Полная версия:

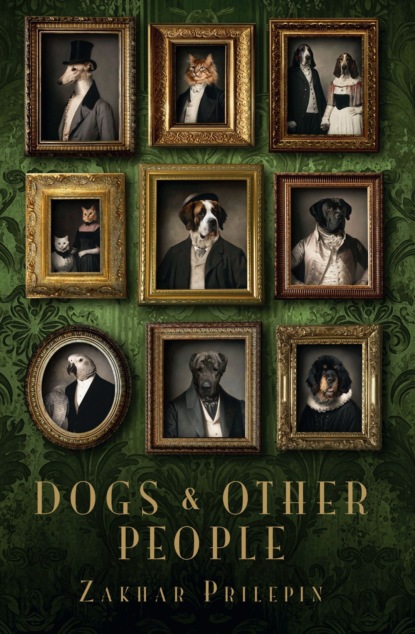

Dogs and other people

With the crutch lying next to her bed she prodded her son.

“Sonny, sonny, sonny,” she repeated hurriedly. “The doctor's here.”

Swearing and waving his hands, forgetting where he had fallen asleep, Alyoshka got up and stood there for a while, stretching his arms.

Finally realizing where he should step to turn on the only lamp in the house, he waited for a minute in the weak light, listening to his mother's pitiful whispering.

Finally, he shifted the door – and in the darkness he saw the puppy that he had been drowning for so long, only this puppy had grown and was now enormous.

Shmel prodded Alyoshka with his shaggy head – and Alyoshka dropped to the ground.

In his hurry to get in, Shmel stepped on Alyoshka's stomach, head and other places.

Overcoming this annoying obstacle, Shmel immediately jumped over to Alyoshka's mother on the old bed, knocking over a stool on the way with expired medicine on it.

Taking a place by the wall, he looked fixedly at Alyoshka's mother.

His powerful tail rhythmically slapped the wall.

Suddenly she laughed.

Rubbing the snow off his face, Alyoshka sat down – and suddenly he remembered that the last time his mother had laughed like this was when he was 12 years old. They had been gathering berries.

* * *The Blind ones, who bred goats, were waiting for a new addition to the family all through the second half of December – goat kids.

Every new kid, especially at New Year, was a source of joy for them. The kids were silky to the touch when they were born. They trusted the world, smelt of warmth and happily wagged their tails, sucking on their mother's udder.

On the night before New Year's Eve, the wife ran out several times to see how things were going., The mother goat was anxious, and looked at her with a direct, shaming gaze, and her sides were swelling – but by midnight she still hadn't given birth.

In the depth of the night they heard a noise in the barn.

“She's given birth!” the wife said in a confident whisper. “Our girl.”

Taking a torch, a little warmed by the liqueur they had drunk, they raced to see the mother.

They also had four goat kids, two male and two female, and fierce adult he-goat.

The husband could distinguish all his animals by the sound of their movement, and as he approached them he realized: the senior goat who was running from one corner of the pen to the other was not just excited, he was very scared.

The wife opened the door and screamed. She almost dropped the dim torch.

For the first time in her life, she managed to think about three things at once: the mother goat had given birth to the wrong kind of animal, the liqueur had been too strong, and this was the right time to cross herself, but the torch was in the way.

The husband, owing to his lack of vision, was not capable of being so scared.

Despite his blindness, he knew the positions of everything in his household. With an even movement he correctly found the switch and flicked it. The light came on.

As he listened, the husband realized that nothing so terrible was happening – all the animals were breathing, and so there had not been any killing: everything else seemed to be fixable to him.

“What's there?” he asked calmly.

The wife sighed and said:

“Lord… It's a dog. It's enormous. How did it get here?.. And the goat kids have been born… How do I get to them now…”

Shmel lay on the hay among the goats.

They were already used to him, and did not feel any menace from his presence. The male goat had first tried to butt him, but Shmel didn't mind and wasn't bothered. After a while the goats lay down next to the dog.

Shmel adored having someone warm lying and breathing next to him.

There was also a wonderful smell: milk, dung and new life.

Seeing the owners, he raised his head and waved his tail twice, as if asking a question.

“I'm not in the way, am I?” he seemed to be saying. “Don't worry, I'm looking after everyone…”

Every time his tail swept across the barn floor there was a rustling of dirty straw.

* * *The grandchildren, although they were not blood relations, genuinely wanted to take their lonely ancient grandfather to town on every major holiday. He always refused.

On the last day of December, the grandfather heated the stove in the morning. In the evening he drank an infusion of summer herbs. He licked the wooden spoon with the honey stuck to it, long and carefully. He looked out the window, remembering that somewhere the first star would appear, which he could no longer see.

He climbed on the stove and waited for death.

Over the year death did not arrive, but perhaps it observed the calendar – and now it was visiting everyone whose documents in the general register were outdated or lost.

Until November the grandfather slept with the window open and did not fear the cold, but on New Year's Eve, to ensure that death would not encounter any obstacles, he left the door ajar, imagining what form it would take.

The grandfather did not believe that death looked like an old woman clutching a scythe. He was an old man himself – and how exactly could an old woman scare him, if he had outlived countless numbers of them in his life?

Half a century ago there was an old woman living in every hut, and the grandfather had buried all of them. The old women had daughters, and he had also buried many of them. Now the time of the granddaughters, but the grandfather no longer counted them.

Even if they all gathered together – how could he be scared of them?

Death came at night and turned out to be a bear.

The old beekeeper was the only resident in the village who had never seen Shmel before, and could not recognize him because of his poor vision. Especially as he had never seen such a huge dog before.

The bear sniffed around the stove and looked for something living.

Shmel sensed that there was a living soul present here, although it was barely warm.

The grandfather opened his sunken mouth and said:

“I am here.”

The bear got excited, and of course in his joy he knocked all the ladles and cups off the table.

“How about that,” the grandfather thought with satisfaction. “Death is happy”.

* * *In the morning Nikanor Nikiforovich went outside to have a smoke.

He had not felt bored alone for a long time. People oppressed him.

Sometimes in the winter evenings Nikanor Nikiforovich suddenly felt a tingling impulse of tenderness towards his close and distant relatives. But after thinking things over and remembering all of true nature of these people, just as drastically, without any transition, he started to get angry.

The forest began near our house and ended three days away.

Today, after having a little drink, he began to miss having someone to talk to only in the small hours of the morning. Not that Nikanor Nikiforovich was tormented by the urge to pour out his soul – no. He needed a real person for about seven minutes, say: one smoke was enough.

Tormented by insomnia, Nikanor Nikiforovich certainly did not expect to encounter anyone at dawn, but this time he was wrong.

Shmel was sitting on his porch and watching the snow fall.

“Oh,” said Nikanor Nikiforovich, unsurprised: he was a hunter, and had often come face to face with a beast.

“Wait, I'll bring a glass,” he said.

A minute later Nikanor Nikiforovich returned with a glass and a board with generous cuts of bacon mixed with onion.

“You don't want any onion,” he said reasonably. “But I do. Well then, Happy New Year, what's your name… Shmel… What a name for a dog. Here you go. What a mouth you've got.”

…Taking the same path with which he left our yard, our dog returned home – and fell asleep.

That January we learned that Shmel had enjoyed the celebrations in enviable fashion – he had left on time and without causing irreparable damage.

But what's more, he had also gone back the next day – which is hardly the usual practice in the best celebrations.

…Once again he went around the entire village at night on New Year's Day.

This time he was expected – and he was fed even more inventively.

On the following days he repeated his visits, and if the house was locked and everyone was asleep, Shmel didn't get too upset, but promised to return the next day.

* * *On the first Sunday of January, Alyoshka took his mother to the very heart of the village, where our three lanes met and a heavy red bell hung on a post.

His mother sat on an amazing gurney: an old chair insulated with a colorful fur blanket with wide slides attached to the bottom and firm handles to the back.

It was Nikanor Nikiforovich who made this cross-country vehicle, although he had never made anything like it for anyone in the village before.

By coincidence, our family was taking Shmel for a walk just at that moment.

Surprised by the unexpected appearance of Alyoshka's mother – who was in fact a young woman, and who was not just smiling, but even waving her hand with a multi-colored glove on – we stopped in our tracks.

Alyoshka was slightly tipsy, but nimbly maneuvered the chair on skies. He loudly shouted orders, and answered them himself.

From the other side of the village the prosecutor and his wife appeared, warmly dressed for the weather. It was clear that they were moving towards us.

From the forest, along a well-trodden path, with deliberate steadiness, came Ekaterina Eliseevna's daughters, each one pulling the other.

Half a minute later we also saw their mother. She was in a hurry, adjusting the falling scarf on her sweaty face. She looked as if there was a serious discussion in store for us all.

We felt rather uncomfortable, although we did not know why we were to blame.

“We beat out a path with Shmel!” one of the daughters informed us from the distance.

“Shmel was the first, and we followed him, and beat out the path,” the second confirmed.

I smiled on one side of my face and looked at my wife.

She shrugged: “Well then. Poor Ekaterina Eliseevna.”

It was time to go before the discussion could get started, but then the Blind ones appeared in our field of vision, also heading in our direction.

“Shmel ate all my medicine,” Alyoshka's mother informed us cheerfully, almost running right into us after Alyoshka gave another tug on the sled.

“I feel a lot better without it,” she said.

My wife smiled on one side of her face and looked at me.

I shrugged, the way a person does when something falls down the back of his shirt.

The prosecutor and his wife smiled warmly at the people gathered as they approached. Somewhat bashfully, the prosecutor gave my wife a fine-looking jar which sounded like it was full of sweets when shaken.

“Vitamins,” he said. “I bought them in London. For large dogs. We don't have dogs that are that large. But when Shmel sleeps on our rug, he takes a long time to work out what legs to stand on when he wakes up. His joints might start to give him some trouble.”

“On your rug?” I asked indifferently.

“Yes, on our rug, in the hall,” the prosecutor's wife joined in amiably. “He always sleeps there. It's an Indian rug. We didn't let any dogs into the house. My husband is absolutely against it: the hair, the smell… But your dog is like an addition to this rug. We don't even notice him sometimes – we're so used to him!”

The prosecutor moved a slow and, it seemed to me, brooding gaze to his wife.

The Blind ones, who had finally reached us, shouted loudly and almost in unison:

“Congratulations! Shmel has become a godfather! For two he-goats and a she-goat. They take after him.”

“…and here comes the beekeeper…” I thought dispassionately. The ancient man was firmly moving in our direction.

Ekaterina Eliseevna, from somewhere under her fur coat – evidently she was keeping it warm – took out a bundle that was dripping with butter and steaming hot.

“Pancakes. His favorite,” and gave them to my wife. “He can eat 40 in one sitting,” she added and nodded to me tenderly.

My wife looked at me again.

I shrugged again: yes, I like pancakes, what's wrong with that?

Ekaterina Eliseevna's daughters sat down on each side of Shmel, expecting an invisible photographer to capture the moment.

Meanwhile, as if in search of someone, the beekeeper walked through us as if he were walking through trees. After taking several steps, he suddenly stopped and said loudly and happily:

“Tricked me! Shaggy! Head!”

* * *Nikanor Nikiforovich had put a winter spread out on the bonnet of his car. Boiled eggs, goat's cheese, a bottle of horseradish-infused vodka, in which a vortex formed if you shook it, and existence was born.

From the vortex, we emerged – the same as in life – but having acquired forms more adequate to our secret essence.

Ekaterina Eliseevna moved easily in a circle, like a tumbleweed – but if you came close to her, her kind face suddenly flashed like the sunniest and most buttery pancake.

Two clueless and perpetually frightened chickens ran after her, leaving clumsy footprints in the snow.

The prosecutor was very tall – he walked at the level of the sharp-tipped pines, and although his wife was several times smaller than him, this did not stop them from walking together.

Sometimes he took her in his arms, carrying her across snowdrifts.

The old beekeeper, breaking time like an eggshell, entered our reality and left it, as though he was playing a bleak game of hide and seek with someone. The cracks he left soon grew back, and the snow that flew after the beekeeper broke weakly on the barrier that arose.

A minute later the old man appeared in another place.

The Blind ones walked with enormous eyes, in which clouds flowed. Their eyes were so huge that the remaining human structure of these people seemed both indistinguishable and unimportant.

They were followed by goats, also with large eyes. The goats deliberately made fun of their owners, parodying their enchanted appearance with surprising accuracy. When their owners turned around the goats pretended to be chewing grass, although there was no grass around them: it was winter.

Alyoshka rolled his unrelenting pain up into a huge snowball and gave it a nose with a black piece of beetroot. His mother pulled her chair around this ball, on which the doctor sat haughtily.

Shmel, just like the shmel he was named for, hovered above the village, remaining just a sound, and then unexpectedly coming into focus, so that people would not lose faith in miracles and other obstinate revelations.

* * *The next day we cleared the snow in the yard, certain that Shmel would no longer be able to run away at night by jumping on the roof.

Not despairing, during the night the dog dug a hole under the fence – and escaped to the other side.

When I looked into this pit in the morning, once more I was amazed by his incredible strength. Digging this passage through frozen soil to fit his enormous body, he made black powder out of icy ground that could not be broken with a crowbar.

In those years we were still poor and couldn't afford a stone fence.

Feeding Shmel remained a burden for us.

Every day we boiled up an enormous pot of food, throwing potato peelings, a few onions, carrots, some cereal, pasta and perhaps an egg and all kinds of leftovers, and meat – for example chicken gizzards – into an oily stock. In any case it was as if we were taking food from the children, who would have eaten it themselves.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «Литрес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на Литрес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Примечания

1

A bumblebee in Russian.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Для бесплатного чтения открыта только часть текста.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Полная версия книги

Всего 10 форматов