Полная версия

Полная версияEverything Begins In Childhood

Everything just seemed calm, but if you could only hear how our hearts were pounding. There was something in those touches of hands in the passage, something about what songs were sung, poems created. Still it could never be explained and never would be.

Hearts sank in anticipation. “Who will he choose? What if it isn’t me?” “Will he go with me?” “What if she goes with someone else?”

That was how I thought too, dashing into the passage under the joined hands and making my way to Larisa. I touched her hand. Our fingers gave a start. We got out of the passage, then to the end of the line still holding hands, then we raised them. Those were blissful moments.

We didn’t play the stream in high school; we just looked at each other.

I wasn’t that timid in my dreams. It wasn’t difficult to recall what we supposedly talked about with Larisa as I remembered the previous day. It was even easier to imagine that we were traveling together because books always filled my head with dreams of travel to faraway lands, of adventures. I could spend whole evenings drawing the maps of Thanksgiving Island where Robinson Crusoe wound up. I knew every nook and cranny of that island. Only instead of Robinson, Larisa and I lived in his hut. Sometimes it was a different island where we found ourselves after the wreck of our ship. Larisa became my wife. We made love wherever we could – in the hut, on the beach to the sound of the surf, in a rocky grotto.

Of course, the best of all was to imagine it at night when I was already in bed. And everything seemed so real that I had to wash off traces of that reality in the shower in the morning. And then, when I was at school in the afternoon, I couldn’t make myself look at Larisa: what if she guessed what I had been imagining?

Maybe our daytime relations didn’t advance because of my passionate night reveries. Everything remained the same: my daytime love and passionate night dreams, “A spring named Larisa” and the wife I caressed.

I don’t know whether teenage love can be purely romantic. I think not. We were ordinary teenagers, and the feelings that gripped us during that difficult time of sexual awakening very often incited us to deeds, not only far from romantic, not only crude, but sometimes simply monstrous.

Yes, girls were often presented with candies. Some of us would carry a briefcase for a chosen one, accompanying her home from school. And some of us would toss a dead mouse into a locker room before P.E., only to carry it out heroically by the tail, to the sound of the girls' squealing, making sure to swing the dead thing right in front of their noses.

But it could also be something worse, much worse.

* * *We were walking to biology class, first down the long corridor, then up the steps to the fourth floor. Sergey Belunin was in the middle of our group. It was he who made everyone roar with laughter. Belunin had visited a farm over the weekend, and now he was telling us in detail how they mated horses there. The whole point of his story was that a stallion had been given a stimulant in his fodder before mating.

“You should have seen it…” Sergey said accompanying his words with an expressive gesture.

The walls were about to crumble from the roaring of our laughter.

And Sergey, light-haired and tall, just smiled. It turned out that he had saved a surprise for us, and he took it out of his pocket. It was a small paper package of white pills.

“Here it is. I’ve stolen them. You can check how it works if you don’t believe me. Who wants to check? How about you, Vitya?”

Vitya Smirnov waved his hands and shook his head. The laughter became incredibly loud.

“Hey you, be quiet. Look here. What if we give it to our babes? To Umerova, for example, or Kadushkina…”

That was a great idea! It came from Dima Malatos. Everyone grew silent for a second; then an ecstatic roar broke out.

Thickset and cheerful, Dima was Greek. There were many Greeks in Chirchik. There were three boys in our class – Dima Malatos, Vasya Lumis and another Dima, Hodjidimitriadis. We also had Greek girls. They were slender and good-looking, and the boys were real athletes. I had always felt frail and feeble next to Dima. He moved like a bear. He ambled, but his gait was springy and didn’t look clumsy. He had amazingly thick black hair. His straight bangs came down to his eyebrows, which were also thick and black.

I often wondered why Greek boys were so healthy and handsome, as if chosen. That was how generously nature had endowed their nation. Could it be because of the cruel treatment of newborn babies in ancient Greece? When a feeble baby or a baby with a defect was born, that baby would be thrown over a cliff. We read about it when we studied the history of the ancient world in fifth grade. It was certainly bad and inhumane, but selection happens in nature, natural selection.

I heard – Dora, our neighbor had spoken about it – that the Greeks appeared in our parts in the fifties, after the military junta staged a coup in Greece and the “Regime of the Colonels” dictatorship was established. Democrats and especially communists were persecuted, and many of them emigrated. Some of those Greeks found refuge in Central Asia. “We have a wonderful country,” I thought proudly when I learned about it. “We give refuge to the persecuted. The Koreans also settled here.”

But lately, different thoughts, strange and uneasy, had cropped up. This was the second year that Greeks had begun to leave their homes of many years and return to their homeland. Our Dora, for example, had left. My schoolmates, including Dima, also spoke about it. I wanted very much to ask, why? What made them leave for a capitalist country? It was so good in our country. Besides, they had been born here, they had become Soviet children.

But even more surprising was that the Greeks were allowed to leave. They made preparations for their departure without concealing it, telling everybody about it. And people didn’t become indignant about it; they sympathized with them. But why did people look maliciously at the Jews who wanted to leave? Friends shunned those who wanted to leave. Acquaintances stopped visiting them. Someone might call them traitors, Zionists. My relatives uttered the word “Israel” only in a whisper, and if they planned to leave, they kept it secret. Yura’s grandfather Gavriel had left recently. Only a very small group of people had known about it up until the day of his departure.

I myself thought it was a shame to leave, but Greek boys weren’t at all ashamed of it. Why?

I certainly didn’t ask any questions, I was embarrassed, but it was a pity that such nice, cheerful boys might leave our class.

* * *So, it was Dima Malatos, the nice cheerful boy, who agreed to carry out the “experiment.” It didn’t cross our minds that it was cruel and dangerous.

One of us had filled caramels in his briefcase. They were given to Dima, along with the white pills, and he went to the restroom to replace the filling. Then our gang burst into the classroom. The bell rang, but Margarita Vasilyevna hadn’t yet shown up. There was, as always before a class started, a noisy crush in the classroom, and no one paid attention to our gang. At last, Dima appeared, ambling slowly. He had a small paper bag in his hands, and he was sucking on a caramel. He took his seat at the back of the classroom, not far from Irena Umerova, threw his briefcase on the desk and smiled broadly at Irena.

“Do you want a candy? Help yourself.”

Irena Umerova. There wasn’t a single boy, and not only in our class, who didn’t follow Irena with his eyes when she walked down the corridor. Some gazes were delighted, some simply hungry, undressing her. Irena knew that perfectly well. She was pretty, really pretty, and not vulgar. She had a wonderful figure with all the feminine attributes, and she refused to conceal it. If not for the school rules, Irena would have come to school in a bathing suit. But her dress was very much like a bathing suit – short and hugging her fantastic round breasts. We had already become experts: we scrutinized any pictures with images of naked women – either clipping them from foreign magazines secretly passed around or studying reproductions of paintings by great artists. But even Raphael hadn’t managed to portray breasts like Irena’s. Understandably, Irena had always had admirers, often in abundance. Timirshayev and Shalighin once got into a fight over her. Neither of them was in our class any longer, but Irena didn’t grieve – others turned up.

Irena smiled at jolly Dima, said “thank you” and picked out a couple of caramels. Our second “star,” bespectacled Larisa Kadushkina, was also treated to candies, as well as Natasha Kistanova and someone else.

Margarita Vasilyevna began the lesson with an explanation of the new material. She ran the pointer over a large sheet of paper attached to the blackboard depicting a liver as she spoke about it. I didn’t attempt to hear exactly what she was saying, like all the participants in the experiment. Liver was the last thing on our minds. We were watching our “guinea pigs.”

The first evidence of the effect of the drug manifested itself by the middle of the class. Irena became anxious. She fidgeted in her seat, changed position, rubbed one knee against the other. Finally, she raised her hand:

“Margarita Vasilyevna, may I go out?”

Margarita Vasilyevna shook her head – “Wait a bit, I’m still explaining.” Only a minute passed before Irena rushed out of the classroom.

Natasha Kistanova raised her hand a bit later.

Now, the most difficult thing was to keep from laughing. Dima Malatos couldn’t stand it any long – he leaned heavily on his desk and buried his face in the crook of his arm.

Zulya was the third to raise her hand. Her face was red, and she looked scared.

“Are you trying to disrupt my class?” Margarita Vasilyevna asked in surprise.

The girls hadn’t returned to the classroom by the time class was over.

We later learned that, fortunately, none of them had gotten sick: they just had a minor allergic reaction.

* * *Now, I am trying to understand: am I ashamed to remember that? I am, a bit, but, for some reason, not much. That was the way we were. Nothing could be done about it.

I remember one thing very well: when Dima was giving away caramels, I suddenly panicked – what if Larisa took one? “I won’t allow it,” I thought. “If she does, I’ll take it away from her.”

Chapter 55. “Child in Time” and Children of Our Time

The drums and bass guitar were the first to begin. They slowly sketched out the sad tune of a song, along with the organ. The organ was electric, attaching significance and depth to the tune.

More electric instruments used in rock music had appeared in recent years. Their new timbres and unusual sounds captivated us. And synthesizers! It was amazing what they combined into a common sound stream – voices, laughter, dogs barking, the hum of a flying helicopter. All that was interwoven into a tune and was punctuated by a rhythm – and the music gained new charm.

The tune flew and expanded. Here the voice of a singer became a part of it. What was he pleading for? What was he longing for? What was he complaining about? It really touched our hearts.

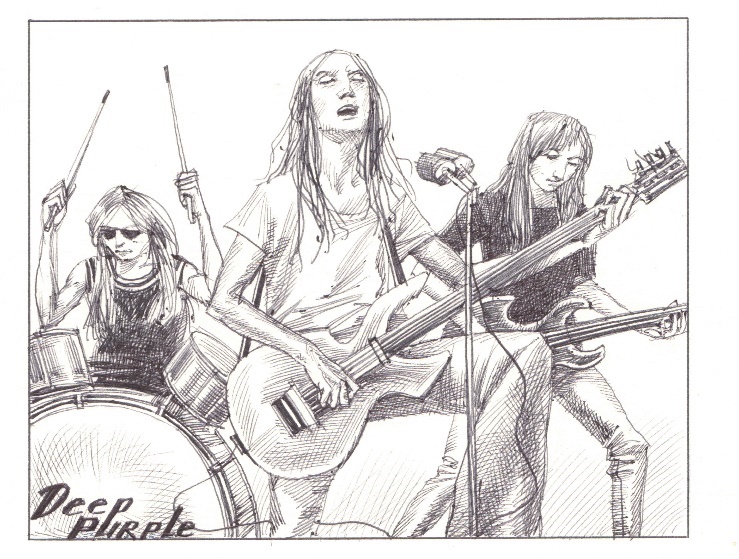

We were listening to the English rock band Deep Purple. We knew the title of the song, but we weren’t sure how to translate it into Russian: was it “Child in Time” or “The Child of Time?” We didn’t understand the meaning of the expression at that time. We had never heard it before, which was why it seemed mysterious, mystical. However, the more mysterious it was, the more interesting.

We were listening to Deep Purple at Andrey Baidibekov’s house, at his birthday party. We were five, not counting Andrey. He had appeared in our class this school year and very soon became everybody’s favorite. He wasn’t tall, rather thickset, with narrow eyes in a round face. I liked him a lot.

When Baidibekov listened to someone or simply looked over something, squinting his eyes, he looked very profound and serious. But he had only to laugh, and the narrow slits turned into wide-open hazel eyes, his eyebrows flew up to touch his black hair, thick, elastic and stiff, and his whole face became wonderfully artless and merry.

I felt very calm and safe next to Andrey. It seemed to me that our personalities had much in common. In a word, we became friends right away.

Andrey had come to Chirchik to live with his older brother, who had gotten a job here. Their parents and other siblings – it was a family with many children – lived not far from Tashkent.

The Baidibekov brothers settled in the building next to ours – that very building the construction of which had attracted us so much – in a cozy studio apartment. That was where we were celebrating Andrey’s fifteenth birthday.

I stood on the small balcony. The fearless construction worker had sat smoking, his legs dangling down somewhere around here above me. That had been about ten years ago.

Ah, how time flew. And now I was looking at the view the construction worker had seen from this balcony. I could see the crowns of trees and part of Yubileynaya beyond them. That was on the right. And on the left, I could see the hills beyond the buildings.

“Yuabov, where are you-u?!”

Sasha Lokshev didn’t actually need to yell: the table was right at the door to the balcony. It was either music or alcohol that had such an effect on Sasha.

“I’m here,” I answered and returned to the table, which was very festive, set by our own hands.

And we had also brought the food: Vitya Yarosh brought salads, I – pilaf made by Mama, Sasha Lokshev provided wine and vodka – yes, yes, we already considered ourselves adults. Lokshev had also provided female company: he had brought along his friend Vera, a tall, shapely girl who quite conformed to our favorite characterization – “a poet’s dream.”

“Dear Andrey!” the light-haired Sasha proposed a toast, raising his glass, “Good luck, bro… To you!”

We clinked glasses and drank. It must have been our fourth drink. Our heads were spinning slightly; the music was playing and playing… Sasha picked Vera up, and they began to whirl, stomping their feet and bending over. The bright flowers on Vera’s dress flashed by. She squealed. Sasha kissed his girlfriend on the lips and, as they continued to dance, swept her away to the kitchen. Well… that could certainly be good. But we felt great without it.

Deep Purple got worked up, increasing in intensity. The guitars, the organ, the drums, the voices – all blended together, becoming an outburst. And here it came, the moment when you didn’t notice anything around you anymore. The whole of you got absorbed in the music… You were in a different world… It was so good there. You felt you also belonged in that world, along with those by whom you were enchanted, with whom you would want to be… whom you would want to be… And then it seemed to happen.

We were not at the table in Andrey Baidibekov’s apartment. We were the rock group Deep Purple. The bright rays from colored floodlights, moving and gleaming, lit us, the stage, the outdoor space where we were performing.

There was a sea of heads in front of us. That sea swayed, made noise, roared, raged like a sea in a storm. Thousands of eyes were fixed on us. We saw them and we didn’t at the same time. We heard the enthusiastic roar and we didn’t. We were working. Each of us had his favorite instrument, his role.

“Sweet child in time.” That’s what Vitya Smirnov, who was also Ian Gillan, was singing. Vitya got into his role as Ian so much that he even resembled him. Just like Ian, he shut his eyes slightly and moved his head. His long hair fell onto his face… Of course, he couldn’t reproduce his voice, but he definitely rendered his manner precisely.

“Toom-m… Toom-toom-toommm…” And that was Andrey. He played the drums, drums and cymbals, twelve of them. He manipulated his spoons no worse than Ian Paice did his drumsticks. He could also create different sounds. He could beat the rhythm so gently that it sounded like a nightingale’s trill. But he could also bang down so hard that it felt like artillery bombardment.

Now, Andrey, along with the bass guitarist Vitya Yarosh, played quietly and slowly. They played background accompaniment, which was very important. Keeping that in mind, they exchanged glances in order to play in coordination.

I listened to them with my eyes half-closed. My turn hadn’t come yet.

But here, the sounds of the percussion were getting louder and more powerful. Andrey was totally enraptured. He got a kick out of it. Andrey shook his head – up and down, up and down. And the spoons in his hands worked to the utmost, slicing the air.

Vitya Yarosh stood, his head thrown back, pressing the strings of the guitar with the fingers of his left hand. His right hand was down at his waist, and he ran the fingers of his right hand over the strings and tapped the guitar: “boom-m, boom-m, boom-m-m.”

And then Lokshev ran out of the kitchen.

So, the organist Jon Lord had heard everything. He had missed just a minute of it. Bending over the table, Sasha ran his fingers over the keys of the organ.

The singer fell silent, only the music sounded, the musicians played to the max, at the fastest tempo, with all their hearts.

And at last, the long-awaited moment had come – the guitar solo was to be played. And I was the one to play it. Richie Blackmore’s guitar was the heart of the rock band. Gentle, leisurely, clear, it usually created a special lyrical mood. But now, the guitar had to be different: it had to be lightning fast, reaching the highest notes, creating tension…

Yes, it was my turn to play. And I struck the strings. My eyes couldn’t follow my fingers, which ran over the strings so rapidly. The guitar… The air appeared to grow dense, I felt the weight of its wooden body. It seemed to me that I was the musician and the guitar at the same time. I shook my head slightly, raised my leg and jumped up and down. My eyes were half-closed. I, like all the others, didn’t need sheet music or conductor.

We felt both the music and each other. We were a unified organism.

That was all… The last chords sounded. The percussion grew silent. We stood, swaying slightly. Only now did we feel how tired we were.

Our hair and shirts were wet. Sweat was streaming down our foreheads and into our eyes. And the crowd of spectators was still making noise, roaring and screaming in front of us.

Some of them jumped, yelling, others whistled, some shook their fists, some tried to get closer to the stage, stepping on shoulders and heads. A forest of swaying hands flew up.

That was fame. And who doesn’t want fame at fifteen?

Well, it takes a lot to achieve fame.

We turned off the tape recorder. Andrey dried his wet face and waved to Yarosh – time to fill the glasses… We had a drink, sat in silence, still filled with the music.

“It would be great to go to a rock concert,” Vitya sighed.

‘Oh, yeah, to a Russian folk choir… or a Soviet pop singer, who was popular in the 50s,” Sasha giggled. “Keep on dreaming.”

We all laughed, but it wasn’t merry laughter.

There were concerts in Chirchik sometimes, but they had nothing to do with rock music. We couldn’t even dream about it. Rock music was considered a “Western plague,”, a “demoralizing influence,” and so on and so forth. They wrote about it in the newspapers, yelled about it on the radio, spoke about it in schools.

No matter how hard numerous mentors tried to turn us away from rock, it had already become a part of our lives. We were children of our time, and the times were the most powerful mentor. Rock captivated us. It became not just another infatuation but something much more important. Deep Purple, Pink Floyd, Led Zeppelin – our favorite groups were often the subject of our conversations. Those who managed to get original records were considered very lucky. But there were only a few of them. Everybody else coaxed disks out of their owners and ran to a sound studio to tape them. That one tape would be recorded over and over.

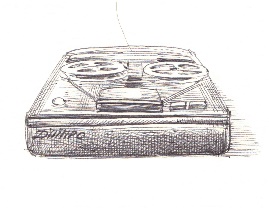

It was one of those tapes that had been recorded from the disk of the concert performance by the rock group Deep Purple that played at Andrey’s apartment today.

“It would be great to get good equipment,” I said, running my fingers over the tape recorder. “By the way, where did you get this one?”

“I borrowed it from an acquaintance,” Lokshev said.

“Has it overheated?”

“Seems it hasn’t…”

Two big reels with tape were turning on the Dnipro tape recorder. The Dnipro was considered portable, but it was terribly heavy and most certainly outdated. However, we were glad we could use it. Needless to say, none of us had his own tape recorder, and at that point we didn’t all even have a record player.

So, what was it about rock that captivated us? Perhaps the secret lay in the fact that it emancipated us. It gave us a feeling of freedom, freedom from irksome and presumptuous teachers, from boring classes, from parents who watched over us obtrusively – in a word, from everybody and everything.

* * *We might ask ourselves – why rock? Why didn’t classical music or concerts of the famous Soviet pop singer Magomayev create the same sensation? Perhaps rock could convey the feelings that gripped a teenager. It gave vent to energy that raged inside you, drew you into its realm, turned you into a participant in an event. It’s not accidental that members of the audience scream at rock groups’ concerts. They all are very young. They badly need to “blow off steam.”

I still like rock. To tell you the truth, it scares me that this “madness” often knows no bounds. Rock turns into something like drugs, except that a person doesn’t need anything else and isn’t interested in anything else. Sometimes I think, at famous rock groups concerts, “Good heavens, is this yelling, screaming crowd listening to performers?” It seems that the music is for them only a signal for some sort of altered state.

Perhaps, I’m wrong – does that happen because I’m already past a certain age? But I know one thing for sure: it didn’t happen to us, my friends and me. We loved music and knew how to listen to it. We could dismiss the imitations and make the right choice – classic rock.

From time to time, I take out albums of our old favorite songs, go through them and listen with pleasure: “July Morning,” “Belladonna,” “Hotel California,” “Let It Be.”

And I remember our “musical repasts.” It seems to me – maybe my words are much too high-sounding – but it seems to me that our improvisation wasn’t just a childish affectation but a creative action. No? You don’t agree with me? Then try, just for half an hour to imitate a rock group, without instruments, reproducing the music with your whole body, every muscle, every cell.

Bulat Okudzhava, a famous bard of the 1960s, sang in his song “The Musician”:

I wasn’t simply curious; I was flying the sky.

No, I wasn’t bored at all, I was hoping to understand

how these hands could possibly make these magic sounds…

* * *Something like that also happened to us.

Chapter 56. The Torture

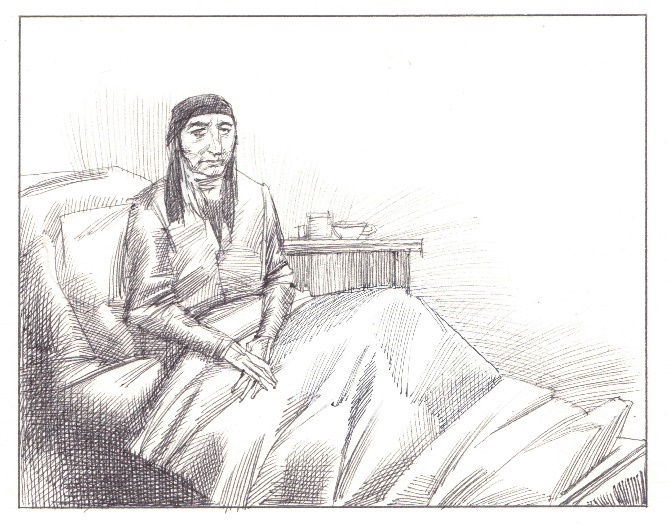

“Remember, in fifty minutes, not before that,” Uncle Avner said sternly as he left the porch, walking after Mama. Mama turned around, nodded to me as if confirming his words, and sighed deeply.

I closed the door behind them and lingered there. Oh, how I didn’t want to return to that room. How scary it was to hear her groans… They weren’t quite groans but slow plaintive entreaties:

“O-oy, I can’t take it anymore. O-oy, Valery, I can’t. Where are you? Untie them.”

It was Grandma Abigai moaning and groaning. Pale and haggard, she was sitting up in her bed. Even though she was leaning against the pillows, her posture was tense, unnatural. That was because Grandma’s legs were bandaged to a board.

Grandma Abigai had had problems with her knees for a long time. I had heard about it so often that I had grown used to Grandma’s illness and her inability to walk properly, as if it were something totally natural. All old people had health problems… Mama, of course, worried, suffered and was eager to go to Tashkent. But I… When I heard about it, I felt sorry for her, but it would immediately leave my mind.