Полная версия

Полная версияA Book of the Pyrenees

The frightened Crespo consented, and an hour later Gilly entered Villefranche at the head of the little army.

From Villefranche the distance is hardly five miles to Vernet, up the valley of the Riu Major. The road passes Corneilla, where there is a curious Romanesque church with a square tower and a fine marble, sculptured doorway, as also, what is a rare feature, a retable of carved marble of 1345, by an artist named Carcall de Berga. It represents incidents in the life of our Lord. At the Revolution it was pulled down, but was re-erected by an unintelligent mason, who put it together badly, as may be seen by the disorder into which the inscriptions have been thrown. The counts of Cerdagne were much attached to Corneilla, and erected here a palace, which was abandoned later and given up to the Augustinian canons.

Vernet is built in an amphitheatre of verdure, commanded by the buttresses of the Canigou. It is composed of two distinct parts, of very different aspect. The upper town is a tangle of little streets between mean, black houses with broken windows and rickety doors, above whose red tiled or slated roofs rise the church and the castle. New Vernet lies along the road lower down, and there are found the baths, the hotels, and the casino. The watering-places of Bagnères de Luchon, Cauterez, S. Sauveur, etc., are frequented only in the months of June, July, August, and rarely September; but at Vernet the season begins in April, and bathers linger on to November. For the use of winter residents a jardin d’hiver has been formed. The cold here is never great; and the salubrity of the spot has induced the erection of an open-air cure sanatorium at the height of 2250 feet, in an isolated position, for the use of consumptives.

From Vernet the ascent of the Canigou can be made on foot or by the newly-constructed cog-railway. There is a station at S. Martin de Canigou, an abbey founded at the edge of a precipice in 1007 by Count Waifre of Cerdagne, and his wife Gisella. Tradition will have it that he was engaged in warfare with the Moors, and had planned to surround them. He committed one detachment of troops to his son, with strict injunctions to delay attack till he himself should appear. But the young man, in his impetuosity, fell on the unbelievers before the arrival of the Count, and was defeated. Waifre in a rage killed him, and then repenting of what he had done, went to Rome, where the Pope required him to build and endow a monastery in expiation of his crime. This is, however, mere fable. As a matter of fact, the foundation was wholly voluntary, and Count Waifre, after having built it retired from the world within its walls, and occupied his leisure in scooping out a sarcophagus that was to contain himself eventually, which sarcophagus, now empty, is still shown. He died in 1049. The abbey, having been dismantled at the Revolution, fell into complete ruin, but has been purchased, and the church restored by Bishop du Pont of Perpignan. He has also revived the pilgrimage to it, which takes place on S. Martin’s Day (11 November), when a procession winds up the mountain from Vernet. Whether procession and pilgrims will henceforth go up in trucks by the cog-railway remains to be seen. The church is a very interesting example of earliest Romanesque, the aisles are separated from the nave by granite columns very massive, with Byzantine ornament on the capitals. Beneath the church is the crypt.

The second way to reach the roots of the Canigou, and, if it be desired, to ascend it, is to take the branch line from Elne to Arles-sur-Tech. At Le Boulou (lo Volo) the line crosses the Great Eastern highway into Spain, the main pass from Narbonne to Barcelona in Roman and medieval times, and used by Celts and Iberians before ever Narbonne and Barcelona were thought of. Le Boulou did well as a place through which travellers and merchandise streamed this way and that. But then came the days of steam; the iron road was carried along the coast from Perpignan to Barcelona, and Le Boulou’s occupation and prosperity were gone never to return.

Beyond Le Boulou we reach Ceret, famous for its bridge, a daring medieval structure, and for its nuts and cherry orchards. The architect employed on the bridge, unable to throw the bold arch over the Tech, put himself in communication with the Devil, who promised to complete it for the usual consideration. As the fatal day approached the architect became uneasy, and in the night went to the river with a sack on his back, and waited till half-past eleven. Then he let loose a cat with a kettle tied to its tail, and the Evil One, frightened at the noise, let drop the last stone needed to complete the bridge and fled. Thus the bridge never was finished; it lacks one stone to the present day. The bridge spans the river with a single arch, and the height from the key of the arch to the level of the water is 70 feet. The opening of the arch between the piers is 128 feet. It remains the boldest achievement in bridge-building accomplished in ancient France, the only other approaching it was that of Brioude, which no longer exists. This bridge was constructed in 1321. It marked the limit of the Valespir, or upper basin of the Tech.

Ceret really flourishes on hazel-nuts. The plantations extend over other communes, but Ceret is the centre of the industry. Three kinds of nuts are grown; the best is thought to be indigenous; it has a russet shell, pointed, and is contained in a cup divided into four lobes delicately striated. The taste is superior to that of the other kinds, and it is in greater request for the making of nougat. Inferior in taste, but larger, is the second variety, usually sold to be served up at dessert. The third kind is exotic, and is little cultivated.

The gathering of the nuts is done by women in the middle of August. After that the nuts have been freed from their cases, they are dried, and the sale begins in October. For the production of nougat the shells are cracked and the kernel released, and this latter is alone sent to the factories of that dainty. A hazel-nut tree will bear the third year after it has been planted, but is not calculated to render a good crop till the fifth. A hectare (2 acres, 1 r., 35 p.) is reckoned to render a crop that will bring in 130 francs.

A little over two miles above the bridge of Ceret is the Hermitage of S. Ferreolus, on the left bank of the Tech. Ferreolus was, so the story goes, a robber chieftain who committed many murders. Seized with compunction, he resolved on expiating his crimes by being rolled downhill from where now stands the chapel, in a barrel, studded internally with nails, a process the same as that which extinguished Regulus. His festival is on 18 September, on which day the chapel is visited, and there is much eating and drinking and dancing. On the following Sunday is bull-baiting.

The line passes within sight of Pallada, most picturesquely situated, at some distance from the iron road; but Pallada is best visited from Amalie des Bains.

The baths were known to and used by the Romans, but were a dependency of Arles-sur-Tech, and so remained till that needy little town in a weak moment disposed of them in 1813, and has regretted the sale ever since.

Amelie, which takes its name from Queen Amelie, occupies a specially favoured site. Mountains fold about it, it faces the sun, and is screened from every wind. The terrible Tramontane, which has bowed the olives and plane trees in Roussillon and Languedoc, is powerless to reach this blessed valley. The north-east wind indeed can steal up the ravine of the Tech, but not till it has been despoiled of its humidity, which renders it so objectionable to the inhabitants of the plain. Frost and snow rarely visit Amelie; the mean number of days when rain falls in the winter is eleven, in spring thirty-two, sixteen in the summer, and twelve in the autumn. There is a military establishment of baths at Amelie, and the place is much frequented by officers during the winter, so that it is never utterly deserted and dead, as is the generality of watering-places.

Amelie has been formed as a commune out of scraps taken from others, but mainly from Arles-sur-Tech, to which the springs originally belonged. Arles is a very curious town, vastly ancient, and is the terminus of the line. Its principal manufacture is chocolate. The little town stands on a height, and is surrounded by mountains. Arles owes its medieval revival to a Benedictine abbey of which a considerable portion remains to this day. The abbot exercised almost episcopal jurisdiction over several parishes, of which he was also temporal lord. In the sixteenth century it was in full decay, and was so poor that its finances had to be helped out by annexing to it the funds of another abbey. The reason was that it was held in commendam, the revenue eaten by a titular abbot who resided in Paris, and discharged none of his duties.

The church of the monastery was finished in 1040, and is very archaic. It underwent, however, additions in 1157, when the curious vaulting was added. As a doubt was entertained whether the piers would sustain it, they were strengthened, and smaller arches added beneath those first erected. The church reminds one of the monolithic church of S. Emillon on the Garonne. The same square, massive piers rising to a great height, quite unadorned, support the round-headed unmoulded arches. Above each arch is a small, round-headed clerestory window. The church consists of five bays, and the nave has side aisles, out of which open chapels of much later construction. There was in the church at one time a richly carved altar-piece of the fifteenth century. But when the present detestable roccoco retable was erected, this was destroyed. Some of the panels were happily preserved and affixed to the pillars in the nave.

Outside the church the western portal is early, with a triangular lintel, on which is cut a shield with A.ω between A and A. The meaning of these double A’s is not understood. In the diminutive yard without, behind is a grating, of an early sarcophagus that contained the bodies of saints Abdo and Senen. It possesses the curious property of filling with water, which can be drawn off by a tap at the side to supply bottles brought by pilgrims, who consider the water as efficacious in many maladies. How it is that the sarcophagus thus fills with water is not known; probably the clergy of the church do not themselves know, as the heavy lid has not been removed for centuries, nor the stone coffin shifted from the spot where it now stands.

But the greatest beauty of the church consists in the large cloister on the north side, of the thirteenth century. The arches are pointed, and rest on graceful pillars with dainty foliaged capitals, all of marble, and coupled. The cloister is not vaulted. This cloister was begun in 1261, but was not completed till the beginning of the fourteenth century.

The patrons of the church are SS. Abdo and Senen, Persian saints who suffered under Decius in 252. In the reign of Constantine the Great their relics were enshrined in Rome, and the marble sarcophagus that contained them still exists there, and their remains are in the church of S. Mark, Rome; but also here. Their day, 30 July, is a high festival at Arles, when the sleepy town is full of animation, and dances take place in the public square; then can be seen the red barretina and the gaily-coloured kerchiefs of the women.

Farther up the valley is a watering-place, Prats de Mollo. The name Prats, as Prades, which occurs in so many parts of the south, derives from the Latin prates, and signifies pleasant meadows by the water-side. The industry of Prats is the making of the red caps worn by the Catalans, and the rope-woven soles of spadrillos. The place enjoyed great privileges under the kings of Aragon, among these was freedom from duty on salt. Louis XIV sought to introduce it, but the people rose and slaughtered the tax-collectors. Louis sent troops to subdue them, and erected a fortress to intimidate them. On a mountain above Prats le Coral is a pilgrimage chapel containing a miraculous image of the Virgin. Crowds visit it – pilgrims from the country round, and bathers from Amelie – to see the combined devotion and jollification on 8 September.

CHAPTER XX

PERPIGNAN

County of Roussillon – Devastated by war – Tortured by the Inquisition – United to France – Given up – Removal of the Bishopric from Elne – Final annexation to France – Capital of the kingdom of Majorca – The kings – Peter IV of Aragon – Takes possession – Ruscino – Hannibal – William de Cabestang —Sirvente– Fortified by Vauban – The Puig – Place de la Loge – Carnival on Ash Wednesday – Cathedral – Altar-pieces – Nave without aisles – Indulgenced Crucifix – Other churches – Castelet – Promenade des Platanes – Dancing – Gipsy quarter – Elne – Arrangement by Hannibal – Murder of Constans – Old cathedral – Bell – Cloister – Chapel of S. Laurence – Arles-sur-Mer – The fisherfolk – Fête of S. Vincent – Salses – Poussatin – Typical Gascon – Eastern Pyrenees.

The old county of Roussillon, between Languedoc and Catalonia, formerly pertained to Spain; it was pledged to Louis XI of France by King John of Aragon along with the Cerdagne. The stipulation was that these counties should remain to France should John fail to redeem them in nine years with the sum of three hundred gold crowns, which the crafty Louis knew was a sum John could not raise. John, finding his inability to pay, stirred up the people of Roussillon to revolt against French domination, whereupon Louis poured thirty thousand men into the country, and during fifteen years it underwent all the miseries of war. Perpignan capitulated in 1475, and Roussillon remained in the hands of the French till 1493, when the feeble Charles VIII restored it, along with the Cerdagne, to the King of Aragon. At this time Aragon and Castille, united by the marriage of Ferdinand the Catholic with Isabella, formed from 1479 the kingdom of Spain.

In 1493 Ferdinand made his solemn entry into Perpignan, and brought the Inquisition in his train. The already severely tried county was further tortured by the Inquisitors, and the inhabitants were driven to desperation. They appealed to Francis I for relief, and he was induced to attempt the recovery of Roussillon, but was unsuccessful.

Under the fanatical Philip II the county was a prey to plague as well as persecution, so that hatred against Spain became intense. Philip III, sensible of this, endeavoured to cajole the citizens of Perpignan by transferring to it the seat of the bishopric from Elne, and by ennobling several of the leading citizens, but succeeded in doing no more than in forming a small Spanish faction in the town.

In 1610 all Catalonia was in revolt against Philip IV, and the county of Roussillon followed the example of Barcelona. The King of Spain sent troops to Perpignan and massacred the citizens. Those who survived the carnage appealed to Louis XIII, who sent an army into the county, and in 1642 the French, entering Perpignan, were hailed as deliverers. In 1659 the Treaty of the Pyrenees finally assured to France the possession of Roussillon and half of Cerdagne, and since then these have formed an integral portion of France.

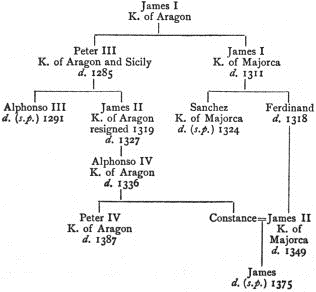

But before all this for a while Perpignan was the capital of the short-lived kingdom of Majorca. James I, King of Aragon, in 1229 had expelled the Moors from that island, and in 1238 from Valencia; and to the title King of Aragon he added those of King of Majorca and Valencia, Count of Barcelona and of Roussillon and Urgel, and Seigneur of Montpellier. To his eldest son Peter he left Aragon, and to the younger, James, he gave the rest.

James I of Majorca was succeeded by his son Sanchez, who died without issue in 1324, and the next and last king was James II, son of Ferdinand, the brother of Sanchez. James married his cousin Constance, sister of Peter IV of Aragon.

Peter was an ambitious man and insatiate in his greed. He resolved on the destruction of his cousin and brother-in-law, and the annexation of his dominions. James had made himself unpopular by his tyranny, and the islanders complained to the Aragonese king. This was precisely what Peter wanted; he summoned James to meet him in conference at Barcelona, arrested his sister Constance, and would have done the same by his brother-in-law had not James found means to escape. In the impotence of his resentment he declared war against Aragon, and thereby sealed his own fate. In 1343 Peter landed in Majorca, and was at once joined by the islanders. Then he turned his attention to Roussillon and overran it.

The unfortunate James now solicited a safe conduct, and throwing himself at the feet of the victor, implored forgiveness in consideration of kinship. He might as well have appealed to a rock. He was informed that if he would surrender Perpignan, that still held out for him, he would experience his brother-in-law’s clemency. He consented; but no sooner was Peter in possession that he declared Roussillon annexed in perpetuity to Aragon. The estates met, and offered James a miserable indemnity of 10,000 French crowns. He indignantly refused the offer. The Pope so far interfered as to obtain the release from prison of his wife Constance, and of James his eldest son. Unable to bear adversity with patience, in 1349 he sold to the French king his lordship of Montpellier, and with the money received raised 3000 foot soldiers and 300 horsemen, in the wild hope of reconquering his kingdom. With this small force he embarked, and made a descent on Majorca, but was deserted by the mercenaries when his funds gave out, and in a battle against great odds was killed, and his son James was wounded and taken prisoner. This prince had been married to Joanna I, Queen of Naples, who had murdered her first husband. Fearing to meet with the same fate, and disgusted with her levity, he had left Naples and had thrown in his lot with his father. For twelve years he languished in prison, effected his escape in 1362, and died of chagrin in 1375.

Roussillon takes its name from Ruscino, the ancient capital, which was destroyed by the Northmen in 859. The site is now occupied by a tower and a Romanesque chapel, a couple of miles from Perpignan. The name of Ruscino appears for the first time B.C. 218, when Hannibal crossed the Pyrenees on his march into Italy. The Roman Senate sent ambassadors to the people of Ruscino to urge them to oppose the progress of the great Carthaginian. They met where is now this castle, but were listened to with impatient murmurs. The tower, that dates from the twelfth century, is all that remains of the castle of the counts of Roussillon. No one has as yet undertaken serious exploration of the site, which infallibly would surrender very important relics of the ancient capital of the Rusceni, one of the Nine Peoples, and where in all probability the Phœnicians had a mercantile station; the plough, or mattock, has repeatedly turned up Iberian, Greek, Punic, Roman, and Arabic coins.

One cannot quit Castell-Rossello, as the tower is now called, without mention of William de Cabestang, who was châtelain of the neighbouring village of Cabestang. Taken with the charms of Sirmonde, the wife of Raimond, Count of Roussillon, he celebrated her in song. The husband, transported with jealousy, had him waylaid and murdered, then tore out his heart, had it roasted, and served at table. After Sirmonde had partaken of the dish he revealed to her what she had eaten. Then said she, “This meat has been to me so good and savoury that no other shall pass my lips.” The Count at this drew his sword, and Sirmonde threw herself from the window and perished by the fall. Alphonso II of Aragon went to the place, ordered the arrest of the Count, and the burial of the troubadour and the Countess before the western entrance of the church of S. Jean at Perpignan.

A few lines from one of his sirventes in her honour may be quoted: —

“Before my mind’s eye, lady fair,I see thy form, thy flowing hair,Thy face, thy iv’ry brow.My path to Paradise were sureWere love to God in me as pureAs mine to thee, I trow.“Perchance thou wilt not bend an ear,Perchance not shed for me a tear,For me, who in my prayerTo Mary Mother ever plead,To stead thee in thy hour of need,Sweet lady, passing fair.“Together from first childish days,As playfellows, I knew thy ways;I served thee when a child.Permit me but thy glove to kiss,That, that will be supremest bliss.Will still my pulses wild.”Perpignan, with its vast and huge citadel, cramped within fortifications planned by Vauban, was formerly a fortress of the first order. To-day, under changed systems of defence and attack, citadel and bastions have lost their value, and the walls and earthworks that gird the town about are now being levelled, and the moat filled to form a boulevard. When that red belt of bricks is completely demolished, Perpignan will expand in all directions.

The little river Basse divides the town into two unequal parts: the New Town, which is the ancient faubourg of the Tanneries, was included within the circuit of the fortifications by Vauban; and the Old Town, on the right bank of the river, comprises the hills of S. Jacques and de la Réal; and in this the streets are narrow and tortuous. In 1859 the medieval wall of defence along the river front was demolished and the Place Arago was made; a Palais de Justice and a Prefecture were erected on its site. The citadel is on high ground above the town, and contains the palace of the kings of Majorca. It is well to ascend the belvedere that surmounts the palace chapel to obtain a good view of the plain of Roussillon to the bald limestone range of the Corbières, to the soaring mass of Canigou, and the Pyrenean range – here called les Albères – and to the Mediterranean, blue as a peacock’s neck, and the lagoons that lie along the coast. For what Perpignan sorely lacks is a high terrace that would give a view of the surrounding country and of the mountains.

Alphonso II, King of Aragon, to whom the last Count of Roussillon bequeathed his county in 1172, did much for the place. As a considerable part of the town lay low in marshy and unhealthy ground, he desired to move it up the height, at the foot of which was a leper hospital, and which for this reason is called the Puig des Lépreux. But he met with opposition from the inhabitants, and abandoned his intention. Nevertheless the Puig became peopled by artisans, and this portion was soldered on to the Old Town, and included later within the ramparts.

The Place de la Loge is the centre of animation to the town, the forum of the capital of Roussillon. It derives its name from the Loge de la Mer, a court for naval and mercantile affairs. This dates from 1397, but was reconstructed in 1540; it is richly carved, but is somewhat weak in design, and however elaborate is the ornamentation is not effective. From the upper story is suspended a diminutive ship with all its appointments. The lower story is given up to be a café. Before this all the rollicking and fun of the carnival takes place, not, as elsewhere, on Shrove Tuesday, but on Ash Wednesday. Before this pass the fantastic cars bearing maskers representing various trades or else allegorical groups. Here goes on the battle of the dragées, when every one not masked, down to the baby in arms, wears a wire vizor over his face, such as is employed by fencers, as a protection against the dragées, which are as large as beans and as hard as pebbles.

It is somewhat startling to note the contrast presented on Ash Wednesday between the scene in the cathedral, when the whole congregation goes to the altar rails to have a cross of ashes marked on each brow, with the words: “Remember, O man, that dust thou art, and unto dust thou shalt return!” and that in the Place de la Loge in the afternoon, when fun runs fast and furious, and every one is playing the fool.

The cathedral was begun in 1324, and terminated in the beginning of the sixteenth century. Externally it promises little, but the interior is overwhelmingly beautiful. The church is built of tiles rather than bricks, each 17 inches long by 1½ inches thick and 8 inches wide; with bands of these tiles alternate belts of cobble-stones arranged in herring-bone fashion.

The interior consists of one vast nave 56 feet wide, in seven bays and with transepts. The whole ends in a magnificent apse. Between the buttresses are chapels, 17 feet deep, in each of which is a three-light window most of these blocked by retables, and this renders the church unnecessarily dark. The high altar-piece of white marble, of the seventeenth century, is an admirable composition, purely Renaissance in character, executed by Bartholomew Soler, of Barcelona. In the niches are statues of the Virgin, S. John, and SS. Julia and Eulalia, patronesses of Elne. Particularly noticeable is a superb carved oak and gilded reredos in the north transept, of the fifteenth century, representing scenes of the Passion in eight compartments. Another, enclosing fine paintings in place of sculpture, is in the south transept. The huge organ-case is a splendid bit of work of the sixteenth century.