Полная версия:

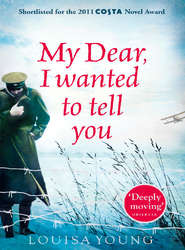

My Dear I Wanted to Tell You

It was hard walking past the end of his parents’ street each day without having time to stop in and say hello, but he had so much to do, working like a demon at his studies, and at his duties, not to let Sir Alfred down. As well he always wanted to see what his mentor had been painting each day, and he couldn’t bear to miss any visitors – men of the world, blasé young students, knights of this and that, Nadine – or interesting outings where he could carry Sir Alfred’s sketching things and hear what he had to say about ancient Egypt or Sebastiano del Piombo or whatever turned up. And he needed time to draw, himself, because it seemed he wasn’t bad, actually . . . not good, but not bad . . .

Patterns and habits grew up, and it all seemed very normal. Time passed, and it was normal. Even for Bethan, the sudden lurches of maternal loss subsided after a year or two. They were lucky. Placing a boy was like marrying off a daughter – the good parents’ first responsibility. And Riley was, it seemed, placed, and happily. The years of Riley’s late childhood were, by any standard, long and nourishing and golden; blessed, not riven, by the double life he was able to lead. The weeks belonged to school and Sir Alfred, and Sundays to his family, when he would eat, and let the little girls climb all over him and use him as a seesaw and make him throw them up in the air. Loads of older brothers and sisters lived away, after all, and came back slightly too big for the little house they’d been born in. It only made them more glamorous.

*

Early one mild spring Saturday morning, seven years after he had first come to Orme Square, Riley, now eighteen, took the long, unwieldy pole that Sir Alfred could no longer manage and unwound the bolts on all the skylights and high windows in the studio. A beautiful soft air slipped in off the park and the squares, limpid, blossomy, dancing with cherry and lilac. Riley was thinking, How would you paint that? Who could paint that clean lightness? Even the horses’ hooves outside on the Bayswater Road sounded lighter. What a day!

Nadine arrived as usual about nine for her drawing lesson, though it wasn’t till ten, and as usual Sir Alfred was still at his coffee, talking to the newspaper. So, as usual, Nadine perched herself on the old workbench up in the studio, wearing her dark blue pinafore, swinging her legs, and watching as Riley laid out brushes, checked supplies, made a list. When he had done he stopped and sketched her instead, light pencil, just a quick thing. He didn’t think it was very good. She was much better than him at getting a likeness. There was a bunch of hyacinths in a glass jar beside her on the dark wood, also blue, the blue of the Madonna’s cloaks in Sir Alfred’s books of Renaissance paintings. He would have liked to paint them, and her. He was fascinated by the variability of colour, by the adjustability of oils. He longed for an excuse to stare at her for hours.

‘I came on my bicycle today,’ she said, testing him out.

‘Can I have a go?’ He had been idly trying to persuade her to come swimming in the Serpentine; she was resisting. She would never come swimming any more. The thought interested him. Maybe he could use the testing of the bicycle to get her into the park, at least.

‘It’s a girl’s bicycle,’ she said.

‘All bicycles are boys’ bicycles,’ he said.

She gave him an evil look. She had long ago persuaded him that the suffragettes were right, but he still liked to torment her. ‘That’s too nearly true to be funny,’ she said. ‘I shall have a motorcycle when I’m older. I’ll go abroad on it, all over the world, drawing and painting everything I see, and paying my way in portraits. No one will stop me.’

‘They wouldn’t dare,’ he said. Why do I keep saying stupid things? Mean things?

‘You mean you wouldn’t dare . . .’ she said, but she said it fondly.

‘I’d dare anything where you’re concerned,’ he said boldly.

‘Oh, you won’t have to. After I’ve been all over the world on my motorcycle I’ll want to come back and be a famous artist and have a lovely house and babies. I’ll bring a kangaroo to be my pet. You can share it.’

‘The kangaroo? Or the house?’ He had a sudden quick vision of an adult life: two easels at opposite ends of a sunny studio.

‘Everything,’ she said. ‘You can even share my motorcycle, so long as you don’t pretend to everyone that it’s yours.’

She said it so easily, he thought she must not have any idea what she was saying. Of course he let the delightfulness of the image dazzle its impossibility into invisibility. Her future, after all, was planned and certain: marriage. His was more . . . open – which allowed him to think impossible thoughts.

Don’t get attached to the girl, Riley. They’re not like us. His mother’s voice.

Change the subject.

They talked about who could paint a spring morning like this one.

‘Samuel Palmer,’ he suggested. She was of the opinion that Palmer was more June, heavier and more lush. He liked to hear her say the word, ‘lush’.

‘Well, Botticelli, of course,’ she said.

‘Perhaps there are springs like that in Italy, but that’s no English spring.’

Then she exclaimed, ‘I know! Van Gogh. Like the almond blossoms.’

They took out the large folder of reproductions that Sir Alfred kept purely, Riley sometimes thought, to sneer at – or perhaps out of fear of such a different way of doing it. They laid out the picture on the long, pale, rough trestle desk under the window, and stood side by side, falling into the picture, the moss and sunlight on the branches, the eternal deep sky behind, the lovely light-catching little blossoms twisted this way and that, the darts of tiny red buds, the one small broken-off branch with its sharp remnant blade pointing up like a thorn in Paradise.

‘I wonder where it is now,’ she said. ‘The actual painting.’ They had seen it in an exhibition at the Grafton Gallery to which Sir Alfred had taken them. The paintings, to Nadine and to Riley, had been perfect, wonderful, naturally beautiful, right, somehow, and they hadn’t understood at all why people were laughing, and expostulating, and leaving.

Riley, who had often taken this picture out and had read the back of the print, said: ‘It’s in Amsterdam.’

‘Let’s go and see it,’ she said.

There, with the pressure of her arm against his, in the morning sun, under the window, smell of oils and turpentine and hyacinth, her voice: ‘Let’s go and see it.’

‘On your motorcycle?’ he said, with a laugh.

‘Yes! Or – in some real way. Let’s do things, Riley. I’m going a little mad, you know. We’ll be grown-ups soon. Let’s DO things. Like when you took me to look at the Snake Lady in Portobello Market, and all those people were singing.’ They’d only been thirteen when they’d done that, and they’d got into terrible trouble. ‘Let’s go to Brighton and paddle and eat shrimps and see the Pavilion! Let’s go to Amsterdam . . .’

‘Let’s run away together to Paris and go to art school,’ he said. ‘Let’s rob a bank and live like kings and go to Rodin’s open weekends at his studio, and wear gypsy robes and eat figs.’

‘Stop it,’ she said. ‘We could do something . . .’

Footsteps on the stairs shut them up. It was one of Sir Alfred’s students, Terence, turning up to work on his big oil of Kensington Palace. Riley felt a strong urge to push him down the stairs. Instead he revelled in a beautiful look of complicity with Nadine, which made his blood run warmer and his heart light and brave.

He glanced at Terence’s painting emerging from its dust-sheet. Why Terence bothered, he hadn’t the slightest idea. It might as well have been painted in 1860. Plus he was doing it from east of the Round Pond, looking west with a sunset behind the palace, so for all he called it Queen Victoria Over the Water, the statue in front of the palace was all wrong because in reality it would be in shade. In fact everything would be in shade, as his light was completely wrong . . . He should be doing it in morning light, but he was too lazy to get up early. Sir Alfred was indulgent with him, Riley thought. But then Sir Alfred is indulgent with me too, so . . .

Oh, go away, Terence.

It was all he wanted now. All he ever wanted. Alone with Nadine. The very words gave him a frisson.

Why should it be impossible? Surely in this big new twentieth century he could find a way to make it possible. After all, his mother would have thought it impossible for him even to know a girl like Nadine . . . Things change. You can make things change. And the Waveneys weren’t like normal upper-class people. They were half French and well-travelled and open-minded. They had noisy parties and played charades and hugged each other, and Mrs Waveney didn’t always get up in the morning. Mr Waveney had told him that champagne glasses were modelled on the Empress Josephine’s breast. There’d been a Russian round there once, and a German with anarchist leanings. Riley had looked that up too.

‘I say, Purefoy,’ said Terence, fumbling around with his canvas. He was a tall, slender young man, with corn-coloured hair, who dropped things. ‘Don’t suppose you’d sit for me a couple of afternoons next week? If Sir Alf can spare you? I’ll pay you . . . There’ll be no . . .’

‘No what?’ said Riley, amused.

Terence glanced at Nadine. ‘Nothing you might not want to do,’ he said delicately. ‘I’ll give you sixpence a session.’

‘How very grand he is,’ giggled Nadine, as Terence left to see if Mrs Briggs would make him a cup of tea.

‘Why does he want to draw me?’ asked Riley.

‘Because you’re handsome,’ Nadine said. She was sitting on the table under the window, looking out, her legs drawn up, pale and studious now with her sketchbook, her black hair wild.

He was surprised by that. ‘Am I?’ he said, and he turned to her, feeling a little bit suddenly furious. ‘You’re beautiful,’ he said, and even as he said it, he couldn’t believe that he had.

She turned to look at him. And she froze, and then he froze, and at the same time the blood was running very hot beneath his skin, and he terribly wanted to kiss her.

She jumped up from the table and stood looking at him.

He was not going to kiss her. He must not kiss her.

He reached out his hand and, very gently, he laid it at the side of her waist, on the curve. This seemed to him less bad than a kiss, and almost as good. His hand settled there: strong, white, paint-stained. She felt its weight, felt how right it felt, felt its possibilities.

The hand relaxed.

They stood there for a moment of unutterable perfection.

Oh, God, but the hand wanted more – to snake round to the back of her waist, to strengthen on the small of her back and pull her in; the other one wanted to dive under the wild black hair to the back of her neck, to spread, to pull her in.

He locked the hand in position, to save the moment, to prolong it, to protect it, to not destroy it: it was a miracle.

He had to take the hand away.

She looked at him. She looked at his hand. She looked up at him again, questioning. Every drop of blood in her was standing to attention. And she laughed, and she ran from the studio, clunking down the stairs, singing a kind of joyful toot ti toot song, a fanfare.

Sir Alfred, coming upstairs, noticed it. He recognised it, and glanced upstairs. Terence? He didn’t think so.

Mrs Briggs, crossing the hall, caught Sir Alfred’s glance for a second, and raised her eyebrows.

*

Someone had shot an archduke. It was in all the papers. Everybody was talking about it.

‘What’s it about?’ Nadine asked Riley.

‘A Serbian shot the Austrian archduke so the Austrians want to bash the Serbians but the Russians have to protect the Serbians so the Germans have to bash France so they won’t help the Russians against the Austrians and once they’ve bashed France we’re next so we have to stop them in Belgium,’ said Riley, who read Sir Alfred’s paper in the evening.

‘Oh,’ she said. ‘What does that mean?’

‘There’s going to be a war, apparently.’

‘Oh,’ she said.

Well, it would be over by the time they were old enough to go to Amsterdam, where he would put his hand on her waist again, and she would laugh and sing but not run away downstairs.

She hadn’t said anything. Neither had he. But when they talked about everything else, and caught eyes when the same thing amused them both and nobody else, or when the orchestra was particularly thrilling, there was a new electric layer to the pleasure they had always taken in these things. Sometimes they looked at each other, and her blood sprang up every time. Sometimes he had to go into another room. He was dying. He didn’t think girls died in the same way. He felt her smile on him, all the time.

*

‘Papa,’ she said easily, happily, walking across the park with him to the Albert Hall. ‘What is it like to be in love?’ She was happier asking him than her mother. Her mother would ask questions, practical ones. It wouldn’t occur to Papa to ask questions about practical things.

‘Oh, it’s marvellous,’ he said. ‘Or terrible. Or both. The Romans saw it as a fit of madness that you wouldn’t wish on anybody. But there’s nothing you can do about it, that’s the main thing.’

She grinned, but he was already thinking again about bar seventy-eight in the slow movement.

*

Sitting for Terence was money for old rope. All that uncertain summer Riley turned up at the tall dark-red house in a row of tall, dark-red houses in South Kensington. He ran up the many flights of stairs to Terence’s studio where, on entering, he marvelled briefly at how messily rich people could live, and he sat. Terence drew him, sketched him, pen pencil watercolour, this angle or that, under the window, by the plant, catching the light, standing sitting lying across that chair.

‘What do you think of the war, then?’ asked Terence, one late August morning. ‘Pretty bad, isn’t it? Everyone’s getting very het up. ’

‘Are you?’ asked Riley.

‘I’m not the type,’ said Terence.

It turned out that ‘not doing anything he might not want to do’ meant not taking his clothes off.

‘I’ll take my clothes off,’ said Riley, mildly. ‘If there’s more money in it.’ Whatever happened, he was going to need money.

There was more money. Riley thought it was funny.

But he quite liked Terence. He observed his manners, copied his nonchalance, stole words off him, and then dropped them again, mostly. The public-school languidity and slang seemed to him unmanly. Riley was looking around for the kind of man he might be going to be, and having trouble finding one. He wasn’t ever going to deny what he was. But he needed to do better. How to reconcile that? He was eighteen now. School was finished, and no one had suggested any possible future activities. How long would he be Sir Alfred’s boy? What could he be, a boy like him? But there was a problem. The first step in every direction was Nadine, and the shadow of Nadine not being permitted overhung . . . everything. Every possible step into every possible future: impossible. Impermissible.

Perhaps if I made lots of money . . . the City? But you need money to start. Art? Not talented enough. And how would you pay for art school?

Crime?

He laughed.

But sitting naked in front of Terence wasn’t going to do it . . .

While Terence drew him, he thought about what he read in the papers: angels appearing on the battlefield, the evil demon Hun, and the boys Over There. He wondered. Boys from Paddington were going, his mother had told him. ‘But don’t you go joining up,’ she said. ‘The army’s just another trick they play on us.’ Her dad, Riley knew, had been killed somewhere in Africa, in the army. ‘You don’t want to go getting involved with abroad,’ Bethan said.

France, to Riley, meant the golden sunflowers Van Gogh had painted in Arles, the bright skies, the lines of trees, the colours of Matisse, the sea, Renoir’s girls in bars, David’s dramatic half-naked heroes, Fragonard’s girls with their petticoats flying, Ingres’ society ladies with their white skin, black hair and melting fingers . . . He thought of Olympia, naked on her chaise-longue, with the little black ribbon round her neck and that look on her face. He thought about Nadine. He thought that, as he was naked, perhaps he had better think about something else.

It was only natural that Terence should stare at Riley’s body, given that he was drawing it. He stared at Riley standing, sitting, lying across the chair. Riley was what they call ‘not too tall but well-knit’, cleanly muscled, and his skin was particularly white like an Ingres lady’s.

‘I don’t suppose . . .’ said Terence, that afternoon. ‘No, of course not.’

‘What?’ said Riley, but Terence wouldn’t say, and suggested they pack up as the light was going, which it wasn’t.

Chapter Three

There was a recruiting party up by Paddington station. On the Sunday, coming back from his mum and dad’s, Riley had seen them marching around in their red coats, the sergeant pointing at men in the crowd, telling them they had to go to France because gallant little Belgium needed them. He’d seen gallant little Belgium on a poster: she was a beautiful woman in a nightie, apparently, being chased by a red-eyed Hun demon in a helmet with a point on it. She became, slightly, in his mind, Nadine’s mother, Jacqueline.

You had to be five foot eight, the sign said. Riley saw a fair number of lads turned away for being too little and skinny. The rest were piling in, and everyone around was cheering them along, and they were grinning sheepishly. Happy and excited. Going to France! Shiny buttons and boots and, Jesus Christ, square meals and a different life!

Once again Riley thanked God, who had so completely blessed him. In his mind he ran through: Sir Alfred, his kindness and generosity; Mum and Dad, their love – except when Dad said art was all very well but a bit nancy, wasn’t it, for a man?; the education he was getting. Though he needed more. Always more. Perhaps in the evenings. There was a Working Men’s Institute . . . history, science, philosophy, maths . . .

And Nadine, that bloody girl. Whom he had to kiss. I will die if I don’t kiss her. But how on earth can I kiss her?

I am a lucky, lucky boy, he thought, and I will do better, I will do whatever it takes, and he swore to himself once again that he would not squander what he had been given.

*

One Saturday Nadine did not turn up.

‘Miss Waveney ill, sir?’ Riley enquired of Sir Alfred, at the ewer in the studio.

Sir Alfred, without looking up, said: ‘Miss Waveney’s well-being is not your concern, Riley.’

Oh!

‘Is it not, sir?’ Riley said carefully, after a moment.

‘No,’ said Sir Alfred.

Riley let that settle a moment. He tried to. It wouldn’t. It grew tumultuous in his belly.

Riley’s fingers moved over the silken tip of the brush he was cleaning, a hollow feeling threading through him.

‘Is she not coming again, sir?’ he said, giving a last opportunity for what was happening not to be true.

‘That’s not your business either, Riley,’ said Sir Alfred.

Oh.

Brush. Fingers. Turpentine.

Damn it, ask outright. He’s implying it.

‘Would she continue to come, sir, if I wasn’t here?’

Sir Alfred almost snapped: ‘Don’t flatter yourself.’ Then he thought for a moment and said precisely: ‘Changes are not made to my household to accommodate the parents of my pupils.’ He looked a warning at Riley: Don’t pursue this. I am not going to discuss it.

Riley had to think about that.

What does he mean? What – what has happened?

Have Mr and Mrs Waveney asked him to get rid of me? Because of Nadine? . . . And has he refused?

He couldn’t read it any other way.

But it’s not fair . . .

‘Miss Waveney is talented, sir,’ he said. ‘More than . . . most.’ He didn’t want to say, ‘more than me’. He knew he couldn’t set himself up against her. Why not? Because she is posh and you are not?

Sir Alfred took his time answering. Eventually he said, ‘Miss Waveney is a girl. She will be happiest and most fulfilled in the bosom of her family, making a good marriage.’

Inside, Riley reeled.

But you knew that all along! a voice inside told him. You’ve always known! You didn’t really hope!

This is not fair. They’ve taken her away. I won’t see her. She won’t learn any more. I won’t see her.

Actually, he had really hoped. And it’s not fair on her! She wants to be an artist, and she could be!

‘I’m going to Terence’s studio this afternoon, sir,’ he said. His voice was small and tight. ‘I shouldn’t be too late.’

He was furious, furious, furious.

*

Rain was gushing down so hard the drainpipes were rattling and overflowing on the back of Terence’s building, and the sky was bruise-coloured at five in the afternoon. Riley bought a newspaper. Over there, men of many nations were fighting the battle of the Marne. The light was bad and Terence couldn’t draw.

He said, ‘Would you like a cup of tea or a beer or something? Wait till it blows over?’

Riley said he’d have a cup of tea, and proceeded to make it on Terence’s little gas ring. The milk jug he kept on the window ledge for the cool (not that it was much warmer inside) had filled up and overflowed already with rainwater. They couldn’t be bothered to go all the way down to get more, so they drank their tea black. Terence brought out some buns, and tried to start up a discussion on proportion and perspective, using the raisins as examples. Riley was not responsive. He was staring round the studio, at the kit, the space, the myriad signs of relaxed independence and creativity. Why should talentless Terence have all this, and Nadine not?

Terence lit a small cigar. ‘What do you think about how the war is going?’ he asked.

‘If we had female succession,’ said Riley, containing his restlessness in a sort of vicious languor, ‘we’d be on the other side. Think about it.’ (He was copying Terence’s quiet confidence. He was mastering it) ‘If Queen Victoria had been succeeded by her eldest daughter, who was . . . ?’

‘Can’t remember,’ said Terence. ‘She had so bally many.’

‘Princess Victoria,’ said Riley, noting that it was not necessary to be well up on the entire royal family to pass, ‘and bearing in mind that Princess Victoria was married to . . . ?’

‘The Pope?’ drawled Terence.

‘Emperor Frederick the Third. She’s Kaiser Bill’s mother. So, Kaiser Bill would be King of England, and we’d all be fighting alongside the Hun.’

‘I say,’ said Terence. ‘Isn’t that treason?’

‘No,’ said Riley. ‘It’s just another truth that people don’t care to look at.’

‘Will you go, do you think?’ Terence asked. ‘I mean, do you think you could? I hope I wouldn’t have to be in it because, to be honest, I’ve been reading the papers, you know, about what went on at Mons and so on, and the Marne now, and of course it will be over by Christmas but, you know, even for a few weeks, I don’t think I could face it – I’m a bit of a coward.’ He looked up, almost shyly. ‘Don’t you think that’s often the case, though, when a man has an artistic temperament? Sir Alf, for example. Of course he’s too old, but could you imagine Sir Alf ever having been the kind of man who could be a soldier? Of course not. Men like him – like us – aren’t the type. But you – you’re different but I do think that you also have an artistic temperament. No, I do. Considering you’ve had no proper training you’re bloody talented. Which some people might be surprised by, you being, as it were, working class . . . but I really don’t see,’ said Terence, aware that he was conveying a great favour, ‘that that’s any barrier to sensitivity. And what is an artistic temperament other than sensitivity? Really?’