Полная версия

Полная версияEverything Begins In Childhood

What she beat out was even longer but more interesting. I heard a tune in it. I repeated it…

The curly-headed woman smiled. She turned around – I saw that there was another woman taking notes.

“Well done,” she said. “What’s your name? Valery? Well done, Valery. Would you like to study music? Call your mama…”

Mama was told that I had perfect rhythm, that I was admitted and that classes would start in a few days.

“Do you have a piano?” Mama was asked.

Not only didn’t we have a piano, but even paying the school ten rubles a month was a problem for our family. However, we found a way. There was a family in our building that allowed me to use their piano. Their daughter Lena had been studying music for a few years. She was about three years older than I, and I learned my scales and exercises with her help twice a week. Sometimes Lena’s mother, who was a professional musician, joined us and played something for her and our pleasure. That’s how my journey into the amazing world of music began. And I quickly grew fond of that world.

After ceding her seat at the piano to her mama, Lena stood behind her and put her hands on her mama’s shoulders. She moved her head to the rhythm of the tune and sometimes sang along very quietly. I listened and enjoyed it. No matter what Lena’s mother played – Beethoven sonatas, Chopin mazurkas and polonaises – I enjoyed everything, and the way she played. A wide shaft of light coming through the window fell on the keys and lit the pianist’s long nimble fingers. Shadows moved along the keys, “echoing” the music. All that together – the sound of the music, her fingers, the light and shadow on the keys – was magic.

I studied with pleasure, diligently, perhaps owing to that musical family. I received A’s and was praised, but unfortunately it didn’t last long, just about a year. Lena’s father, who was an army officer, retired and decided to move to Moscow. I was left without a piano and the friends who had been my patrons. I missed them, was lost and gave up my music studies soon after, though four years later, my parents talked me into going back to the music school. Strange as it might seem, everything that hadn’t required any special effort before came with great difficulty then. That annoyed me. Music lessons ceased to be festive occasions, and I left the school again, this time for good.

Fortunately, I still had a bent for music. Modern tunes and performers, famous rock groups captivated me. I didn’t even recall my unsuccessful “musical career.” I remembered it for the first time as I stood at the piano listening to the way Ella played.

* * *I was excited and happy all the way home. I was looking forward to future encounters with Ella, with Zoya’s help, of course. Even though Sveta told me as we were leaving, “Come visit us, Valery,” I wasn’t ready to go by myself. I would have done it with Zoya… I hoped that we would visit that cozy little house together before she went away. And then, I might visit them on my own.

* * *But everything turned out differently.

The next day when I returned from school, I found Zoya in the bed in my parents’ bedroom. No one was at home. Mama and Father worked in the morning. Zoya must have started feeling bad while they were away. Her breathing was hard, and she was wheezing. Her chest rose and fell with difficulty, just as Father’s did during his fits. Yes, she was having an asthma attack. And I remembered that Zoya had once talked with Father about that damn asthma. But it turned out that she also had a bad heart. She lay there, pressing her hand to the left side of her chest. Her face was as pale as the pillow.

“Ambulance…” Zoya whispered. I rushed to the phone.

The ambulance (“Quick aid” in Russian) took a very long time to arrive, and Zoya’s breathing was getting harder and harder. She continued rubbing the left side of her chest. I was seized by fear. What if she died?

Perhaps Zoya sensed it, and maybe her kindness was greater than her fear about her condition for she suddenly asked, “Did you… write down… Ella’s phone number? Call… her… by all means… She’s a nice girl…”

* * *Zoya spent a few days at the hospital, and as soon as she felt a little better, she went home to Samarkand.

I ended up not calling Ella. I kept putting it off. I couldn’t bring myself to do it. Zoya, on whom I relied, was no longer around, so I got cold feet.

However, don’t we quite often do things that we regret years later? If I strain my memory, I can recall quite a few others besides not calling Ella…

* * *I saw Zoya again a few years later when, right before our departure for America, Mama and I went to Samarkand to visit the graves of Grandpa Hanan and Grandma Abigai to bid them farewell.

And we visited the Koknareyevs, of course.

We went early in the morning, and no one greeted us. The door to the apartment was open.

An old woman sat on the bed in the living room, combing her long grey hair.

“Come on in, come in,” she said, smiling as soon as we approached the door. Yes, she was smiling and looking at us with her very clear eyes though we knew that she was blind, totally blind.

“Opa, it’s me, Ester,” Mama said.

“We were expecting you. Is Valery with you? I heard the steps… Sit down, sit down. Vera, we have visitors. Where are you?” She said everything so merrily, and her voice was so tender.

Vera, Zoya’s sister, tall, good-looking and also merry, ran into the living room. Zoya who had been out shopping returned almost immediately. Hugging and questions followed. Then we had tea and talked for a long time, naturally, most of all about us and our departure. I felt so nice at their place; it was so easy to breathe there. A breeze that blew slightly through the open door from the yard seemed especially gentle and mild. Now, my idea about how the life of Zoya, her sister and their mother was hopeless seemed utterly unreasonable to me. The three of them were actually very happy.

I suddenly understood that, saw it from a different perspective, and my opinion changed. As Mama and I were returning home from the Koknareyevs’, I pondered how one’s perception of another person’s life could be quite wrong. Given an opportunity to have a closer look at it, you could learn something quite different… That’s how I learned about their life that day.

Later, when we were already living in America, we learned that Zoya’s mother had passed away soon after our visit, and Zoya had departed this world soon after her. She was only forty-two.

Chapter 61. Hebrew Lessons

“Alef, bet, vet, gimmel…”

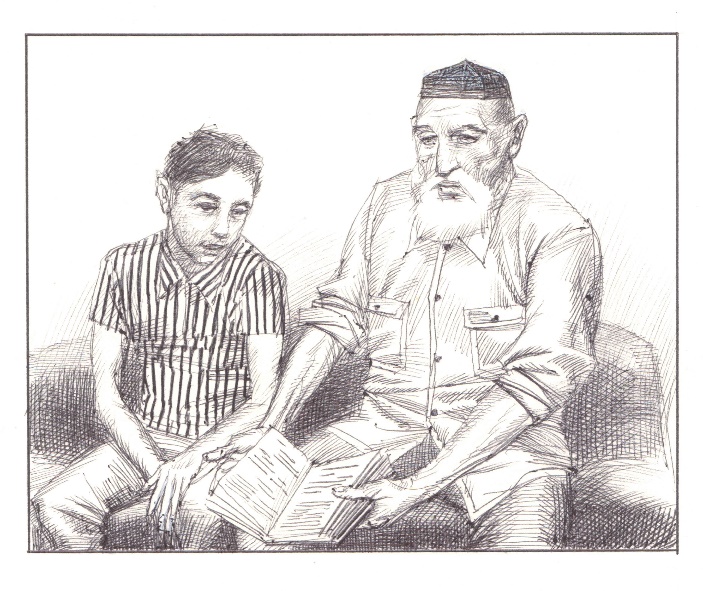

Grandpa and I sat at the table set for breakfast. The choyi kaimoki smelled delicious, and Grandpa, bent over his bowl, munched so appetizingly that my mouth was constantly watering as I pronounced the letters of the difficult Jewish alphabet rather indistinctly. It was Grandpa’s idea to teach me while he was having breakfast. He assumed that I could have breakfast later, but he had to leave for work. If he didn’t have a better time to do it, he shouldn’t have started the whole thing at all. However, it had been my fault.

“Alef, bet, vet, gimmel…”

Grandpa bent his ear with his fingers and inclined toward me, thus demonstrating his attitude about my pronouncing the letters so softly and incorrectly, without due respect for “the sacred language.” That’s how Grandpa always called Hebrew. You say you don’t hear – so take this! “Gimmel!” I yelled at the top of my lungs.

* * *So how did it happen? Why did I agree to have lessons in a language I was absolutely not interested in? Not just the language but reading for Grandpa, who himself didn’t know Hebrew. He could read, but he didn’t understand the meaning of what he read. However, I think the fingers on both hands would be sufficient to count the Jews in Tashkent and Central Asia who were actually fluent in Hebrew in those years. And there weren’t even very many people who could just read Hebrew, like Grandpa. It wasn’t surprising that Grandpa was quite satisfied with what he knew. And if he was reproached for not understanding the subject matter of the prayers, he answered with conviction, “One doesn’t need to understand but rather to feel.”

Yura and I made fun of this quite a lot, but the day eventually came when both of us began to learn Hebrew exactly the same way.

Yura was the first. He was twelve, and, to my great surprise, I heard that my cousin was getting ready to be bar mitzvahed. That’s why he studied Hebrew with a teacher.

Of course, I knew what a Bar Mitzvah was. After all, I was growing up among Jewish relatives. I knew that when a Jewish boy turned thirteen, he became an adult and had to observe Jewish law, the commandments. Bar Mitzvah means “Son of Commandments.” However, at that time, we thought that Bar Mitzvah was the name of the ceremony, of the celebration. Even now many people think that way.

When I learned that Yura was getting ready for that solemn ritual, I was terribly amused. Yura was so childish he couldn’t sit still for a second, and he would be called a Bar Mitzvah. That was very funny. Did this fidgety prankster really study with a teacher? Did he really sit face to face with him and study diligently? It couldn’t be true! He was always doing something foolish, even in class at school. And no teacher would tolerate him at home; he would run away and not look back.

When I went to Tashkent during my fall vacation, I rushed to see Yura right away… He would be the first to welcome me in Grandpa’s yard, but, to my great distress, Yura no longer lived there. There had been a fire in their house at dawn one day in early spring. It had begun when everybody was still asleep. Unfortunately, Uncle Misha was out of town at the time. By some miracle Valya and the kids had managed to escape. Firefighters in Tashkent are not known for their speed and skill. As it had taken them time to arrive and connect the water, the house burned down with almost all their belongings inside. Made homeless by the fire, they had had to find a different place to live.

Now, during summer vacation we didn’t spend all our days from morning till night together. As it happened, we wouldn’t see each other for days in a row. Still, we had a nice summer together. Yura, as always, was tireless when it came to concocting activities and daring pranks.

However, this time I was in for a surprise. When I arrived, Yura sat at the table studying. An open prayer book and some neatly rolled tefillin were in front of him. That was amazing! But most unusual was how serious Yura was, on account of the forthcoming ritual. You really should have seen how proudly he demonstrated his achievements to me.

I had to admit that Yura read fairly well, as far as I could judge. But to praise each other for our academic achievements and good behavior was definitely against our rules. And I began to joke about Yura’s private parts, which were growing in full view. I asked him whether his teacher sat at the table or under the table and who beat whom with a stick. I also remembered to remind him about his inability to sit still for a second. To make fun of each other was our regular custom. Yura could become enraged and work himself up for a fight, which happened quite often. Today, this was a different Yura in front of me. He didn’t jump up; he didn’t start to yell. He didn’t throw a prayer book or anything else at me. He looked at me as if I were a little boy and he an adult. He smiled scornfully and shrugged his shoulders:

“You simply envy me because no one celebrated your Bar Mitzvah.”

I don’t remember what I answered, but I felt I had suffered a defeat.

It was true, my Bar Mitzvah was not celebrated, and my thirteenth birthday, in general, had not been considered a special event.

Probably, our family was the most distant from Jewish tradition, the most assimilated among all our relatives. Was it Uzbek? No, Russian, more likely. And that wasn’t surprising since we lived in Chirchik, a multiethnic city that was largely Russified. Mama cooked non-kosher: we ate lard and mixed our tea and dinner dishes. Saturday at our home was a normal day. We didn’t observe Jewish holidays. And I had Russian, Uzbek, Tatar and Tadjik boys among my friends. But Yura wasn’t just my friend; we were also related by blood. In a word, if I sometimes felt I was a Jew it was only due to the fact that I was reminded about it from time to time. And it was done rudely, and it hurt, as I’ve already written about.

When I grew up, I became more sensitive, not only to insulting nicknames but also to some small things that happened.

Once, while I was visiting Edem and Rustem, their mother addressed them in Tatar, with me around. Did it mean she wanted to tell them something in confidence? That was impolite. It also emphasized that I was of a different ethnicity. It hurt. Though I remembered right away that my relatives did the same when they talked confidentially in our language to me.

As you know, the basis of our language is Tadjik. But Bucharan Jews, having altered it slightly, consider it their own. That’s what they think. But once, after a Tadjik boy I knew heard my mama say something to me in Bucharan Jewish, he asked me, “Tell me, do you have your own language?” “Yes, this is our language,” I answered, surprised. He shook his head and objected, with a trace of reproach, “This is Tadjik, you see? And you are Jews.”

It seemed a little thing, but I was hurt again, even though I almost never spoke that language: we boys all spoke Russian among ourselves. Russian was also heard at home.

The time had come when the “Jewish issue” began to engage me more than before. Conversations about people leaving for Israel were heard more often. It wouldn’t be that bad if it happened to strangers, to people we didn’t know well. One of our relatives, Yura’s grandfather on his mother’s side, had left. And here, at last, the preparations for Yura’s Bar Mitzvah had begun.

On that day, I left him with strange feelings of resentment, envy and even anger. I didn’t know which of them was strongest. Just imagine, he seriously thought that he would become an adult at the age of thirteen. And I was already fifteen! Just look at him! He had already managed to learn to read in Hebrew. Hadn’t my Grandpa said to me hundreds of times in the last few years, “Let me teach you. You read books in Russian all the time, but you don’t know your own sacred tongue.”

That’s why I changed my mind. That evening I told Grandpa, “All right, let’s begin…”

* * *The “sacred tongue” didn’t come easily to me. I knew two alphabets: Cyrillic and Roman, for I studied German at school. Both of them just naturally fit into my head simply and easily. And here were these letters you had to read not from left to right but from right to left while also paying attention to the dots: it turned out that dots replaced vowels. Gosh! And some people swear that Russian is one of the most difficult languages!

I later came to understand that the notions “difficult” and “easy” are very relative. A Chinese child, for example, masters the characters, and they are more difficult than the Hebrew alphabet. But those comforting thoughts didn’t enter my mind at that time.

Our lessons began. After he finished his morning prayer, Grandpa sat down next to me on the couch, adjusting his tefillin to the box. The wrist of Grandpa’s left hand was covered with deep furrows from the small strap since he wound it very tightly around his hand. The creases wouldn’t smooth out quickly since old hands swell up. Holding the prayer book in his furrowed hands, Grandpa passed his twisted finger over each line, from right to left, and pronounced the letters loudly, those same letters: alef, bet, vet and so on. After he was finished, he told me, “Repeat.” I repeated, cocking my eyes at the prayer book, which had the Russian transcription by each Hebrew letter.

By the way, only I could understand the transcription: Grandpa couldn’t read Russian. I didn’t know how he had learned to read. He most likely remembered how to pronounce the letters, syllables and words by rote. And he remembered everything perfectly – he could say a prayer without stopping. Well, and I was peeking. Grandpa got angry, “Why are you peeking? Listen and memorize!” He put his legs together, placed the book on his knees and covered the Russian transcription with his hand. Now, we repeated the letters together because I would constantly forget how to pronounce them. Grandpa naturally got angry again. I began to cheat, speaking very quietly so Grandpa couldn’t hear. He would ask me again and again, holding his ear with his hand, and at that moment I could peek at the transcription. If I remembered correctly, I yelled at the top of my lungs, and Grandpa said approvingly “hosh” which meant “all right, good” in Uzbek, also one of our native tongues.

When we switched from the alphabet to syllables, it turned out that those pages didn’t include transcriptions. I had to memorize by rote as Grandpa read for there was nothing to peek at. Oh my! I had seen the prayer book in Grandpa’s hands since I was a little child, but it had never occurred to me that it was so difficult to read. And Grandpa didn’t just remember everything, he pronounced all the prayers with emotion, in a singsong manner, swaying back and forth. He uttered those incomprehensible words as if he were saying something very important to God. It was impossible to believe that, at the same time, he didn’t actually understand the meaning of what he was reading. “You need to feel it.” But how did he feel? What did he feel?

The lessons on the couch soon came to an end: Grandpa was always in a hurry to get to work in the morning, so he decided to have our lessons during breakfast to save time. But then things got even worse. He ate noisily and spoke indistinctly. I wanted to eat. None of that contributed to my industriousness or ability to remember the Hebrew words.

As I understand it now, that and the complexity of Hebrew were not the reason. The trouble was my unwillingness to study Hebrew. Perhaps the fact that Grandpa wasn’t an exemplary teacher was partly to blame, but, one way or another, I developed no consuming interest in the ancient language.

I couldn’t give up the lessons. I would tell Grandpa myself, “Let’s do it.” During our lessons, as we were repeating letters, syllables and then words together, some of them managed to stick in my brain. But as soon as Grandpa was about to leave, after instructing me sternly to learn this and that, I became overwhelmed with incredible laziness. The day I’m thinking of wasn’t any different from many other days.

First of all, I had breakfast, of course. It would be wrong to study on an empty stomach. But my desire to learn Hebrew was even less when my stomach was full. I sat down on a chair with the prayer book in my hands by Grandma’s favorite window and, looking closely at the dancing marks, repeated their sound in a whisper. I naturally stumbled on one of the syllables, and at that point my laziness grew to such an extent that… Ah, the day was long, I could do it later. Should I go see Yura? To hell with him. He could have checked on me himself. He must have been studying. Should I go to the yard? But the day was so overcast, gray and cold. Rain was beating against the windowpane. It was so quiet in the yard, so empty…

I was used to Grandpa’s yard being full of sounds year round. Now Grandma Lisa called to someone, then Yura teased Jack, and Jack barked at him, now Robert either complained about something or he and Yura swore at each other… Doors creaked, water hissed and jets sprayed from the hose. Metal roofs creaked from the heat, a rooster “screamed,” sparrows chirped, turtledoves cooed, innumerable insects buzzed, apricots and apples fell off the trees with a thud. It seemed there was nothing in the yard that didn’t produce some kind of sound. All those sounds were interwoven into a melody that existed all by itself. That melody penetrated my being, giving my soul what it needed most – the feeling that everything was fine, that life was beautiful. And the smells of the buds on the trees and shrubs, of grass, flowers, fruit, newly watered vegetable beds, the overheated roof, of falling leaves in autumn, snow in winter – they all mingled cozily with the smells of the houses and the aromas of Grandma’s cooking. And the colors! It’s impossible to enumerate them for many of them don’t even have names, and all the hues and shades of the trees, flowers, fruits and sky, glistening from spring to late autumn.

“Where is all that? Where has it all gone?” I thought, looking through the foggy window covered with drops of rain at my favorite yard. It looked as if it weren’t alive. Why? Because these autumn days were so cold and rainy? No… Hadn’t Yura and I felt nice and happy on similar dreary days? How we had loved to rake fallen leaves together… And now they lay like a motley carpet all over the yard, getting wet, and nobody swept them up. We used to rake them into piles and set fire to them. How wonderfully they had burned when the weather was dry! What heat they emitted! If it drizzled, they gave off smoke. We used to sit by the biggest pile, inhaling the smell of the smoldering leaves, which was unlike anything else. It might have smelled acrid to someone else, but we didn’t think so. Once we even made an Indian pipe, stuffed it with dry leaves and smoked it. We coughed, and smoke almost came out our ears, but we felt really fine.

Yes, the leaves were still here, but the yard was lifeless. “Perhaps I felt that way because Yura was gone,” I thought sadly. Robert had moved out. There was no one for Grandma Lisa to quarrel with, to instruct, to supervise… She was bored and she quieted down. And the yard quieted down too. “Yes, of course, that’s what the matter is,” I thought. But still, this thought, not yet clear, didn’t give me peace of mind. Why did it worry me? I brushed it away like a fly.

I got up and picked up the prayer book Grampa used to teach me to read and set it in its place in the old cupboard.

I had loved that beautiful old cupboard since I was a little child. You opened its doors, and they didn’t creak but rather played a soft tune, their own tune, which was more pleasant and expressive than, say, the creaking of chairs. Besides, the cupboard also had its own very pleasant smell. I thought that was how a very old tree must smell.

Grandma kept Passover dishes in the cupboard. Where the upper part rested on the lower part, between its legs there was a deep niche in which Grandpa’s prayer books, siddurim, were lined up in a row. There were about ten of them.

On the day we started our Hebrew lessons, Grandpa told me to look in the cupboard for the prayer book that contained the Hebrew alphabet and the Russian transcription. I don’t believe that I had ever taken anything out of the niche before that day. And now, as I looked into it, I felt that it was from there that the smell that had tickled my nostrils for many years was coming. Yes, that smell came from the books. Some of Grandpa’s prayer books were ancient, turned yellow over time, swollen from being leafed through. Some of the pages were even cracked – they printed books on thick paper in the old days. The prayer book I got out of the cupboard was published in 1905. I raised it to my nose and inhaled the bitter-sweet, slightly acrid smell of the old book with pleasure. “It’s so old,” I thought, “it was practically printed in the last century.”

At that time, 1905 seemed like ancient times to me.

It may seem strange, but it was exactly during those days that my love for old books arose. It’s strange because I gave up Hebrew after a short time, and I never learned how to read a prayer book. But I liked to hold those books in my hands, to leaf through their yellow pages, to inhale their smell, and to think of how many hands had leafed through them, how many eyes had read them. Those people were long gone, but the books were still here…

That’s when it became a habit with me, and it has remained with me my whole life: as soon as I come across a book, the first thing I do is check when it was published. And that habit gave rise to many other ones. No, not really habits but feelings that I truly treasured.