Полная версия

Полная версияRambles and Recollections of an Indian Official

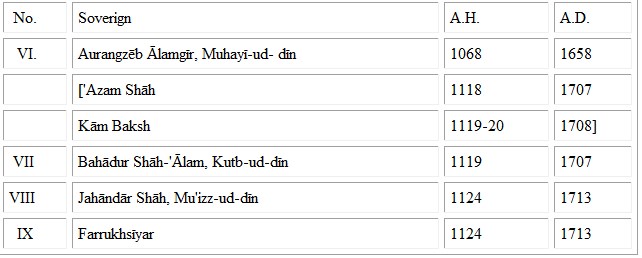

The above note is not altogether accurate. 'Azam, the third son of Aurangzēb, was killed in battle near Agra, in June 1707. During the interval between Aurangzēb's death and his own, he had struck coins. Mu'azzam, the second, and eldest then surviving son, after the defeat of his rival, ascended the throne under the title of Shāh Ālam Bahādur Shāh, and is generally known as Bahādur Shāh. He was then sixty-four years of age, his father having been eighty-seven years old when he died. The events following the death of Bahādur Shāh are narrated as follows by Mr. Lane-Poole; 'The Deccan was the weakest point in the empire from the beginning of the reign. Hardly had Bahādur appointed his youngest brother, Kām Baksh ('Wish-fulfiller'), viceroy of Bījāpur and Haidarābād, when that infatuated prince rebelled and committed such atrocities that the Emperor was compelled to attack him. Zū-l-Fikār engaged and defeated the rebel king (who was striking coins in full assumption of sovereignty) near Haidarābād, and Kām Baksh died of his wounds (1708, A.H. 1120).

'In the midst of this confusion, and surrounded by portents of coming disruption, Bahādur died, 1712 (1124). He left four sons, who immediately entered with the zest of their race upon the struggle for the crown. The eldest, 'Azīm-ash-Shān ("Strong of Heart"), first assumed the sceptre, but Zū-l- Fikār, the prime minister, opposed and routed him, and the prince was drowned in his flight. The successful general next defeated and slew two other brothers, Khujistah Akhtār Jahān-Shāh and Rafī-ash-Shān, and placed the surviving of the four sons of Bahādur [i.e. Mu'izz-ud- dīn] on the throne with the title of Jahāndār ("World-owner"). The new Emperor was an irredeemable poltroon and an abandoned debauchee.' (The History of the Moghul Emperors of Hindustan illustrated by their Coins, Constable, 1892, and in Introd. to B. M. Catal. of Moghul Emperors, same date.)

He was killed in 1713, and was succeeded by Farrukh-sīyar, the son of Azīm-ush-Shān. The chronology is as follows:-

The question concerning the exact date from which the beginning of Aurangzēb's reign should be reckoned is obscured by the conflict of authorities and has given rise to much discussion. The results may be stated briefly as follow:—

Aurangzēb formally took possession of the throne in a garden outside Delhi on the 1st Zū'l Q'adah, A.H. 1068, July 31, A.D. 1658, but subsequently orders were passed to antedate the beginning of the reign to 1st Ramazān in the same year, equivalent to June 2, 1658. After the destruction of Shāh Shujā, Aurangzēb returned to Delhi in May, A.D. 1659, and was again enthroned with full ceremonial on June 15, 1659 (= A.H. 1069). Some authors consequently assume the accession to have taken place in 1659. But the reign certainly began in A.D. 1658, and should be reckoned as running from the official date, June 2 of that year. The dates given above are in New Style (N.S.). If recorded in Old Style (O.S.) they would be ten days earlier. (See Irvine and Hoernle in J.A.S.B., Part I, vol. lxii (1893), pp. 256-67; and Irvine, in Ind. Ant., vol. xl (1911), pp. 74, 75.)

506

The author invariably ignores the fact that daughters and other female relatives inherit under Muhammadan law.

507

Hindoo law does not ordinarily recognize any right of succession for daughters, and so differs essentially from the law of Islam. The exceptions to this general rule are unimportant.

508

The experience of most officials does not confirm this statement.

509

The statement now requires modification. After the Central Provinces were constituted in 1861, the principle of succession by primogeniture was maintained only in the Hoshangābād, Chhindwāra, Chāndā, and Chhattīsgarh Districts. But even there the legal effect of the restrictions on alienation and partition is 'not quite free from doubt' (I.G. 1908, x. 73). The tendency of the law courts is to apply everywhere uniform rules taken from the Hindoo law books.

510

'See ante, Chapter 10, notes 10, 16. The gradual conversion of tenure by leases from Government into proprietary right in land has brought the land under the operation of the ordinary Hindoo law, and each member of a joint family can now enforce partition of the land as well as of the stock upon it. The evils resulting from incessant partition are obvious, but no remedy can be devised. The people insist on partition, and will effect it privately, if the law imposes obstacles to a formal public division.

511

These remarks attribute too much System to the disorderly working of an Asiatic despotism. No institution resembling the formal 'ban of the empire' ever really existed in India.

512

The Rājās at Simla might now be considered by some people as an encumbrance.

513

The author could not foresee the gallant service to be rendered by the Chiefs of the Panjāb and other territories in the Mutiny, nor the institution of the Imperial Service Troops. Those troops, first organized in 1888, in response to the voluntary offers made by many princes as a reply to the Russian aggression on Panjdeh, are select bodies, picked from the soldiery of certain native states, and equipped and drilled in the European manner. Cashmere (Kāshmīr) and many States in the Panjāb and elsewhere furnish troops of this kind, officered by local gentlemen, under the guidance of English inspecting officers. The Kāshmīr Imperial Service Troops did excellent service during the campaign of 1892 in Hunza and Nagar. the System so happily introduced is likely to be much further developed. In 1907 the authorized strength was a little over 18,000 (I.G., iv (1907), pp. 87, 373).

514

'In Rome, as in Egypt and India, many of the great works which, in modern nations, form the basis of gradations of rank in society, were executed by Government out of public revenue, or by individuals gratuitously for the benefit of the public; for instance, roads, canals, aqueducts, bridges, &c., from which no one derived an income, though all derived benefit. There was no capital invested, with a view to profit, in machinery, railroads, canals, steam- engines, and other great works which, in the preparation and distribution of man's enjoyments, save the labour of so many millions to the nations of modern Europe and America, and supply the incomes of many of the most useful and most enlightened members of their middle and higher classes of society. During the republic, and under the first emperors, the laws were simple, and few derived any considerable income from explaining them. Still fewer derived their incomes from expounding the religion of the people till the establishment of Christianity.

Man was the principal machine in which property was invested with a view to profit, and the concentration of capital in hordes of slaves, and the farm of the public revenues of conquered provinces and tributary states, were, with the land, the great basis of the aristocracies of Rome, and the Roman world generally. The senatorial and equestrian orders were supported chiefly by lending out their slaves as gladiators and artificers, and by farming the revenues, and lending money to the oppressed subjects of the provinces, and to vanquished princes, at an exorbitant interest, to enable them to pay what the state or its public officers demanded. The slaves throughout the Roman empire were about equal in number to the free population, and they were for the most part concentrated in the hands of the members of the upper and middle classes, who derived their incomes from lending and employing them. They were to those classes in the old world what canals, railroads, steam-engines, &c., are to those of modern days. Some Roman citizens had as many as five thousand slaves educated to the one occupation of gladiators for the public shows of Rome. Julius Caesar had this number in Italy waiting his return from Gaul; and Gordianus used commonly to give five hundred pair for a public festival, and never less than one hundred and fifty.

In India slavery is happily but little known;[a] the church had no hierarchy either among the Hindoos or Muhammadans; nor had the law any high interpreters. In all its civil branches of marriage, inheritance, succession, and contract, it was to the people of the two religions as simple as the laws of the twelve tables; and contributed just as little to the support of the aristocracy as they did. In all these respects, China is much the same; the land belongs to the sovereign, and is minutely subdivided among those who farm and cultivate it—the great works in canals, aqueducts, bridges, roads, &c., are made by Government, and yield no private income. Capital is nowhere concentrated in expensive machinery; their church is without a hierarchy, their law without barristers-their higher classes are therefore composed almost exclusively of the public servants of the Government. The rule which prescribes that princes of the blood shall not be employed in the government of provinces and the command of armies, and that the reigning sovereign shall have the nomination of his successor, has saved China from a frequent return of the scenes which I have described. None of the princes are put to death, because it is known that all will acquiesce in the nomination when made known, supported as it always is by the popular sentiment throughout the empire. [W. H. S.]

a. the anthor's statement that in the year 1836 slavery was 'but little known in India' is a truly astonishing one. Slavery of various kinds—racial, predial, domestic—the slavery of captives, and of debtors, had existed in India from time immemorial, and still flourished in 1836. Slavery, so far as the law can abolish it, was abolished by the Indian Act v of 1843, but the final blow was not dealt until January l, 1862, when sections 370, &c., of the Indian Penal Code came into force. In practice, domestic servitude exists to this day in great Muhammadan households, and multitudes of agricultural labourers have a very dim consciousness of personal freedom. The Criminal Law Commissioners, who reported previous to the passage of Act v of 1843, estimated that in British India, as then constituted, the proportion of the slave to the free population varied from one-sixth to two-fifths. Sir Bartle Frere estimated the slave population of the territories included in British India in the year 1841 as being between eight and nine millions. Slaves were heritable and transferable property, and could be mortgaged or let out on hire. The article 'Slave' in Balfour, Cyclopaedia (3rd ed.), from which most of the above particulars are taken, is copious, and gives references to various authorities. The following works may also be consulted: The Law and Custom of Slavery in British India, by William Adam, 8vo, 1840; An Account of Slave Population in the Western Peninsula of India, 1822, with an Appendix on Slavery in Malabar; India's Cries to British Humanity, by J. Peggs, 8vo, 1830; and E.H.I., 3rd ed. (1914), pp. 100, 178, 180, 441.

515

In Akbar's time there were thirty-three grades of official rank, and the officers were known as 'commanders of ten thousand', 'commanders of five thousand', and so on. Only princes of the blood royal were granted the commands of seven thousand and of ten thousand. The number of troopers actually provided by each officer did not correspond with the number indicated by his title. The graded officials were called mansabdārs, no clear distinction between civil and military duties being drawn (The Emperor Akbar, by Count Von Noer; translated by Annette S. Beveridge, Calcutta, 1890, vol. i, p. 267).

516

Diodorus Siculus has the same observation. 'No enemy ever does any prejudice to the husbandmen; but, out of a due regard to the common good, forbear to injure them in the least degree; and, therefore, the land being never spoiled or wasted, yields its fruit in great abundance, and furnishes the inhabitants with plenty of victual and all other provisions.' Book II, chap. 3. [W. H. S.] These allegations certainly cannot be accepted as accurate statements of fact, however they may be explained. See E.H.I., 3rd ed. (1914), p. 442.

517

The rapid recovery of Indian villages and villagers from the effects of war does not need for its explanation the evocation of 'a spirit of moral and political vitality'. The real explanation is to be found in the simplicity of the village life and needs, as expounded by the author in the preceding passage. Human societies with a low standard of comfort and a simple scheme of life are, like individual organisms of lowly structure and few functions, hard to kill. Human labour, and a few cattle, with a little grain and some sticks, are the only essential requisites for the foundation or reconstruction of a village.

518

Golconda was taken by Aurangzēb, after a protracted siege, in 1677. Bījāpur surrendered to him on the 15th October, 1686. The vast ruins of this splendid city, which was deserted after the conquest, occupy a space thirty miles in circumference. The town has partially recovered, and is now the head- quarters of a Bombay District, with about 24,000 inhabitants. Sivājī, the founder of the Marāthā power, died in 1680.

519

The Indore and Barodā States still survive, and the reigning chiefs of both have frequently visited England, and paid their respects to their Sovereign. Bhōnslā was the family name of the chiefs of Berār, also known as the Rājās of Nāgpur. The last Rājā, Raghojī III, died in December 1853, leaving no child begotten or adopted. Lord Dalhousie annexed the State as lapsed, and his action was confirmed in 1864 by the Court of Directors and the Crown.

520

The State of Sātārā, like that of Nāgpur, lapsed owing to failure of heirs, and was annexed in 1854. It is now a district in the Bombay Presidency.

521

During the early years of the twentieth century a spirit of Marāthā nationalism has been sedulously cultivated, with inconvenient results.

522

This paragraph, and that next following, are, in the original edition, printed as part of Chapter 48, 'The Great Diamond of Kohinūr', with which they have nothing to do. They seem to belong properly to Chapter 47, and are therefore inserted here. The observations in both paragraphs are merely repetitions of remarks already recorded.

523

It need hardly be said that these fire-eaters no longer exist.

524

Nādir Shāh was crowned king of Persia in 1736, entered the Panjāb, at the close of 1738, and occupied Delhi in March 1739. Having perpetrated an awful massacre of the inhabitants, he retired after a stay of fifty-eight days, He was assassinated in May 1747.

525

Meshed, properly Mashhad ('the place of martyrdom'), is the chief city of Khurāsān. Nādir Shāh was killed while encamped there.

526

Ahmad Shāh defeated the Marāthās in the third great battle of Pānīpat, A.D. 1761. He had conquered the Panjāb in 1748. He invaded India five times.

527

In 1773.

528

Lūdiāna (misspelt 'Ludhiāna' in I.G., 1908) is named from the Lodī Afghāns, who founded it in 1481. The town is now the headquarters of the district of the same name under the Panjāb Government. Part of the district lapsed to the British Government in 1836, other parts lapsed during the years 1846 and 1847, and the rest came from territory already British by rearrangement of jurisdiction. Hyphasis is the Greek name for the Biās river.

529

The above history of the Kohinūr may, I believe, be relied upon. I received a narrative of it from Shāh Zamān, the blind old king himself, through General Smith, who commanded the troops at Lūdiāna; forming a detail of the several revolutions too long and too full of new names for insertion here. [W. H. S.] The above note is, in the original edition, misplaced, and appended to two paragraphs of the text, which have no connexion with the story of the diamond, and really belong to Chapter 47, to which they have been removed in this edition.

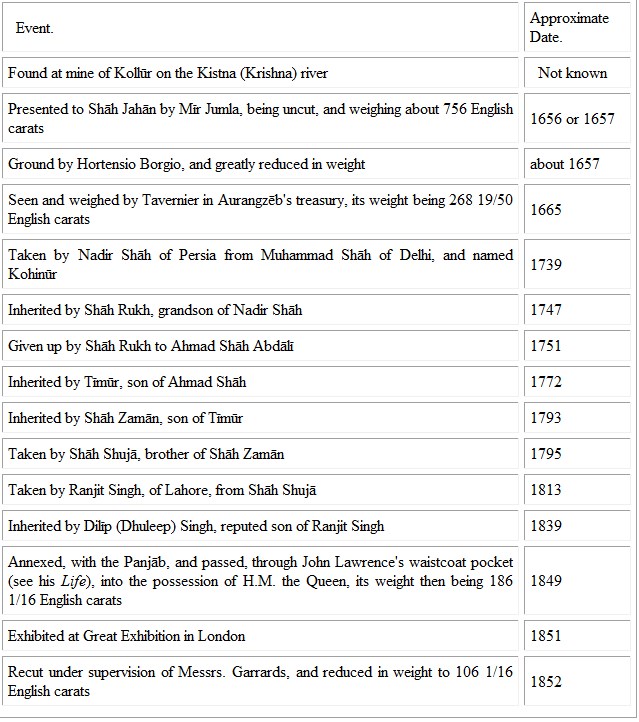

The author assumes the identity of the Kohinūr with the great diamond found in one of the Golconda mines, and presented by Amīr Jumla to Shāh Jahān. The much-disputed history of the Kohinūr has been exhaustively discussed by Valentine Ball (Tavernier's Travels in India: Appendix I (1), 'The Great Mogul's Diamond and the true History of the Koh-i-nur; and (2) 'Summary History of the Koh-i-nur'). He has proved that the Kohinūr is almost certainly the diamond given by Amīr (Mīr) Jumla to Shāh Jahān, though now much reduced in weight by mutilation and repeated cutting. Assuming the identity of the Kohinūr with Amīr Jumla's gift, the leading incidents in the history of this famous jewel are as follows;—

The difference in weight between 268 19/50 carats in 1665 and 186 1/16 carats in 1849 seems to be due to mutilation of the stone during its stay in Persia and Afghanistan.

530

The policy of the first Afghan War has been, it is hardly necessary to observe, much disputed, and the author's confident defence of Lord Auckland's action cannot be accepted.

531

For the characteristics of the Marāthās and Pindhārīs, see ante, Chapter 21, note 2.

532

Ante, Chapter 26, note 8, and Chapter 32, note 9.

533

Ante, Chapter 17, note 6.

534

A small principality, about seventy miles equidistant from Agra, Gwālior, Mathurā, Alwar, Jaipur, and Tonk. The attack on Karaulī occurred in 1813. Full details are given in the author's Report on Budhuk alias Bagree Decoits, pp. 99- 104.

535

Four hundred thousand rupees.

536

Ante, Chapter 33, note 15.

537

Seven hundred thousand rupees.

538

Raghugarh is now a mediatized chiefship in the Central India Agency, controlled by the Resident at Gwālior. Bajranggarh, a stronghold eleven miles south of Gūnā (Goonah), and about 140 miles distant from Gwālior, is in the Raghugarh territory.

539

Three hundred thousand and two hundred thousand rupees, respectively. Bahādurgarh is now included in the Isāgarh district of the Gwālior State.

540

I cannot find any mention of Lopar, if the name is correctly printed. Garhā Kota seems to be a slip of the pen for Garhā. Garhā Kota is in British territory, in the Sāgar District, C. P. But Garhā is a petty state, formerly included in the Raghugarh State. The town of Garhā is on the eastern slope of the Mālwā plateau in 25º 2' N. and 78º 3' E. (I.G., 1908, s.v.).

541

On the coronation or installation of every new prince of the house of Sindhia, orders are given to plunder a few shops in the town as a part of the ceremony, and this they call or consider 'taking the auspices'. Compensation is supposed to be made to the proprietors, but rarely is made. I believe the same auspices are taken at the installation of a new prince of every other Marāthā house. The Moghal invaders of India were, in the same manner, obliged to allow their armies to take the auspices in the sack of a few towns, though they had surrendered without resistance. They were given up to pillage as a religions duty. Even the accomplished Bābar was obliged to concede this privilege to his army. [W. H. S.]

In reply to the editor's inquiries, Colonel Biddulph, officiating Resident at Gwālior, has kindly communicated the following information on the subject of the above note, in a letter dated 30th December, 1892. 'The custom of looting some "Banias'" shops on the installation of a new Maharaja in Gwālior is still observed. It was observed when the present Mādho Rāo Sindhia was installed on the gadī on 3rd July, 1886, and the looting was stopped by the police on the owners of the shops calling out "Dohai Mādho Mahārājkī!" five shops were looted on the occasion, and compensation to the amount of Rs. 427, 4, 3 was paid to the owners. My informant tells me that the custom has apparently no connexion with religion, but is believed to refer to the days when the period between the decease of one ruler and the accession of his successor was one of disorder and plunder. The maintenance of the custom is supposed to notify to the people that they must now look to the new ruler for protection.

'According to another informant, some "banias" are called by the palace officers and directed to open their shops in the palace precincts, and money is given them to stock their shops. The poor people are then allowed to loot them. No shops are allowed to be looted in the bazaar.

'I cannot learn that any particular name is given to the ceremony, and there appears to be some doubt as to its meaning; but the best information seems to show that the reason assigned above is the correct one.

'I cannot give any information as to the existence of the custom in other Mahratta states.'

The custom was observed late in the sixth century at the birth of King Harsha-vardhana (Harsa-Caritā, transl, Cowell and Thomas, p. 111). Anthropologists classify such practices as rites de passage, marking a transition from the old to the new.

'Bania', or 'baniyā', means shopkeeper, especially a grain dealer; 'gadī', or 'gaddī', is the cushioned seat, also known as 'masnad', which serves a Hindoo prince as a throne; and 'dohāi' is the ordinary form of a cry for redress.

542

Ninety-two lākhs of rupees were then worth more than £920,000. The I.G. (1908) states the normal revenue as 150 lākhs of rupees, equivalent (at the rate of exchange of 1s. 4d. to the rupee, or R 15 = £1) to one million pounds sterling. The fall in exchange has greatly lowered the sterling equivalent.

543

The Bhīl tribes are included in the large group of tribes which have been driven back by the more cultivated races into the hills and jungles. They are found among the woods along the banks of the Nerbudda, Taptī, and Mahī, and in many parts of Central India and Rājputāna. Of late years they have generally kept quiet; in the earlier part of the nineteenth century they gave much trouble in Khāndēsh. In Rājputāna two irregular corps of Bhīls have been organized.

544

Daughter of Māhādajī Sindhia. She died in 1834. See post, Chapter 70.

545

'In 1886 the fort of Gwālior and the cantonment of Morār were surrendered by the Government of India to Sindhia in exchange for the fort and town of Jhānsī. Both forts were mutually surrendered and occupied on 10th March, 1886. As the occupation of the fort of Gwālior necessitated an increase of Sindhia's army, the Mahārājā was allowed to add 3,000 men to his infantry' (Letter of Officiating Resident, dated 30th Dec., 1892). In 1908 the Gwālior army, comprising all arms, including three regiments of Imperial Service Cavalry, numbered more than 12,000 men, described as troops of 'very fair quality' (I.G., 1908).

546

Ante, Chapter 26, note 8; Chapter 32, note 9; Chapter 49, note 2.

547

In Ramaseeana the author has fully described the practices of the Thugs in taking omens, and the feelings with which they regarded their profession. Similar information concerning other criminal classes is copiously given in the Report on Budhuk alias Bagree Decoits. See also Meadows Taylor, Confessions of a Thug, in any edition.