Полная версия:

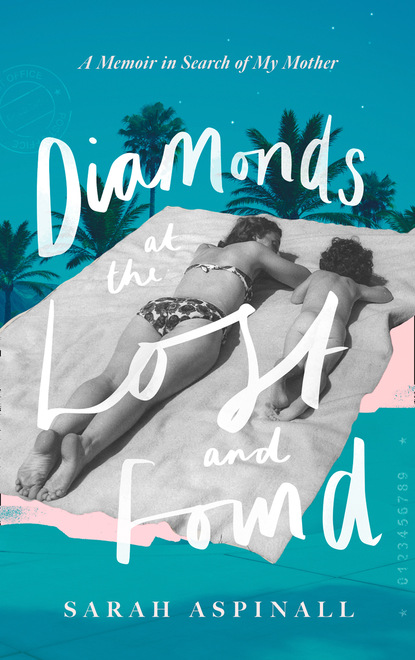

Diamonds at the Lost and Found

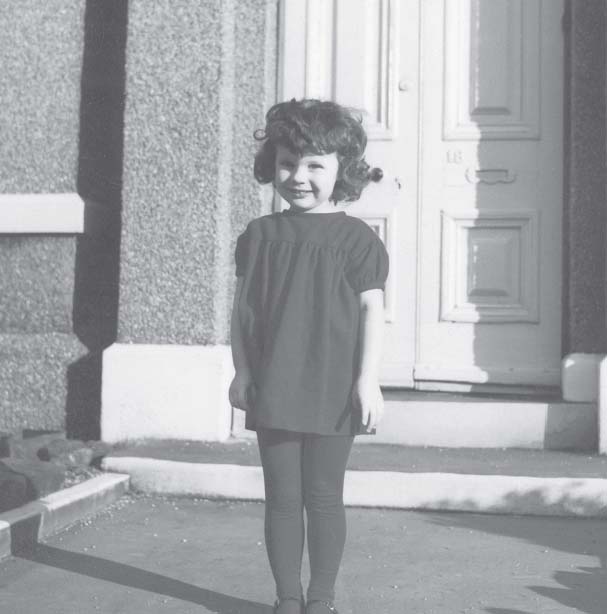

Me, 1961.

The landing felt like a scary place, as across from Daddy’s door was Nana’s room, and from behind it came sounds of moaning and yelling. Nana was always either in bed or in her deep armchair, shaking and confused from her worsening Parkinson’s. Often I was sent in by my mother to clear the ghost people that were upsetting her. Nana would wave and shout at these people that I couldn’t see, but after I’d shooed them out and told her that they were now ‘all gone’ she would lie back with a sigh of relief. It was my special job and I did it as thoroughly as I could. But she’d then doze off and wake to find the ‘people’ had come back to torment her, and so the cycle would begin again. It was a house of sickness, and no wonder my mother wanted to get away from it whenever she could.

4

The Riviera of the North West

THE BEST PART OF THE DAY was spent sitting in the gorgeousness of Marshall and Snelgrove’s restaurant with my mother, eating a banana split while the orchestra played, the violin mingling with the soft buzz of adult chatter. Elegant model girls in their gowns approached each table, delicately holding placards with the price, always in guineas, and they would do a pretty twirl to show off the dress to all its advantage.

Auntie Ava would often be with us, and she and Mummy would talk to them about the ‘cut’ of the gown and discuss the style and colour. I loved the words they used. ‘Would you say that was fuchsia or mauve?’ ‘The silk mohair has a lovely sheen, and don’t you love the dear little sweetheart neckline?’ The model smilingly chatted with them, as they fingered the delicious fabrics.

I’m not sure when it was that I first heard one or two of these young women described as Mummy’s ‘girls’. Was it overheard, or was it ever whispered to me gently, some kindly hand on my arm somewhere out of the softness, across the plush dreaminess of the afternoon?

What did it mean, that in some curious way these beautiful creatures, along with a girl who worked in the make-up department, were connected with my mother? This fed the slight unreality that I sometimes sensed my mother floated in, and me with her; but in the respectable elegance of Marshall’s restaurant the willowy young women simply appeared to be queenly creatures.

But then I would slip off away from them to explore, and feel that exhilarating thrill of freedom and excitement with the huge department store as my territory.

I’d begun to have dreams, that would recur for the rest of my life, of discovering a door in a house that I’ve lived in for some time, a house that has become my home, and yet there is a door I’ve never noticed before, until quite suddenly it opens into a new world that is all mine: it may be a glittering ballroom with great doors onto a maze of walled gardens with fountains where people greet me as if they know me, or a palm house with an intricate webbing of glass and cast-iron tracery soaring above me with all kinds of strange plants thronged with colourful birds and people gathered in its secret corners. My excitement was always intense at these discoveries and it began then, during my forays into these old shops and hotels off Lord Street, as if from them there arose ghosts from a different age.

I began to see that the immediate world beyond that unhappy house, Southport itself, was full of promise. What had been such a wonderland for Audrey, as a child, became one for me now, and Marshall and Snelgrove department store and the Prince of Wales Hotel were its great pleasure palaces, full of endless possibilities for exploring. In my own head this was who I was: ‘an explorer’.

Some of my forays and adventures would take place while my mother was with Auntie Ava, her only friend. Ava was, by common agreement, the most beautiful woman in Southport. She looked and dressed like a nineteen forties movie star, and still wore in the more casual decade of the 1960s what my mother called ‘picture hats’, with a wide brim to frame her chocolate eyes and moon-pale skin. She spent a lot of time in bed, and was seen by people as a little ‘odd’. She could be funny, and even astute, but she had an air of childlike naivety and seemed to be incapable of doing the simplest of things. It was therefore hard to judge whether she was unaware of, or chose to ignore, my mother’s unusual lifestyle.

Ava’s husband, Anthony, with his cravats and immaculate blazers had the suave looks of a matinee idol. He didn’t go to work and loathed my mother, for taking Ava away from him for so much of the day. He also feared that Ava’s friendship could affect their own reputation, which he cared about enormously.

Anthony and Ava sat every summer’s day on a kind of stage set outside their house. They’d had the brick wall in their front garden specially lowered so that the whole town could see them there, on their elaborate patio adorned with beautiful furniture and parasols, dressed as if for Ascot, but simply taking afternoon tea brought out by the housekeeper. Buses went past and people pointed; they were famous locally for their gracious, old-fashioned appearance and general eccentricity.

Perhaps it was Ava’s oddness that inured her, or maybe attracted her, as a fellow outsider, to my mother’s outcast status. For Audrey was increasingly ostracized by the town and this exclusion soon extended to Ava for being my mother’s close friend.

During the times when my mother was in Southport their routine was always the same. Ava would spend the morning getting ready for Audrey to collect her at eleven for morning coffee at Marshall’s. After my own treat of an ice cream or teacake, I would be sent off to play. I had several favourite routines. One was to visit the make-up counters where the attractive ladies would let me try on perfume and put lipstick on me. Another trick was to goad the lift man; he seemed to dislike children, and would be mean and pompous if I rode up and down between floors with no purpose. My favourite pastime of all was to visit the manager.

This involved getting past his fierce secretary who sat behind a desk outside his office clacking away at a big black typewriter which pinged occasionally. I would stand politely before her, asking ‘Could I please, please say hello to the manager?’ Sometimes she would just say no, and that he was very busy, but sometimes she would say that she would ask him, although she expected he was very busy. Usually the answer came back that I could go in, but just for two minutes, as he was really very busy. The manager, Mr Naylor, sat in a wood-panelled office behind a large desk. The routine was always the same.

‘And what can I do for you today, young lady?’ he would ask.

‘Please can you make a swan for me?’ I would beg.

He would then take a packet of cigarettes from his drawer, pull out the silver paper, and twist it into a delicate swan shape which he would present to me with a flourish. The charm lay in my knowing that this busy man had set aside a few minutes of his day for me, and also in the lovely masculine smell of tobacco that filled his office and could be revisited later by sniffing my swan.

When she was not with Ava my mother was always out. The housekeepers in the Back Flat were more and more responsible for my welfare and the house the other side of the door became quieter and quieter.

My mother was not at home most nights, but where does she go? There are whispers and murmurs that have now become familiar to me, like a soft insistent mantra. ‘There’s a new crowd arrived at the Prince’ is one. Another is ‘Peter Cooper is in town’, which always gives me a thrill in the pit of my stomach.

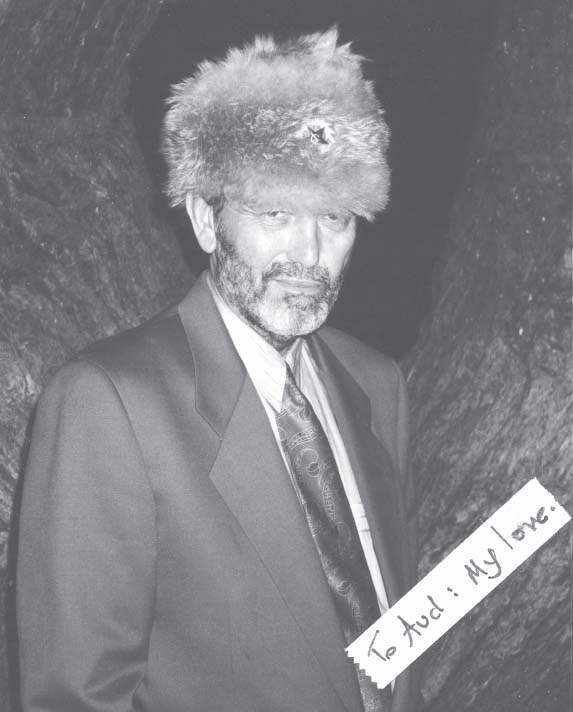

Peter Cooper sweeps into our hallway like a tornado, his black eyes shining from under a big Russian hat.

He shouts, ‘My little Aud,’ and sweeps my mother up in his arms and whirls her round and round.

I shout, ‘My turn!’ and he does the same for me, spinning me till I’m dizzy.

‘You look like a Russian Cossack in that hat, a wicked marauding Cossack,’ she tells him, and he does a Russian dance right there in our hallway, his arms folded and his legs flying out.

Peter Cooper in a Russian hat.

‘Then bring your Cossack his vodka and caviar,’ he roars.

She gets him a drink and tells him that she’s missed him, and that she can feel herself coming back to life. Then she says ‘OK! It’s Showtime!’ Which is something she says when fun things are about to happen.

I know that she will now be busy arranging parties and dates for him and his friends and, if I’m lucky, I’ll go with her and be able to watch all the excitement.

Peter Cooper is the King of Southport. He grew up, like my mother, around the Liverpool dockyards, and had invented a way of welding ships underwater and made an instant fortune. He now lives on a Californian beach with his millions and a beautiful wife, but can never bear to be away from his mates or his home town for long. It is always one big party from the day he arrives in town until the day he leaves and my mum’s job is to make that party happen. To me he fills the sky. Huge, restless, raven haired, with his booming voice and wicked laugh he is the pirate-buccaneer plaque on my bedroom wall come to life. Sitting on a bar stool, in a charming mood I can imagine him as James Bond twirling his cocktail stick, and now I can add ‘wild Cossack’ to my Peter Cooper fantasy list.

My father is upstairs, very sick, and I hear half-whispered conversations between him and my mum. His voice is so weak now. She sounds kind and gentle, but firm.

She is telling him she is going out. He doesn’t ask where, or who with.

‘When do you think you’ll be back?’

‘Not too late,’ she promises, but it isn’t true. She will be late.

‘I’ll see you in the morning. You sleep now’ – and she kisses him.

‘Tell Sally to come in.’

I’ve been waiting for this, listening at the door. She comes out and says that I can go in and sit with him.

‘Quietly, mind. Don’t tire him out with too much chatter.’ So I sit on the edge of the bed, and try to talk in a soft voice and tell him about things that are cheerful.

I show him the things I’ve made for him: drawings, or stories and poems I’ve written, as he likes that. After a while, his head falls back onto the pillow and he looks exhausted.

‘Shall I tuck you in?’ I love to kiss him, and do this as if he was the child. Sometimes when I leave him I want to cry, but I don’t let him see this. When I’m called away, I go through to the Back Flat for my tea, and wait for the housekeeper to tell me when to go to bed.

During the day I can sometimes go out with my mother and if Peter Cooper is in town, or there is an important crowd at the Prince, we go there. Aside from those two palaces to our kingdom, Marshall and Snelgrove department store, and ‘the Prince’, there was a third, the Kingsway Casino. But ‘the Kingsway’ was barred to children, which only made it more tantalizing as I peered in past the bouncers to the huge chandeliers and forbidden sumptuous spaces beyond. Inside I would see my mother deep in conversation with someone, doing ‘business’ as she called it, and I knew I had to wait patiently or next time I might be left at home.

‘The Prince’ was a grand hotel that seemed to me like the centre of the world. Through the great doors with their uniformed footmen was a blazing coal fire and, at Christmas, a swan carved of ice. Ava and Anthony stayed there every year when their housekeeper was on holiday, and Audrey and I would visit for lavish teas. And the rest of the year my mother was a constant visitor to the lounge and bar areas where she was often ‘talking business’.

If she had to take me with her, I would be told to go and ‘explore’.

‘Scoot and skidaddle, go away and have fun,’ she’d say, sending me off with a blown kiss, and I would run away to lose myself for hours. Through one set of double doors off the thickly carpeted corridors was a grand ballroom with a glass dome and a sweeping staircase leading up to a balcony. My mother had showed me this room and told me about her New Year’s Eve surprise:

‘They wheeled me in right here to the middle of the ballroom dance floor. I was crouching down in the trolley with a tablecloth over it, so they couldn’t see me. There was a huge iced cake on top that I could stand up in.’

She demonstrated, crouching down. ‘Then they started the countdown: ten – doing! Nine – doing! Eight – doing!’

I joined in with her. On the last chime she leapt up, showing me how on the final chime of midnight, she would burst forth in a sequined costume.

‘Happy New Year!’

‘And were all the people at the party terribly amazed?’

‘Astonished! They couldn’t see that the cake had a crêpe-paper top. And then I would throw streamers and the band would play.’

Alone in the ballroom’s splendour I would reenact this moment of breaking through the crêpe-paper ceiling, covered in glitter, my arms aloft, to loud applause, as the orchestra struck up ‘Auld Lang Syne’ and I threw streamers towards the cheering crowd.

My other playground was the ladies’ cloakroom, with dressing tables and tall mirrors with hinged flaps that you could stand in the middle of. If you wrapped the mirrored flaps around yourself, you would see hundreds of little girls just like me trapped in glass rooms. I would wave to them and longed to reach them, but they only waved back.

By early evening the Rolls-Royces and Jags would be three deep in the car park and the Prince bar would be in full swing, alive with laughter and gossip. I longed to go into that rich fug of brandy fumes, expensive scent and smoke. Mink coats, silky, gleaming and cool to the touch, were flung carelessly across the sofas under the jealous stares of women who had yet to be given one. My own mother’s mink was one of the loveliest, with a dark soft glow to the fur a high collar around her long neck and buttons studded with diamonds.

‘Just feel that,’ she would say dreamily, in a moment of rare satisfaction, shaking her head at the deliciousness of it.

There were brief moments, longed for, and longingly remembered, when the town drew the world to it, and these moments saved my mother’s life. Royal Birkdale Golf Club was nearby, and brought big international players, wealthy golfers, dukes and earls, to town for the weeks of the tournament. The Prince Hotel would host lavish dinners in the ballroom, and even the prime minister, Harold Wilson, came to watch the golf. My mother had some dealings with all this that were secret, and that I didn’t understand, but they added to the excited buzz of the place in an indefinable way.

The less glamorous side to our life was ‘the shops’ – my mother’s shops. I wasn’t sure how many there were, or what went on in them. I think they all looked the same: seedy rooms on back streets with blacked-out windows covered with a mesh grille. I would usually be told to wait in the car, but sometimes I would go in and sit on a stool while she talked to whoever worked there. There was a Formica counter where an old man sat smoking, and the walls were usually covered with the pinned-up racing pages of the newspaper. One shop had a row of horseshoes over the door, and my mother explained, ‘See, they must always be that way up, like a U, to hold all our luck inside and not let any of it out.’

But I imagined all our luck in there, and worried that someone might one day turn them upside down. The shops were never full – usually there were just one or two other men, shuffling about – and if a race was on there was a speaker that droned out the crackling commentary …

It was a strangely soporific chant, like drowsy wasps buzzing, trapped against the window on a hot day. It was supposed to be exciting, but instead it seemed to me like the most dull sound in the world, the essence of boredom.

It was only as I became a little older that I realized that the shops were in some way connected with things that had happened in my mother’s childhood. Little by little it came out, as I asked my innocent questions and gazed at those old photographs. What was so bad about the small squinting man beside her and her mother? If that was really her daddy, why did she hate him so much?

5

Bookie’s Runner

IN A CERTAIN MOOD, my mother would forget that I was a child and, spellbound by her own story, she would let slip the secrets of her early life. Forgetting her audience, she would begin to relive it and I would see it all come back, flickering in her eyes: the dirty windowpanes, light slicing through the smoke from the fire, and her father edgy, his muscles twitching like a hair trigger.

‘The girl has to go into the pubs; the other children do it, the job needs it, the money’s got to be made.’ They were both devastated by what he was suggesting Audrey now had to do.

I didn’t understand why my mother might sometimes tell people about this time of her life as if it was another amusing anecdote about her rackety past. ‘Of course, I was a bookie’s runner, as a child. While you were playing nicely in the park, I was going round the pubs taking bets and dodging the police.’

It wouldn’t be told to a lady, but to someone like Peter Cooper or one of his crowd; then she could make it sound like a rather racy thing to have done, although I knew that it had sickened her. Her father was something called a ‘turf accountant’. This was his new ‘business’, an illegal enterprise which he announced to the family on his return, and my mother, aged only nine or ten, was to work for him.

‘He could see I was perfect for the job, and if the police came into the pubs and asked what I was doing I’d to say my ma had sent me to fetch my father.’

‘Could he have gone to prison?’ I’d ask, urging her to give me as many gory details as possible.

‘Yes, the police were always after us. We’d come running back from the pubs with all the bets, and hide under this big tarpaulin he had in the back yard. We had to put them in the “clock bag”, a leather bag that had a clock set to the time, so when the bag was sealed it showed the bets had been put in before the race started. Sometimes the other bookies, the McGanns, would come after us or tip off the police, and there would be a terrific kerfuffle.’

At night the pubs were warm and steamy, the floors sticky underfoot with spilt beer and a crunch of sawdust and cigarette butts. The public bar heaved with men – all men, except for her, the one small girl, weaving her way through it all, taking the punts. Sometimes a gentlemanly arm would help her, parting the throng of leery bodies, propping each other up, so she could pass. Mouths opened near her face, a gaping pink wetness with missing teeth, rasping their demands for this bet or that. So it went on until at last she would be pushing through those swing doors and out onto the street. It would take a moment to collect herself, and then she would run.

She shuddered. ‘They would be drunk, and saying terrible, disgusting things to me, and touching me.’ She hinted at something worse.

I believed that the rest of the story had something to do with the little coat. In the top of my mother’s wardrobe, next to the box of photographs, were a few tantalizing treasures, and among them was a tiny, precious coat with a fur collar. It was wrapped in tissue paper and kept beside my mother’s first pink satin ballet shoes. I longed to know about this carefully preserved memento, but, just like her account of what took place around the pubs, she would always stop before the end. It was only ever a tale half told.

The worst part of her life in the pubs had been returning with the betting results and dealing with men who may have lost all the money they had. Their drunken self-pity would turn to anger and the bookie’s daughter was an easy target. ‘I couldn’t tell my mother what some of them did to me. It would have hurt her so much to know what went on.’

‘What went on? And what happened to Sadie doll?’

My mother had told me about the doll with the china face and eyes that opened and shut. She’d come on a boat all the way from America, and no one in the street or the whole of Bootle had seen anything like her, or the clothes that Sadie doll had, her little coat with frog buttons and fur cuffs. But when I asked where she was now, my mother would say, ‘Oh, she got broken.’

Slowly, over the years, the story would be told, of how her mother, Rebecca, had pleaded with Len not to send Audrey into the pubs again, but then she would say the wrong thing and he’d lash out, pulling out his thick leather belt.

Rebecca Miller, ‘Nana’.

Loop by loop, burnt into Audrey’s memory, that belt and the slow intention of it. The air filling with horror and Audrey escaping, hiding in the bedroom, but she could still hear that awful sound; it went on and on … and then there was silence.

It was only when I was older that I heard how the Sadie doll lay on the floor after one of these violent outbursts from her father, the doll’s pretty pink cheek smashed, and Audrey couldn’t look at it. Her mother had to hide the doll and the coat so that Audrey would stop crying.

Audrey tried to tell her father that she couldn’t do the job any more, and the abuse he had turned on her mother now rained down on her. She saw her mother change during these years, and begin to lose hope. The little doll’s coat was always kept, as a memory of their past life. There were no more dancing classes or days out now; life became a grim round of humiliation and fear.

Then war broke out and saved her. In 1939, Liverpool’s dockyards were a prime target for the German bombers and soon they came. Rebecca and Sadie felt that evacuation could only be better for Audrey than the life she would be leaving behind, and so, aged thirteen, she joined the thousands of Merseyside children taken to Lime Street station to escape the bombing.

‘What was it like, being sent away?’ I peered at the gloomy house and imagined the small girl in the pictures being sent off on a train, a label pinned to her coat, leaving her mother to live with complete strangers.

‘As the train crowded with children pulled out of Lime Street station, some of the little ones were screaming for their mothers. I saw one mother being sick on the platform, but mine managed to stand tall as she waved me off. I was already missing her, and terrified that we didn’t know where we were going. I’d never been away from her before. Then, once we were out of Liverpool, I started to recognize the names of the stations – Freshfield, Formby … – and I knew that we must be headed for Southport I felt much better then.

‘When we arrived we all walked in a long crocodile to the Southport Evacuee Centre. There was a hall where a lady made all of us children line up till a nurse came and tugged a comb through our hair. It was full of disinfectant, which smelt horrible. We waited for ages, until someone came and took me over to meet this smartly dressed man. He was introduced to us as Mr Grimshaw, and he took me and two other girls and drove us away in a big comfortable car, all sitting on the leather back seat. Mr Grimshaw asked us all sorts of questions about our families and homes. The other two girls didn’t say much, so I did my best, answering politely, and thought that I’d made a good impression. Soon we turned into a wide leafy street with large houses surrounded by gardens.’

There was a house we sometimes drove past, and which my mother would point out to me. ‘There it is, that big house there behind the hedges.’

I’d peer at the plain red-brick villa and try to imagine arriving there to live with strangers.

‘Did it seem enormous?’ I’d ask.