Полная версия

Полная версияIsland Life; Or, The Phenomena and Causes of Insular Faunas and Floras

The light tint indicates a depth of less than 100 fathoms.

The figures show the depth in fathoms.

The narrow channel between Norway and Denmark is 2,580 feet deep.

Beyond this line the sea deepens rapidly to the 500 and 1,000 fathom lines, the distance between 100 and 1,000 fathoms being from twenty to fifty miles, except where there is a great outward curve to include the Porcupine Bank 170 miles west of Galway, and to the north-west of Caithness where a narrow ridge less than 500 fathoms below the surface joins the extensive bank under 300 fathoms, on which are situated the Faroe Islands and Iceland, and which stretches across to Greenland. In the North Channel between Ireland and Scotland, and in the Minch between the outer Hebrides and Skye, are a series of hollows in the sea-bottom from 100 to 150 fathoms deep. These correspond exactly to the points between the opposing highlands where the greatest accumulations of ice would necessarily occur during the glacial epoch, and they may well be termed submarine lakes, of exactly the same nature as those which occur in similar positions on land.

Proofs of Former Elevation—Submerged Forests.—What renders Britain particularly instructive as an example of a recent continental island is the amount of direct evidence that exists, of several distinct kinds, showing that the land has been sufficiently elevated (or the sea depressed) to unite it with the Continent,—and this at a very recent period. The first class of evidence is the existence, all round our coasts, of the remains of submarine forests often extending far below the present low-water mark. Such are the submerged forests near Torquay in Devonshire, and near Falmouth in Cornwall, both containing stumps of trees in their natural position rooted in the soil, with deposits of peat, branches, and nuts, and often with remains of insects and other land animals. These occur in very different conditions and situations, and some have been explained by changes in the height of the tide, or by pebble banks shutting out the tidal waters from estuaries; but there are numerous examples to which such hypotheses cannot apply, and which can only be explained by an actual subsidence of the land (or rise of the sea-level) since the trees grew.

We cannot give a better idea of these forests than by quoting the following account by Mr. Pengelly of a visit to one which had been exposed by a violent storm on the coast of Devonshire, at Blackpool near Dartmouth:—

"We were so fortunate as to reach the beach at spring-tide low-water, and to find, admirably exposed, by far the finest example of a submerged forest which I have ever seen. It occupied a rectangular area, extending from the small river or stream at the western end of the inlet, about one furlong eastward; and from the low-water line thirty yards up the strand. The lower or seaward portion of the forest area, occupying about two-thirds of its entire breadth, consisted of a brownish drab-coloured clay, which was crowded with vegetable débris, such as small twigs, leaves, and nuts. There were also numerous prostrate trunks and branches of trees, lying partly imbedded in the clay, without anything like a prevalent direction. The trunks varied from six inches to upwards of two feet in diameter. Much of the wood was found to have a reddish or bright pink hue, when fresh surfaces were exposed. Some of it, as well as many of the twigs, had almost become a sort of ligneous pulp, while other examples were firm, and gave a sharp crackling sound on being broken. Several large stumps projected above the clay in a vertical direction, and sent roots and rootlets into the soil in all directions and to considerable distances. It was obvious that the movement by which the submergence was effected had been so uniform as not to destroy the approximate horizontality of the old forest ground. One fine example was noted of a large prostrate trunk having its roots still attached, some of them sticking up above the clay, while others were buried in it. Hazelnuts were extremely abundant—some entire, others broken, and some obviously gnawed.... It has been stated that the forest area reached the spring-tide low-water line; hence as the greatest tidal range on this coast amounts to eighteen feet, we are warranted in inferring that the subsidence amounted to eighteen feet as a minimum, even if we suppose that some of the trees grew in a soil the surface of which was not above the level of high water. There is satisfactory evidence that in Torbay it was not less than forty feet, and that in Falmouth Harbour it amounted to at least sixty-seven feet."131

On the coast of the Bristol Channel similar deposits occur, as well as along much of the coast of Wales and in Holyhead Harbour. It is believed by geologists that the whole Bristol Channel was, at a comparatively recent period, an extensive plain, through which flowed the River Severn; for in addition to the evidence of submerged forests there are on the coast of Glamorganshire numerous caves and fissures in the face of high sea cliffs, in one of which no less than a thousand antlers of the reindeer were found, the remains of animals which had been devoured there by bears and hyænas; facts which can only be explained by the existence of some extent of dry land stretching seaward from the present cliffs, but since submerged and washed away. This plain may have continued down to very recent times, since the whole of the Bristol Channel to beyond Lundy Island is under twenty-five fathoms deep. In the east of England we have a similar forest-bed at Cromer in Norfolk; and in the north of Holland an old land surface has been found fifty-six feet below high-water mark.

Buried River Channels.—Still more remarkable are the buried river channels which have been traced on many parts of our coasts. In order to facilitate the study of the glacial deposits of Scotland, Dr. James Croll obtained the details of about 250 bores put down in all parts of the mining districts of Scotland for the purpose of discovering minerals.132 These revealed the interesting fact that there are ancient valleys and river channels at depths of from 100 to 260 feet below the present sea-level. These old rivers sometimes run in quite different directions from the present lines of drainage, connecting what are now distinct valleys; and they are so completely filled up and hidden by boulder clay, drift, and sands, that there is no indication of their presence on the surface, which often consists of mounds or low hills more than 100 feet high. One of these old valleys connects the Clyde near Dumbarton with the Forth at Grangemouth, and appears to have contained two streams flowing in opposite directions from a watershed about midway at Kilsith. At Grangemouth the old channel is 260 feet below the sea-level. The watershed at Kilsith is now 160 feet above the sea, the old valley bottom being 120 feet deep or forty feet above the sea. In some places the old valley was a ravine with precipitous rocky walls, which have been found in mining excavations. Sir A. Geikie, who has himself discovered many similar buried valleys, is of opinion that "they unquestionably belong to the period of the boulder clay."

We have here a clear proof that, when these rivers were formed, the land must have stood in relation to the sea at least 260 feet higher than it does now, and probably much more; and this is sufficient to join England to the continent. Supporting this evidence, we have freshwater or littoral shells found at great depths off our coasts. Mr. Godwin Austen records the dredging up of a freshwater shell (Unio pictorum) off the mouth of the English Channel between the fifty fathom and 100 fathom lines, while in the same locality gravel banks with littoral shells now lie under sixty or seventy fathoms water.133 More recently Mr. Gwyn Jeffreys has recorded the discovery of eight species of fossil arctic shells off the Shetland Isles in about ninety fathoms water, all being characteristic shallow water species, so that their association at this great depth is a distinct indication of considerable subsidence.134

Time of Last Union with the Continent.—The period when this last union with the continent took place was comparatively recent, as shown by the identity of the shells with living species, and the fact that the buried river channels are all covered with clays and gravels of the glacial period, of such a character as to indicate that most of them were deposited above the sea-level. From these and various other indications geologists are all agreed that the last continental period, as it is called, was subsequent to the greatest development of the ice, but probably before the cold epoch had wholly passed away. But if so recent, we should naturally expect our land still to show an almost perfect community with the adjacent parts of the continent in its natural productions; and such is found to be the case. All the higher and more perfectly organised animals are, with but few exceptions, identical with those of France and Germany; while the few species still considered to be peculiar may be accounted for either by an original local distribution, by preservation here owing to favourable insular conditions, or by slight modifications having been caused by these conditions resulting in a local race, sub-species, or species.

Why Britain is Poor in Species.—The former union of our islands with the continent, is not, however, the only recent change they have undergone. There have been partial submergences to the depth of from one hundred to perhaps three hundred feet over a large part of our country; while during the period of maximum glaciation the whole area north of the Thames was buried in snow and ice. Even the south of England must have suffered the rigour of an almost arctic climate, since Mr. Clement Reid has shown that floating ice brought granite blocks from the Channel Islands to the coast of Sussex. Such conditions must have almost exterminated our preexisting fauna and flora, and it was only during the subsequent union of Britain with the continent that the bulk of existing animals and plants could have entered our islands. We know that just before and during the glacial period we possessed a fauna almost or quite identical with that of adjacent parts of the continent and equally rich in species. The glaciation and submergence destroyed much of this fauna; and the permanent change of climate on the passing away of the glacial conditions appears to have led to the extinction or migration of many species in the adjacent continental areas, where they were succeeded by the assemblage of animals now occupying Central Europe. When England became continental, these entered our country; but sufficient time does not seem to have elapsed for the migration to have been completed before subsidence again occurred, cutting off the further influx of purely terrestrial animals, and leaving us without the number of species which our favourable climate and varied surface entitle us to.

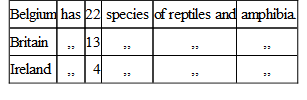

To this cause we must impute our comparative poverty in mammalia and reptiles—more marked in the latter than the former, owing to their lower vital activity and smaller powers of dispersal. Germany, for example, possesses nearly ninety species of land mammalia, and even Scandinavia about sixty, while Britain has only forty, and Ireland only twenty-two. The depth of the Irish Sea being somewhat greater than that of the German Ocean, the connecting land would there probably be of small extent and of less duration, thus offering an additional barrier to migration, whence has arisen the comparative zoological poverty of Ireland. This poverty attains its maximum in the reptiles, as shown by the following figures:—

Where the power of flight existed, and thus the period of migration was prolonged, the difference is less marked; so that Ireland has seven bats to twelve in Britain, and about 110 as against 130 land-birds.

Plants, which have considerable facilities for passing over the sea, are somewhat intermediate in proportionate numbers, there being about 970 flowering plants and ferns in Ireland to 1,425 in Great Britain,—or almost exactly two-thirds, a proportion intermediate between that presented by the birds and the mammalia.

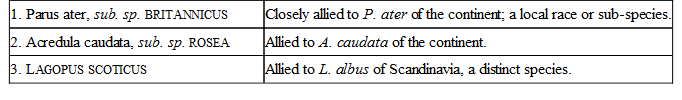

Peculiar British Birds.—Among our native mammalia, reptiles, and amphibia, it is the opinion of the best authorities that we possess neither a distinct species nor distinguishable variety. In birds, however, the case is different, since some of our species, in particular our coal-tit and long-tailed tit, present well-marked differences of colour as compared with continental specimens; and in Mr. Dresser's work on the Birds of Europe they are considered to be distinct species, while Professor Newton, in his new edition of Yarrell's British Birds, does not consider the difference to be sufficiently great or sufficiently constant to warrant this, and therefore classes them as insular races of the continental species. We have, however, one undoubted case of a bird peculiar to the British Isles, in the red grouse (Lagopus scoticus), which abounds in Scotland, Ireland, the north of England, and Wales, and is very distinct from any continental species, although closely allied to the willow grouse of Scandinavia. This latter species resembles it considerably in its summer plumage, but becomes pure white in winter; whereas our species retains its dark plumage throughout the year, becoming even darker in winter than in summer. We have here therefore a most interesting example of an insular form in our own country; but it is difficult to determine how it originated. On the one hand, it may be an old continental species which during the glacial epoch found a refuge here when driven from its native haunts by the advancing ice; or, on the other hand, it may be a descendant of the Northern willow grouse, which has lost its power of turning white in winter owing to its long residence in the lowlands of an island where there is little permanent snow, and where assimilation in colour to the heather among which it lurks is at all times its best protection. In either case it is equally interesting, as the one large and handsome bird which is peculiar to our islands notwithstanding their recent separation from the continent.

The following is a list of the birds now held to be peculiar to the British Isles:—

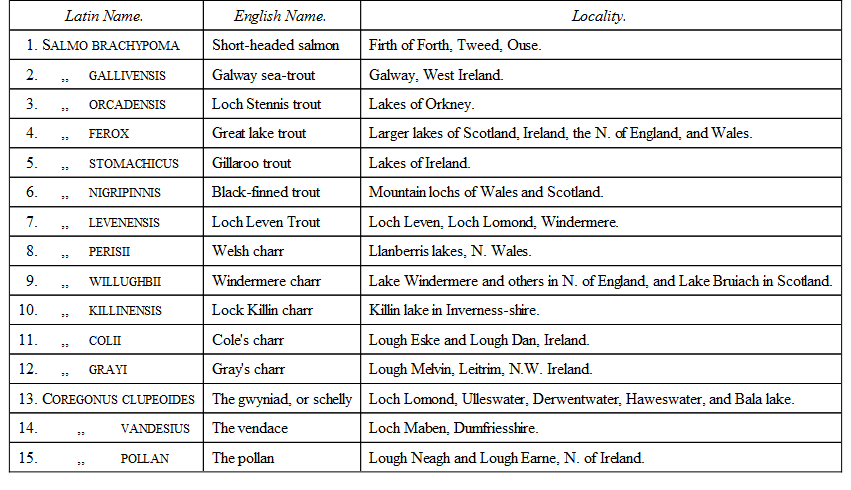

Freshwater Fishes.—Although the productions of fresh waters have generally, as Mr. Darwin has shown, a wide range, fishes appear to form an exception, many of them being extremely limited in distribution. Some are confined to particular river valleys or even to single rivers, others inhabit the lakes of a limited district only, while some are confined to single lakes, often of small area, and these latter offer examples of the most restricted distribution of any organisms whatever. Cases of this kind are found in our own islands, and deserve our especial attention. It has long been known that some of our lakes possessed peculiar species of trout and charr, but how far these were unknown on the continent, and how many of those in different parts of our islands were really distinct, had not been ascertained till Dr. Günther, so well known for his extensive knowledge of the species of fishes, obtained numerous specimens from every part of the country, and by comparison with all known continental species determined their specific differences. The striking and unexpected result has thus been attained, that no less than fifteen well-marked species of freshwater fishes are altogether peculiar to the British Islands. The following is the list, with their English names and localities:—135

Freshwater Fishes peculiar to the British Isles.

These fifteen peculiar fishes differ from each other and from all British and continental species, not in colour only, but in such important structural characters as the number and size of the scales, form and size of the fins, and the form or proportions of the head, body, or tail. Some of them, like S. killinensis and the Coregoni are in fact, as Dr. Günther assures me, just as good and distinct species as any other recognised species of fish. It may indeed be objected that, until all the small lakes of Scandinavia are explored, and their fishes compared with ours, we cannot be sure that we have any peculiar species. But this objection has very little weight if we consider how our own species vary from lake to lake and from island to island, so that the Orkney species is not found in Scotland, and only one of the peculiar British species extends to Ireland, which has no less than five species altogether peculiar to it. If the species of our own two islands are thus distinct, what reason have we for believing that they will be otherwise than distinct from those of Scandinavia? At all events, with the amount of evidence we already possess of the very restricted ranges of many of our species, we must certainly hold them to be peculiar till they have been proved to be otherwise.

The great speciality of the Irish fishes is very interesting, because it is just what we should expect on the theory of evolution. In Ireland the two main causes of specific change—isolation and altered conditions—are each more powerful than in Britain. Whatever difficulty continental fishes may have in passing over to Britain, that difficulty will certainly be increased by the second sea passage to Ireland; and the latter country has been longer isolated, for the Irish Sea with its northern and southern channels is considerably deeper than the German Ocean and the Eastern half of the English Channel, so that, when the last subsidence occurred, Ireland would have been an island for some length of time while England and Scotland still formed part of the continent. Again, whatever differences have been produced by the exceptional climate of our islands will have been greater in Ireland, where insular conditions are at a maximum, the abundance of moisture and the equability of temperature being far more pronounced than in any other part of Europe.

Among the remarkable instances of limited distribution afforded by these fishes, we have the Loch Stennis trout confined to the little group of lakes in the mainland of Orkney, occupying altogether an area of about ten miles by three; the Welsh charr confined to the Llanberris lakes, about three miles in length; Gray's charr confined to Lough Melvin, about seven miles long; while the Loch Killin charr, known only from a small mountain lake in Inverness-shire, and the vendace, from the equally small lakes at Loch Maben in Scotland, are two examples of restricted distribution which can hardly be surpassed.

Cause of Great Speciality in Fishes.—The reason why fishes alone should exhibit such remarkable local modifications in lakes and islands is sufficiently obvious. It is due to the extreme rarity of their transmission from one lake to another. Just as we found to be the case in Oceanic Islands, where the means of transmission were ample hardly any modification of species occurred, while where these means were deficient and individuals once transported remained isolated during a long succession of ages, their forms and characters became so much changed as to bring about what we term distinct species or even distinct genera,—so these lake fishes have become modified because the means by which they are enabled to migrate so rarely occur. It is quite in accordance with this view that some of the smaller lakes contain no fishes, because none have ever been conveyed to them. Others contain several; and some fishes which have peculiarities of constitution or habits which render their transmission somewhat less difficult occur in several lakes over a wide area of country, though only one appears to be common to the British and Irish lakes.

The manner in which fishes are enabled to migrate from lake to lake is unknown, but many suggestions have been made. It is a fact that whirlwinds and waterspouts sometimes carry living fish in considerable numbers and drop them on the land. Here is one mode which might certainly have acted now and then in the course of thousands of years, and the eggs of fishes may have been carried with even greater ease. Again we may well suppose that some of these fish have once inhabited the streams that enter or flow out of the lakes as well as the lakes themselves; and this opens a wide field for conjecture as to modes of migration, because we know that rivers have sometimes changed their courses to such an extent as to form a union with distinct river basins. This has been effected either by floods rising over low watersheds, by elevations of the land changing lines of drainage, or by ice blocking up valleys and compelling the streams to flow over watersheds to find an outlet. This is known to have occurred during the glacial epoch, and is especially manifest in the case of the Parallel Roads of Glenroy, and it probably affords the true solution of many of the cases in which existing species of fish inhabit distinct river basins whether in streams or lakes. If a fish thus wandered out of one river-basin into another, it might then retire up the streams to some of the lakes, where alone it might find conditions favourable to it. By a combination of the modes of migration here indicated it is not difficult to understand how so many species are now common to the lakes of Wales, Cumberland, and Scotland, while others less able to adapt themselves to different conditions have survived only in one or two lakes in a single district; or these last may have been originally identical with other forms, but have become modified by the particular conditions of the lake in which they have found themselves isolated.

Peculiar British Insects.—We now come to the class of insects, and here we have much more difficulty in determining what are the actual facts, because new species are still being yearly discovered and considerable portions of Europe are but imperfectly explored. It often happens that an insect is discovered in our islands, and for some years Britain is its only recorded locality; but at length it is found on some part of the continent, and not unfrequently has been all the time known there, but disguised by another name, or by being classed as a variety of some other species. This has occurred so often that our best entomologists have come to take it for granted that all our supposed peculiar British species are really natives of the continent and will one day be found there; and owing to this feeling little trouble has been taken to bring together the names of such as from time to time remain known from this country only. The view of the probable identity of our entire insect-fauna with that of the continent has been held by such well-known authorities as the late Mr. E. C. Rye and Dr. D. Sharp for the beetles, and by Mr. H. T. Stainton for butterflies and moths; but as we have already seen that among two orders of vertebrates—birds and fishes—there are undoubtedly peculiar British species, it seems to me that all the probabilities are in favour of there being a much larger number of peculiar species of insects. In every other island where some of the vertebrates are peculiar—as in the Azores, the Canaries, the Andaman Islands, and Ceylon—the insects show an equal if not a higher proportion of speciality, and there seems no reason whatever why the same law should not apply to us. Our climate is undoubtedly very distinct from that of any part of the continent, and in Scotland, Ireland, and Wales we possess extensive tracts of wild mountainous country where a moist uniform climate, an alpine or northern vegetation, and a considerable amount of isolation, offer all the conditions requisite for the preservation of some species which may have become extinct elsewhere, and for the slight modification of others since our last separation from the continent. I think, therefore, that it will be very interesting to take stock, as it were, of our recorded peculiarities in the insect world, for it is only by so doing that we can hope to arrive at any correct solution of the question on which there is at present so much difference of opinion. For the list of Coleoptera with the accompanying notes I was originally indebted to the late Mr. E. C. Rye; and Dr. Sharp also gave me valuable information as to the recent occurrence of some of the supposed peculiar species on the continent. The list has now been revised by the Rev. Canon Fowler, author of the best modern work on the British Coleoptera, who has kindly furnished some valuable notes.