Полная версия

Полная версияA Book of the Pyrenees

Arreau stands at the junction of the two rivers called Neste, and also where the Lastie enters the stream. It has a cheerful appearance. The church of Notre Dame is of the fifteenth century, castellated, with additions a century later, built on the foundations of a church of the twelfth century, of which a good doorway remains. The chapel of S. Exuperius is of the eleventh century, and has a Romanesque portal. It stands above the Neste of Aure. The mairie is over the wooden market-hall. The entrance to the valley of the Neste de Luron is through a ravine with precipitous sides. Presently it opens out and reveals the little bourg of Bordères, commanded by the ruined castle of the Armagnacs. For now we are in Armagnac territory, and with this castle is connected the story of the last of that evil and ill-omened race. Michelet says of them: —

“Frenchmen and princes as they were become, their diabolical nature broke out on every occasion. One of them married his brother’s wife, so as to be able to retain the dower, another married his own sister, by means of a false dispensation. Bernard VII, Count of Armagnac, who was almost king, and ended so ill, had begun by despoiling his kinsman, the Viscount of Frézenzaguet, flinging him into a cistern, along with his sons, his eyes plucked out. This same Bernard, pretending to be a servant of the Duke of Orléans, made war against the English, but only worked for his own ends, for when the Duke came into Guyenne he made no attempt to assist him. But no sooner was that prince dead than he posed as his avenger, brought up all the South to ravage the North, made the young Duke of Orléans marry his daughter, and gave her as dower his bands of robbers, and the malediction of France.

“What made these Armagnacs specially execrable was their impious levity allied to their innate ferocity.”

The Armagnac territory extended as a strip from the Garonne to the Pyrenees. It was a fertile and well-peopled land; its principal towns were Auche, Mirande, Vic, and Lectoure.

The Armagnac family derived from a Garcias Sanchez, Duke of Gascony in the early part of the tenth century. He was nicknamed the Hunchback, and he seems to have bequeathed a moral distortion to his descendants.

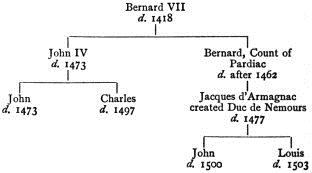

John IV, Count of Armagnac, was especially associated with the castle at Bordères; and his story must now be told.

This headstrong man fell in love with his own sister, Isabella, and failing in his application to Rome for a dispensation to allow him to marry her, he forged one, and presented it to the chaplain of the castle, and demanded that he should unite them. When the priest demurred, Count John threatened to throw him headlong from the window into the river unless he obeyed. When others remonstrated, he drew his dagger on them. The cowed chaplain submitted to celebrate the incestuous nuptials.

The Pope now excommunicated the Count, and King Charles VII vainly endeavoured to recall him to a better mind; but Armagnac resisted kind instances, and defied force. Soon after he associated himself with the insurrection of the Dauphin. The Duke of Clermont was sent against him. His guilty passion had enfeebled the mind of John, and in place of resisting the invasion, he abandoned his dominions, and fled with Isabella to the protection of his relative, the King of Aragon. He was summoned by the Parliament, and having been rash enough to appear, was arrested and imprisoned. Soon after he managed to escape. The sentence of perpetual banishment was passed upon him, and his dominions were forfeited. The Valley of Aure was, however, exempted so far that it was granted as a dowry to his sister.

Then, as his last place of refuge, he retired to the Castle of Bordères, in the depths of the mountains. The once powerful and haughty Count of Armagnac was reduced to the deepest destitution, shunned by all, shrunk from even by his own subjects in the valley of the Neste, as though he were a leper or a Cagot. At last, impelled by his necessities rather than moved by remorse, he begged his way to Rome to obtain absolution for himself and for his sister. This was granted, but on hard conditions for himself, and that Isabella should retire into a convent at Barcelona.

At this time Louis XI ascended the throne of France, and by him the Count of Armagnac was restored to his former rank and possessions. He now married Jeanne, daughter of the Count of Foix, and the past was forgotten, or at least forgiven.

But this restless man, incapable of feeling gratitude for favours, allied himself with the enemies of the King, Charles the Bold, the Duke of Guyenne, and the King of England.

Louis XI took occasion of the first moment of tranquillity allowed him by the ambitious projects of the Duke of Burgundy, to chastise John of Armagnac. In 1473 he confided the task to the Cardinal of Albi, who besieged him in Lectoure. The town, which was strongly fortified, defended itself bravely. Proposals of surrender were made to the Count, but whilst negotiations were in progress, one of the gates was forced, and John’s son, of the same name as his father, was killed fighting in the streets. John IV of Armagnac was stabbed in the presence of his wife, who was pregnant at the time. By order of Louis XI, who had no desire to see the line of Armagnac continued, she was thrown into prison and poisoned.

The title and claim to the county now devolved on Charles, another son of John IV; but Louis XI had him cast into prison, and retained there till he died of chagrin. There existed at the time another branch of the family, that had likewise received favours from King Louis, and had repaid them with treachery. Jacques d’Armagnac had been given by Louis XI vast estates in Meaux, Châlons, Langres, and Sens. The king had married Jacques to Louise of Anjou, and had created him Duke of Nemours. But Jacques was false to his benefactor, and joined in the League of Public Good against him. At the Treaty of Conflans he returned to his allegiance, swore fidelity on the relics in the Sainte Chapelle, and had the governorship of Paris conferred upon him. The very next year, 1469, he went over to the enemies of the King, and sided with his cousin, John IV, entering with him into negotiations with the English. But alarmed at the fate that befell John, he solicited pardon, and took an oath of fidelity, the most solemn and binding that could be devised.

Two years later, when Louis XI was in embarrassment, the Duke refused the King the succour he demanded, and prepared to lay his hands on Languedoc. No sooner was Louis delivered from his anxieties than he besieged and took Nemours, in his Castle of Carlat, and confined him in an iron cage in the Bastille. His wife, feeling confident that he would experience no mercy at the hands of the justly incensed King, died during her confinement at Carlat.

Jacques d’Armagnac’s hair turned white within a few days. He was not mistaken about the gravity of his position. Louis was alarmed at these incessant conspiracies, and indignant at the ingratitude of the Duke, whom no oaths could bind. In vain did Nemours implore permission to speak with the King face to face; Louis refused to see him, and gave orders that he should be tortured. One day, hearing that the prisoner had been treated with some consideration, he wrote sharply to the gaoler, “Give him Hell (the extremity of torture); let him suffer Hell in his own chamber. Take care not to let him out of the cage except to be tortured.” Jacques d’Armagnac was executed on 10 July, 1477. The assertion often made, that by the order of the King his children were placed under the scaffold so that their father’s blood might fall over them, is asserted by no contemporary writers. His sons died without issue, and so ended this wicked family.

For some way above Bordères the Neste of Luron traverses a gloomy ravine; but then all at once it opens out and we come on a basin well cultivated, fringed with woods, and studded with twelve villages, about their church spires. The road ascends steeply past slate quarries that send down their avalanches of grey refuse over the base of the hill surmounted by the donjon of Gélos. It is still a long way on to the Lac de Caillaouas, that lies at the height of 3500 feet, and covers 120 acres; its blue waters are fed by some small tarns higher up under the glaciers of the Gourgs Blancs. This is one of the scenes of most savage grandeur in the Pyrenees. The lake is of great depth, and swarms with trout. A tunnel has been driven fifty-five feet below the surface through the rock that retains the lake, and through this the water can be drawn off to supply the deficiencies in the Neste and the canal that leads from it in time of drought. The work was completed in 1848.

The other Neste, that of Aure, is of even more economic importance. It rises under the Pic de Campbieil, 9550 feet; but receives a large influx of water from the Neste de Couplan that is supplied from a whole series of lakes, the largest of which is Orredon.

Above Arreau is Cadéac, one of the most ancient sites in the valley. Hither came the representatives of the various communes of the valley of the Neste to discuss their affairs, and decide their policy; for here, as in Lavedan, the people enjoyed great liberties, of which the Armagnacs did not care to deprive them. Cadéac occupies a hill surmounted by a feudal tower of the twelfth century. The church has an early north doorway, and sculptures let into the walls. The road passes up the valley under the porch of a chapel, Notre Dame de Penetaillade, that has a curious fresco representing the death of the Virgin on the façade. Vielle Aure is a village lying on both sides of the river, with a church of the twelfth century, and is an excellent centre for excursions. The road then crosses the river and reaches Bourespe, with a church of the fifteenth century, but a much earlier tower. In the porch are curious paintings of the date 1592, with representations of the deadly sins as ladies (why as ladies, and not as men?), in the costume of the period, mounted on strange beasts, and carrying behind them demons with hideous faces on their stomachs and breasts. Pride is riding on a lion, Avarice on a wolf, Gluttony on a pig, Luxury on a goat, Anger on a horse, and Idleness on an ass.

Surely Gluttony, Avarice, Anger are traits of man’s intemperate passions rather than of woman’s humours. Vitium is neuter, it will serve for either or none. But it is the old story of the sculptor and the lion. He showed the King of the Beasts a group finely carved that represented a man slaying a lion. “Ah,” said the royal beast, “if a lion had been the sculptor, the figures in the group would have been in reversed positions.”

It was men, not women, who wrought these representations of the cardinal vices.

Tramesaïgues (between the waters) occupies a rock, the road passes below it.

The cluster of lakes in the Néouville basin of mountains have been taken in hand as well as the Lac de Caillaouas. The undertaking was difficult, as work was possible there for only three months in the summer; all the rest of the year the basin in which they lie is buried in snow, and some of the tarns remain hard frozen. The largest of the lakes is Orredon, lying 5600 feet above the sea; it is the lowest of all, and receives the waters of the Lac d’Aubert and the Lac Aumar, lying in one valley, separated by a gravelly ridge of glacial rubbish; the Lac de Cap-de-Long reposes in another. The works were begun in 1901 and terminated in 1905.

The Four Valleys – Magonac, Neste, Aure, and La Baronne – formed another of those confederate republics of which there existed so many in the Pyrenees. Of these Magonac, with its chief town Castelnau, lay to the north of Lannemezan, and was not properly a valley at all.

After the extinction of the Armagnacs, the overlordship passed to the kings of France, and each and all from Louis XII to Louis XVI had to recognize and allow their very extended privileges. From the year 1300 no seigneur could withdraw an inhabitant of the Four Valleys from the jurisdiction of their own judges; every citizen could own land, marry, create an industry, or carry on any trade without authorization. The right to bear arms belonged to every one; and up to the eve of the Revolution the Four Valleys were exempt from all war-tax and from the obligation to have troops quartered on them.

La Fayette had no occasion to have gone to America to have seen what republican self-government was. It existed at his doors.

CHAPTER XV

LUCHON

Montréjeau – A bastide – Grotto de Gargas – A cannibal – Blaise Ferrage – Taken and escapes – Final capture – Execution – S. Bertrand de Cominges – Sertorius – Gundowald – His coronation – Treachery of Boso – And of Mummolus – Murder of Gundowald – Destruction of the city – Bishops at Valcabrères – Church of S. Juste – Bertrand de l’Isle-Jourdain rebuilds the town – Bertrand de Got – Jubilee – The cathedral – Nonresident bishops – Counts of Cominges – Murder of a boy husband – Imprisonment of the Countess Margaret – Bequeaths the county to the Crown of France – The Garonne-Bagnères de Luchon – Its visitors – Its antiquity – Lac de Seculéjo – Description by Inglis – Cures for all disorders —Le Maudit– S. Aventin and the bear – Val de Lys – Val d’Aran – S. Béat and its quarries – The valley should belong to France – Viella – The Maladetta – Trou de Toro – Port de Venasque.

At Montréjeau the line branches off to Bagnères de Luchon from the trunk to Toulouse. Montréjeau was Montroyal, then Montreal, and then what it has now become through deformation by the Gascon tongue. It was a bastide, one of those artificial towns, created first by Edward I, and then copied by great nobles, and by the kings of France, in which every street was either parallel to another, or cut it at right angles; and the houses were built in blocks, the whole surrounded by walls, and the church usually serving as part of the fortification.

Montréjeau was the capital of the Marquesate of Montespan. The site is beautiful; and from the terrace, in clear weather, the giants of the Pyrenees are seen to stand up due south, and the chain stretches away into the vaporous distance, east and west. The church has a huge octagonal tower that served as keep to the fortress. The town stands a little away from the station, to its disadvantage. From it visitors usually start to see the Grotte de Gargas, the finest in the Pyrenees; it might be visited equally well from S. Bertrand de Cominges, but that no carriage can be obtained in that decayed city. The train, moreover, halts at Aventignan, the station next before reaching Montréjeau, to allow of a visit to the grotto. The floor bristles with stalagmites, and the stalactites from the roof have in several places united with the stalagmites below. The strangest forms have been assumed by the calcareous deposits, and the custodian points out an organ front, a cascade, a bear, an altar, and the bed of the savage. A spring rises in the cave. Excavations made in the floor have exposed two beds of palæontological deposits of different epochs: human bones, flint tools, and bones of long extinct animals.

The discovery of this grotto is due to a series of ghastly crimes committed just ten years before the outbreak of the French Revolution.

A panic terror pervaded the neighbourhood. Among the rocks, somewhere, none knew exactly where, a monster had his lair, fell upon those who travelled along the roads, robbed them, maltreated them, carried them off, and devoured them. And this monster was a man. In 1780 the Parliament of Languedoc was called upon to try and sentence the cannibal, who was actuated by no other motive than a ravening appetite for human flesh.

Soon after the first disappearance of his victims every one had come to the conclusion as to who he was. He was Blaise Ferrage, commonly known as Seyé, a native of Ceseau, born in 1757. He was a small man, broad-shouldered, with unusually long arms, and was possessed of extraordinary strength. By trade he was a stonemason, and had worked at his trade till aged twenty-two. What induced him, in 1779, to throw up his work, quit his home and human society, in order to abandon himself in solitude to his wolfish appetite for blood, is not known; whether it was originally due to his having committed some criminal act that impelled him to fly to the rocks for refuge was never ascertained.

High up in a limestone cliff he discovered a cavern, the entrance to which was at that time so small that it had to be passed through on all fours. But within it was spacious, and provided with a running stream.

After he had spent the day in sleep Blaise would descend in the twilight and ramble over the country through fields and gardens, and appropriate to his use what he listed – fruit, fowls, sheep, pigs – and bear them away in the darkness of night to his den. Luck favoured and emboldened him, and his ferocity increased. He delayed his return till dawn. Lurking behind a wall or a bush he watched for milkmaids who were so unfortunate as to come in his way. There was no escaping him, for he carried a gun and was a sure shot. When he pounced upon his prey he tore it to pieces, or else carried it alive to his lair, and the shrieks could be heard from afar, paralyzing the timorous peasantry with fear.

His name was a terror to all the country round. In the evenings the spinners about the fire, the topers at the tavern, spoke only of the werewolf. It was thought that his tread could be heard at night among the withered leaves of autumn; that his panting breath was audible about the doors; that his gleaming eyes pierced the fog. Men pictured him lying on a ledge of rock half the day peering into the valley, motionless, watching for and selecting his prey. Imagination figured what the life must be of this man converted into a wild beast, who had renounced the society of his fellows to live among the rocks and tread the snow-fields, hearing naught save the howl of the wind, the cry of the birds of prey, and the baying of the wolves. As no single person who had disappeared ever returned, as no bodies were ever found, it was concluded that he was a man-eater.

Men he shot, strangled, or stabbed, and dragged their carcases to his lair. But he preferred to fall on women, especially such as were young; but the choicest morsels he selected were little children. On one occasion he fell short of powder and shot, and had the temerity to descend in full daylight, and in market time, to Montégu. He was recognized, and immediately the market people fled from him right and left; the dealers deserted their stalls, and the would-be purchasers hastened to take refuge within doors. He leisurely possessed himself of what he required and sauntered out of the place, not a man venturing to stay him.

At last the officers of justice seized him, and conveyed him to prison. But he broke loose the same night, and again disappeared among the mountains. The peasants were convinced that he had a talisman concealed in his hair, which enabled him to break the strongest chain and to open every lock.

He was again secured, and this time his hair was cut and searched for the supposed talisman there concealed, but, of course, ineffectually. He again, nevertheless, effected his escape.

Fear of him now passed all bounds. Girls and grown women, even the strongest men no longer ventured abroad after dark, not so much as to cross the street.

Then occurred two acts of violence which stirred the magistrates to greater activity.

Ferrage entertained a suspicion that a certain landowner in the district had instigated the police to track him. He set fire to this man’s barns, stables, and cowsheds; and most of the cattle and all his grain were consumed in the flames. The other case was that of a Spanish muleteer who was driving his beasts over the mountains of Aure. Ferrage associated himself with the man on the way, volunteered to act as his guide, and the muleteer was never seen again.

High rewards were offered for the apprehension of Blaise Ferrage, but no dweller in the district dared attempt to earn it. Moreover, to track and arrest the cannibal was not a light matter. None knew precisely where he concealed himself, and it was certain that he would send a bullet into the first man whom he saw approach his place of refuge and concealment.

Finally he was taken, but only by subtlety. There was a fellow who had been guilty of more than one crime, and whom the officers of justice desired to secure. In order to make his peace with them, this man offered to assist in capturing Blaise, if he were assured of a free pardon and a reward. This was promised. Accordingly he climbed the rocks, yelling out the name of Seyé, by which Ferrage was commonly known, and crying for help. The cannibal cautiously thrust his head out of his cave, and seeing the man fleeing as for his life beckoned him to approach. The refugee breathlessly told him that he was flying from justice, that he had broken out of prison, and entreated to be sheltered. Ferrage took him in, and the fellow gained Blaise’s confidence. He lived with him for awhile in his cave. However solitary a man may be, he yet craves for the society of a companion, and Blaise and this man became intimate. They went together on predatory excursions, and the betrayer finally lured Ferrage into an ambuscade laid for him, where he was taken, and firmly secured by a body of police. He was led to prison and kept there strongly guarded. The whole country breathed with relief when it was known that he was in chains and behind strong bars.

The trial was expedited and short. For three years this monster had terrorized the countryside. The number of charges of robbery and murder brought against him were innumerable.

On 12 December, 1782, the Parliament of Languedoc sentenced him to be broken on the wheel. He was then aged twenty-five. On the following 13th December Ferrage was executed. The sentence was carried out in the following manner. The culprit was fastened to a cart wheel, his limbs twined in and out among the spokes. The executioner smote with an iron bar on the limbs and broke them, one by one. Then came the coup de grâce, given across the chest.

It was estimated that he had murdered and eaten eighty persons, the majority of these were women and children. When he was executed crowds attended, palpitating with alarm, for they expected that at the last moment he would burst away and resume his murderous career.

He walked to death with florid countenance and with seeming indifference to his fate. Whether the prison chaplain induced him to express remorse for his guilt is not known. Only when the mangled body was cast down from the wheel, and consigned for burial to the grave-digger, did the crowd feel satisfied that they were relieved from a nightmare of horrors.

A little way above the station of Montréjeau the two great Pyrenean torrents of the Neste and the Garonne unite their waters and flow towards the east. The line to Luchon does not follow the Garonne, that issues from a gorge, but crosses it farther up at Barbazan, in a broad basin studded with villages set in luxuriant verdure.

On an isolated hill, an outlier of the Pyrenees, rises a lofty and beautiful church, with houses grouped about it; apparently a stately medieval city, actually a poor village of less than four hundred inhabitants. This is S. Bertrand de Cominges. At one time it was as splendid a town as any in Gaul, and was the capital of an important people, containing from 30,000 to 50,000 souls. These could not all be accommodated on the rock, and the town flowed down the side into the plain, where now stands Valcabrères, the Vale of Goats. S. Bertrand de Cominges is one of the few towns in France of whose foundation we know the precise date.

Sertorius was one of the most extraordinary men in the later times of the Roman Republic. He was a native of Nursia, a Sabine village, born of obscure but respectable parents, and a devoted son to his widowed mother. In B.C. 83 Sertorius went to Spain to organize a national revolt against the intolerable oppression of Rome. Availing himself of the superstitious character of the people, he tamed a fawn, so that it accompanied him in his walks, lived in his tent, and was regarded by the Iberians as a tutellary spirit that communicated to him the will of the gods.

He maintained a stubborn resistance against the power of Rome for many years, defeating army after army. In B.C. 77 Pompey was appointed by the Senate to command in Spain, along with Metellus. Sertorius, at first, defeated both. Pompey was obliged to appeal to the Senate for men and arms. Unless supported efficaciously, he declared that he must infallibly be driven out of Spain. At length the tide of success turned. Disaffection broke out among the troops led by Sertorius, and a conspiracy was formed to destroy him among some of his most trusted comrades. One of these invited him to a banquet, at which they endeavoured to provoke him to anger and make an excuse for a fray by the employment of obscene language, which they were well aware that he detested; then by grotesque and undignified capers, as if they were drunk. Sertorius turned on his couch so as not to see their buffoonery, when they rushed on him with their daggers and slew him, B.C. 72. His faithful adherents fled through the defiles, and over the passes of the Pyrenees, and settled in the district afterwards known as the land of the Convenæ, and built Lugdunum Convenarum as their capital in that same year, B.C. 72.