Полная версия

Полная версияSea Power in its Relations to the War of 1812. Volume 2

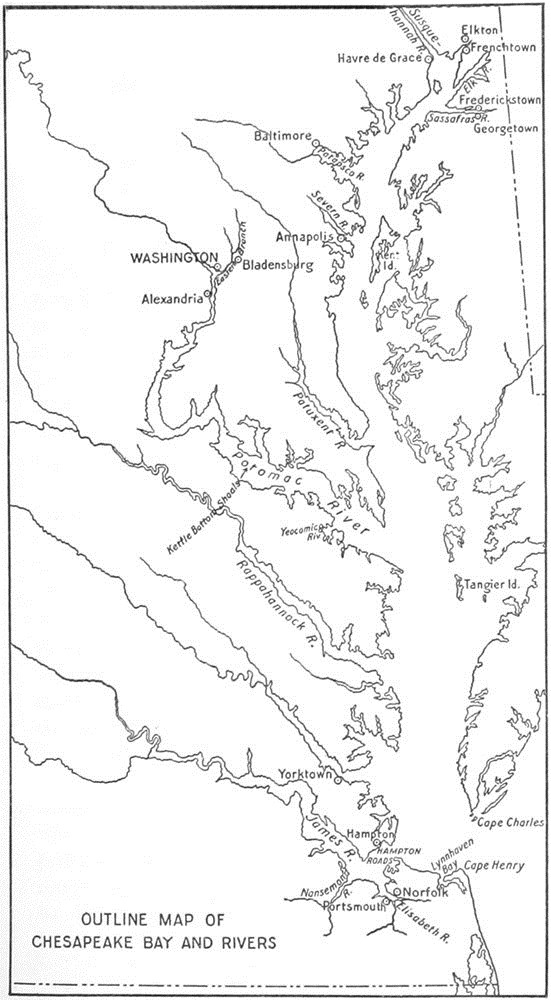

The Delaware and the Chesapeake—the latter particularly—became the principal scenes of active operations by the British navy. Here in the early part of the summer there seems to have been a formed determination on the part of Sir John Warren to satisfy his Government and people by evidence of military exertion in various quarters. Rear Admiral George Cockburn, an officer of distinction and energy, had been ordered at the end of 1812 from the Cadiz station, with four ships of the line and several smaller cruisers, to re-enforce Warren. This strong detachment, a token at once of the relaxing demand upon the British navy in Europe, and of the increasing purpose of the British Government towards the United States, joined the commander-in-chief at Bermuda, and accompanied him to the Chesapeake in March. Cockburn became second in command. Early in April the fleet began moving up the bay; an opening incident, already mentioned,152 being the successful attack by its boats upon several letters-of-marque and privateers in the Rappahannock upon the 3d of the month. Some of the schooners there captured were converted into tenders, useful for penetrating the numerous waterways which intersected the country in every direction.

The fleet, comprising several ships of the line, besides numerous smaller vessels, continued slowly upwards, taking time to land parties in many quarters, keeping the country in perpetual alarm. The multiplicity and diverseness of its operations, the particular object of which could at no moment be foreseen, made it impossible to combine resistance. The harassment was necessarily extreme, and the sustained suspense wearing; for, with reports continually arriving, now from one shore and now from the other, each neighborhood thought itself the next to be attacked. Defence depended wholly upon militia, hastily assembled, with whom local considerations are necessarily predominant. But while thus spreading consternation on either side, diverting attention from his main objective, the purpose of the British admiral was clear to his own mind. It was "to cut off the enemy's supplies, and destroy their foundries, stores, and public works, by penetrating the rivers at the head of the Chesapeake."

OUTLINE MAP OF CHESAPEAKE BAY AND RIVERS

On April 16 an advanced division arrived off the mouth of the Patapsco, a dozen miles from Baltimore. There others successively joined, until the whole force was reported on the 22d to be three seventy-fours, with several frigates and smaller vessels, making a total of fifteen. The body of the fleet remained stationary, causing the city a strong anticipation of attack; an impression conducing to retain there troops which, under a reasonable reliance upon adequate fortifications, might have been transferred to the probable scene of operations, sufficiently indicated by its intrinsic importance. Warren now constituted a light squadron of two frigates, with a half-dozen smaller vessels, including some of those recently captured. These he placed in charge of Cockburn and despatched to the head of the bay. In addition to the usual crews there went about four hundred of the naval brigade, consisting of marines and seamen in nearly equal numbers. This, with a handful of army artillerists, was the entire force. With these Cockburn went first up the Elk River, where Washington thirty years before had taken shipping on his way to the siege of Yorktown. At Frenchtown, notwithstanding a six-gun battery lately erected, a landing was effected on April 29, and a quantity of flour and army equipments were destroyed, together with five bay schooners. Many cattle were likewise seized; Cockburn, in this and other instances, offering to pay in British government bills, provided no resistance was attempted in the neighborhood. From Frenchtown he went round to the Susquehanna, to obtain more cattle from an island, just below Havre de Grace; but being there confronted on May 2 by an American flag, hoisted over a battery at the town, he proceeded to attack the following day. A nominal resistance was made; but as the British loss, here and at Frenchtown, was one wounded on each occasion, no great cause for pride was left with the defenders. Holding the inhabitants responsible for the opposition in their neighborhood, he determined to punish the town. Some houses were burned. The guns of the battery were then embarked; and during this process Cockburn himself, with a small party, marched three or four miles north of the place to a cannon foundry, where he destroyed the guns and material found, together with the buildings and machinery.

"Our small division," he reported to Warren, "has been during the whole of this day on shore, in the centre of the enemy's country, and on his high road between Baltimore and Philadelphia." The feat testified rather to the military imbecility of the United States Government during the last decade than to any signal valor or enterprise on the part of the invaders. Enough and to spare of both there doubtless was among them; for the expedition was of a kind continuously familiar to the British navy during the past twenty years, under far greater difficulty, in many parts of the world. Seeing the trifling force engaged, the mortification to Americans must be that no greater demand was made upon it for the display of its military virtues. Besides the destruction already mentioned, a division of boats went up the Susquehanna, destroyed five vessels and more flour; after which, "everything being completed to my utmost wishes, the division embarked and returned to the ships, after being twenty-two hours in constant exertion." From thence Cockburn went round to the Sassafras River, where a similar series of small injuries was inflicted, and two villages, Georgetown and Frederickstown, were destroyed, in consequence of local resistance offered, by which five British were wounded. Assurance coming from several quarters that no further armed opposition would be made, and as there was "now neither public property, vessels, nor warlike stores remaining in the neighborhood," the expedition returned down the bay, May 7, and regained the fleet.153

The history of the Delaware and its waters during this period was very much the same as that of the Chesapeake; except that, the water system of the lower bay being less extensive and practicable, and the river above narrower, there was not the scope for general marauding, nor the facility for systematic destruction, which constituted the peculiar exposure of the Chesapeake and gave Cockburn his opportunity. Neither was there the same shelter from the sweep of the ocean, nor any naval establishment to draw attention. For these reasons, the Chesapeake naturally attracted much more active operations; and Virginia, which formed so large a part of its coast-line, was the home of the President. She was also the leading member of the group of states which, in the internal contests of American politics, was generally thought to represent hatred to Great Britain and attachment to France. In both bays the American Government maintained flotillas of gunboats and small schooners, together with—in the Delaware at least—a certain number of great rowing barges, or galleys; but, although creditable energy was displayed, it is impossible to detect that, even in waters which might be thought suited to their particular qualities, these small craft exerted any substantial influence upon the movements of the enemy. Their principal effect appears to have been to excite among the inhabitants a certain amount of unreasonable expectation, followed inevitably by similar unreasoning complaint.

It is probable, however, that they to some extent restricted the movements of small foraging parties beyond the near range of their ships; and they served also the purpose of watching and reporting the dispositions of the British fleet. When it returned downwards from Cockburn's expedition, it was followed by a division of these schooners and gunboats, under Captain Charles Gordon of the navy, who remained cruising for nearly a month below the Potomac, constantly sighting the enemy, but without an opportunity offering for a blow to be struck under conditions favorable to either party. "The position taken by the enemy's ships," reported Gordon, "together with the constant protection given their small cruisers, particularly in the night, rendered any offensive operations on our part impracticable."154 In the Delaware, a British corvette, running upon a shoal with a falling tide, was attacked in this situation by a division of ten gunboats which was at hand. Such conditions were unusually favorable to them, and, though a frigate was within plain sight, she could not get within range on account of the shoalness of water; yet the two hours' action which followed did no serious injury to the grounded ship. Meantime one of the gunboats drifted from its position, and was swept by the tide out of supporting distance from its fellows. The frigate and sloop then manned boats, seven in number, pulled towards her, and despite a plucky resistance carried her; their largely superior numbers easily climbing on board her low-lying deck. Although the record of gunboats in all parts of the world is mostly unfruitful, some surprise cannot but be felt at the immunity experienced by a vessel aground under such circumstances.155

On May 13 Captain Stewart of the "Constellation" reported from Norfolk that the enemy's fleet had returned down the bay; fifteen sail being at anchor in a line stretching from Cape Henry to near Hampton Roads. Little had yet been done by the authorities to remedy the defenceless condition of the port, which he had deplored in his letter of March 17; and he apprehended a speedy attack either upon Hampton, on the north shore of the James River, important as commanding communications between Norfolk and the country above, or upon Craney Island, covering the entrance to the Elizabeth River, through the narrow channel of which the navy yard must be approached. There was a party now at work throwing up a battery on the island, on which five hundred troops were stationed, but he feared these preparations were begun too late. He had assigned seven gunboats to assist the defence. It was clear to his mind that, if Norfolk was their object, active operations would begin at one of these approaches, and not immediately about the place itself. Meanwhile, he would await developments, and postpone his departure to Boston, whither he had been ordered to command the "Constitution."

Much to Stewart's surprise, considering the force of the enemy, which he, as a seaman, could estimate accurately and compare with what he knew to be the conditions confronting them, most of the British fleet soon after put to sea with the commander-in-chief, leaving Cockburn with one seventy-four and four frigates to hold the bay. This apparent abandonment, or at best concession of further time to Craney Island, aroused in him contempt as well as wonder. He had commented a month before on their extremely circumspect management; "they act cautiously, and never separate so far from one another that they cannot in the course of a few hours give to each other support, by dropping down or running up, as the wind or tide serve."156 Such precaution, however, was not out of place when confronted with the presence of gunboats capable of utilizing calms and local conditions. To avoid exposure to useless injury is not to pass the bounds of military prudence. It was another matter to have brought so large a force, and to depart with no greater results than those of Frenchtown and Havre de Grace. "They do not appear disposed to put anything to risk, or to make an attack where they are likely to meet with opposition. Their conduct while in these waters has been highly disgraceful to their arms, and evinces the respect and dread they have for their opponents."157 He added a circumstance which throws further light upon the well-known discontent of the British crews and their deterioration in quality, under a prolonged war and the confinement attending the impressment system. "Their loss in prisoners and deserters has been very considerable; the latter are coming up to Norfolk almost daily, and their naked bodies are frequently fished up on the bay shore, where they must have been drowned in attempting to swim. They all give the same account of the dissatisfaction of their crews, and their detestation of the service they are engaged in."158 Deserters, however, usually have tales acceptable to those to whom they come.

Whether Warren was judicious in postponing attack may be doubted, but he had not lost sight of the Admiralty's hint about American frigates. There were just two in the waters of the Chesapeake; the "Constellation," 36, at Norfolk, and the "Adams," 24, Captain Charles Morris, in the Potomac. The British admiral had been notified that a division of troops would be sent to Bermuda, to be under his command for operations on shore, and he was now gone to fetch them. Early in June he returned, bringing these soldiers, two thousand six hundred and fifty in number.159 From his Gazette letters he evidently had in view the capture of Norfolk with the "Constellation"; for when he designates Hampton and Craney Island as points of attack, it is because of their relations to Norfolk.160 This justified the forecast of Stewart, who had now departed; the command of the "Constellation" devolving soon after upon Captain Gordon. In connection with the military detachment intrusted to Warren, the Admiralty, while declining to give particular directions as to its employment, wrote him: "Against a maritime country like America, the chief towns and establishments of which are situated upon navigable rivers, a force of the kind under your orders must necessarily be peculiarly formidable.... In the choice of objects of attack, it will naturally occur to you that on every account any attempt which should have the effect of crippling the enemy's naval force should have a preference."161 Except for the accidental presence of Decatur's frigates in New London, as yet scarcely known to the British commander-in-chief, Norfolk, more than any other place, met this prescription of his Government. His next movements, therefore, may be considered as resulting directly from his instructions.

The first occurrence was a somewhat prolonged engagement between a division of fifteen gunboats and the frigate "Junon," which, having been sent to destroy vessels at the mouth of the James River, was caught becalmed and alone in the upper part of Hampton Roads; no other British vessel being nearer than three miles. The cannonade continued for three quarters of an hour, when a breeze springing up brought two of her consorts to the "Junon's" aid. The gunboats, incapable of close action with a single frigate in a working breeze, necessarily now retreated. They had suffered but slightly, one killed and two wounded; but retired with the confidence, always found in the accounts of such affairs, that they had inflicted great damage upon the enemy. The commander of a United States revenue cutter, lately captured, who was on board the frigate at the time, brought back word subsequently that she had lost one man killed and two or three wounded.162 The British official reports do not allude to the affair. As regards positive results, however, it may be affirmed with considerable assurance that the military value of gunboats in their day, as a measure of coast defence, was not what they effected, but the caution imposed upon the enemy by the apprehension of what they might effect, did this or that combination of circumstances occur. That the circumstances actually almost never arose detracted little from this moral influence. The making to one's self a picture of possible consequences is a powerful factor in most military operations; and the gunboat is not without its representative to-day in the sphere of imaginative warfare.

The "Junon" business was a casual episode. Warren was already preparing for his attack on Craney Island. This little strip of ground, a half-mile long by two hundred yards across, lies within easy gunshot to the west of the Elizabeth River, a narrow channel-way, three hundred yards from edge to edge, which from Hampton Roads leads due south, through extensive flats, to Norfolk and Portsmouth. The navy yard is four miles above the island, on the west side of the river, the banks of which there have risen above the water. Up to and beyond Craney Island the river-bed proper, though fairly clear, is submerged and hidden amid the surrounding expanse of shoal water. Good pilotage, therefore, is necessary, and incidental thereto the reduction beforehand of an enemy's positions commanding the approach. Of these Craney Island was the first. From it the flats which constitute the under-water banks of the Elizabeth extend north towards Hampton Roads, for a distance of two miles, and are not traversable by vessels powerful enough to act against batteries. For nearly half a mile the depth is less than four feet, while the sand immediately round the island was bare when the tide was out.163 Attack here was possible only by boats armed with light cannon and carrying troops. On the west the island was separated from the mainland by a narrow strip of water, fordable by infantry at low tide. It was therefore determined to make a double assault,—one on the north, by fifteen boats, carrying, besides their crews, five hundred soldiers; the other on the west, by a division eight hundred strong,164 to be landed four miles away, at the mouth of the Nansemond River. The garrison of the island numbered five hundred and eighty, and one hundred and fifty seamen were landed from the "Constellation" to man one of the principal batteries.

The British plan labored under the difficulty that opposite conditions of tide were desirable for the two parties which were to act in concert. The front attack demanded high water, in order that under the impulse of the oars the boats might get as near as possible before they took the ground, whence the advance to the assault must be by wading. The flanking movement required low water, to facilitate passing the ford. Between the two, the hour was fixed for an ebbing tide, probably to allow for delays, and to assure the arrival of the infantry so as to profit by the least depth. At 11 A.M. of June 22 the boat division arrived off the northwest point of the island, opposite the battery manned by the seamen, in that day notoriously among the best of artillerists. A difference of opinion as to the propriety of advancing at all here showed itself among the senior naval officers; for there will always be among seamen a dislike to operating over unknown ground with a falling tide. The captain in command, however, overruled hesitations; doubtless feeling that in a combined movement the particular interest of one division must yield to the requirements of mutual support. A spirited forward dash was therefore made; but the guiding boat, sixty yards ahead of the others, grounded a hundred yards from the battery. One or two others, disregarding her signal, shared her mishap; and two were sunk by the American fire. Under these circumstances a seaman, sounding with a boat hook, declared that he found along side three or four feet of slimy mud. This was considered decisive, and the attack was abandoned.

The shore division had already retreated, having encountered obstacles, the precise character of which is not stated. Warren's report simply said, "In consequence of the representation of the officer commanding the troops, of the difficulty of their passing over from the land, I considered that the persevering in the attempt would cost more men than the number with us would permit, as the other forts must have been stormed before the frigate and dockyard could be destroyed." The enterprise was therefore abandoned at the threshold, because of probable ulterior difficulties, the degree of which it would require to-day unprofitable labor even to conjecture; but reduced as the affair in its upshot was to an abortive demonstration, followed by no serious effort, it probably was not reckoned at home to have fulfilled the Admiralty's injunctions, that the character as well as the interest of the country required certain results. The loss was trifling,—three killed, sixteen wounded, sixty-two missing.165

Having relinquished his purpose against Craney Island, and with it, apparently, all serious thought of the navy yard and the "Constellation", Warren next turned his attention to Hampton. On the early morning of June 26 two thousand troops were landed to take possession of the place, which they did with slight resistance. Three stand of colors were captured and seven field guns, with their equipment and ammunition. The defences of the town were destroyed; but as no further use was made of the advantage gained, the affair amounted to nothing more than an illustration on a larger scale of the guerilla depredation carried on on all sides of the Chesapeake. With it ended Warren's attempts against Norfolk. His force may have been really inadequate to more; certainly it was far smaller than was despatched to the same quarter the following year; but the Admiralty probably was satisfied by this time that he had not the enterprise necessary for his position, and a successor was appointed during the following winter.

For two months longer the British fleet as a whole remained in the bay, engaged in desultory operations, which had at least the effect of greatly increasing their local knowledge, and in so far facilitating the more serious undertakings of the next season. The Chesapeake was not so much blockaded as occupied. On June 29 Captain Cassin of the navy yard reported that six sail of the line, with four frigates, were at the mouth of the Elizabeth, and that the day before a squadron of thirteen—frigates, brigs, and schooners—had gone ten miles up the James, causing the inhabitants of Smithfield and the surroundings to fly from their homes, terrified by the transactions at Hampton. The lighter vessels continued some distance farther towards Richmond. A renewal of the attack was naturally expected; but on July 11 the fleet quitted Hampton Roads, and again ascended the Chesapeake, leaving a division of ten sail in Lynnhaven Bay, under Cape Henry. Two days later the main body entered the Potomac, in which, as has before been mentioned, was the frigate "Adams"; but she lay above the Narrows, out of reach of such efforts as Warren was willing to risk. He went as high as Blakiston Island, twenty-five to thirty miles from the river's mouth, and from there Cockburn, with a couple of frigates and two smaller vessels, tried to get beyond the Kettle Bottom Shoals, an intricate bit of navigation ten miles higher up, but still below the Narrows.166 Two of his detachment, however, took the ground; and the enterprise of approaching Washington by this route was for that time abandoned. A year afterwards it was accomplished by Captain Gordon, of the British Navy, who carried two frigates and a division of bomb vessels as far as Alexandria.

Two United States gunboats, "The Scorpion" and "Asp", lying in Yeocomico River, a shallow tributary of the Potomac ten miles from the Chesapeake, were surprised there July 14 by the entrance of the enemy. Getting under way hastily, the "Scorpion" succeeded in reaching the main stream and retreating up it; but the "Asp", being a bad sailer, and the wind contrary, had to go back. She was pursued by boats; and although an attack by three was beaten off, she was subsequently carried when they were re-enforced to five. Her commander, Midshipman Sigourney, was killed, and of the twenty-one in her crew nine were either killed or wounded. The assailants were considerably superior in numbers, as they need to be in such undertakings. They lost eight. This was the second United States vessel thus captured in the Chesapeake this year; the revenue cutter "Surveyor" having been taken in York River, by the boats of the frigate "Narcissus", on the night of June 12. In the latter instance, the sword of the commander, who survived, was returned to him the next day by the captor, with a letter testifying "an admiration on the part of your opponents, such as I have seldom witnessed, for your gallant and desperate attempt to defend your vessel against more than double your numbers."167 Trivial in themselves as these affairs were, it is satisfactory to notice that in both the honor of the flag was upheld with a spirit which is worth even more than victory. Sigourney had before received the commendation of Captain Morris, no mean judge of an officer's merits.