Полная версия

Полная версияПолная версия:

Island Life; Or, The Phenomena and Causes of Insular Faunas and Floras

Insects.—Owing to the researches of the Rev. T. Blackburn we have now a fair knowledge of the Coleopterous fauna of these islands. Unfortunately some of the most productive islands in plants—Kaui and Maui—were very little explored, but during a residence of six years the equally rich Oahu was well worked, and the general character of the beetle fauna must therefore be considered to be pretty accurately determined. Out of 428 species collected, many being obviously recent introductions, no less than 352 species and 99 of the genera appear to be quite peculiar to the archipelago. Sixty of these species are Carabidæ, forty-two are Staphylinidæ, forty are Nitidulidæ, twenty are Ptinidæ, twenty are Ciodidæ, thirty are Aglycyderidæ, forty-five are Curculionidæ, and fourteen are Cerambycidæ, the remainder being distributed among twenty-two other families. Many important families, such as Cicindelidæ, Scarabœidæ, Buprestidæ, and the whole of the enormous series of the Phytophaga are either entirely absent or are only represented by a few introduced species. In the eight families enumerated above most of the species belong to peculiar genera which usually contain numerous distinct species; and we may therefore consider these to represent the descendants of the most ancient immigrants into the islands.

Two important characteristics of the Coleopterous fauna are, the small size of the species, and the great scarcity of individuals. Dr. Sharp, who has described many of them,126 says they are "mostly small or very minute insects," and that "there are few—probably it would be correct to say absolutely none—that would strike an ordinary observer as being beautiful." Mr. Blackburn says that it was not an uncommon thing for him to pass a morning on the mountains and to return home with perhaps two or three specimens, having seen literally nothing else except the few species that are generally abundant. He states that he "has frequently spent an hour sweeping flower-covered herbage, or beating branches of trees over an inverted white umbrella without seeing the sign of a beetle of any kind." To those who have collected in any tropical or even temperate country on or near a continent, this poverty of insect life must seem almost incredible; and it affords us a striking proof of how erroneous are those now almost obsolete views which imputed the abundance, variety, size, and colour of insects to the warmth and sunlight and luxuriant vegetation of the tropics. The facts become quite intelligible, however, if we consider that only minute insects of certain groups could ever reach the islands by natural means, and that these, already highly specialised for certain defined modes of life, could only develop slowly into slightly modified forms of the original types. Some of the groups, however, are considered by Dr. Sharp to be very ancient generalised forms, especially the peculiar family Aglycyderidæ, which he looks upon as being "absolutely the most primitive of all the known forms of Coleoptera, it being a synthetic form linking the isolated Rhynchophagous series of families with the Clavicorn series. About thirty species are known in the Hawaiian Islands, and they exhibit much difference inter se." A few remarks on each of the more important of the families will serve to indicate their probable mode and period of introduction into the islands.

The Carabidæ consist chiefly of seven peculiar genera of Anchomenini comprising fifty-one species, and several endemic species of Bembidiinæ. They are highly peculiar and are all of small size, and may have originally reached the islands in the crevices of the drift wood from N.W. America which is still thrown on their shores, or, more rarely, by means of a similar drift from the N.-Western islands of the Pacific.127 It is interesting to note that peculiar species of the same groups of Carabidæ are found in the Azores, Canaries, and St. Helena, indicating that they possess some special facilities for transmission across wide oceans and for establishing themselves upon oceanic islands. The Staphylinidæ present many peculiar species of known genera. Being still more minute and usually more ubiquitous than the Carabidæ, there is no difficulty in accounting for their presence in the islands by the same means of dispersal. The Nitidulidæ, Ptinidæ, and Ciodidæ being very small and of varied habits, either the perfect insects, their eggs or larvæ, may have been introduced either by water or wind carriage, or through the agency of birds. The Curculionidæ, being wood bark or nut borers, would have considerable facilities for transmission by floating timber, fruits, or nuts; and the eggs or larvæ of the peculiar Cerambycidæ must have been introduced by the same means. The absence of so many important and cosmopolitan groups whose size or constitution render them incapable of being thus transmitted over the sea, as well as of many which seem equally well adapted as those which are found in the islands, indicate how rare have been the conditions for successful immigration; and this is still further emphasized by the extreme specialisation of the fauna, indicating that there has been no repeated immigration of the same species which would tend, as in the case of Bermuda, to preserve the originally introduced forms unchanged by the effects of repeated intercrossing.

Vegetation of the Sandwich Islands.—The flora of these islands is in many respects so peculiar and remarkable, and so well supplements the information derived from its interesting but scanty fauna, that a brief account of its more striking features will not be out of place; and we fortunately have a pretty full knowledge of it, owing to the researches of the German botanist Dr. W. Hildebrand.128

Considering their extreme isolation, their uniform volcanic soil, and the large proportion of the chief island which consists of barren lava-fields, the flora of the Sandwich Islands is extremely rich, consisting, so far as at present known, of 844 species of flowering plants and 155 ferns. This is considerably richer than the Azores (439 Phanerogams and 39 ferns), which though less extensive are perhaps better known, or than the Galapagos (332 Phanerogams), which are more strictly comparable, being equally volcanic, while their somewhat smaller area may perhaps be compensated by their proximity to the American continent. Even New Zealand with more than twenty times the area of the Sandwich group, whose soil and climate are much more varied and whose botany has been thoroughly explored, has not a very much larger number of flowering plants (935 species), while in ferns it is barely equal.

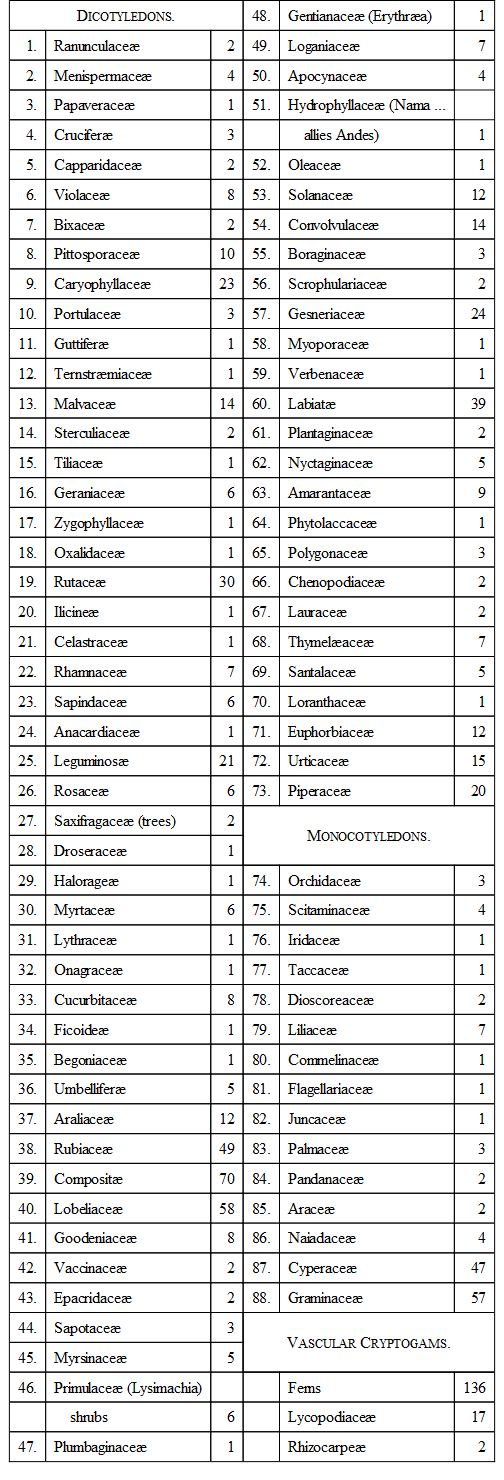

The following list gives the number of indigenous species in each natural order.

Number of Species in each Natural Order in the Hawaiian Flora, excluding the introduced Plants.

Peculiar Features of the Flora.—This rich insular flora is wonderfully peculiar, for if we deduct 115 species, which are believed to have been introduced by man, there remain 705 species of flowering plants of which 574, or more than four-fifths, are quite peculiar to the islands. There are no less than 38 peculiar genera out of a total of 265 and these 38 genera comprise 254 species, so that the most isolated forms are those which most abound and thus give a special character to the flora. Besides these peculiar types, several genera of wide range are here represented by highly peculiar species. Such are the Hawaiian species of Lobelia which are woody shrubs either creeping or six feet high, while a species of one of the peculiar genera of Lobeliaceæ is a tree reaching a height of forty feet. Shrubby geraniums grow twelve or fifteen feet high, and some vacciniums grow as epiphytes on the trunks of trees. Violets and plantains also form tall shrubby plants, and there are many strange arborescent compositæ, as in other oceanic islands.

The affinities of the flora generally are very wide. Although there are many Polynesian groups, yet Australian, New Zealand, and American forms are equally represented. Dr. Pickering notes the total absence of a large number of families found in Southern Polynesia, such as Dilleniceæa, Anonaceæ, Olacaceæ, Aurantiaceæ, Guttiferæ, Malpighiaceæ, Meliaceæ, Combretaceæ, Rhizophoraceæ, Melastomaceæ, Passifloraceæ, Cunoniaceæ, Jasminaceæ, Acanthaceæ, Myristicaceæ, and Casuaraceæ, as well as the genera Clerodendron, Ficus, and epidendric orchids. Australian affinities are shown by the genera Exocarpus, Cyathodes, Melicope, Pittosporum, and by a phyllodinous Acacia. New Zealand is represented by Ascarina, Coprosma, Acæna, and several Cyperaceæ; while America is represented by the genera Nama, Gunnera, Phyllostegia, Sisyrinchium, and by a red-flowered Rubus and a yellow-flowered Sanicula allied to Oregon species.

There is no true alpine flora on the higher summits, but several of the temperate forms extend to a great elevation. Thus Mr. Pickering records Vaccinium, Ranunculus, Silene, Gnaphalium and Geranium, as occurring above ten thousand feet elevation; while Viola, Drosera, Acæna, Lobelia, Edwardsia, Dodonæa, Lycopodium, and many Compositæ, range above six thousand feet. Vaccinium and Silene are very interesting, as they are almost peculiar to the North Temperate zone; while many plants allied to Antarctic species are found in the bogs of the high plateaux.

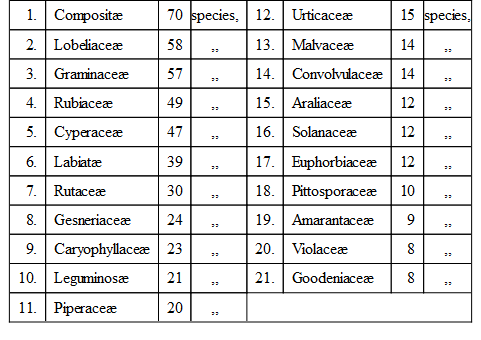

The proportionate abundance of the different families in this interesting flora is as follows:—

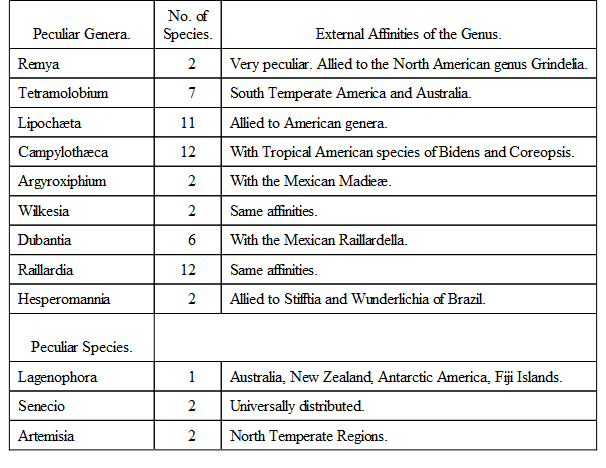

Nine other orders, Geraniaceæ, Rhamnaceæ, Rosaceæ, Myrtaceæ, Primulaceæ, Loganiaceæ, Liliaceæ, Thymelaceæ, and Cucurbitaceæ, have six or seven species each; and among the more important orders which have less than five species each are Ranunculaceæ, Cruciferæ, Vaccinacæ, Apocynaceæ, Boraginaceæ, Scrophulariaceæ, Polygonaceæ, Orchidaceæ, and Juncaceæ. The most remarkable feature here is the great abundance of Lobeliaceæ, a character of the flora which is probably unique; while the superiority of Labiatæ to Leguminosæ and the scarcity of Rosaceæ and Orchidaceæ are also very unusual. Composites, as in most temperate floras, stand at the head of the list, and it will be interesting to note the affinities which they indicate. Omitting eleven species which are cosmopolitan, and have no doubt entered with civilised man, there remain nineteen genera and seventy species of Compositæ in the islands. Sixty-one of the species are peculiar, as are eight of the genera; while the genus Lipochæta with eleven species is only known elsewhere in the Galapagos, where a single species occurs. We may therefore consider that nine out of the nineteen genera of Hawaiian Compositæ are really confined to the Archipelago. The relations of the peculiar genera and species are indicated in the following table.129

Affinities of Hawaiian Composites.

The great preponderance of American relations in the Compositæ, as above indicated, is very interesting and suggestive, since the Compositæ of Tahiti and the other Pacific Islands are allied to Malaysian types. It is here that we meet with some of the most isolated and remarkable forms, implying great antiquity; and when we consider the enormous extent and world-wide distribution of this order (comprising about ten thousand species), its distinctness from all others, the great specialisation of its flowers to attract insects, and of its seeds for dispersal by wind and other means, we can hardly doubt that its origin dates back to a very remote epoch. We may therefore look upon the Compositæ as representing the most ancient portion of the existing flora of the Sandwich Islands, carrying us back to a very remote period when the facilities for communication with America were greater than they are now. This may be indicated by the two deep submarine banks in the North Pacific, between the Sandwich Islands and San Francisco, which, from an ocean floor nearly 3,000 fathoms deep, rise up to within a few hundred fathoms of the surface, and seem to indicate the subsidence of two islands, each about as large as Hawaii. The plants of North Temperate affinity may be nearly as old, but these may have been derived from Northern Asia by way of Japan and the extensive line of shoals which run north-westward from the Sandwich Islands, as shown on our map. Those which exhibit Polynesian or Australian affinities, consisting for the most part of less highly modified species, usually of the same genera, may have had their origin at a later, though still somewhat remote period, when large islands, indicated by the extensive shoals to the south and south-west, offered facilities for the transmission of plants from the tropical portions of the Pacific Ocean.

It is in the smaller and most woody islands in the westerly portion of the group, especially in Kauai and Oahu, that the greatest number and variety of plants are found and the largest proportion of peculiar species and genera. These are believed to form the oldest portion of the group, the volcanic activity having ceased and allowed a luxuriant vegetation more completely to cover the islands, while in the larger and much newer islands of Hawaii and Maui the surface is more barren and the vegetation comparatively monotonous. Thus while twelve of the arborescent Lobeliaceæ have been found on Hawaii no less than seventeen occur on the much smaller Oahu, which has even a genus of these plants confined to it.

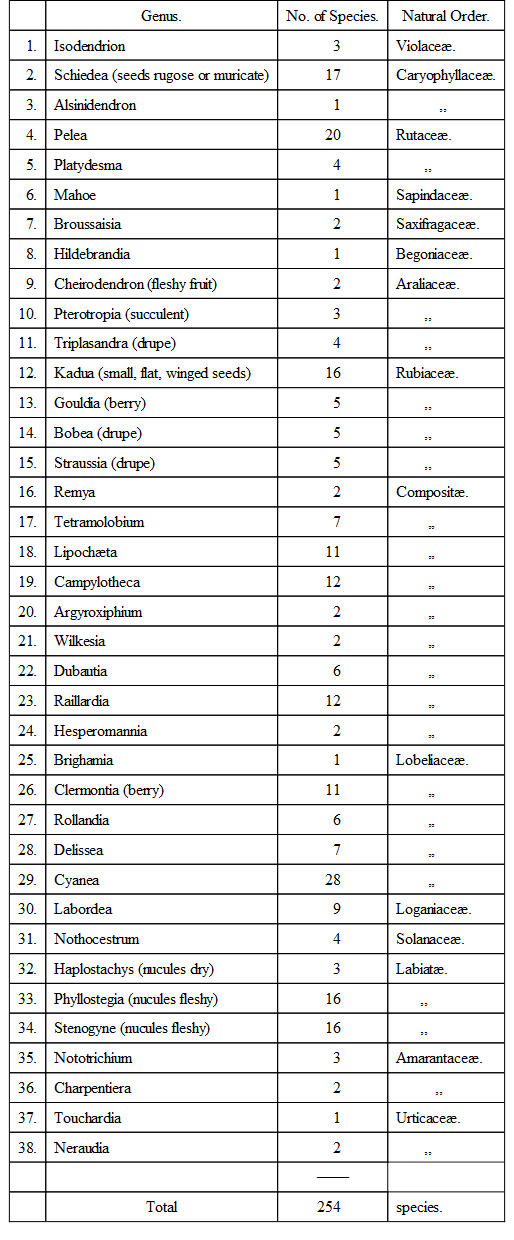

It is interesting to note that while the non-peculiar genera of flowering plants have little more than two species to a genus, the endemic genera average six and three-quarter species to a genus. These may be considered to represent the earliest immigrants which became firmly established in the comparatively unoccupied islands, and have gradually become modified into such complete harmony with their new conditions that they have developed into many diverging forms adapting them to different habitats. The following is a list of the peculiar genera with the number of species in each.

Peculiar Hawaiian Genera of Flowering Plants.

The great preponderance of the two orders Compositæ and Lobeliaceæ are what first strike us in this list. In the former case the facilities for wind-dispersal afforded by the structure of so many of the seeds render it comparatively easy to account for their having reached the islands at an early period. The Lobelias, judging from Hildebrand's descriptions, may have been transported in several different ways. Most of the endemic genera are berry-bearers and thus offer the means of dispersal by fruit-eating birds. The endemic species of the genus Lobelia have sometimes very minute seeds, which might be carried long distances by wind, while other species, especially Lobelia gaudichaudii, have a "hard, almost woody capsule which opens late," apparently well adapted for floating long distances. Afterwards "the calycine covering withers away, leaving a fenestrate woody network" enclosing the capsule, and the seeds themselves are "compressed, reniform, or orbicular, and margined," and thus of a form well adapted to be carried to great heights and distances by gales or hurricanes.

In the other orders which present several endemic genera indications of the mode of transit to the islands are afforded us. The Araliaceæ are said to have fleshy fruits or drupes more or less succulent. The Rubiaceæ have usually berries or drupes, while one genus, Kadua, has "small, flat, winged seeds." The two largest genera of the Labiatæ are said to have "fleshy nucules," which would no doubt be swallowed by birds.130

Antiquity of the Hawaiian Fauna and Flora.—The great antiquity implied by the peculiarities of the fauna and flora, no less than by the geographical conditions and surroundings, of this group, will enable us to account for another peculiarity of its flora—the absence of so many families found in other Pacific Islands. For the earliest immigrants would soon occupy much of the surface, and become specially modified in accordance with the conditions of the locality, and these would serve as a barrier against the intrusion of many forms which at a later period spread over Polynesia. The extreme remoteness of the islands, and the probability that they have always been more isolated than those of the Central Pacific, would also necessarily result in an imperfect and fragmentary representation of the flora of surrounding lands.

Concluding Observations on the Fauna and Flora of the Sandwich Islands.—The indications thus afforded by a study of the flora seem to accord well with what we know of the fauna of the islands. Plants having so much greater facilities for dispersal than animals, and also having greater specific longevity and greater powers of endurance under adverse conditions, exhibit in a considerable degree the influence of the primitive state of the islands and their surroundings; while members of the animal world, passing across the sea with greater difficulty and subject to extermination by a variety of adverse conditions, retain much more of the impress of a recent state of things, with perhaps here and there an indication of that ancient approach to America so clearly shown in the Compositæ and some other portions of the flora.

General Remarks on Oceanic IslandsWe have now reviewed the main features presented by the assemblages of organic forms which characterise the more important and best known of the Oceanic Islands. They all agree in the total absence of indigenous mammalia and amphibia, while their reptiles, when they possess any, do not exhibit indications of extreme isolation and antiquity. Their birds and insects present just that amount of specialisation and diversity from continental forms which may be well explained by the known means of dispersal acting through long periods; their land shells indicate greater isolation, owing to their admittedly less effective means of conveyance across the ocean; while their plants show most clearly the effects of those changes of conditions which we have reason to believe have occurred during the Tertiary epoch, and preserve to us in highly specialised and archaic forms some record of the primeval immigration by which the islands were originally clothed with vegetation. But in every case the series of forms of life in these islands is scanty and imperfect as compared with far less favourable continental areas, and no one of them presents such an assemblage of animals or plants as we always find in an island which we know has once formed part of a continent.

It is still more important to note that none of these oceanic archipelagoes present us with a single type which we may suppose to have been preserved from Mesozoic times; and this fact, taken in connection with the volcanic or coralline origin of all of them, powerfully enforces the conclusion at which we have arrived in the earlier portion of this volume, that during the whole period of geologic time as indicated by the fossiliferous rocks, our continents and oceans have, speaking broadly, been permanent features of our earth's surface. For had it been otherwise—had sea and land changed place repeatedly as was once supposed—had our deepest oceans been the seat of great continents while the site of our present continents was occupied by an oceanic abyss—is it possible to imagine that no fragments of such continents would remain in the present oceans, bringing down to us some of their ancient forms of life preserved with but little change? The correlative facts, that the islands of our great oceans are all volcanic (or coralline built probably upon degraded volcanic islands or extinct submarine volcanoes), and that their productions are all more or less clearly related to the existing inhabitants of the nearest continents, are hardly consistent with any other theory than the permanence of our oceanic and continental areas.

We may here refer to the one apparent exception, which, however, lends additional force to the argument. New Zealand is sometimes classed as an oceanic island, but it is not so really; and we shall discuss its peculiarities and probable origin further on.

CHAPTER XVI

CONTINENTAL ISLANDS OF RECENT ORIGIN: GREAT BRITAIN

Characteristic Features of Recent Continental Islands—Recent Physical Changes of the British Isles—Proofs of Former Elevation—Submerged Forests—Buried River Channels—Time of Last Union with the Continent—Why Britain is poor in Species—Peculiar British Birds—Freshwater Fishes—Cause of Great Speciality in Fishes—Peculiar British Insects—Lepidoptera Confined to the British Isles—Peculiarities of the Isle of Man—Lepidoptera—Coleoptera confined to the British Isles—Trichoptera Peculiar to the British Isles—Land and Freshwater Shells—Peculiarities of the British Flora—Peculiarities of the Irish Flora—Peculiar British Mosses and Hepaticæ—Concluding Remarks on the Peculiarities of the British Fauna and Flora.

We now proceed to examine those islands which are the very reverse of the "oceanic" class, being fragments of continents or of larger islands from which they have been separated, by subsidence of the intervening land at a period which, geologically, must be considered recent. Such islands are always still connected with their parent land by a shallow sea, usually indeed not exceeding a hundred fathoms deep; they always possess mammalia and reptiles either wholly or in large proportion identical with those of the mainland; while their entire flora and fauna is characterised either by the total absence or comparative scarcity of those endemic or peculiar species and genera which are so striking a feature of almost all oceanic islands. Such islands will, of course, differ from each other in size, in antiquity, and in the richness of their respective faunas, as well as in their distance from the parent land and the facilities for intercommunication with it; and these diversities of conditions will manifest themselves in the greater or less amount of speciality of their animal productions.

This speciality, when it exists, may have been brought about in two ways. A species or even a genus may on a continent have had a very limited area of distribution, and this area may be wholly or almost wholly contained in the separated portion or island, to which it will henceforth be peculiar. Even when the area occupied by a species is pretty equally divided at the time of separation between the island and the continent, it may happen that it will become extinct on the latter, while it may survive on the former, because the limited number of individuals after division may be unable to maintain themselves against the severer competition or more contrasted climate of the continent, while they may flourish, under the more favourable insular conditions. On the other hand, when a species continues to exist in both areas, it may on the island be subjected to some modifications by the altered conditions, and may thus come to present characters which differentiate it from its continental allies and constitute it a new species. We shall in the course of our survey meet with cases illustrative of both these processes.

The best examples of recent continental islands are Great Britain and Ireland, Japan, Formosa, and the larger Malay Islands, especially Borneo, Java, and Celebes; and as each of these presents special features of interest, we will give a short outline of their zoology and past history in relation to that of the continents from which they have recently been separated, commencing with our own islands, to which the present chapter will be devoted.

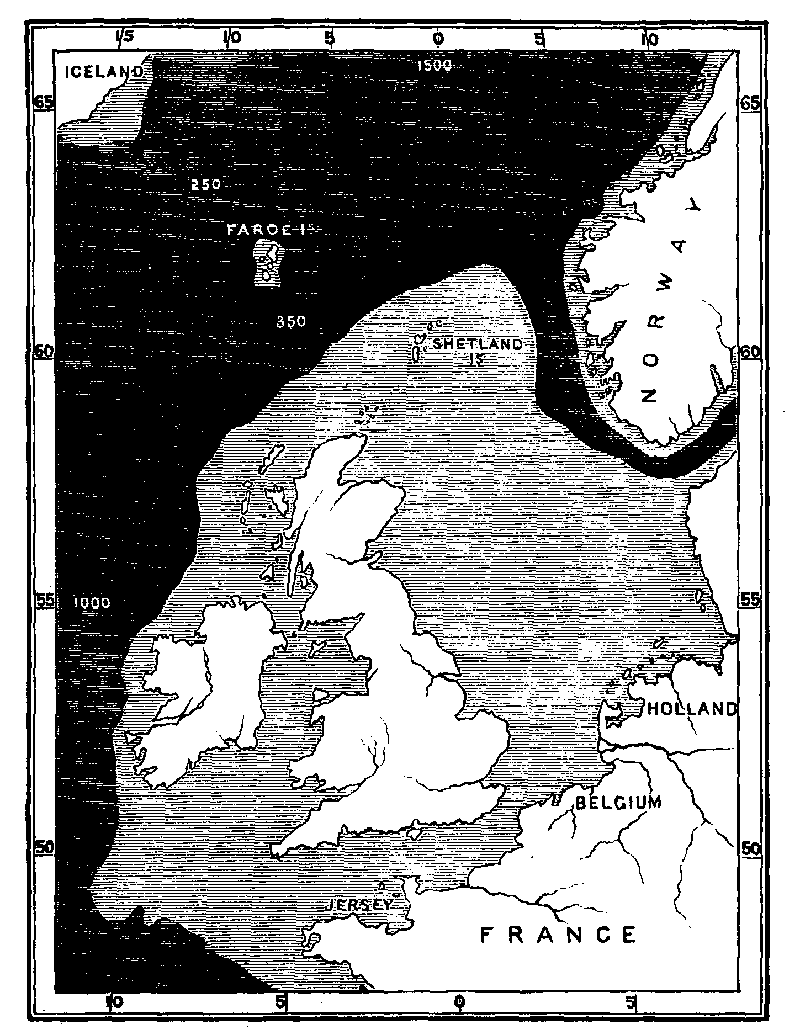

Recent Physical Changes in the British Isles.—Great Britain is perhaps the most typical example of a large and recent continental island now to be found upon the globe. It is joined to the Continent by a shallow bank which extends from Denmark to the Bay of Biscay, the 100 fathom line from these extreme points receding from the coasts so as to include the whole of the British Isles and about fifty miles beyond them to the westward. (See Map.)

MAP SHOWING THE SHALLOW BANK CONNECTING THE BRITISH ISLES WITH THE CONTINENT.