Полная версия:

Diamonds at the Lost and Found

She bends and whispers, ‘Go on, just sing “Wiggly Woo” like we do at home.’

I’m given a little shove, out in front of a sea of elderly day-trippers seated in deckchairs. A man holds the microphone for me to sing and off I go.

‘There’s a worm at the bottom of the garden, and his name is Wiggly Woo.’

I glance to the side of the stage, where Mummy is mouthing the words at me, and wiggling her hips and arms, to remind me to wiggle like a worm as I sing the chorus. But without her at my side I feel lost and alone; I falter and can’t do my wiggle. As I curtsey, weak applause rises from the ranks of drowsy deckchairs.

With an air of finality my mother decided that I just could not sing, and that I had my father’s ‘two left feet’ and would never dance. My role in the double act we were fated to be was yet to emerge. For the moment I was given up on until I could display a talent for something.

For now, we both knew who was the real star. There was a big gold chocolate box with a sagging bow of ribbon glued to the top; it lived in wardrobes and I would beg for it to be lifted down and opened. Digging among the layers of photographs in different hues, I would pull them out longingly. These were small sepia windows to another life, and showed a little imp with dancing shoes and dressing up clothes grinning out at me.

WHO WAS SHE, this little girl? She was my mother, but in quite another incarnation, and living in this strange, dingy and unrecognizable world of the ‘olden days’. If I caught her in the right mood, she could be drawn back there to the Liverpool dockyards, some twenty miles away from us in Southport. It was now only a few stops on the train, or a drive down past the sand dunes and through dull suburbs, past Auntie Grace’s house, and past the war memorial and not so far at all; but it was also another place entirely: the past. Although it lay a little beyond my childish understanding, I would still feel the dark clouds of the Depression hanging heavily over Bootle’s terraced slums, and the notorious Scotland Road roaring and rattling with life through those hard times. It was a place that was dirty, noisy and vivid. When the working day at the dockyards finished, the stream of men would head straight to the pubs, and by mid evening their doorways let out blasts of smoky air and maudlin drunken singing, until closing time when fights began on the pavements and the wives appeared, shouting, trying to get their husbands away home.

Nearby, at Uncle Charlie’s coalyard, my mother – then Audrey Miller, aged six or seven – would be lifted onto the kitchen table, wearing her top hat, feet in shiny new tap shoes and clutching her cane. As the family crowded around she would start to sing, tapping her toes and swishing her cane from hand to hand, practising for her role in Babes in the Wood; the pantomime was to be performed at Liverpool’s most splendid theatre, the Empire, and she was to be Bootle’s very own leading light. Here she is with her shock of red hair, an irrepressible ball of impish energy, grabbing the limelight as she flutters by with the fairy chorus. ‘Give us a turn!’ someone calls. Immediately she stops dancing and pauses wide-eyed – she knows she has the room …

‘Shhh and I’ll tell you a secret,

something to open your eyes.

Are you awfully excited?

Cos it’s going to be … a surprise!’

I learnt this same poem, widening my eyes, whispering the lines, just as she had done …

‘Daddy says there aren’t any fairies,

But Mummy whispers low.

“Don’t take any notice, darling.

There are things even daddies don’t know.”’

This little girl would see things that I would never see, although I grew up with her, hearing her stories; and as I grew older I would begin to learn her secrets, and about the darker deeds she became caught up in. Something had happened in that shadowy world, something that would affect both our futures.

MOST DAYS Mummy and I strolled down to Lord Street, the graceful boulevard around which the town of Southport arranged itself. It stretched for almost a mile, wide enough to allow for expansive gardens, which ran continuously along its length. The elegant shop façades on the other side were fronted by a long cast-iron and glass canopy with fine detailing and ornate columns wrapped with plump cherubs. There were Tea Gardens, with playing fountains, and bandstands from which music was performed. Great chestnut trees made a cool canopy overhead.

In later years, when I lived in London, I would learn not to tell people that this was one of the finest thoroughfares in the world. It would make me seem ridiculous to be claiming this for a town no one knew and usually mixed up with Stockport. If I added that Prince Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte had lived here in 1846, and it had been the inspiration for Napoleon and Haussmann’s scheme in redesigning Paris, I would be certainly mocked. But it was true, and in years to come, as I travelled the world, I would see great abandoned cities once on the Silk Route, or ruling a forgotten empire, and come to understand how easily one northern seaside town could be lost or buried under the silt of only a few decades of history.

My mother still had her postcards and pictures showing the town in the 1930s, when the rich and famous of the day came pouring out of the Garrick Theatre, the women in silks and furs, the men in evening wear and monocles. Uniformed chauffeurs waited in the glow of the street lamps, and behind them a thousand fairy lights glimmered in the trees.

Leading off from Lord Street were narrow lanes with small mysterious shops selling magical things. One grubby entrance was hidden beneath driftwood and dangling conch shells and guarded by a hanging African juju witch-doctor doll, and, even more terrifying, within, by a thin stooped old man. If you were brave enough to duck down and get past the fierce witch doctor, you came to broken steps leading to a basement cave where the old man’s shell grotto sold everything it is possible to make from seashells. These barnacled wonders were some of the earliest things I can remember wanting.

Alongside him were second-hand booksellers mixed in with greasy cafés and tawdry bucket-and-spade shops with rows of bright pink sticks of rock. These lanes led from Lord Street’s elegance to the part of town now judged to be ‘common’ and the Land of the Day-trippers. A grand Victorian promenade of large hotels, once the crown of the Riviera of the North West, was now beginning to tarnish, and beyond it the miles of pleasure gardens leading to the muddy beach were showing peeling paintwork and cracks thick with weeds.

Yet Lord Street still prospered, and incredibly an orchestra still played each day in the glass-domed restaurant of the Marshall and Snelgrove department store. This was where my mother longed to be, cocooned in its gilded calm, or at the Prince of Wales Hotel where people stepped out of Rolls-Royces to vanish through great mahogany revolving doors into a world of luxurious wealth.

This world was now lost to her. All she had was me and my daddy, her terminally ill husband, and her life in a shabby flat. So she sighed and fidgeted through most of the day, played her gramophone records over and over again, smoking her menthol cigarettes.

She would sometimes leave me with Nana and disappear for hours, till my nana stood at the window with her Parkinson’s tremor getting worse with the worry.

Sometimes mail arrived with foreign stamps, or someone telephoned from London, and my mother would brighten before falling into a deeper gloom.

My poor father, Neil, had reasons to believe that he had ruined the life of the woman he adored, and that his death would mean leaving me with a reluctant mother. Because of him, for some reason I would eventually come to understand, she hadn’t been able to marry the man she really wanted to marry, or have the glittering life she had planned; and now he was going to leave her with no money.

Did he wonder how all this would play out when he was gone, and if she would begin to chase her lost dreams once again, but with me in tow, now fated to a rackety life? Did he fear what this would mean, and how it would shape my future?

He had contracted a rare disease while serving with the RAF in Africa during the war. He now struggled to carry on working, and increasingly he came home from the office to lie down or to go to his hospital visits.

None of this was the life that my mother had hoped for, and she was never a woman to simply accept her fate. One day we were going to be far away from it all. There was nothing else for it; she was so full of wanting, and still craving all the things that she believed had slipped away from her. To get these things back she was going to have to cross a line. I don’t think she realized that this was what she was doing, or that she would be taking me with her to this life on the other side of that line; she was simply helpless and this was our fate. She had skills, honed in the back streets of Liverpool and learnt from her no-good father, which she was now quite willing to use to get her out of the mess in which she found herself, and who could blame her?

3

The Grand House

OUR TAXI PULLS UP at what seems to be a mansion. It is an enormous gloomy Victorian house of red brick smothered in a blanket of dense dusty ivy. Set back behind a busy main road, its gates open to a circular driveway and neat lawns with beds of black earth and rosebushes that point their spikes to the sky. Behind the front door is a vast tiled hallway, and then more corridors and doors. Just this hallway alone seems bigger than our entire previous flat. High ceilings look down onto rooms with new names: cloakroom, larder, dining room, salon … I have no memory of it having a kitchen at all and, if it did, I don’t believe we ever used it.

A van arrives, and a small plump man who smells of perfume begins telling the other men where to put all the big boxes.

‘Are you one of the Seven Dwarfs?’

Mummy says that was very rude and to say sorry. His name is David Glover, an antique dealer, and I watch as the stream of wooden crates begins to be unpacked; their contents are placed around the rooms and David Glover puts things on top of other things. A pillar called a torchère has a boy with wings and a bow and arrow placed on top of it; it means that you have to be very careful. In the dining room a great table of gleaming mahogany arrives, with an army of chairs to go around it that no one will ever sit on. The new furniture has names like Sheraton and Chippendale, and a sideboard called William the Third. I hide under this sideboard when Mummy’s friends come round, and I hear the sparkly glasses taken out of the cabinet and the chink of a sherry bottle. I hear her friend, Auntie Ava, ask her ‘How on earth have you afforded all this?’ and my mother touches her nose and laughs, saying, ‘That would be telling!’

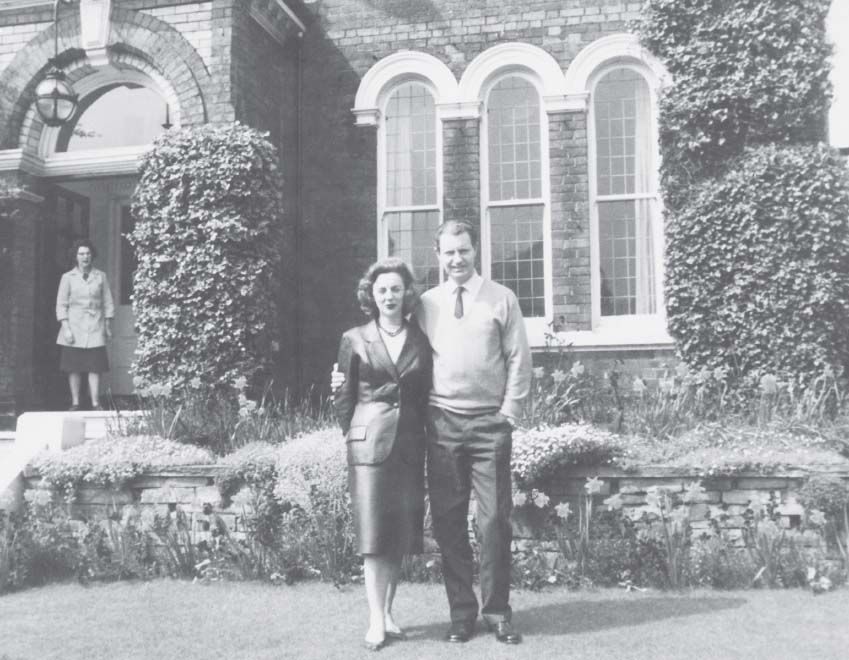

Mum and Dad, (housekeeper in background) 14 Lulworth Road, 1962.

It is a house with a mystery: I find another den at the foot of the stairs from where I overhear my Auntie Grace whisper to Uncle Phil, ‘How do you explain it, where’s she finding all this money?’

It was clearly baffling to everyone that, just as we should have been sliding into poverty, we instead moved up in the world so spectacularly. My mother had no job, and her own mother, Nana, was mainly bedridden; my daddy was now very unwell, and there was me. Yet here we all were, and she had moved us from a shabby flat on the wrong side of town into a large and impressive house with live-in staff that she had apparently paid for herself. Even at a young age I was becoming aware of these secrets that seemed to hang in the air of those endless rooms.

FROM THE HALLWAY a sweeping staircase wound up to a landing and corridor, off which there were numerous bedrooms. At night the stairwell felt even bigger, leading to a pool of darkness below. It was a house that changed shape under cover of night. Corridors stretched out forever, the stairs doubled their length and there were strange noises, whisperings and banged doors.

At the top of the staircase there was a door. This door was quite unlike all the others in the house. The others were of dark wood with brass, but this was painted white and had a plastic handle. This door led to another world, one so different it was hard to believe the two regions shared a roof. Through this door was the domain of ‘the Back Flat’. Here a succession of housekeepers lived a completely self-contained existence: in a warm, cheery fug, with a smell of sausages, and windows that streamed with condensation from the gas fire.

The Back Flat had colourful lino and carpets, and a display of decorative objects that changed with each housekeeper but somehow shared a cheeky style, and seemed of a quite different order than the objects that had been carefully positioned around the main house.

Some of these ladies came with husbands and some without. First was Alice, Irish, with pale powdery skin she liked me to kiss; then Mrs Liddel with her colostomy bag that smelt bad; then Mr and Mrs Braithwaite with their son Colin who wasn’t quite right; and there were others long since forgotten. They all lived similar domestic lives, in the glare of bright overhead fluorescent lighting, with TVs on loudly in the kitchen showing Opportunity Knocks or Coronation Street.

The housekeepers had stacks of family photographs of smiling grandchildren and mementoes from holidays, things that made me long to go on a holiday: straw donkeys in hats, a mermaid made of seashells, tea towels emblazoned with lines like ‘Glorious Devon’. From her beloved Ireland Alice brought hundreds of knick-knacks in vivid green, with winking leprechauns and shamrocks that brought you good luck.

Mrs Liddel’s ‘piggywigs’ peeped out from the window ledges, alongside decorated mugs and tea cosies; Mrs Braithwaite had her ‘plaques’, plaster sculptures which crowded the walls from their hooks – pirate ships, glades with Gypsy caravans, lagoons with Venetian gondolas and the heads of flamenco dancers. She gave me one for my room, of a pirate buccaneer with a beard who leered down at me, and I loved it passionately.

They all were happy to feed me my preferred dinner of a chip butty and a cup of sweet tea before sending me back through the door to the gloomy spaces of the landing. I hated going back across that threshold.

The Back Flat was slightly awkward and not where I belonged, but it was cosy. The Other Side, our house and my bedroom, felt dark and cold after my mother had gone out, and I was ashamed that I had to have a potty under the bed as I was too frightened to put my head outside the covers, let alone cross the landing and go down the long creaking corridor to the toilet.

As an only child adrift in this great pile of a house, I loved to hear stories of my mother’s Bootle sardine-can childhood. If on a rainy day I could coax her to bring down that box, I would rummage through the treasure trove of photographs, pulling out this one or that, pleading with her to fill in the soundtrack, to conjure the atmosphere to go with these fading images. Life at Uncle Charlie’s sounded so safe, cocooned against the poverty and violence outside.

There everyone was bundled in together around the warm fire, with the sound and smell of the horses steaming and stamping in the yard outside. Charlie Clarke’s own large family ruled the roost. ‘Nana and I just mucked in, sleeping together in a small bed and sharing a room with the cousins.’

‘Was it really, really cosy?’ I’d ask hopefully.

‘Yes I suppose it was, but very cramped and noisy. From dawn to dusk you could hear wagons clattering about in the coalyard and horses clopping in and out, and people shouting and joshing. There was always a great pot of Scouse on the stove, and it seemed to go with the endless chatter around the table: the craic.’

My mother soaked it up, as I would soak up her tales in turn: the gossip, banter and stories of her Irish family roots, friends and neighbours, in which everyone was either a saint or a sinner. Words and thoughts came tumbling out of her, her cousins would later tell me, as she was lifted onto that table to entertain, to relate the story of some small triumph or disaster to make everyone laugh or cry. She made the stories crackle with life; she could just get people, their voices and little tics. It was a gift and she was going to make it work for her. She was going to be somebody; her mother Rebecca knew it, and was quietly determined. Audrey had absorbed this into her being, understanding that she was special, and one day her life would be somewhere else far from those dirty streets.

This was where our history started; I never heard any of the Irish past from further back, except that I was told that my grandparents – Rebecca, my nana, and Len, my grandfather – had arrived here from Ireland just before Audrey, my mother, was born. She would describe the dockyard slums, built around courts, dirt-floored yards where there was a toilet and a tap shared by several families.

‘Nana was a real lady, and an angel,’ my mother always said, but I knew she had married a bad man, my grandfather, Len Miller. The family story was that he was a man with some plausible charm, which soon wore thin, revealing him as a charlatan and an operator. Nana quietly managed to get by, keeping house and her pride and doting on her small daughter.

Mum, Bootle, 1932.

Then Len disappeared, leaving them destitute. Without his income they were homeless and had to move in down the road with Uncle Charlie. Nana took on a coster barrow to sell fruit and vegetables. We had driven past that bleak stretch of road down by the docks, and my mother had pointed out to me where Nana had stood with her barrow all day and in all weathers.

‘But every night Nana twisted the rags round my hair with her poor sore fingers that were chapped from the cold, and in the morning, when they were unwound, my ringlets would tumble down past my shoulders. People would stop me in the street to exclaim at my hair.’

‘What did they say?’ I asked, wishing my own brown mop was long glossy red-gold ringlets.

‘They’d say, “Look at that colour, true auburn, and the shine to it. The glory of it,” they’d say.’

‘Tell me again about the parades?’ These were the kinds of questions she liked me to ask her: invitations to tell a story from those years when they were still happy and full of hope.

‘In the spring I’d be put in a dress made from lace tablecloths with a crown of flowers, and I’d ride just like a princess on top of Uncle Charlie’s coal wagon at the head of the May Day Parade.’

‘And where would you go?’ I’d ask, staring at the little black and white picture of the small Queen who stared back at me. She was my age, grinning at me, but from this other sooty and shadowy world.

‘We’d trundle down through the park, where I’d sit grandly on a special throne, with crowds all around watching me being crowned as Queen of May.’

‘Did they all cheer?’

‘I expect they did. Then in the summer it was the Orange Day Parade and I would be the Good King Billy, wearing a big floppy hat with an enormous feather. Uncle Charlie’s horse carried me all round the streets of Bootle.’

I loved this bit, and would ask: ‘And what was it that they shouted at you?’

‘The Protestants all cheered us, but the Catholics yelled at us, like they did in the playground, “Proddy dogs!” And me and my friends shouted back, “Cat licks!”’

I’d peer at the photos of Mummy in her finery and imagine being there, and yelling ‘Cat licks!’ too.

Her happiest moments of all were on stage, in her fairy wings and ballet dress made by Auntie Sadie, her godmother and her mother’s younger best friend. The two women were very different. Rebecca, my nana, was quiet and modest, whereas Sadie had the same high spirits as Audrey.

‘People would think I was Sadie’s little girl, as the two of us would be laughing and skipping along the road while my mother walked quietly behind us. “No, I’d say, she’s my fairy godmother!”’

Sadie was a waitress in a big department store. The wealthy merchant patrons were often generous with their tips, and she liked to spoil her little god-daughter. One day Sadie treated Rebecca and Audrey to an outing in the nearby resort of Southport. Despite being just a few miles from Liverpool, Audrey felt they had travelled far away from the grimy streets of Bootle. ‘I had a postcard which I pinned by my bed with its view of that magical place and on it was printed SOUTHPORT, RIVIERA OF THE NORTH WEST. Riviera! I dreamt of a life there, sitting sipping tea beneath those trees around the bandstand, an orchestra playing, then in the evening stepping out of a shiny car to disappear into one of the grand hotels.’

It was only as I got older that she told me how much their lives had changed when, one cold winter night, a cousin had burst into the kitchen at Uncle Charlie’s. Had they heard the news? ‘Len Miller’s been seen back in Liverpool, and he’s looking for Rebecca and the girl.’

‘I was thrilled at first. I’d been so small when my father left and I’d invented a whole life for him, telling the other children about his heroic deeds in some distant country. I think I started to think it was all real. So, when I first saw him standing there, I couldn’t believe that this hunched, weasly little man, smelling of drink, was really my own daddy.’

Worse still, he’d come to claim her. Her life would not be the same again, and I was already living with many of the consequences.

IT WAS HARD FOR ME to imagine a daddy who was horrible. One door from the first-floor landing of our house was often closed, and this was the room where my own father lay very ill; the days when he felt better were fewer and fewer.

When we first moved to this house we would both go down to the workshop he had set up in the cellar, and I longed for him to get well enough to do this again. The workshop had a delicious smell of wood and glue, and here he would build miraculous things such as record players and cocktail cabinets. He would lift me onto the workbench and let me ‘help’. I’d hold the frame down as he carefully glued onto it the wooden bas-relief shape of a puppy that he had carved specially for me. Leading from the carpentry workshop was a darkroom, pitch-black except for a red glow, and here we would develop the pictures he had taken. If the chemical smell was too strong I’d bury my head in his jumper, and he’d hug me so I could breathe in his lovely clean soapy smell. He worked quietly and intently, but every now and then he would peer at me through the darkness and say, ‘Where is she, where’s my little helper?’

‘Here I am!’ I could just make him out in the gloom. He’d lift the negatives up, choosing which to print – me, smiling just for him, freckled and happy. He would squint at each one and say, ‘Yes, here she is! And here she is again, even prettier! How ever will we choose?’

These images, and the cine films he made, became an alternative version of my childhood and fixed forever my memories of him. They would capture these years in such shimmering colour and light that they seemed to obliterate the reality of it altogether.

Gradually these days of making things from wood, or being absorbed in his darkroom with its clicking enlargers and splicing tables, became less frequent; his days of playing with me were also coming to an end, his energy draining from him till he became silent and solitary in his room. I would be told to let him rest. I would sit outside his door on the floor, with my book, feeling in some way that I was guarding him against danger, although I understood that really the danger was inside him. Sometimes I was allowed to go in and lie quietly on his bed. If he was asleep I would lie very still and watch him breathing, looking not ill but just tired.