundays and festivals, like our “Church Services.” Thus the Peschito version in use in the Syrian churches was divided in this manner: “Fifth day of the week of the Candidates” (Matt. ix. 5-17), “For the commemoration of the Dead” (18-26), “Friday in the fifth week in the Fast” (27-38), “For the commemoration of the Holy Apostles” (36-38, x. 1-15), “For the commemoration of Martyrs” (16-33), “Lesson for the Dead” (34-42), “Oblation for the beheading of John” (xi. 1-15), “Second day in the third week of the Fast” (16-24).

To these fragmentary records St. Luke alludes when he says that “many had taken in hand to arrange in a consecutive account (ἀνατάξασθαι διήγησιν) those things which were most fully believed” amongst the faithful. These he “traced up from the beginning accurately one after another” (παρηκολουθηκότι ἄνωθεν πᾶσιν ἀκριβῶς καθεξῆς). Here we have clearly the existence of records disconnected originally, which many strung together in consecutive order, and St. Luke takes pains, as he tells us, to make this order chronological.

Some Churches had certain Memorabilia, others had a different set. That of Antioch had the recollections of St. Peter, that of Jerusalem the recollections of St. James, St. Simeon and St. Jude. St. Luke indicates the source whence he drew his account of the nativity and early years of the Lord, – the recollections of St. Mary, the Virgin Mother, communicated to him orally. He speaks of the Blessed Virgin as keeping the things that happened in her heart and pondering on them.278 Another time it is contemporaries, Mary certainly included.279 On both occasions it is in reference to events connected with our Lord's infancy. Why did he thus insist on her having taken pains to remember these things? Surely to show whence he drew his information. He narrates these events on the testimony of her word; and her word is to be relied on; for these things, he assures us, were deeply impressed on her memory.

The “Memorabilia” in use in the different Churches founded by the apostles would probably be strung together in such order as they were generally read. How early the Church began to have a regulated order of seasons, an ecclesiastical year, cannot be ascertained with certainty; but every consideration leads us to suspect that it grew up simultaneously with the constitution of the Church. With the Church of the Hebrews this was unquestionably the case. The Jews who believed had grown up under a system of fasts and festivals in regular series, and, as we know, they observed these even after they were believers in Christ. Paul, who broke with the Law in so many points, did not venture to dispense with its sacred cycle of festivals. He hasted to Jerusalem to attend the feast of Pentecost.280 At Ephesus, even, he observed it.281 St. Jerome assures us that Lent was instituted by the apostles.282 The Apostolic Constitutions order the observance of the Sabbath, the Lord's-day, Pentecost, Christmas, Epiphany, the days of the Apostles, that of St. Stephen, and the anniversaries of the Martyrs.283 Indeed, the observance of the Lord's-day, instituted probably by St. Paul, involves the principle which would include all other sacred commemorations; for if one day was to be set apart as a memorial of the resurrection, it is probable that others would be observed in memory of the nativity, the passion, the ascension, &c.

As early as there was any sort of ecclesiastical year observed, so early would the “Memorabilia” of the apostles be arranged as appropriate to these seasons. But such an arrangement would not be chronological; therefore many took in hand, as St. Luke tells us, to correct this, and he took special care to give the succession of events as they occurred, not as they were read, by obtaining information from the best sources available.

It is probable that the “Recollections” of St. Peter, written in disjointed notes by St. Mark, were in circulation through many Churches before St. Mark composed his Gospel out of them. From Antioch to Rome they were read at the celebration of the divine mysteries; and some of them, found in the Churches of Asia Minor, have been taken by St. Luke into his Gospel. Others circulating in Palestine were in the hands of the deutero-Matthew, and grafted into his compilation. But as St. Luke, St. Mark, and the composer of the first Gospel, acted independently, their chronological sequences differ. Their Gospels are three kaleidoscopic groups of the same pieces.284