Полная версия:

Lost in Shangri-La: Escape from a Hidden World - A True Story

Inhabited by humans for more than forty thousand years, New Guinea passed the millennia largely ignored by the rest of the world. Lookouts on European ships caught sight of the island early in the sixteenth century. In 1545, the Spanish explorer Yñigo Ortiz de Retez named the island Neuva Guinea after an African country 16,000 kilometres away, because the natives he saw on the coast had black skin. For another two centuries, New Guinea was left mostly to itself, though trappers stopped by to collect the brilliant plumes of its birds of paradise to make hats for fashionable Sri Lankan potentates. In the eighteenth century, the island became a regular landing spot for French and British explorers. Captain Cook visited in 1770. Scientists followed, and the island drew a steady stream of field researchers from around the globe searching for discoveries in zoology, botany and geography.

In the nineteenth century, New Guinea caught the eye of traders seeking valuable raw materials. No precious minerals or metals were easily accessible, but the rising value of coconut oil made it worthwhile to plant the flag and climb the palm trees along the coastline. European powers divided the island roughly in half, and the eastern section was cut in half again. Over the years, claims of sovereignty were made by Spain, Germany, the Netherlands, and Great Britain. Nevertheless, even well-educated Westerners had a hard time finding it on a map.

After the First World War, New Guinea’s eastern half was controlled by Britain and Australia. The island’s western half was controlled by the Netherlands – and was henceforth known as Dutch New Guinea – with Hollandia as its capital. Unprecedented attention was drawn to the island as the Second World War unfolded, because of its central location in the Pacific theatre.

Japan invaded in 1942, planning to use New Guinea to launch attacks on Australia, just over 160 kilometres away across the Torres Straits. In April 1944, US troops executed a daring strike called ‘Operation Reckless’ that scattered the Japanese troops and won Hollandia for the Allies. The Americans turned it into an important base of their own, and General Douglas MacArthur, Supreme Commander of Allied Forces in the Southwest Pacific, built his headquarters there before moving on to the Philippines.

____

In New Guinea as elsewhere, Margaret Hastings and other WACs filled strictly non-combat roles, as expressed by their slogan, ‘Free a Man to Fight’. An earlier motto, ‘Release a Man for Combat’, was scratched because it was feared it might feed suspicions among the WACs’ detractors that their secret purpose was to provide sexual distractions for soldiers in the field. MacArthur was not among those critics. He liked to say the WACs were ‘my best soldiers’ because they worked harder and complained less than male troops. Eventually, more than one hundred and fifty thousand women served as WACs during World War II, making them the first women other than nurses to join the US Army.

Margaret arrived in Hollandia eight months after the success of Operation Reckless. By then, little of the war’s bloody drama was playing out in that corner of the Pacific. Thousands of Japanese troops remained armed and in hiding on the island, but few were believed to be in the immediate vicinity of Hollandia. Nevertheless, sentries patrolled the sea of tents and one-storey buildings on the Army base. WACs were routinely escorted under armed guard, and women’s tents were ringed by barbed wire. One WAC explained that the highest-ranking woman in her tent was given a sidearm to keep under her pillow, with instructions to kill her tent mates then herself if Japanese troops attacked. New Guinea natives also raised concerns, though the ones nearest Hollandia had grown so comfortable with the Americans they would call out, ‘Hey Joe – hubba, hubba – buy War Bonds.’ Australian soldiers who had received help from the natives during battles with the Japanese nicknamed them ‘Fuzzy Wuzzy Angels’.

Some WACs thought the safety precautions’ real aim wasn’t to protect them from enemies or natives, but from more than one hundred thousand US soldiers, sailors and airmen in and around Hollandia. Some of those fighting boys and men hadn’t seen a Western woman in months.

Almost immediately upon her arrival in Hollandia, Margaret became a focus of lovelorn soldiers’ attentions. ‘I suppose you have heard about blanket parties,’ she wrote to a friend in Owego in February 1945. ‘I know I did and was properly shocked. They are quite the thing in New Guinea. However, they are not as bad as they seem and anyway, nothing can be done on a blanket that can’t be done in the back seat of a car.

‘You see, we have no easy chairs and Jeeps are not too easy to sit in. So you just take your beer, or at the end of the month when the beer is all gone, your canteen of water and put it in a Jeep and ride all around until you find some nice place to relax. The nights are lovely over here and it’s nice to lay under the stars and drink beer and talk, or perhaps go for a swim … With the surplus of men over here, you can’t help but find some nice ones. I have had no difficulty along that line at all.’

Far from home, Margaret indulged her adventurous impulses. ‘One night,’ she wrote, ‘six of us went out in a Jeep without any top and drove all over the island. We travelled on roads where the bridges had been washed away, drove through water, up banks, and almost tipped over about ten times.’ The letter didn’t give away military secrets, only personal ones, so it slipped untouched past the base censors.

Margaret’s great friend was a pretty brunette sergeant named Laura Besley. The only child of a retired oil driller and a homemaker, Laura hailed from a small town in Pennsylvania, 144 kilometres from Pittsburgh. She had spent a year in college before enlisting in the WACs in August 1942.

Laura was taller and more full-figured than Margaret, but otherwise the two WACs were much alike. Laura was thirty-one, single, with a reputation among her family for being a ‘sassy’ young woman who did as she pleased.

When they were not working, blanketing or joyriding, Margaret, Laura and the other WACs made their quarters as plush as possible. ‘It is really quite homelike, and I am lucky enough to be in with five exceptionally nice girls,’ Margaret wrote another friend at home. They furnished their 3.5-metre-square canvas home with small dressing tables made from boxes and burlap. They sat on chairs donated by supply officers who hoped the gifts would translate into dates. A small rug covered the concrete pad that was the floor, mosquito netting dangled over their cots, and silky blue parachute cloth hung as decoration from the tent ceiling.

Sergeant Laura Besley of the Women’s Army Corps.

A single bulb illuminated the tent, but a kind lieutenant named John McCollom who worked with Margaret’s boss gave Margaret a double electric socket. The coveted device allowed her to enjoy the luxury of light while she ironed her uniforms at night. Quiet and unassuming, John McCollom was one of a pair of identical twins from Missouri who served together in Hollandia. He was single and could not help but notice Margaret’s good looks, yet he did not try to convert the gift into the promise of a date. His good manners made Margaret appreciate it all the more.

The wildlife of New Guinea was not so unassuming. Rats, lizards, and hairy spiders the size of coffee saucers marched boldly into the WACs’ tents, and mosquitoes feasted on any stray arm or leg that slipped out from under the cots’ protective netting. Even the precautions had vivid side effects. Bitter-tasting Atabrine tablets warded off malaria, but the pills brought on headaches and vomiting, and they turned soldiers’ and WACs’ skin a sickly shade of yellow.

A lack of refrigeration meant most food came three ways: canned, salted, or dehydrated. Cooking it changed the temperature but not the flavour. WACs joked that they had been sent to the far reaches of the South Pacific to ‘Get skinny in Guinea’. To top it off, Hollandia was paradise for fungus. The weather varied little – a mixture of heat, rain, and humidity – which left everyone wet and overripe. Margaret showered at least twice a day using cold water pumped from a mountain stream. Still, she perspired through her khakis during the boiling hours in between. She relied on Mum deodorant, as well as ‘talcum, foot powder, and everything in the books in order to keep respectable’, she wrote in a letter home. ‘It is a continuous effort to keep clean over here. There are no paved roads and the dust is terrible, and when it rains there is mud.’

An American military officer described Hollandia vividly: ‘There was “jungle rot” – all five types. The first three were interesting to the patient; the next two were interesting to the doctor and mostly fatal to the patient. You name it – elephantiasis, malaria, dengue fever, the “crud” – New Guinea had it all. It was in the water in which you bathed, the foliage you touched – apparently the whole place was full of things one should have cringed from. But who has time to think when there are enemy snipers hanging dead, roped to their spotter trees; flesh-eating piranhas inhabiting the streams; lovely, large snakes slithering nearby; and always the enemy.’

Yet there was great beauty, too, from the lush mountains to the pounding surf; from the sound of the wind rustling through the leaves of coconut palms to the strange calls and flamboyant feathers of wild birds. Margaret’s tent was some fifty kilometres inland, near Lake Sentani, considered by its admirers to be among the world’s most picturesque bodies of water. Small islands that looked like mounds of crushed green velvet dotted its crystalline waters. On long work days, Margaret relieved her tired eyes by looking up from her desk to Mount Cyclops, its emerald flank cleaved by the perpetual spray of a narrow waterfall. She described the sight as almost enough to make her feel cool.

Mostly, though, Hollandia was a trial. The WACs’ official history singled out Base G as the worst place in the war for the health of military women: ‘The Air Surgeon reported that “an increasing number of cases are on record for nervousness and exhaustion,” and recommended that personnel be given one full day off per week to relieve “nervous tension.”’

Margaret’s boss took such warnings to heart, and he searched for ways to ease the stress among his staff.

____

Margaret was one of several hundred WACs assigned to the Far East Air Service Command, an essential if unglamorous supply, logistics and maintenance outfit known as ‘Fee-Ask’. Just as in civilian life, Margaret was a secretary. Her commanding officer was Colonel Peter Prossen, an experienced pilot and Fee-Ask’s chief of maintenance.

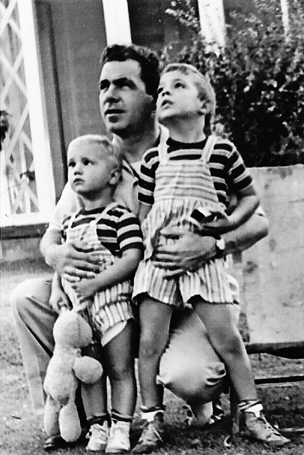

The early hours of 13 May 1945 were quiet in the big headquarters tent at Fee-Ask. Colonel Prossen spent part of the morning writing a letter to his family back home in Texas: his wife Evelyn, and their three young children, sons Peter and David, and daughter Lyneve, whose name was an anagram of her mother’s.

Prossen was thirty-seven, stocky, with blue eyes, a cleft chin, and thick brown hair. A native of New York from an affluent family, he joined the military so he could fly.

Prossen had spent most of his children’s lives at war, but his elder son and namesake knew him as a warm, cheerful man with a love of photography. He would sing ‘Smoke Gets in Your Eyes’ loudly and out of tune while his wife played flawless piano. After visits home, Prossen would fly over their house and tip his wings, to say goodbye.

In a letter to his wife a day earlier, addressed as always to ‘My dearest sweetheart’, Prossen commented on the news from home, counselled her to ignore slights by his sister, and lamented how long it took for photos of their children to reach him. He told her to save the stuffed koalas he had shipped home until their baby daughter’s second birthday. He asked her to watch the mail for a native axe he had sent home as a souvenir.

Colonel Peter Prossen with his sons, David and Peter.

A dozen years in the military hadn’t diminished Prossen’s tenderness to his family. He sent his wife love poems and heart-filled sketches on Valentine’s Day, and he pined for them to be reunited. Despite the harsh conditions he endured in Hollandia, Prossen commiserated sincerely with his wife about the hardships of gas rationing and caring for their children without him there.

The morning of 13 May 1945, for Mother’s Day, he wrote to Evelyn in his cribbed handwriting: ‘My sweet, I think that we will be extra happy when we get together again. Don’t worry about me … I am glad that the time passes fairly quickly for you – hope it does till I get home. Then I want it to slow down.’

Later in the letter, Prossen described a poem he had read about two boys playing ‘make-believe’. It made him wistful for his own sons. Sadness leaked through his pen as he wrote that their son Peter would take his First Communion that very day without him: ‘I’ll bet he is a nice boy. My, but he is growing up.’ Prossen signed off, ‘I love you as always. Please take good care of yourself for me. I send all my love. Devotedly, Pete.’

Lately, Prossen had been anxious about the toll Dutch New Guinea was taking on the hundred or so men and the twenty-plus WACs serving directly under him. He wrote to his wife that he tried to relieve the pressures shouldered by junior officers, enlisted men, and WACs, though he didn’t always succeed. ‘I lose sight of the fact that there is a war going on and it’s different,’ he wrote. ‘My subordinates are also depressed and been here a long time.’ He wanted to show them he valued their hard work.

Prossen wheedled pilots flying from Australia to bring his staff precious treats: Coca-Cola syrup and fresh fruit. Lately, he had been offering even more desirable rewards – sightseeing flights up the coastline. On this day, 13 May 1945, Colonel Prossen had arranged the rarest and most sought-after prize for his staff, one certain to boost morale: a trip to Shangri-La.

Chapter Three The Hidden Valley of Shangri-La

A YEAR EARLIER, IN MAY 1944, COLONEL RAY T. Elsmore heard his co-pilot’s voice crackle through the intercom in the cramped cockpit of their C-60 trans-port plane. Sitting in the left-hand seat, Elsmore had the controls, flying a zigzag route over and through the mountainous backbone of central New Guinea.

Elsmore commanded the 322nd Troop Carrier Wing of the US Army Air Forces. On this particular flight, his mission was to find a place to build a landing strip as a supply stop between Hollandia, on New Guinea’s northern coast, and Merauke, an Allied base on the island’s southern coast. If that wasn’t possible, he hoped to discover a more direct, low-altitude pass across the Oranje Mountains to make it easier to fly between the two bases.

The co-pilot, Major Myron Grimes, pointed at a mountain ahead: ‘Colonel, if we slip over that ridge, we’ll enter the canyon that winds into Hidden Valley.’

Grimes had made a similar reconnaissance flight a week earlier, and now he was showing Elsmore his surprising discovery. On his return from that first flight, Grimes claimed to have found a mostly flat, verdant valley some 150 air miles (240 kilometres) from Hollandia, in a spot where maps showed only an unbroken chain of high peaks and jungle-covered ridges. Mapmakers usually just sketched a string of upside-down ‘Vs’ to signify mountains and stamped the area ‘unknown’ or ‘unexplored’. One imaginative mapmaker claimed that the place Grimes spotted was the site of an ‘estimated 14,000-foot peak’. He might as well have written: ‘Here be dragons.’

If a large, uncharted, tabletop valley really existed in the jigsaw-puzzle mountain range, Colonel Elsmore thought it might make a good spot for a secret air supply base or an emergency landing strip. Elsmore wanted to see this so-called Hidden Valley for himself.

____

On Grimes’s signal, Elsmore pulled back on the C-60’s control wheel. He guided the long-nosed, twin-engine plane over the ridge and down into a canyon. Easing back the plane’s two throttle levers, he reduced power and remained below the billowing white clouds that shrouded the highest peaks. Pilots had nightmares about this sort of terrain. An occupational hazard of flying through what Elsmore called the ‘innocent white walls’ of clouds was the dismal possibility that a mountain might be hiding inside. Few pilots in the Army Air Forces knew those dangers better than Elsmore.

At fifty-three years old, energetic and fit enough to pass for a decade younger, Elsmore resembled the actor Gene Kelly. The son of a carpenter, he had been a flying instructor during the First World War, after which he had spent more than a decade delivering air mail through the Rocky Mountains. With the Second World War looming, Elsmore returned to military service and, when the war started, he immediately proved his worth. In March 1942, Elsmore arranged General MacArthur’s evacuation flight from the besieged island of Corregidor in Manila Bay to the safety of Australia. Later he became director of air transport for the Southwest Pacific, delivering troops and supplies wherever MacArthur needed them in New Guinea, the Philippines, the Dutch East Indies, Borneo, Australia, and the western Solomon Islands.

Colonel Ray Elsmore.

As Elsmore and Grimes flew deeper into the canyon, they could see the walls growing steeper and narrower, steadily closing in on the plane’s wingtips. Elsmore steered around a bend, trying to stay in the middle of the canyon to maximize clearance on both sides of the twenty-metre wingspan. Straight ahead he saw a horrifying sight: a sheer rock wall. Elsmore grabbed both throttle levers. He began to thrust them forward, trying to gain full power as he prepared to veer up and away. But Grimes urged otherwise.

‘Push on through,’ the major said. ‘The valley is just beyond.’

Surveying the situation with only seconds to spare, travelling at more than 320 kilometres per hour, Elsmore chose to trust his twenty-four-year-old co-pilot. He followed Grimes’s instructions, slicing his way over the onrushing ridge and just beneath the overhanging clouds.

Safely in the clear, Elsmore saw a break in the puffy clouds. Spread out before them was a place their maps said didn’t exist, a rich valley Elsmore later called ‘a riot of dazzling color’. The land was largely flat, giving him a clear view of its full breadth – nearly forty-eight kilometres long and in places more than twelve kilometres wide, running northwest to southeast. Much of the valley was carpeted by tall, sharp kunai grass, waist-high in spots, interrupted by occasional stands of trees. Surrounding it were sheer mountain walls with jagged ridges rising to the clouds.

At the southeastern end, a river cascaded over a cliff to enter the valley. More than thirty metres wide in spots, it snaked through the valley, interrupted by occasional rapids before, at the valley’s northwestern end, the cocoa-coloured river disappeared into an enormous hole in the mountain wall that formed a natural grotto, its upper arch some ninety metres above the ground.

Even more remarkable than the valley’s physical splendour were its inhabitants: tens of thousands of people who lived as their ancestors had since the Stone Age.

____

Peering down through the cockpit windows, Elsmore and Grimes saw several hundred small, clearly defined native villages. Surrounding the native compounds were carefully tended gardens, with primitive but effective irrigation systems, including dams and drainage ditches. ‘Crops were in full growth everywhere and, unlike the scene in most tropic lands, the fields were literally alive with men, women, and children, all hard at work,’ Elsmore marvelled.

Men and boys roamed naked except for hollowed-out gourds covering their genitals; women and girls wore only low-slung fibre skirts. As he flew on, mesmerized by the scene below him, Elsmore watched the natives scatter at the sight and sound of the roaring airplane, ‘some crawling under the sweet potato vines and others diving into the drainage ditches’. Pigs wandered around the compounds, and Elsmore caught sight of a few black dogs lazing about.

At the edges of large, open fields, Elsmore noticed spindly towers made from lashed-together poles rising some nine metres or more above the valley floor. Each tower had a platform for a sentry near the top, and some towers had small grass roofs, to shelter the sentries from the sun. Elsmore pushed the control wheel forward, to guide the plane lower for a better look. He guessed, correctly, that they were watchtowers to guard against marauding enemies. As the C-60 flew on, the thrumming noise of its twelve-hundred-horsepower engines bounced off the valley floor and mountain walls. Frightened sentries abandoned their posts, climbed down the towers, and ran to nearby huts. Elsmore saw wooden spears more than four metres long leaning against those huts.

A native village photographed from the air by Colonel Ray Elsmore.

Elsmore snapped a few photographs, focusing on the people and their huts, some of them round like toadstools or thatched-roof ‘igloos’, he thought, and others long and narrow like boxcars. ‘The panorama of these hundreds of villages from the air is one of the most impressive sights I have ever seen,’ he wrote afterwards.

He and Grimes had a mission to complete, so Elsmore pulled back on the control wheel and roared up and out of the valley. He pointed the plane southeast and flew some 320 kilometres to another potential site for a landing strip, in an area called Ifitamin.

____

Several days later, Elsmore wrote a secret memo on his findings to his commanding officer, General George C. Kenney. The memo described the survey flights and paid special attention to the valley and the people in it. Major Grimes had called his discovery ‘Hidden Valley’, but in the memo Elsmore referred to it in less poetic terms. He called it the ‘Baliem Valley’, using the name of the river that flowed through it.

One concern Elsmore expressed to General Kenney about building a landing strip was the reaction of the natives. ‘There is no access into this valley … except by air, and for that reason very little is known of the attitude of the natives. It is known that there are headhunters in many of the adjacent regions and there is a suspicion that the natives in the Baliem Valley may also be unfriendly,’ he wrote. Also in the memo, Elsmore issued an ominous warning to fellow pilots who might follow him there. He described at length how treacherous it could be to fly through the cloud-covered pass into the valley, especially ‘for a pilot unfamiliar with this canyon’.

As it turned out, by any name Hidden Valley or Baliem Valley was unsuitable for a military landing strip. At 1600 metres above sea level, surrounded by mountains reaching 4000 metres and higher, it was too dangerous and inaccessible. Also, there was a better alternative. Elsmore learned that an Australian missionary had found the natives at Ifitamin to be friendly and eager to be put to work. This was more suitable for Elsmore’s plan. ‘Not only were we anxious to avoid incidents and bloodshed’ – believed to be a strong possibility with the natives of Hidden/Baliem Valley – ‘but we wanted to employ native labor on the construction project.’

Although the valley could serve no military purpose, news of its discovery spread quickly around Hollandia and beyond. Interest heightened when Elsmore began telling people that he thought the valley’s inhabitants looked much taller and larger than any other New Guinea natives he had seen. Elsmore’s impressions contributed to fast-spreading stories, or more accurately, tall tales, that Hidden Valley was populated by a previously unknown race of primitive giants. Some called them black supermen – handsome models of sinewy manhood standing over two metres tall. Soon the natives were said to be headhunters and cannibals, savages who practised human sacrifice on stone altars. The pigs the natives raised were said to be the size of ponies. The bare-breasted native women were said to resemble the curvaceous pin-up girls in soldiers’ barracks, especially the exotic, sarong-wearing actress Dorothy Lamour, whose hit movies included The Jungle Princess.