Полная версия

Полная версияLord Loveland Discovers America

But worst had not yet come to worst, and as Val's spirits rose with a mingling of good food and bright hopes, he decided against Coolidge as a refuge for the present. In spite of all, he would stick to his guns and not forgather further with the Mauretania people until he had seen what Harborough's letters produced. He could get on for a day or two, and meanwhile there were things to do.

When he had been cheered by luncheon, and soothed by cigarettes, he sent for a motor taxi-cab. The afternoon was still young, and so full of sparkle and gayety that life seemed worth living after all; therefore Lord Loveland had begun to value himself almost as highly as ever, by the time his smart little automobile pulled up in front of the bank.

It was a stately bank, well worthy of its London connection; and he handed in his visiting card and letter of credit, with the air of one entitled to receive unlimited sums. The cashier, however, having looked at him, the card, and the letter, did not appear to be impressed. Instead of replying in words to Loveland's demand for twenty pounds, he walked away with the letter of credit in his hand, and vanished behind a swing door. Loveland thought that he had probably gone to fetch the manager, who would perhaps desire to see in person a titled client of some importance. But after a short delay the cashier returned alone, and having strolled back to his place behind the grating, there stood silent for a moment.

"I'm rather in a hurry," said Loveland. "I suppose there'll be no red tape about my getting twenty pounds? I want it this afternoon."

The cashier smiled a dry smile, and his voice sounded dry as he answered. "I don't know about the red tape, but I'm sorry to tell you we have no instructions from London to pay."

"What?" cried Val, reddening with annoyance. Several people writing cheques or waiting for money at the counter, looked up and continued to look. "You have no instructions?"

"No instructions to pay," repeated the cashier, putting on the last word an emphasis which sounded offensive to Loveland's ears, though he hastily assured himself that it could not possibly have any such meaning.

"This is very inconvenient," said Val, to whom Bridge and tips on shipboard had left exactly seventeen shillings, three pence halfpenny.

"I'm sorry for that," remarked the cashier, still more formally, more unsympathetically, and – one might almost have said – more disrespectfully, than before.

Loveland, though inclined to storm, reflected a moment. He had intended to sail on the Baltic, which was due to leave English shores only yesterday, and might not arrive at New York for seven or eight days. He had not given anyone notice – not even his mother – that he had changed his intention, and very likely the London papers had paragraphed him as a passenger on the Baltic's next trip. Nevertheless, he could not quite understand how that fact excused his London bank's delay in instructing their New York correspondents. They had had plenty of time to arrange his affairs before his sudden departure in the Mauretania, and by not doing so they were likely to make him a great deal of unnecessary trouble.

Again he thought of Cadwallader Hunter. In this instance, too, the man might have been useful.

"Well, I don't see why I should be made to suffer because the London and Southern Bank puts off till tomorrow what it ought to have done a week ago," said Loveland, beginning to be arrogant, though looking boyish, with his flushed face, and his white scar glimmering on its background of clear, ruddy-brown. "I must have some money, you know."

The cashier did not reply to this challenge, and his eyes expressed no interested consideration of the matter.

"You had better see your manager and explain the circumstances," pursued Val.

"It would be useless. We could not pay without instructions."

"I daresay I might manage with ten pounds till you could get an answer, if you choose to be so ridiculously over-cautious," Loveland insisted, loftily. "But in that case you must cable at once."

"You will no doubt be willing to pay for the message in advance?" suggested the cashier.

"Certainly not," said Val, no longer trying to keep his temper under control. "You've seen my card. Isn't that enough for you?"

"Business is business," quoted the bank employé, still unruffled, still blind to Lord Loveland's importance, cold to his necessities.

"And decency's decency," stormed Val, careless now who looked or listened, and in a mood to wreck all American institutions.

"Yes, it's as well never to forget that," the cashier hinted, significantly. "Sorry we cannot accommodate you at present."

"I'm hanged if you ever get the chance again," retorted Val, snatching his letter of credit from the counter. "I shall myself send a cable to the London and Southern which will make you repent your pig-headedness." And with this ultimatum he strode to the door, as if on the way to sign a death-warrant.

"By his looks, that will be an expensive cable, and make the wire mighty hot," Val heard a man chuckle as he passed, and there was a spatter of laughter, which (for his eyes) painted the opposite sky-scrapers bright scarlet.

"Beastly America! Beastly Americans!" he muttered. "I suppose this is their way of resenting the existence of aristocracy."

Lord Loveland had a good deal to learn yet about America – and also about that important member of the aristocracy, himself.

As he returned to his motor cab, which had been "taxing" away violently since he left it, he wondered if he would have enough money to pay for it. But, what if he hadn't? He could tip the chauffeur, and the hotel would do the rest. Also the hotel would put down the cash for a dozen cablegrams. Oh, the sting of these pin-pricks would last no longer than the poison of mosquito-bites! Once Jim Harborough's friends began to rally round him, and vie among each other for his society, as the Mauretanians had done, New York would be his to play with. Patience, then, and shuffle the cards. As he had heard someone say on shipboard, "Faint heart never won a game of poker."

It was thus he smoothed away the sulky frown which suited neither his face, nor the gentle Indian-summer sunshine. Then, trying to forget the first snub man had ever dared to deal him, he flashed here and there in his motor cab, making a house to house distribution of Jim's envelopes and his own visiting cards, according to home custom when armed with letters of introduction.

The sky flamed with sunset banners – Spanish colours – long before he had finished his round and was ready to return to the Waldorf. There, his idea of a suitable present to the chauffeur left him with the American equivalent of eight or nine shillings in his pocket. But, as he had expected, the hotel paid for his afternoon's motoring. So cheerfully did it pay that he sent off an unnecessarily long and extremely frank cablegram to his London bankers which they ought to receive on opening their doors next morning. He thought that it would rather wake them up, and that in consequence of their response to New York – certain to flash immediately along the wires – he would receive an apology from the rude wretch who had insulted him that afternoon. But nothing would induce him to forget or forgive. He had informed the London bankers that his business must be diverted into another channel, which they were invited to suggest.

When Loveland found himself alone again in his luxurious suite of rooms, with the November night coming on, and no amusement on hand (unless he chose to stare down from his high windows at the blaze of astonishing jewels which festooned the immense blue dusk with light and colour) he half wished once more that he had not been so cautious in the matter of accepting invitations. After all, it wouldn't have compromised his future, if he had gone to dine with the Coolidges, or Spanish-eyed, flirtatious Mrs. Milton and her gentle little daughter Fanny. A dinner with them – or even with the dullest people who had invited him – would have been preferable to an undiluted dose of his own society on this first night in a strange land. However, it was too late to reconsider now with dignity (though he was childishly confident that any of his American acquaintances would have been entranced, had he suddenly changed his mind) and the next best thing to dining with friends would be to watch the coming and going of gay New York in the Waldorf-Astoria restaurant.

He dressed and went down about eight, therefore, looking forward to the novelty of the unknown.

CHAPTER ELEVEN

The Discovery of Lord Loveland by America

It was a brilliant scene into the midst of which Loveland plunged.

Society begins to dine earlier in New York than in London; therefore at eight o'clock dinner was in full swing. There was scarcely an empty table; and many of the women being in hats and semi-evening dress, the red and gold restaurant suggested to the newcomer a living picture of Paris.

He had had the forethought to telephone down and order a table to be kept for him, and informing an interrogative waiter that he was Lord Loveland he learned that his place would be found at the far end of the room.

It looked a very far end indeed, gazing across an intervening sea of flowerlike hats, charming faces, and jewelled necks that glimmered white under film of lace and tulle; but Loveland was not shy. Among all the men who protected the charming faces, his sweeping, faintly supercilious glance did not show him one whose physical advantages he need envy. He rather enjoyed his progress, winding on and on along narrow paths between rose-burdened tables, with lovely eyes lifting to his as he passed by. He wondered if any pair of those eyes was destined to look down his own table at Loveland Castle some day. Well, they should be beautiful eyes to deserve the honour! the thought slipped vaguely through his head, and then his own eyes brightened with the light of recognition.

There, at a large table decorated with white and purple violets, sat Elinor Coolidge, her father, Mrs. Milton and Fanny, and two men whom Loveland had never seen before. Standing, and bending slightly down to talk in a confidential tone with one of these men, was Major Cadwallader Hunter.

His back was turned towards Loveland, who recognised him instantly, however, by the set of his high, military shoulders, and the bald spot on his head which Lesley Dearmer had likened to the shape of Italy on the map. He seemed to listen with deep interest to what one of the seated men was saying, and then to chime in eagerly with some addition of his own. Everyone at the table was absorbed in the conversation between these two, and as Loveland came nearer, he saw that the expression of all the faces, including those of the three ladies, was so grave as to appear out of keeping with the liveliness of the scene. Suddenly, however, Loveland caught Fanny Milton's eye. She started, and blushed scarlet. The slight, involuntary movement she made drew Miss Coolidge's attention: and Elinor, seeing the direction in which Fanny's eyes were turned, sent a glance that way.

Loveland, within bowing distance now, met the glance, and returned it, smiling. He was annoyed that Cadwallader Hunter should be with the party, even though evidently not of it. Yet, after all, he said to himself, perhaps it was as well. He did not mean to apologise to Cadwallader Hunter, for he thought his own rudeness more or less justified by the liberty the other had taken; but he had already made up his mind that, the next time he met the man, he would act as if nothing disagreeable had happened. As to Cadwallader Hunter's readiness to snatch at the olive branch, Loveland had not the slightest doubt of it. He thought he had only to hold out a hand for the Major to kiss it, grovelling.

Elinor Coolidge did not blush at the sight of Lord Loveland as Fanny Milton did, but her beautiful face changed curiously. Its cameo-clear lines hardened, her lips were pressed together, and her large eyes narrowed, gleaming like topazes between their dark lashes, as the lights from the shaded candles on the table lighted sparks in their yellow-brown depths.

The thought flashed into Loveland's head that the quick change in her face meant jealousy of Fanny Milton. He had noticed more than once on shipboard that she had seemed jealous of Fanny, and now that deep blush of the younger girl's at sight of him, had probably vexed her. He could not attribute the hardening of the beautiful features to any other cause, and as of the two it was wise to prefer Elinor and her millions to Fanny and her thousands, he let his first look, his first words, be for the Coolidges, father and daughter.

"How d'you do?" he asked, pausing at the table.

Instead of answering, or putting out her hand to him as he expected, Elinor almost convulsively grasped the sticks of a delicate little fan which lay beside her plate. She shot a topaz glance at one of the two new men, then let her eyes under raised brows seek and hold her father's.

Lord Loveland was at once surprised and puzzled by this extraordinary reception. "Can Cadwallader Hunter have told them all some lie to set them against me?" he asked himself. But it was no more than a passing thought. It was incredible that Miss Coolidge should believe anything against him.

At the sound of Loveland's voice, Cadwallader Hunter straightened up in haste and turned round, looking suddenly stiff and wicked as a frozen snake.

He stared into Loveland's eyes, his own like grey glass; and an unpromising smile depressed the corners of his thin lips.

"Oh, that's it, is it?" thought Val, with the carelessness of a man used to dominating situations. "He's afraid I'm not going to speak to him, and he daren't speak first for fear of being snubbed again. Well" – and Val felt pleasantly magnanimous – "I'll give him a lead. How are you?" he asked, with the patronising tone his voice unconsciously took when he spoke to this man.

Then he could hardly believe his eyes which told him that Cadwallader Hunter had turned a contemptuous shoulder upon him, darting disgust in a venomous glance.

"This is the – person we were speaking of," he said to the dark, clean-shaven man towards whom he had been bending (he seemed always to be bending towards someone) when Loveland came up. "Shall we have him turned out?"

Mr. Coolidge half rose in his seat, losing his characteristic stolidity. "No, no," he returned, in a low, decided voice, "there must be no scene here, for the ladies' sake. Keep quiet, everybody."

"You're right, Coolidge," returned the dark, smooth-faced man.

Then the latter fixed his eyes on Loveland with a stare under a frown; and the other new man stared also; but the three women looked away, trying in vain to think of something easy and natural to say to each other. A slight, nervous twitching which occasionally disturbed the tranquillity of Mrs. Milton's camellia-white face became visible; Elinor Coolidge was pale and motionless; and Fanny's eyes swam in a lake of tears which she struggled to keep from over-flowing.

Again it struck Loveland that he was living in a dream; the gorgeous room; the crowd of well-dressed men and beautiful women; the hurrying waiters; the lights; the fragrance of flowers and food, and scented laces; the chatter of laughing voices subdued by distance; and more unreal than all, the table surrounded by the faces that he knew, faces he had expected to find smiling in friendship, now frozen into something like horror – horror at him, Lord Loveland, whom everybody had always wanted and admired.

It could not be true. It was not happening really. Things like this did not happen.

He stood for a moment, stupidly, like a boy in the school-room who has been bidden to stand up and be stared at as a punishment for some misdemeanour. He was almost inclined to laugh at the insolence of Cadwallader Hunter, as a lion might laugh at a fox terrier worrying his foot. It was on his lips to say, "What a tempest in a tea-pot! Surely you're not going to believe any idiotic tale that tuft-hunting ass may have trumped up about me?"

But he bit back the words. If they chose to champion Cadwallader Hunter in his silly grievance against a Marquis of Loveland, why, let them. They would be sorry afterwards – when it was too late. To sneer Cadwallader Hunter down as he deserved would be to make a disagreeable scene, and the business was squalid enough already. He would have thought better of the Coolidges, if not of the Miltons, mother and daughter; but he said to himself that none of them were worth even the shrug of the shoulders he gave, as with his head held gallantly high, he passed on towards his own table.

The little dramatic episode, if observed by any audience, had been played too subtly to be understood by those not concerned. Those seated nearest might have seen that, when a handsome young man stopped to speak to some members of a party at a table, another man who did not belong to that party, had looked at him scornfully and whispered venomously; that then one or two others had spoken hurriedly, and that the handsome young man had stalked away apparently in disgust.

But several of the neighbours knew the party at the table by sight, and Cadwallader Hunter also. These consulted together, and wondered who was the tall young man who looked like an Englishman. The women commented flatteringly upon his face or his figure, but the men were of the opinion that, judging by the way Cadwallader Hunter ("Pepys Junior" they called him) had eyed the chap he must be the rankest kind of an outsider.

There were two chairs at Loveland's table-placed in case he might choose to bring a guest – and he deliberately selected the one which put him with his back to the Coolidge party. But he had forgotten that Major Cadwallader Hunter was not one of that party, and might wander at will to any part of the dining-room. Presently he did begin to wander, stopping to talk with another group of people, then with another, and so on, always on his way somewhere else.

Loveland, utterly sick now of his late friend, did not bestow a glance upon the thin, high-shouldered figure as it paused and flitted, flitted and paused, like a fastidious bee in a flower-garden. A polite waiter had slipped a menu into the hand of Loveland, who regarded the decorated square of cardboard as if it were a fetish to preserve him from evil. But if he had deigned to let his eye follow Cadwallader Hunter, he would have seen that each group of people glanced with furtive curiosity at him; stared, whispered, stared again, and afterwards signalled each other from table to table, across flowery spaces, lifting eyebrows and exchanging signs of a secret intelligence.

Cadwallader Hunter prided himself on knowing all the people who were worth knowing, wherever he went, and those he did not know at the start, he generally contrived to know at the finish. He had at least twenty or thirty acquaintances in the restaurant of the Waldorf-Astoria tonight; and having heard from one of these a startling piece of news (which would have been less welcome yesterday) he dropped bits of the rich honey-pollen here and there, as he made his way towards the door. He had dined early, because he had been minded to show himself, rather late, at the first performance of a new comedy by the brilliant young playwright, Sidney Cremer; but now he found himself appearing on the stage and acting almost a leading part in a drama a hundred times more exciting than he could see at any theatre. He went straight from the restaurant to the long row of desks in the hotel office for a heart to heart talk with the clerk he had interviewed in the morning. Then, having made the impression and obtained the assurance he desired, he searched for other acquaintances in that vast, decorative corridor of marble, facetiously known as "Peacock Alley." He knew several of the best Peacocks there (for there were all kinds, from North, South, West and East, to many of whom Cadwallader Hunter would not have deigned to bow, even if they were smeared with gold and dipped in diamonds), and he talked to those of his choice more loudly than he had talked in the dining-room. Acquaintances whom he button-holed, and strangers who could catch the drift of what he was saying – listened with interest, and then sat or stood about with the air of expecting that some exciting event might happen.

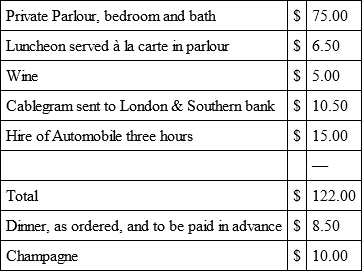

Meanwhile Loveland ordered his dinner, though not quite as carefully as he would had it not been for the disagreeable little incident which he tried to forget as if it were but one more in the series of pin-pricks. As he had no money – at present – to pay for it, he thought he might as well drown his vexations in champagne, and asked for a bottle of the brand he liked best, without even enquiring the New York conception of its price.

As the waiter would have gone off with the order, Val called him back, on a sudden thought. "Do you know the names of the people at the table where I stopped?"

"Yes, sir," replied the man. "They are very well known here. We often have them dining and lunching. Mr. Coolidge is a millionaire. He and his daughter are just back from Europe, and Mrs. and Miss Milton, too."

"Yes, yes," said Loveland, impatiently. "I know all that. But the others?"

"Oh, the smooth shaved gentleman with the black hair and prominent eyes, he's Mr. Milton, Mrs. Milton's husband, rather a gay sort of gentleman, sir. The story is, he and Mrs. Milton don't get along very pleasantly. There'll be plenty here tonight will be interested, seeing them together just after her coming home with the young lady. And the other gentleman, sir, the good-looking, young one with the dark moustache, that's one of our greatest New York swells, Mr. Henry van Cotter. He – "

"Thank you. That will do," broke in Loveland, suddenly annoyed by the servant's knowing loquacity. The name of Henry van Cotter had, in such a connection, stirred a dim sense of discomfort within him. This van Cotter was one of Harborough's friends. Val had left Jim's letter, and a visiting card this afternoon at a huge palace of an "apartment house," where Mr. van Cotter had a flat.

The waiter, thus checked, trotted away with the order for dinner, and was so long in returning that Val (who did not see him stopped and harangued by a grave-faced superior) wondered and grew impatient. Other people were served, while he still sat idle. He was not hungry, for an angry tingling in his veins had burnt up his appetite for dinner, as his keenness for luncheon had been destroyed, but he resented being kept waiting, as if he were a person of no importance.

At last he saw his waiter coming back, and was about to ask irritably whether the man thought it was tomorrow's breakfast he'd ordered, when a sealed envelope of the hotel paper was laid on the table in place of the expected oysters.

The servant discreetly retired out of sight behind his lordship's chair, like a little boy who has lit a squib and awaits the explosion; and Loveland tore open the envelope which, very oddly, he thought, was not addressed.

He had a vague expectation that the contents would prove to be a note from Cadwallader Hunter, and the reality came upon him as a complete surprise.

"Sir," he read, in neat typing, "the management of the hotel presents its compliments, and informs you that the suite you are occupying will be required from this evening, also that they regret they have no other room to place at your disposal. They therefore enclose your account up to date, and request the favour of immediate payment. Should you wish for dinner and wine, they would be obliged if you would kindly pay in advance. The bill for same (as ordered by you) is enclosed separately from the other account."

Now, surely, he would at last wake up from this wild nightmare, and find himself at home in England, or still on the ship. Nothing had seemed real since he landed, and could not be real. Foxham could not have stolen his clothes; the New York bank could not have refused to give him money; Cadwallader Hunter could not have induced Henry van Cotter, the Coolidges and Miltons to cut him; and, above all, the hotel he honoured with his patronage could not have flung in his face this monstrous insult.

Nevertheless, there was the bill staring up at him, as he stared down at it.

Lord Loveland, hardly knowing what he said or did in the persistent nightmare from which he could not wake, called the waiter to him, from ambush behind his chair.