Полная версия:

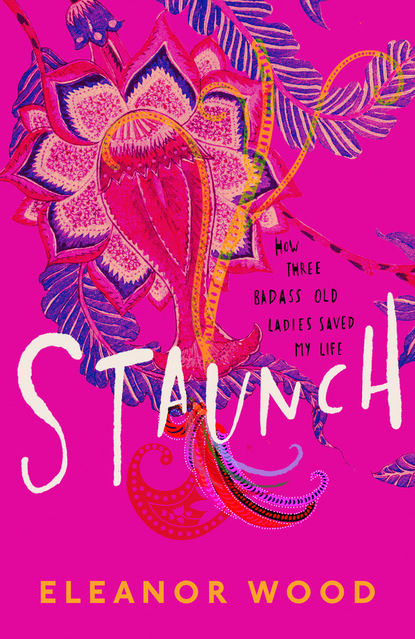

Staunch

At 6 a.m., the universe delivers another unexpected fuck-you. My dad calls me to tell me that my grandpa (‘Parpie’) has died. Despite K asking me not to, I get up and go to work, because what the fuck else am I supposed to do?

April 2003

When I first met K, I was twenty-two. I was low-level bulimic and used to cut myself. I also took quite a lot of drugs and didn’t think any of these things were particularly unusual, because everyone I knew did at least some of them too. I lived in a shared house where we saw a ghost, and a boy we didn’t know once pissed on the sofa. I went out clubbing wearing 1970s evening dresses and I spent every Sunday so hungover I wanted to kill myself.

You don’t need me to go into detail about these years, as you can read similar stories in numerous ‘my lost twenties’ memoirs. You know the drill. However, I will say that my lost years were much worse than any of these, guaranteed. Those books always depress me because the writers’ rock-bottom moments always sounds exactly like a normal Tuesday night for me in the early Noughties.

Anyway, amid all the sad shagging, cocaine and throwing up – when I was twenty-two, my cool older friend Lauren asked me to be in a band. I couldn’t play anything but I looked like I should be in a band, which was apparently good enough. She said her boyfriend Richie could teach me to play bass. Easy.

One Saturday afternoon, we drove to an obscure music shop in High Wycombe, where Richie knew someone who could ‘get us a good deal’ on a bass guitar. That turned out to be K, who looked like the lovechild of Keith Moon and Kurt Cobain in a brown cardigan – he had a mop of black hair, vast green eyes, incredible cheekbones and a slight air of oddness about him that I instantly liked. We got chatting about music and he told me about his band. He sold me a Fender Squier jazz bass, sunburst finish, and I gave him my number.

I chose him in the same way that I had chosen most of my boyfriends up to this point: because he looked cool and was in a band. Thus far, this strategy had not worked out particularly well. I had been dumped a lot by boys who just wanted to ‘focus on their music’, or ‘not be tied down’. I’d had a lot of casual on-and-off things with guys who had thought I was ‘really cool’, while I had been secretly hoping they might fall in love with me and maybe want to marry me. Spoiler alert: they never, ever did. I had never met a boyfriend’s parents or been on a romantic minibreak.

Amazingly, with K, things turned out differently. He called me the next day and asked me if I wanted to go out on a proper date. He took me for a picnic by the river. It turned out that he had been to art college and wanted to illustrate children’s books. He loved Sherlock Holmes and French films and obscure Japanese cartoons I had never heard of. He wasn’t quite as cool as I thought; he was much, much nicer.

He was twenty-seven and he lived in a house by himself. He cooked me pasta and didn’t like drugs. He was slightly disapproving of my friends. I gradually stopped going out so much. I gave up smoking. He made me realize that some of the things I thought were normal were not.

We went on holiday to Devon together and the following year we moved to Brighton. He was the first boyfriend I had ever loved who loved me. He told me he didn’t ever want to get married and I said that was fine. At last, I had something that was real. I could let go of the misguided dream of wanting to marry cool unattainable boys. This was a great compromise. We could forget convention and have a life together that suited us.

We had interesting people round for dinner, and London friends coming to visit all the time. A graffiti artist friend once slept on our sofa for a year. I helped K write lyrics for his band, and he painted a portrait of me in a hotel room in Paris that my mum still has on the wall in her house. I sat at the kitchen table every night in our top-floor Brighton flat, and for the first time I wrote a whole novel.

We went on holidays with my parents. K played music and did a lot of painting and set up a pop-up art gallery – way before these things were known as ‘pop-ups’ – back when having a friend with an empty shop in the centre of Brighton you could use was a normal occurrence.

When Amy Winehouse was at her skinniest and most drug-addled, and for some reason in those days we all thought it was OK to gawp, Stepdad once said to me, ‘Imagine, if you hadn’t met K, that would be you. Only without the talent.’ How we all laughed.

Then ten years later – on that freezing cold Monday in January – the world I thought I knew fell apart and K had to watch me regress before his eyes.

Turns out, it’s acceptable(ish) to be a total fuck-up when you’re twenty-two. At thirty-two, it’s quite embarrassing. Especially when it’s about something as prosaic as a parental divorce. I’d already been through one once, at the age of eleven, and handled it with a lot more grace as a child than I managed to do as an adult. The acute humiliation of this knowledge did not help.

I didn’t know that stilted phone conversation on the floor of my rental flat would be the last conversation we would ever have. Stepdad never spoke to any of us again. He very quickly began to communicate solely through solicitors’ letters. That was when I wrote him an email saying I didn’t want to speak to him again, not that he’d tried particularly hard. When he told me that he loved me and it would be OK, I had no idea I would never hear his voice ever again. I might have tried to say more if I’d known that.

The only way I could get through this was by telling myself he had been kidnapped and someone – possibly Liam Neeson or Jason Statham – was holding a gun to his head and making him do these things against his will.

It’s hard to explain how much I loved Stepdad and how much it fucked me up to lose him. There is something profoundly unsettling about having the rug ripped out from under your feet just as you think you’re living like a real adult and you’ve got everything under control for the first time in your life. I was so proud of myself for how far I’d come from that sad, bulimic, chain-smoking, falling-drunk-off-the-table twenty-two-year-old. Turns out she’d been waiting in the wings the whole time, through all those grown-up minibreaks on the Eurostar and trips to Ikea and all the other things I wrongly thought made me a functional adult.

But mostly, I was just unbearably sad because I loved him so much. My heart was broken in a way that it could never have been by a mere boyfriend. It was the worst break-up imaginable. It taught me that I’d been wrong during those years of painstakingly building up my self-esteem. You can’t trust anyone. People will leave you and they will disappear. Love is not unconditional. You will not be enough. Ever. The person who I thought loved me the most, literally, disappeared.

I got very thin. I started smoking again. I got a huge tattoo and told myself it would stop me from cutting myself, a habit so old it was almost forgotten, but somehow crept back in, under the American Apparel thigh-high socks I started insisting on wearing to bed every night. Quite embarrassing in someone over thirty, really. I lived in fear of K or anybody else finding out. I hid razorblades in strange places. I took two scalding hot baths a day with the doors locked.

I cried constantly. Walking down the street, at work, in bed every night. I didn’t want to be touched because I would fall to pieces. I didn’t want anyone to be kind to me.

I became obsessed with fake tan, a product I had only ever sneered at previously. My skin turned darker and darker, as it collected in my clavicles and between my fingers like nicotine stains. I think I just wanted to be in a different skin.

I stopped sleeping altogether. I was so manic, I kept having what I thought were brilliant ideas, which made no sense. I started writing a ‘brilliant’ new novel, and then when I read it back, it barely even contained real words.

Stranger and stranger superstitions started to take up more and more of my day. I once nearly choked in the house by myself, as I had taken to walking around with a piece of rose quartz in my mouth at all times. Just carrying it with me wasn’t enough.

I started seeing cats everywhere I went, convinced it was ‘a sign’. I started a spreadsheet of every cat I saw, with columns entitled ‘location/colour/character/what they were trying to tell me’. The spreadsheet went so far as to include such entries as ‘Thought I saw a cat under a seat on the train. Followed it. There was no cat’.

A couple of months passed and things did not get better. To the outside world, it didn’t look so bad. I managed to go to work and even to see friends occasionally, but I was just trying to get through the days. Nobody realized quite how bad it was, but I had a force field around me that made other people nervous.

My sister and my nan seemed to get over the shock relatively quickly, but my mum and I did not. My mum kept telling me she was ‘fine’ but was very evidently not fine. I did the same thing back. Every time my phone rang, I braced myself for the news that my mother had committed suicide. I could not see a way that she or I would get out of this alive.

This was perhaps more understandable for my mum than for me. But I just couldn’t get over it. Everything was ruined. Life felt not only futile but fucking impossible. I just couldn’t seem to function like a normal human being. I could not stop crying. But I had K, which seemed to make people think I must be fine. He would look after me, just like he always had.

We started sleeping further apart. We stopped talking. Neither of us was capable of it. K tried to call Stepdad to tell him he thought I was going to kill myself. Stepdad didn’t answer and never called him back.

I went to the doctor and received a letter saying I would be put on a waiting list for psychiatric assessment. A few weeks later I went for the assessment and received another letter saying I would be treated as priority and then nothing happened.

When it became apparent that Stepdad was not going to come back or start behaving like a decent human any time soon, my mum and I went to Hatton Garden to sell her jewellery, then went and spent some of our pirate spoils on a decadent lunch. The guy in the dodgy pawn shop liked us, gave us an extra £50 note from the wedge in his breast pocket, to buy a bottle of champagne on him. If nothing else, we always do our best to make bad times glamorous.

I am not as pragmatic as my mother, even though I could do with the money. My prize possession was a Swiss Army watch that Stepdad gave me, that used to be his. I used to wear it every day, with inordinate pride. Either selling it or throwing it away seemed wrong, somehow. For weeks I kept it in my desk drawer at work, as I didn’t want it in the house.

One morning, after drinking a lot of coffee, I had a flash of inspiration. I pissed on it and posted it to him in a Jiffy bag (to his work address, I still don’t know where he lives) that developed a film of condensation on the inside before I’d even sealed it up. I guess it was the combination of fury, betrayal and shame that made this seem like a perfectly rational course of action. I told people about this calmly, like it was quite a normal thing to do.

Just over six months after Stepdad left, in July, we were supposed to be going on holiday. It had been booked in advance as a family occasion, to celebrate Stepdad’s birthday and my mum’s and his wedding anniversary. It was non-refundable, so we decided to go anyway. It was a very strange week.

My mum would say she was ‘going for a walk’ (aka disappearing down the beach to cry like her heart was broken, which was logical because it was), and everyone else would politely pretend not to notice, while I followed her even though she didn’t want me to. So she and I ended up going for long walks every day, holding hands, in near silence. I couldn’t tell her things like ‘it’s going to be OK’ because that would be a lie, so mostly I just said ‘yeah, I know, me too’. I’m not sure it helped.

My mum and I drank a litre of cheap white wine with our lunch each day and then kept going. K couldn’t deal with it and took to bed for two days, refusing to talk to any of us. My poor sister and her boyfriend were left to try to jolly things up. I guess I shouldn’t blame K – it was stressful for everyone – but I couldn’t help thinking this wasn’t exactly helpful of him.

K and I had already nearly broken up, only a year earlier. Another terrible crisis point – my stepmum Sue had died, suddenly, at the age of fifty-one. Like Stepdad, she had been in my life since I was eleven and had a huge hand in bringing me up. She was the most full-of-life woman I can picture, and she left behind two sons – both much younger than me – whom she adored fiercely. She shouldn’t have died, that’s all I can still think about it.

At Sue’s funeral, I said ‘I want to have a baby’, the first time I had ever really had this thought, let alone spoken it out loud. It did not go away.

K did not react to this as I’d hoped. He simply refused to discuss it. This was not what we had agreed; as he saw it, I was reneging on our deal, which was to be non-conformist and not care about such things. I was letting the side down. He was furious with me. I was so sad and so shocked, I agreed to shut up and hope it would go away.

I can see what I was trying to do, although neither of us could at the time. I’d had a tricky, unsettled childhood but then things had calmed down – four parents, new stepbrothers on my dad’s side, the classic Dad’s-every-other-weekend routine. My life had hinged on that stability for so long that I thought I could count on it. Now I had lost so much of that, no wonder I was desperate for change, to make a brand new life for us that looked different, instead of hanging around in the ruins.

After we came back from our disastrous holiday, more months went by and I began to resemble a normal human again. I became less frail. I stopped dyeing myself orange. I slept better at night and sometimes I could go a day without crying. After a while, it looked to the naked eye like the crisis had passed. K seemed mostly relieved that we’d got through it without him having to talk about it.

So, we’d made it through. Life was a bit worse and we were a bit different, but we seemed to have come out the other side together. Sort of.

Things began to look brighter when I started pouring my energy into writing. This was how I would save myself, I decided. Once I got going, the words flooded out of me with an unstoppable intensity.

I wrote a whole novel in six weeks straight, barely sleeping, not wanting to do anything else. Running away from my own life. I wrote it mostly in bed, just to stay warm – the new house had turned into a disaster.

It was freezing cold, damp and full of woodlice, and it turned out that all the floors were rotten. Everything was falling apart around us.

So, while my life was quietly in ruins, I escaped from it all by writing a sweet romantic comedy for teenagers. And – after years of trying, with various small degrees of success – somehow it ended up being the best thing I had ever written. Suddenly life got exciting again. My agent texted me while I was at work to tell me a big publisher wanted to buy the book I had written.

I immediately rang K and my mum to tell them the news. Even as I was saying it, it didn’t feel real. My mum cried with joy for me, and K took me out for cocktails that night to celebrate.

It was exactly then that all of the stress started coming out in weird physical ways. The next morning (now that I supposedly had everything I had ever wanted in my whole life) I woke up with such intense pins and needles down my right-hand side, I could barely use that side of my body. I had to call a cab to take me to work, as I couldn’t manage the twenty-minute walk. I had recently started a new job for a small healthcare publisher, so I struggled through the day trying to make sure nobody noticed. This was supposed to be the best time of my life! Yes, I was so excited! No, I couldn’t believe it either!

I began to have multiple ocular migraines every day, so severe and constant that I stopped driving, out of pure fear. I haven’t driven since and now I’ve forgotten how. More weird symptoms seemed to develop every day. I started throwing up for no reason, having to spend hours hiding in the loo at work because I was incapable of functioning like a normal human in public. Just like when I used to be bulimic, how retro!

I took to spending my evenings lying in a darkened room, unable to move. I became convinced I was probably dying. I was sent for blood tests and MRIs, and nobody could find anything wrong with me. I concluded that I was definitely dying.

A kind neurologist poked me with needles, and told me to come off the Pill immediately. I was put on it when I was seventeen because I had a burst ovarian cyst, and the Pill reduces the risk of recurrence. I don’t think anybody ever asked me if I suffered from migraines, which I always have. The neurologist was appalled that I was on the Pill at all – let alone that I had solidly been on it for fifteen years. She said my stroke risk, what with the migraines and the smoking – oh, and the family history of strokes – was probably through the roof.

I came off the Pill and immediately felt better. When I told K this, he gave me a funny look I had never seen before and asked me if I didn’t think this was ‘a bit too convenient’. I was so shocked, I didn’t know what he meant at first. Then it turned into a horrible argument.

‘It’s not exactly a surprise.’ He shrugged. ‘We’ve been together over ten years. This is what happens to everyone in the end, isn’t it? Girls pretend they’re cool and they want the same things as you, then next thing you know they’ve trapped you into getting married and having offspring and you have to pretend to be happy about it or everyone thinks it’s you who’s the bastard.’

I asked him if he really felt like we were on opposing sides now, and he said he wasn’t sure. That was the beginning of the end.

We limped on, sadly and undramatically, for a few months. We went on holiday to Hydra, a tiny island where Leonard Cohen used to live and wrote many of his most famous songs – and was therefore my dream destination. I sat on our lovely roof terrace, drinking wine, while K slept a lot. I went for a lot of long walks by myself. We were polite to each other. We both did our best and it wasn’t quite good enough.

Then – almost inevitably, something had to happen – I met a man through work: a funny and handsome journalist. While I had a boyfriend at home who was barely speaking to me, I started saying I was going out with ‘colleagues’ and instead going to grown-up jazz nights with The Journalist, where we would drink red wine and talk about how our partners ‘didn’t understand us’.

I convinced myself it was OK, because we hadn’t actually slept together. But I’m not that naive – I know hanging around in bars and bitching about how useless your boyfriend is … well, it’s not cool. In fact, it is not only uncool, but incredibly dangerous.

The ending finally happened on a perfectly normal weeknight. K and I went round to our neighbours’ house for dinner. They had recently had twins; we all drank wine and ate takeaway fish and chips while the babies slept – one of them on me, while I happily ate my dinner one-handed. If I were allowed to be honest, I would admit this is actually what I would like my own life to look like. As far as I was concerned, it was a lovely evening.

We got home and closed the front door. I was still taking off my coat when I realized that K was just standing there and staring at me.

‘This isn’t going to work,’ he said. ‘That’s what you want, isn’t it? All of that. I would rather fucking hang myself. We’re going to have to break up.’

I burst into tears and said yes, I agreed. He burst into tears and said he didn’t really mean it. It was too late. It was the end.

Well, except it wasn’t. Because we were grown-ups who co-owned a house and a lot of shared furniture. We still had to go on a trip to New York for my sister’s thirtieth birthday, which was like slow torture. Then we had to live in the house together for four months while we argued over what to do with it. Eventually I borrowed money to buy him out.

My family – what remained of it – were devastated. Our friends had to awkwardly pick sides. It was like getting divorced without the legitimacy of having been married. We had built a whole life together, but saying ‘my boyfriend and I are breaking up’ sounded so teenage and inconsequential.

When K and I broke up, I felt desperate for more. More forward motion in life. More passion. More excitement. Something finally happening, not just hanging around waiting for everyone to die or disappear in the end.

I spend the next five years of my life wondering how the fuck I ended up with so much less.

December 2014

While K is finally moving out, I can’t bear to be around for it. So I escape to New York with my mum.

My mum and I are soulmates, very close and scarily similar. If you look at old pictures of us at the same ages, sometimes it’s hard to tell which of us it is. It freaks us both out. Now I’m an adult, we are more like naughty sisters who drink wine and have kitchen discos together.

She travels to New York a lot for work and has a lot of friends in the city. We decide this would be the ideal place for a change of scene, and spend money that neither of us can afford on the trip. We get so drunk and overexcited on the flight out that a stewardess has to ask us to be quiet. We are also asked whether there has been a death in the family when we both weep loudly while watching Beaches.

Unfortunately, just as we arrive, so does a major snowstorm. It’s a freakish cold snap even for the freezing New York winter. There are weather warnings in place and people are advised not to go outdoors.

Of course, my mum and I decide to ignore this advice. We are on holiday, after all! We get wrapped up and go out for a walk in Central Park. It’s so cold, the ice rink is closed. There is not another human to be seen. It’s apocalyptic.

It’s so foggy we have to hold hands to keep together, and before long of course we realize that we are horribly lost. It’s funny at first, but then we realize we can’t feel our faces and become convinced that this is how we are going to die. When the snow thaws, they will find us and, worst of all, they will say how stupid we were to have ignored all those weather warnings.

When we eventually find our way out of the park, there are no cabs because everyone is indoors, so we have to walk sixteen blocks back to our hotel. When we arrive back there, the concierge brings us brandy and blankets.

After that, we decide not to go outdoors again. We do not leave the hotel for the rest of our holiday, not once. It’s strangely relaxing. We order room service. We sit up in our twin beds like Bert and Ernie, and watch TV. We take it in turns to have long hot baths. I go up to the hotel gym and run for hours on the treadmill, looking out of the panoramic windows at nothing but falling snow. We go down to the bar for cocktails and then go straight back up to bed. We soon feel happily institutionalized, like we have always been there and might never leave.

The thing we enjoy the most, and do more than once, is to both get into my bed and watch Grey Gardens on my laptop.

My mum and I have long been obsessive fans of the film Grey Gardens, but on this trip, our love for it reaches new heights. Watching it together here feels very fitting. It’s a strange 1970s documentary about an aristocratic but eccentric and broke mother and daughter, ‘Big Edie’ and ‘Little Edie’, who live together in their dilapidated mansion, Grey Gardens, with a lot of cats and a few raccoons.