Полная версия

Полная версияMemoirs of General W. T. Sherman, Volume II., Part 4

3. If Mr. Cohen remains in Savannah as a denizen, his property, real and personal, will not be disturbed unless its temporary use be necessary for the military authorities of the city. The title to property will not be disturbed in any event, until adjudicated by the courts of the United States.

4. If Mr. Cohen leaves Savannah under my Special Order No. 148, it is a public acknowledgment that he "adheres to the enemies of the United States," and all his property becomes forfeited to the United States. But, as a matter of favor, he will be allowed to carry with him clothing and furniture for the use of himself, his family, and servants, and will be trans ported within the enemy's lines, but not by way of Port Royal.

These rules will apply to all parties, and from them no exception will be made.

I have the honor to be, general, your obedient servant,

W. T. SHERMAN, Major-General.

This letter was in answer to specific inquiries; it is clear, and covers all the points, and, should I leave before my orders are executed, I will endeavor to impress upon my successor, General Foster, their wisdom and propriety.

I hope the course I have taken in these matters will meet your approbation, and that the President will not refund to parties claiming cotton or other property, without the strongest evidence of loyalty and friendship on the part of the claimant, or unless some other positive end is to be gained.

I am, with great respect, your obedient servant,

W. T. SHERMAN, Major-General commanding.

CHAPTER XXIII

CAMPAIGN OF THE CAROLINASFEBRUARY AND MARCH, 1865On the 1st day of February, as before explained, the army designed for the active campaign from Savannah northward was composed of two wings, commanded respectively by Major-Generals Howard and Slocum, and was substantially the same that had marched from Atlanta to Savannah. The same general orders were in force, and this campaign may properly be classed as a continuance of the former.

The right wing, less Corse's division, Fifteenth Corps, was grouped at or near Pocotaligo, South Carolina, with its wagons filled with food, ammunition, and forage, all ready to start, and only waiting for the left wing, which was detained by the flood in the Savannah River. It was composed as follows:

Fifteenth Corps, Major-General JOHN A. LOGAN.

First Division, Brigadier-General Charles R. Woods; Second Division, Major-General W. B. Hazen; Third Division, Brigadier-General John E. Smith; Fourth Division, Brigadier-General John M. Corse. Artillery brigade, eighteen guns, Lieutenant-Colonel W. H. Ross, First Michigan Artillery.

Seventeenth. Corps, Major-General FRANK P. BLAIR, JR.

First Division, Major-General Joseph A. Mower; Second Division, Brigadier-General M. F. Force; Fourth Division, Brigadier-General Giles A. Smith. Artillery brigade, fourteen guns, Major A. C. Waterhouse, First Illinois Artillery.

The left wing, with Corse's division and Kilpatrick's cavalry, was at and near Sister's Ferry, forty miles above the city of Savannah, engaged in crossing the river, then much swollen. It was composed as follows:

Fourteenth Corps, Major-General JEFF. C. DAVIS.

First Division, Brigadier-General W. P. Carlin; Second Division, Brigadier-General John D. Morgan; Third Division, Brigadier-General A. Baird. Artillery brigade, sixteen guns, Major Charles Houghtaling, First Illinois Artillery.

Twentieth Corps, Brigadier-General A. S. WILLIAMS.

First Division, Brigadier-General N. I. Jackson; Second Division, Brigadier-General J. W. Geary; Third Division, Brigadier-General W. T. Ward. Artillery brigade, Sixteen gnus, Major J. A. Reynolds, First New York Artillery.

Cavalry Division, Brigadier-General JUDSON KILPATRICK.

First Brigade, Colonel T. J. Jordan, Ninth Pennsylvania Cavalry; Second Brigade, Colonel S. D. Atkins, Ninety-second Illinois Vol.; Third Brigade, Colonel George E. Spencer, First Alabama Cavalry. One battery of four guns.

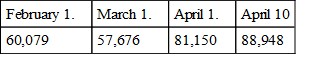

The actual strength of the army, as given in the following official tabular statements, was at the time sixty thousand and seventy-nine men, and sixty-eight guns. The trains were made up of about twenty-five hundred wagons, with six mules to each wagon, and about six hundred ambulances, with two horses each. The contents of the wagons embraced an ample supply of ammunition for a great battle; forage for about seven days, and provisions for twenty days, mostly of bread, sugar, coffee, and salt, depending largely for fresh meat on beeves driven on the hoof and such cattle, hogs, and poultry, as we expected to gather along our line of march.

RECAPITULATION—CAMPAIGN OF THE CAROLINAS

The enemy occupied the cities of Charleston and Augusta, with garrisons capable of making a respectable if not successful defense, but utterly unable to meet our veteran columns in the open field. To resist or delay our progress north, General Wheeler had his division of cavalry (reduced to the size of a brigade by his hard and persistent fighting ever since the beginning of the Atlanta campaign), and General Wade Hampton had been dispatched from the Army of Virginia to his native State of South Carolina, with a great flourish of trumpets, and extraordinary powers to raise men, money, and horses, with which "to stay the progress of the invader," and "to punish us for our insolent attempt to invade the glorious State of South Carolina!" He was supposed at the time to have, at and near Columbia, two small divisions of cavalry commanded by himself and General Butler.

Of course, I had a species of contempt for these scattered and inconsiderable forces, knew that they could hardly delay us an hour; and the only serious question that occurred to me was, would General Lee sit down in Richmond (besieged by General Grant), and permit us, almost unopposed, to pass through the States of South and North Carolina, cutting off and consuming the very supplies on which he depended to feed his army in Virginia, or would he make an effort to escape from General Grant, and endeavor to catch us inland somewhere between Columbia and Raleigh? I knew full well at the time that the broken fragments of Hood's army (which had escaped from Tennessee) were being hurried rapidly across Georgia, by Augusta, to make junction in my front; estimating them at the maximum twenty-five thousand men, and Hardee's, Wheeler's, and Hampton's forces at fifteen thousand, made forty thousand; which, if handled with spirit and energy, would constitute a formidable force, and might make the passage of such rivers as the Santee and Cape Fear a difficult undertaking. Therefore, I took all possible precautions, and arranged with Admiral Dahlgren and General Foster to watch our progress inland by all the means possible, and to provide for us points of security along the coast; as, at Bull's Bay, Georgetown, and the mouth of Cape Fear River. Still, it was extremely desirable in one march to reach Goldsboro' in the State of North Carolina (distant four hundred and twenty-five miles), a point of great convenience for ulterior operations, by reason of the two railroads which meet there, coming from the seacoast at Wilmington and Newbern. Before leaving Savannah I had sent to Newbern Colonel W. W. Wright, of the Engineers, with orders to look to these railroads, to collect rolling-stock, and to have the roads repaired out as far as possible in six weeks–the time estimated as necessary for us to march that distance.

The question of supplies remained still the one of vital importance, and I reasoned that we might safely rely on the country for a considerable quantity of forage and provisions, and that, if the worst came to the worst, we could live several months on the mules and horses of our trains. Nevertheless, time was equally material, and the moment I heard that General Slocum had finished his pontoon-bridge at Sister's Ferry, and that Kilpatrick's cavalry was over the river, I gave the general orders to march, and instructed all the columns to aim for the South Carolina Railroad to the west of Branchville, about Blackville and Midway.

The right wing moved up the Salkiehatchie, the Seventeenth Corps on the right, with orders on reaching Rivers's Bridge to cross over, and the Fifteenth Corps by Hickory Hill to Beaufort's Bridge. Kilpatrick was instructed to march by way of Barnwell; Corse's division and the Twentieth Corps to take such roads as would bring them into communication with the Fifteenth Corps about Beaufort's Bridge. All these columns started promptly on the 1st of February. We encountered Wheeler's cavalry, which had obstructed the road by felling trees, but our men picked these up and threw them aside, so that this obstruction hardly delayed us an hour. In person I accompanied the Fifteenth Corps (General Logan) by McPhersonville and Hickory Hill, and kept couriers going to and fro to General Slocum with instructions to hurry as much as possible, so as to make a junction of the whole army on the South Carolina Railroad about Blackville.

I spent the night of February 1st at Hickory Hill Post-Office, and that of the 2d at Duck Branch Post-Office, thirty-one miles out from Pocotaligo. On the 3d the Seventeenth Corps was opposite Rivers's Bridge, and the Fifteenth approached Beaufort's Bridge. The Salkiehatchie was still over its banks, and presented a most formidable obstacle. The enemy appeared in some force on the opposite bank, had cut away all the bridges which spanned the many deep channels of the swollen river, and the only available passage seemed to be along the narrow causeways which constituted the common roads. At Rivers's Bridge Generals Mower and Giles A. Smith led, their heads of column through this swamp, the water up to their shoulders, crossed over to the pine-land, turned upon the rebel brigade which defended the passage, and routed it in utter disorder. It was in this attack that General Wager Swayne lost his leg, and he had to be conveyed back to Pocotaligo. Still, the loss of life was very small, in proportion to the advantages gained, for the enemy at once abandoned the whole line of the Salkiehatchie, and the Fifteenth Corps passed over at Beaufort's Bridge, without opposition.

On the 5th of February I was at Beaufort's Bridge, by which time General A. S. Williams had got up with five brigades' of the Twentieth Corps; I also heard of General Kilpatrick's being abreast of us, at Barnwell, and then gave orders for the march straight for the railroad at Midway. I still remained with the Fifteenth Corps, which, on the 6th of February, was five miles from Bamberg. As a matter of course, I expected severe resistance at this railroad, for its loss would sever all the communications of the enemy in Charleston with those in Augusta.

Early on the 7th, in the midst of a rain-storm, we reached the railroad; almost unopposed, striking it at several points. General Howard told me a good story concerning this, which will bear repeating: He was with the Seventeenth Corps, marching straight for Midway, and when about five miles distant he began to deploy the leading division, so as to be ready for battle. Sitting on his horse by the road-side, while the deployment was making, he saw a man coming down the road, riding as hard as he could, and as he approached he recognized him as one of his own "foragers," mounted on a white horse, with a rope bridle and a blanket for saddle. As he came near he called out, "Hurry up, general; we have got the railroad!" So, while we, the generals, were proceeding deliberately to prepare for a serious battle, a parcel of our foragers, in search of plunder, had got ahead and actually captured the South Carolina Railroad, a line of vital importance to the rebel Government.

As soon as we struck the railroad, details of men were set to work to tear up the rails, to burn the ties and twist the bars. This was a most important railroad, and I proposed to destroy it completely for fifty miles, partly to prevent a possibility of its restoration and partly to utilize the time necessary for General Slocum to get up.

The country thereabouts was very poor, but the inhabitants mostly remained at home. Indeed, they knew not where to go. The enemy's cavalry had retreated before us, but his infantry was reported in some strength at Branchville, on the farther side of the Edisto; yet on the appearance of a mere squad of our men they burned their own bridges the very thing I wanted, for we had no use for them, and they had.

We all remained strung along this railroad till the 9th of February–the Seventeenth Corps on the right, then the Fifteenth, Twentieth, and cavalry, at Blackville. General Slocum reached Blackville that day, with Geary's division of the Twentieth Corps, and reported the Fourteenth Corps (General Jeff. C. Davis's) to be following by way of Barnwell. On the 10th I rode up to Blackville, where I conferred with Generals Slocum and Kilpatrick, became satisfied that the whole army would be ready within a day, and accordingly made orders for the next movement north to Columbia, the right wing to strike Orangeburg en route. Kilpatrick was ordered to demonstrate strongly toward Aiken, to keep up the delusion that we might turn to Augusta; but he was notified that Columbia was the next objective, and that he should cover the left flank against Wheeler, who hung around it. I wanted to reach Columbia before any part of Hood's army could possibly get there. Some of them were reported as having reached Augusta, under the command of General Dick Taylor.

Having sufficiently damaged the railroad, and effected the junction of the entire army, the general march was resumed on the 11th, each corps crossing the South Edisto by separate bridges, with orders to pause on the road leading from Orangeberg to Augusta, till it was certain that the Seventeenth Corps had got possession of Orangeburg. This place was simply important as its occupation would sever the communications between Charleston and Columbia. All the heads of column reached this road, known as the Edgefield road, during the 12th, and the Seventeenth Corps turned to the right, against Orangeburg. When I reached the head of column opposite Orangeburg, I found Giles A. Smith's division halted, with a battery unlimbered, exchanging shots with a party on the opposite side of the Edisto. He reported that the bridge was gone, and that the river was deep and impassable. I then directed General Blair to send a strong division below the town, some four or five miles, to effect a crossing there. He laid his pontoon-bridge, but the bottom on the other side was overflowed, and the men had to wade through it, in places as deep as their waists. I was with this division at the time, on foot, trying to pick my way across the overflowed bottom; but, as soon as the head of column reached the sand-hills, I knew that the enemy would not long remain in Orangeburg, and accordingly returned to my horse, on the west bank, and rode rapidly up to where I had left Giles A. Smith. I found him in possession of the broken bridge, abreast of the town, which he was repairing, and I was among the first to cross over and enter the town. By and before the time either Force's or Giles A. Smith's skirmishers entered the place, several stores were on fire, and I am sure that some of the towns-people told me that a Jew merchant had set fire to his own cotton and store, and from this the fire had spread. This, however, was soon put out, and the Seventeenth Corps (General Blair) occupied the place during that night. I remember to have visited a large hospital, on the hill near the railroad depot, which was occupied by the orphan children who had been removed from the asylum in Charleston. We gave them protection, and, I think, some provisions. The railroad and depot were destroyed by order, and no doubt a good deal of cotton was burned, for we all regarded cotton as hostile property, a thing to be destroyed. General Blair was ordered to break up this railroad, forward to the point where it crossed the Santee, and then to turn for Columbia. On the morning of the 13th I again joined the Fifteenth Corps, which crossed the North Edisto by Snilling's Bridge, and moved straight for Columbia, around the head of Caw-Caw Swamp. Orders were sent to all the columns to turn for Columbia, where it was supposed the enemy had concentrated all the men they could from Charleston, Augusta, and even from Virginia. That night I was with the Fifteenth Corps, twenty-one miles from Columbia, where my aide, Colonel Audenried, picked up a rebel officer on the road, who, supposing him to be of the same service with himself, answered all his questions frankly, and revealed the truth that there was nothing in Columbia except Hampton's cavalry. The fact was, that General Hardee, in Charleston, took it for granted that we were after Charleston; the rebel troops in Augusta supposed they were "our objective;" so they abandoned poor Columbia to the care of Hampton's cavalry, which was confused by the rumors that poured in on it, so that both Beauregard and Wade Hampton, who were in Columbia, seem to have lost their heads.

On the 14th the head of the Fifteenth Corps, Charles R. Woods's division, approached the Little Congaree, a broad, deep stream, tributary to the Main Congaree; six or eight miles below Columbia. On the opposite side of this stream was a newly-constructed fort, and on our side–a wide extent of old cotton-fields, which, had been overflowed, and was covered with a deep slime. General Woods had deployed his leading brigade, which was skirmishing forward, but he reported that the bridge was gone, and that a considerable force of the enemy was on the other side. I directed General Howard or Logan to send a brigade by a circuit to the left, to see if this stream could not be crossed higher up, but at the same time knew that General Slocum's route world bring him to Colombia behind this stream, and that his approach would uncover it. Therefore, there was no need of exposing much life. The brigade, however, found means to cross the Little Congaree, and thus uncovered the passage by the main road, so that General Woods's skirmishers at once passed over, and a party was set to work to repair the bridge, which occupied less than an hour, when I passed over with my whole staff. I found the new fort unfinished and unoccupied, but from its parapet could see over some old fields bounded to the north and west by hills skirted with timber. There was a plantation to our left, about half a mile, and on the edge of the timber was drawn up a force of rebel cavalry of about a regiment, which advanced, and charged upon some, of our foragers, who were plundering the plantation; my aide, Colonel Audenried, who had ridden forward, came back somewhat hurt and bruised, for, observing this charge of cavalry, he had turned for us, and his horse fell with him in attempting to leap a ditch. General Woods's skirmish-line met this charge of cavalry, and drove it back into the woods and beyond. We remained on that ground during the night of the 15th, and I camped on the nearest dry ground behind the Little Congaree, where on the next morning were made the written' orders for the government of the troops while occupying Columbia. These are dated February 16, 1865, in these words:

General Howard will cross the Saluda and Broad Rivers as near their mouths as possible, occupy Columbia, destroy the public buildings, railroad property, manufacturing and machine shops; but will spare libraries, asylums, and private dwellings. He will then move to Winnsboro', destroying en route utterly that section of the railroad. He will also cause all bridges, trestles, water-tanks, and depots on the railroad back to the Wateree to be burned, switches broken, and such other destruction as he can find time to accomplish consistent with proper celerity.

These instructions were embraced in General Order No. 26, which prescribed the routes of march for the several columns as far as Fayetteville, North Carolina, and is conclusive that I then regarded Columbia as simply one point on our general route of march, and not as an important conquest.

During the 16th of February the Fifteenth Corps reached the point opposite Columbia, and pushed on for the Saluda Factory three miles above, crossed that stream, and the head of column reached Broad River just in time to find its bridge in flames, Butler's cavalry having just passed over into Columbia. The head of Slocum's column also reached the point opposite Columbia the same morning, but the bulk of his army was back at Lexington. I reached this place early in the morning of the 16th, met General Slocum there; and explained to him the purport of General Order No. 26, which contemplated the passage of his army across Broad River at Alston, fifteen miles above Columbia. Riding down to the river-bank, I saw the wreck of the large bridge which had been burned by the enemy, with its many stone piers still standing, but the superstructure gone. Across the Congaree River lay the city of Columbia, in plain, easy view. I could see the unfinished State-House, a handsome granite structure, and the ruins of the railroad depot, which were still smouldering. Occasionally a few citizens or cavalry could be seen running across the streets, and quite a number of negroes were seemingly busy in carrying off bags of grain or meal, which were piled up near the burned depot.

Captain De Gres had a section of his twenty-pound Parrott guns unlimbered, firing into the town. I asked him what he was firing for; he said he could see some rebel cavalry occasionally at the intersections of the streets, and he had an idea that there was a large force of infantry concealed on the opposite bank, lying low, in case we should attempt to cross over directly into the town. I instructed him not to fire any more into the town, but consented to his bursting a few shells near the depot, to scare away the negroes who were appropriating the bags of corn and meal which we wanted, also to fire three shots at the unoccupied State-House. I stood by and saw these fired, and then all firing ceased. Although this matter of firing into Columbia has been the subject of much abuse and investigation, I have yet to hear of any single person having been killed in Columbia by our cannon. On the other hand, the night before, when Woods's division was in camp in the open fields at Little Congaree, it was shelled all night by a rebel battery from the other aide of the river. This provoked me much at the time, for it was wanton mischief, as Generals Beauregard and Hampton must have been convinced that they could not prevent our entrance into Columbia. I have always contended that I would have been justified in retaliating for this unnecessary act of war, but did not, though I always characterized it as it deserved.

The night of the 16th I camped near an old prison bivouac opposite Columbia, known to our prisoners of war as "Camp Sorghum," where remained the mud-hovels and holes in the ground which our prisoners had made to shelter themselves from the winter's cold and the summer's heat. The Fifteenth Corps was then ahead, reaching to Broad River, about four miles above Columbia; the Seventeenth Corps was behind, on the river-bank opposite Columbia; and the left wing and cavalry had turned north toward Alston.

The next morning, viz., February 17th, I rode to the head of General Howard's column, and found that during the night he had ferried Stone's brigade of Woods's division of the Fifteenth Corps across by rafts made of the pontoons, and that brigade was then deployed on the opposite bank to cover the construction of a pontoon-bridge nearly finished.

I sat with General Howard on a log, watching the men lay this bridge; and about 9 or 10 A.M. a messenger came from Colonel Stone on the other aide, saying that the Mayor of Columbia had come out of the city to surrender the place, and asking for orders. I simply remarked to General Howard that he had his orders, to let Colonel Stone go on into the city, and that we would follow as soon as the bridge was ready. By this same messenger I received a note in pencil from the Lady Superioress of a convent or school in Columbia, in which she claimed to have been a teacher in a convent in Brown County, Ohio, at the time my daughter Minnie was a pupil there, and therefore asking special protection. My recollection is, that I gave the note to my brother-in-law, Colonel Ewing, then inspector-general on my staff, with instructions to see this lady, and assure her that we contemplated no destruction of any private property in Columbia at all.