Полная версия

Полная версияSea Power in its Relations to the War of 1812. Volume 2

"I doubt not," wrote Captain Broke, when challenging Lawrence to a ship duel, "that you will feel convinced that it is only by repeated triumphs in even combat that your little navy can now hope to console your country for the loss of that trade it cannot protect."128 The taunt, doubtless intended to further the object of the letter by the provocation involved, was applicable as well to coasting as to deep-sea commerce. It ignored, however, the consideration, necessarily predominant with American officers, that the conditions of the war imposed commerce destruction as the principal mission of their navy. They were not indeed to shun combat, when it offered as an incident, but neither were they to seek it as a mere means of glory, irrespective of advantage to be gained. Lawrence, whom Broke's letter did not reach, was perhaps not sufficiently attentive to this motive.

The British blockade, military and commercial, the coastwise operations of their navy, and the careers of American cruisers directed to the destruction of British commerce, are then the three heads under which the ocean activities of 1813 divide. Although this chapter is devoted to the first two of these subjects, brief mention should be made here of the distant cruises of two American vessels, because, while detached from any connection with other events, they are closely linked, in time and place, with the disastrous seaboard engagement between the "Chesapeake" and "Shannon," with which the account of sea-coast maritime operations opens. On April 30 Captain John Rodgers put to sea from Boston in the frigate "President," accompanied by the frigate "Congress," Captain John Smith. Head winds immediately after sailing detained them inside of Cape Cod until May 3, and it was not till near George's Bank that any of the blockading squadron was seen. As, by the Admiralty's instructions, one of the blockaders was usually a ship of the line, the American vessels very properly evaded them. The two continued together until May 8, when they separated, some six hundred miles east of Delaware Bay. Rodgers kept along northward to the Banks of Newfoundland, hoping, at that junction of commercial highways, to fall in with a West India convoy, or vessels bound into Halifax or the St. Lawrence. Nothing, however, was seen, and he thence steered to the Azores with equal bad fortune. Obtaining thereabouts information of a homeward-bound convoy from the West Indies, he went in pursuit to the northeast, but failed to find it. Not till June 9 did he make three captures, in quick succession. Being then two thirds of the way to the English Channel, he determined to try the North Sea, shaping his course to intercept vessels bound either by the north or south of Ireland. Not a sail was met until the Shetland Islands were reached, and there were found only Danes, which, though Denmark was in hostility with Great Britain, were trading under British licenses. The "President" remained in the North Sea until the end of July, but made only two prizes, although she lay in wait for convoys of whose sailing accounts were received. Having renewed her supply of water at Bergen, in Norway, she returned to the Atlantic, made three captures off the north coast of Ireland, and thence beat back to the Banks, where two stray homeward-bound West Indiamen were at last caught. From there the ship made her way, still with a constant head wind, to Nantucket, off which was captured a British man-of-war schooner, tender to the admiral. On September 27 she anchored in Narragansett Bay, having been absent almost five months, and made twelve prizes, few of which were valuable. One, however, was a mail packet to Halifax, the capture of which, as of its predecessors, was noted by Prevost.129

The "Congress" was still less successful in material result. She followed a course which had hitherto been a favorite with American captains, and which Rodgers had suggested as alternative to his own; southeast, passing near the Cape Verde Islands, to the equator between longitudes 24° and 31° west; thence to the coast of Brazil, and so home, by a route which carried her well clear of the West India Islands. She entered Portsmouth, New Hampshire, December 14, having spent seven months making this wide sweep; in the course of which three prizes only were taken.130 It will be remembered that the "Chesapeake," which had returned only a month before the "Congress" sailed, had taken much the same direction with similar slight result.

These cruises were primarily commerce-destroying, and were pursued in that spirit, although with the full purpose of fighting should occasion arise. The paucity of result is doubtless to be attributed to the prey being sought chiefly on the high seas, too far away from the points of arrival and departure. The convoy system, rigidly enforced, as captured British correspondence shows, cleared the seas of British vessels, except in the spots where they were found congested, concentrated, by the operation of the system itself. It may be noted that the experience of all these vessels showed that nowhere was the system so rigidly operative as in the West Indies and Western Atlantic. Doubtless, too, the naval officers in command took pains to guide the droves of vessels entrusted to them over unusual courses, with a view to elude pursuers. As the home port was neared, the common disposition to relax tension of effort as the moment of relief draws nigh, co-operated with the gradual drawing together of convoys from all parts of the world to make the approaches to the English Channel the most probable scene of success for the pursuer. There the greatest number were to be found, and there presumption of safety tended to decrease carefulness. This was to be amply proved by subsequent experience. It had been predicted by Rodgers himself, although he apparently did not think wise to hazard in such close quarters so fine and large a frigate as the "President." "It is very generally believed," he had written, "that the coasts of England, Ireland, and Scotland are always swarming with British men of war, and that their commerce would be found amply protected. This, however, I well know by experience, in my voyages when a youth, to be incorrect; and that it has always been their policy to keep their enemies as far distant from their shores as possible, by stationing their ships at the commencement of a war on the enemy's coasts, and in such other distant situations, … and thereby be enabled to protect their own commerce in a twofold degree. This, however, they have been enabled to do, owing as well to the inactivity of the enemy, as to the local advantages derived from their relative situations."131

The same tendency was observable at other points of arrival, and recognition of this dictated the instructions issued to Captain Lawrence for the cruise of the "Chesapeake," frustrated through her capture by the "Shannon." Lawrence was appointed to the ship on May 6; the sailing orders issued to Captain Evans being transferred to him on that date. He was to go to the mouth of the Gulf of St. Lawrence, seeking there to intercept the military store-ships, and transports with troops, destined to Quebec and Upper Canada. "The enemy," wrote the Secretary, "will not in all probability anticipate our taking this ground with our public ships of war; and as his convoys generally separate between Cape Race and Halifax, leaving the trade of the St. Lawrence to proceed without convoy, the chance of captures upon an extensive scale is very flattering." He added the just remark, that "it is impossible to conceive a naval service of a higher order in a national point of view than the destruction of the enemy's vessels, with supplies for his army in Canada and his fleets on this station."132

Lawrence took command of the "Chesapeake" at Boston on May 20. The ship had returned from her last cruise April 9, and had been so far prepared for sea by her former commander that, as has been seen, her sailing orders were issued May 6. It would appear from the statement of the British naval historian James,133 based upon a paper captured in the ship, that the enlistments of her crew expired in April. Although there were many reshipments, and a nucleus of naval seamen, there was a large infusion of new and untrained men, amounting to a reconstitution of the ship's company. More important still was the fact that both the captain and first lieutenant were just appointed; her former first lying fatally ill at the time she sailed. The third and fourth lieutenants were also strange to her, and in a manner to their positions; being in fact midshipmen, to whom acting appointments as lieutenants were issued at Lawrence's request, by Commodore Bainbridge of the navy yard, on May 27, five days before the action. The third took charge of his division for the first time the day of the battle, and the men were personally unknown to him. The first lieutenant himself was extremely young.

The bearing of these facts is not to excuse the defeat, but to enforce the lesson that a grave military enterprise is not to be hazarded on a side issue, or on a point of pride, without adequate preparation. The "Chesapeake" was ordered to a service of very particular importance at the moment—May, 1813—when the Canada campaign was about to open. She was to act against the communications of the enemy; and while it is upon the whole more expedient, for the morale of a service, that battle with an equal should not be declined, quite as necessarily action should not be sought when it will materially interfere with the discharge of a duty intrinsically of greater consequence. The capture of a single enemy's frigate is not to be confounded with, or inflated to, that destruction of an enemy's organized force which is the prime object of all military effort. Indeed, the very purpose to which the "Chesapeake" was designated was to cripple the organized force of the British, either the army in Canada, or the navy on the lakes. The chance of a disabling blow by unexpected action in the St. Lawrence much exceeded any gain to be anticipated, even by a victorious ship duel, which would not improbably entail return to port to refit; while officers new to their duties, and unknown to their men, detracted greatly from the chances of success, should momentary disaster or confusion occur.

The blockade of Boston Harbor at this moment was conducted by Captain Philip Vere Broke of the "Shannon", a 38-gun frigate, which he had then commanded for seven years. His was one of those cases where singular merit as an officer, and an attention to duty altogether exceptional, had not yet obtained opportunity for distinction. It would probably be safe to say that no more thoroughly efficient ship of her class had been seen in the British navy during the twenty years' war with France, then drawing towards its close; but after Trafalgar Napoleon's policy, while steadily directed towards increasing the number of his ships, had more and more tended to husbanding them against a future occasion, which in the end never came. The result was a great diminution in naval combats. Hence, the outbreak of the American war, followed by three frigate actions in rapid succession, opened out a new prospect, which was none the less stimulative because of the British reverses suffered. Captain Broke was justly confident in his own leadership and in the efficiency of a ship's company, which, whatever individual changes it may have undergone, had retained its identity of organization through so many years of his personal and energetic supervision. He now reasonably hoped to demonstrate what could be done by officers and men so carefully trained. Captain Pechell of the "Santo Domingo," the flagship on the American station, wrote: "The 'Shannon's' men were better trained, and understood gunnery better, than any men I ever saw;" nevertheless, he added, "In the action with the 'Chesapeake' the guns were all laid by Captain Broke's directions, consequently the fire was all thrown in one horizontal line, not a shot going over the 'Chesapeake.'"134

The escape of the "President" and "Congress" early in May, while the "Shannon" and her consort, the "Tenedos," were temporarily off shore in consequence of easterly weather, put Broke still more upon his mettle; and, fearing a similar mishap with the "Chesapeake," he sent Lawrence a challenge.135 It has been said, by both Americans and English, that this letter was a model of courtesy. Undoubtedly it was in all respects such as a gentleman might write; but the courtesy was that of the French duellist, nervously anxious lest he should misplace an accent in the name of the man whom he intended to force into fight, and to kill. It was provocative to the last degree, which, for the end in view, it was probably meant to be. In it Broke showed himself as adroit with his pen—the adroitness of Canning—as he was to prove himself in battle. Not to speak of other points of irritation, the underlining of the words, "even combat," involved an imputation, none the less stinging because founded in truth, upon the previous frigate actions, and upon Lawrence's own capture of the "Peacock." In guns, the "Chesapeake" and "Shannon" were practically of equal force; but in the engagement the American frigate carried fifty more men than her adversary. To an invitation couched as was Broke's Lawrence was doubly vulnerable, for only six months had elapsed since he himself had sent a challenge to the "Bonne Citoyenne." With his temperament he could scarcely have resisted the innuendo, had he received the letter; but this he did not. It passed him on the way out and was delivered to Bainbridge, by whom it was forwarded to the Navy Department.

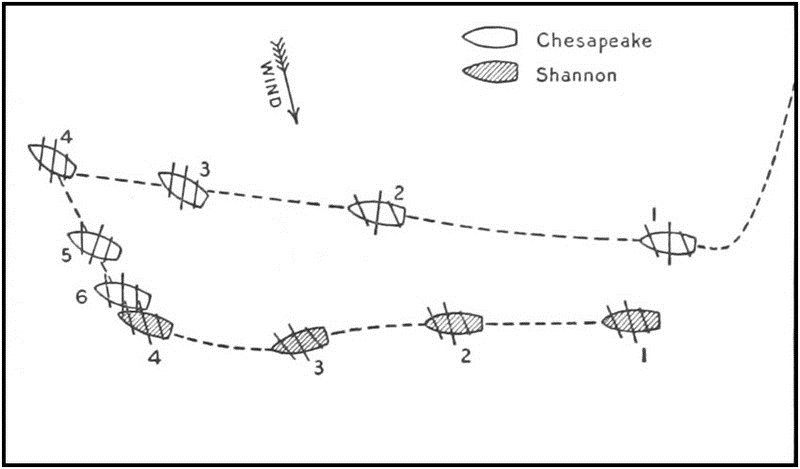

Although Broke's letter did not reach him, Captain Lawrence made no attempt to get to sea without engagement. The "Shannon's" running close to Boston Light, showing her colors, and heaving-to in defiance, served the purpose of a challenge. Cooper, who was in full touch with the naval tradition of the time, has transmitted that Lawrence went into the action with great reluctance. This could have proceeded only from consciousness of defective organization, for the heroic temper of the man was notorious, and there is no hint of that mysterious presentiment so frequent in the annals of military services. The wind being fair from the westward, the "Chesapeake," which had unmoored at 8 A.M., lifted her last anchor at noon, June 1, and made sail. The "Shannon," seeing at hand the combat she had provoked, stood out to sea until on the line between Cape Ann and Cape Cod, where she hove-to on the starboard tack, heading to the southeast. The "Chesapeake" followed under all sail until 5 P.M., when she took in her light canvas, sending the loftier—royal—yards on deck; and at 5.30 hauled up her courses, thus reducing herself to the fighting trim already assumed by her adversary. The "Shannon," which had been lying stopped for a long time, at this same moment filled her sails, to regain headway with which to manœuvre, in case her opponent's action should require it; but, after gathering speed sufficient for this purpose, the British captain again slowed his ship, by so bracing the maintopsail that it was kept shaking in the wind. Its effect being thus lost, though readily recoverable, her forward movement depended upon the sails of the fore and mizzen masts (1). In this attitude, and steering southeast by the wind, she awaited her antagonist, who was running for her weather—starboard—quarter, and whose approach, thus seconded, became now very rapid. Broke made no further change in the ship's direction, leaving the choice of windward or leeward side to Lawrence, who took the former, discarding all tactical advantages, and preferring a simple artillery duel between the vessels.

Just before she closed, the "Chesapeake" rounded-to, taking a parallel course, and backing the maintopsail (1) to reduce her speed to that of the enemy. Captain Lawrence in his eagerness had made the serious error of coming up under too great headway. At 5.50, as her bows doubled on the quarter of the "Shannon" (1), at the distance of fifty yards, the British ship opened fire, beginning with the after gun, and continuing thence forward, as each in succession bore upon the advancing American frigate. The latter replied after the second British discharge, and the combat at once became furious. The previous history of the two vessels makes it probable that the British gunnery was the better; but it is impossible, seeing the course the action finally took, so far to disentangle the effects of the fire while they were on equal terms of position, from the totals afterwards ascertained, as to say where the advantage, if any, lay during those few minutes. The testimony of the "Chesapeake's" second lieutenant, that his division—the forward one on the gun deck—fired three rounds before their guns ceased to bear, agrees with Broke's report that two or three broadsides were exchanged; and the time needed by well-drilled men to do this is well within, yet accords fairly with, James' statement, that from the first gun to the second stage in the action six minutes elapsed. During the first of this period the "Chesapeake" kept moving parallel at fifty yards distance, but gaining continually, threatening thus to pass wholly ahead, so that her guns would bear no longer. To prevent this Lawrence luffed closer to the wind to shake her sails, but in vain; the movement increased her distance, but she still ranged ahead, so that she finally reached much further than abreast of the enemy. To use the nautical expression, she was on the "Shannon's" weather bow (2). While this was happening her sailing master was killed and Lawrence wounded; these being the two officers chiefly concerned in the handling of the ship.

Diagram of the Chesapeake vs. Shannon Battle

Upon this supervened a concurrence of accidents, affecting her manageability, which initiated the second scene in the drama, and called for instantaneous action by the officers injured. The foretopsail tie being cut by the enemy's fire, the yard dropped, leaving the sail empty of wind; and at the same time were shot away the jib-sheet and the brails of the spanker. Although the latter, flying loose, tends to spread itself against the mizzen rigging, it probably added little to the effect of the after sails; but, the foresail not being set, the first two mishaps practically took all the forward canvas off the "Chesapeake." Under the combined impulses she, at 5.56, came up into the wind (3), lost her way, and, although her mainyard had been braced up, finally gathered sternboard; the upshot being that she lay paralyzed some seventy yards from the "Shannon" (3, 4, 5), obliquely to the latter's course and slightly ahead of her. The British ship going, or steering, a little off (3), her guns bore fair upon the "Chesapeake," which, by her involuntarily coming into the wind,—to such an extent that Broke thought she was attempting to haul off, and himself hauled closer to the wind in consequence (4),—lost in great measure the power of reply, except by musketry. The British shot, entering the stern and quarter of her opponent, swept diagonally along the after parts of the spar and main decks, a half-raking fire.

Under these conditions Lawrence and the first lieutenant were mortally wounded, the former falling by a musket-ball through his body; but he had already given orders to have the boarders called, seeing that the ship must drift foul of the enemy (5). The chaplain, who in the boarding behaved courageously, meeting Broke in person with a pistol-shot, and receiving a cutlass wound in return, was standing close by the captain at this instant. He afterwards testified that as Lawrence cried "Boarders away", the crews of the carronades ran forward; which corresponds to Broke's report that, seeing the enemy flinching from their guns, he then gave the order for boarding. This may have been, indeed, merely the instinctive impulse which drives disorganized men to seek escape from a fire which they cannot return; but if Cooper is correct in saying that it was the practice of that day to keep the boarders' weapons, not by their side, but on the quarter-deck or at the masts, it may also have been that this division, which had so far stuck to its guns while being raked, now, at the captain's call, ran from them to get the side-arms. At the Court of Inquiry it was in evidence that these men were unarmed; and one of them, a petty officer, stated that he had defended himself with the monkey tail of his gun. Whatever the cause, although there was fighting to prevent the "Chesapeake" from being lashed to the "Shannon", no combined resistance was offered abaft the mainmast. There the marines made a stand, but were overpowered and driven forward. The negro bugler of the ship, who should have echoed Lawrence's summons, was too frightened to sound a note, and the voices of the aids, who shouted the message to the gun deck, were imperfectly heard; but, above all, leaders were wanting. There was not on the upper deck an officer above the grade of midshipman; captain, first lieutenant, master, marine officer, and even the boatswain, had been mortally wounded before the ships touched. The second lieutenant was in charge of the first gun division, at the far end of the deck below, as yet ignorant how the fight was going, and that the fate of his superiors had put him in command. Of the remaining lieutenants, also stationed on the gun deck, the fourth had been mortally wounded by the first broadside; while the third, who had heard the shout for boarders, committed the indiscretion, ruinous to his professional reputation, of accompanying those who, at the moment the ships came together, were carrying below the wounded captain.

Before the new commanding officer could get to the spar deck, the ships were in contact. According to the report of Captain Broke, the most competent surviving eye-witness, the mizzen channels of the "Chesapeake" locked in the fore-rigging of the "Shannon." "I went forward," he continues, "to ascertain her position, and observing that the enemy were flinching from their guns, I gave orders to prepare for boarding." When the "Chesapeake's" second lieutenant reached the forecastle, the British were in possession of the after part of the ship, and of the principal hatchways by which the boarders of the after divisions could come up. He directed the foresail set, to shoot the ship clear, to prevent thus a re-enforcement to the enemy already on board; and he rallied a few men, but was himself soon wounded and thrown below. In brief, the fall of their officers and the position of the ship, in irons and being raked, had thrown the crew into the confusion attendant upon all sudden disaster. From this state only the rallying cry of a well-known voice and example can rescue men. "The enemy," reported Broke, "made a desperate but disorderly resistance." The desperation of brave men is the temper which at times may retrieve such conditions, but it must be guided and fashioned by a master spirit into something better than disorder, if it is to be effective. Disorder at any stage of a battle is incipient defeat; supervening upon the enemy's gaining a commanding position it commonly means defeat consummated.

Fifteen minutes elapsed from the discharge of the first gun of the "Shannon" to the "Chesapeake's" colors being hauled down. This was done by the enemy, her own crew having been driven forward. In that brief interval twenty-six British were killed and fifty-six wounded; of the Americans forty-eight were killed and ninety-nine wounded. In proportion to the number on board each ship when the action began, the "Shannon" lost in men 24 per cent; the "Chesapeake" 46 per cent, or practically double.

Although a certain amount of national exultation or mortification attends victory or defeat in an international contest, from a yacht race to a frigate action, there is no question of national credit in the result where initial inequality is great, as in such combats as that of the "Chesapeake" and "Shannon," or the "Constitution" and "Guerrière." It is possible for an officer to command a ship for seven years, as Broke had, and fail to make of her the admirable pattern of all that a ship of war should be, which he accomplished with the "Shannon"; but no captain can in four weeks make a thoroughly efficient crew out of a crowd of men newly assembled, and never out of harbor together. The question at issue is not national, but personal; it is the credit of Captain Lawrence. That it was inexpedient to take the "Chesapeake" into action at all at that moment does not admit of dispute; though much allowance must be made for a gallant spirit, still in the early prime of life, and chafing under the thought that, should he get to sea by successful evasion, he would be open to the taunt, freely used by Broke,136 of dodging, "eluding," an enemy only his equal in material force.