Полная версия

Полная версияBuffalo Land

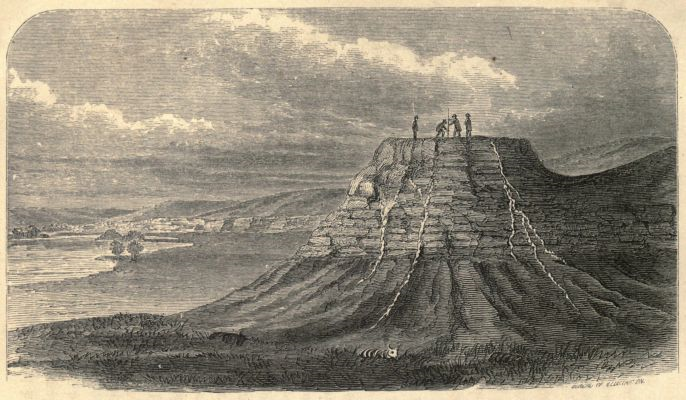

We fished with a hooked stick for some time, and were rewarded by bringing up a ragged blanket and a shattered gunstock. All around the rim of the opening were incrustations of salt, and the brackish water trickled over, and ran in little rivulets down the huge sides. At the base of the rock, a dead buffalo was fast in the mud, having died where he mired, while licking the Great Spirit's brackish altar.

WACONDA DA—GREAT SPIRIT SALT SPRING.

As no remarkable spot in Indian land should ever be brought before the public without an accompanying legend, I shall present one, selected out of several such, which has attached itself to this. To make tourists fully appreciate a high bluff or picturesquely dangerous spot, it is absolutely essential that some fond lovers should have jumped down it, hand-in-hand, in sight of the cruel parents, who struggle up the incline, only to be rewarded by the heart-rending finale. This, then, is

THE LEGEND OF WACONDAMany moons ago—no orthodox Indian story ever commenced without this expression—a red maiden, named Hewgaw, fell in love. (And I may here be permitted to quote a theory of Alderman Sachem's, to the effect that Eve's daughters generally fall into every thing, including hysterics, mistakes, and the fashions.) Hewgaw was a chief's daughter, and encouraged a savage to sue for her hand who, having scalped but a dozen women and children, was only high private or "big soldier." Chief and lover were quickly by the ears, and the fiat went forth that Wa-bog-aha must bring four more scalps, before aspiring to the position of son-in-law. This seemed as impossible as Jason's task of old. War had existed for some time, and, as there was no chance for surprises, scalp-gathering was a harvest of danger.

There seemed no alternative but to run for it, and so, gathering her bundle, Hewgaw sallied out from the first and only story of the paternal abode, as modern young ladies, in similar emergencies, do from the third or fourth. Through the tangled masses of the forest, the red lovers departed, and just at dawn were passing by the Waconda Spring, into whose waters all good Indians throw an offering. Wa-bog-aha either forgot or did not wish to do so. Instantly the spring commenced bubbling wrathfully. So far, the Great Spirit had guided the lovers; now, he frowned. An immense column of salt water shot out of Waconda high into air, and its brackish spray dashed furiously into the faces of Wa-bog-aha and Hewgaw, and drove them back.

The saltish torrent deluged the surrounding plains—putting every thing into a pretty pickle, as may well be imagined. The ground was so soaked that the salt marshes of Western Kansas still remain to tell of it, and, a portion of the flood draining off, formed the famous "salt plains." Along the Arkansas and in the Indian Territory, the incrustations are yet found, covering thousands of acres. The Kansas River, for hours, was as brackish as the ocean, its strangely seasoned waters pouring into the Missouri, and from thence into the Mississippi. It was this, according to tradition, which caused such a violent retching by the Father of Waters, in 1811. The current flowed backward, and vessels were rocked violently—phenomena then ascribed by the materialistic white man to an earthquake.

Too late the luckless pair saw their mistake, and started for the summit of Waconda, just as the angry father put in his very unwelcome appearance. Had they avoided looking toward the spring, all, perchance, might yet have been well. Without exception, the medicine men had written it in their annals that no eye but their own must ever gaze back at Waconda, after once passing it. Tradition explains that this was to avoid semblance of regret for gifts there offered the Great Spirit. Sachem, however, is of the opinion that in giving these orders the medicine men had the gifts in their eye, and simply wished time to put them in their pockets. Hewgaw could not resist the temptation to peep. Immediately around the rock all was quiet, while without the narrow circle the descending torrents were dashed fiercely by the winds. The beasts of the plains, in countless numbers, came rushing in toward the Waconda, their forms white with coatings of salt, and probably representing the largest amount of corned meat ever gathered in one place.

All the brute eyes—knightly elk, kingly bison, and currish wolves—were turned toward the top where Wa-bog-aha and Hewgaw stood, casting their valuables, as appeasing morsels, into the hissing spring. It refused to be quieted. Suddenly, the lovers were nowhere visible, and the salt storm ceased. Nothing could be found by the afflicted father, except a tress of his daughter's hair—perhaps her chignon.

The old chief declared that, just as the end was approaching, the clouds were full of beautiful colors, and the air glittered with diamonds. The white man's science, however, coldly assumes that these appearances were only the rainbows and their reflections, playing amidst the crystal salt shower.

Sabbath morning dawned upon our camp, and according to our usual custom, we lay by for the day. At ten o'clock, the Professor read the morning service. It must have been a strange scene that we presented, while uncouth teamsters and all—our family-pew the wide valley, with its seats of stones, and logs—sat listening to the beautiful language that told how the faith of which Christianity was born was cradled in a land as primitive and desolate as that which we were traversing. There, the wild Arab hordes hovered over the deserts; here, America's savage tribes do the same over the plains.

Our priest stood near one of Nature's grandest altar pieces, "Waconda Da." Reverence from the most irreverent is secured among such scenes and solitudes. Away from his fellows, man's soul instinctively looks upward, and yearns for some power mightier than himself to which to cling. The brittle straw of Atheism snaps when called upon for support under these circumstances, and the blasphemy which was bold and loud among the haunts of men, here is hushed into silence, or even awed into reverential fear.

The Professor improved the opportunity to deliver an excellent discourse upon the wonderful evidences of God's power which geology is daily revealing. His peroration was quite flowery, and in a strain very much as follows:

"Science is yet in its infancy, and many things which seem dark to us will be clear to our descendants. Future generations will doubtless wonder at our boiler explosions, and our railroad accidents. Lightning expresses will be used only for freight, while machines navigating the air, at one hundred miles an hour, will carry the passengers. Steam, electricity, and the magnetic needle have all been open to man's appropriative genius ever since the world offered him a home, and yet he has only just now comprehended them. The future will see instruments boring thousands of feet into the earth in a day, and developing measures and mysteries which the world is not now ripe for understanding. Perhaps, the telescopes of another century may bring our descendants face to face with the life of the heavenly bodies, and give us glimpses of the inhabitants at their daily avocations. Who knows but that the beings who people other worlds in the infinite ocean of space around us, compared with which worlds our little planet is insignificant indeed, are able, by the use of more powerful instruments than any with which we are acquainted, to hold us in constant review? Our battles they may look upon as we would the conflicts of ants, and they wonder, perchance, why so quarrelsome a world is permitted to exist at all."

Next morning Sachem was up at daybreak, examining the spot where Hewgaw and Wa-bog-aha met their fate, and underwent their iridescent annihilation. His offering to their memory we found after breakfast, tacked up in a prominent position beside the spring. The inscription, evidently intended as a sort of epitaph, was written on the cover of a cracker-box, and struck me as so peculiar that I was at the pains of transcribing it among our notes. I give it to the reader for the purpose, principally, of showing the unconquerable antipathies of an alderman.

In MemoriamLot's wife, you remember, looked back,(What woman could ever refrain?)And instantly stood in her trackA pillar of salt on the plain.If all were thus cursed for the fault,Who peep when forbidden to look,The feminine pillars of saltCould never be written in book.Hewgaw was an Indian belleWhich no one could ring—she was fickle;Some scores of her lovers there fell(Where she did at last) in a pickle.Thus salt is the only thing knownEntirely certain of keepingFlesh of our flesh, bone of our bone,Out of the habit of peeping.Unless the tradition has lied,Our maiden may claim, with good reason,That she is a well-preserved bride,And certainly bride of a season.Wa-bog-aha big was a brave—The Great Spirit salted him down:Braves seldom get corned in the grave,They 're oftener corned in the town.My rhyming, you find, is saline,Quite brackish its toning and end;The moral—far better to pineThan wed and get "salted," my friend.Soon after sunrise we took our way down the river, intending to reach the Sydney farm on the following day, and there spend the necessary time in preparing our specimens for immediate shipment when we should arrive at Solomon City. The Professor made desperate efforts to appear entirely wrapped up in science, and his devotion to geology was something wonderful. Hitherto he had been inclined to urge us forward, but now he made a show of holding us back. Did he do so with a knowledge that our necessities for food and forage would be sufficient spur, and was he simply shielding his weak side from Sachem's attacks?

We had proceeded but a few miles on our journey, when the guide rode back, and reported fresh pony tracks across the road ahead of us. This was an unquestionable Indian sign, but as the trail seemed to be leading north, we took no precaution; our route was over a high divide, where ambushing was impossible.

Approaching Limestone Creek, the road wound down the face of a precipitous bluff, into the valley below. We had just commenced the descent, when the now familiar cry of "Injuns!" came back from the men in front, and following closely on the cry we heard the echoing report of firearms. We looked in the direction of the sound, and saw close to the trees an emigrant wagon, while beyond it, but at fully one hundred yards' distance, four or five Indians were riding back and forth in semi-circles, and firing pistols. The emigrant stood beside his oxen, with rifle in readiness, but apparently reserving his fire.

"That man knows his biz!" exclaimed our guide, as he urged the teams forward, that we might afford rescue. "Injuns never bump up agin a loaded gun."

A gleam of calico was visible in the wagon, and another rifle barrel, held by female hands, seemed peering out in front. The general aspect of the assailed outfit reminded us strongly of the Sydney family, and suspicion was strengthened by a very unscientific yell from the Professor, as he started off at break-neck speed down the bluff for a rescue, with no other weapon whatever in his hand than a small hammer he had just been using for breaking stones. Mr. Colon seemed equally demented, following close upon Paleozoic's heels with a bug-net. Shamus, at the moment, happened to be astride his donkey, and giving an Irish war-whoop which reached even to the scene of combat, straightway charged over the limestone ledges in a cloud of white dust. Our appearance upon the scene was a surprise to Lo. The Indians stood not upon the order of their going, but "lit out on the double-quick," as our guide expressed it, and were soon out of sight.

We found that the emigrants were named Burns, the family comprising the parents and their two children. The man stated that he had no fear of the savages. He had been twice across the plains, and made it a rule never to throw a shot away. "If they can draw your fire," said he, "the fellows will charge. But they don't want to look into a loaded gun." Mrs. Burns had come to her husband's rescue with an expedient worthy the wife of a frontiersman. Having no gun, she pointed from under the canvass the handle of a broom. This, being woman's favorite weapon, was handled so skillfully that the savages imagined it another rifle. In our log-book she was chronicled at once as fully the equal of that revolutionary hero, who one evening made prisoner of a British officer, by crooking an American sausage into the semblance of a pistol, and presenting it at the Englishman's breast.

There were two of our party who did not rejoice as they should have done, after rendering such timely aid to the Burns family. How romantic had the rescued party only proved to be the one which was at first suspected!

Where this little scene occurred, there are homesteads now, which will soon develop into thrifty farms. The blessing of a railroad can not be long deferred. A year, a month, even a week sometimes, makes wonderful changes in Buffalo Land, when the tide of immigration is rolling forward upon it. Before the present year is ended, the beautiful valley of Limestone Creek will be teeming with civilized life, and the savage red man, there is good reason to believe, has departed from it forever.

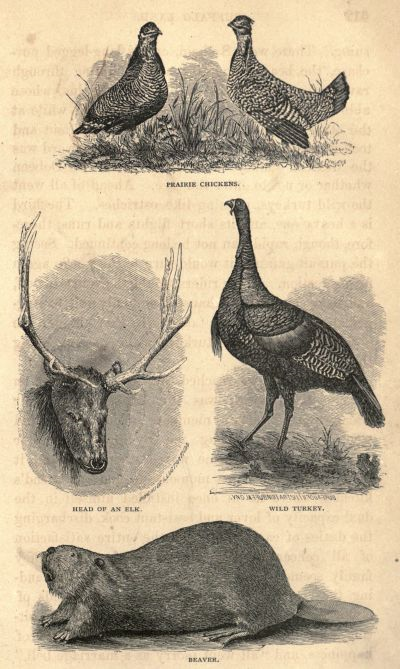

After bidding the Burns family good-bye, we traveled without further adventure until near noon, when the guide rode back, and directed our attention to some elk, which he pointed out, some distance ahead. The bodies of the herd were hidden by a ridge, but above its brown line we could plainly see their great antlers, looking like the branches of trees, moving slowly along. There was but one method of getting near the game, and that was immediately adopted. Up the side of the sloping ridge we carefully crawled, and, reaching the summit, peeped over. Half a dozen big antlered fellows, and as many does, were feeding along the slope below. Only one of them, a splendid male, was within shooting distance at all, and even for it the range was long. The guide and Muggs fired together, breaking the poor creature's shoulder.

What a startled stare the noble animals flashed back at the crack of the rifles, and how quickly they disappeared. Their trot was perfectly grand—great, firm strokes which seemed to fairly fling the bodies onward. We had hardly time to realize having fired, when their tails bade us distant adieu. It is said that no horse can keep up with the trot of the elk. If charged upon suddenly, however, from close quarters, he is frightened into an awkward gallop, and may then be overtaken easily.

Our wounded game looked formidable, and we approached cautiously. He made several efforts to run, but each time fell forward, in plunging slides, on his nose and side, rubbing the hair from the latter, and daubing the ground with blood from his nostrils. Muggs felt free to confess that even the pampered stags of England, when perilously roused from their well-kept glens, by over-fed hunters in killing coats and boots, never presented such a picture of wild beauty and agony, colored just the least bit with danger. At this "kill" we lost our black hound. Tempted to incaution by the sight of the noble elk standing wounded and at bay, or else excited by its blood, the dog sprang forward. A chance blow of the massive horns knocked him over, and in an instant more the beast had stamped him to death.

We finished the elk by a united volley, and added him to our trophies. The horns, resting upon their tips, gave space for one of our Mexicans, five feet two in stature, to pass beneath them erect. Elk hairs are remarkably elastic. Single ones obtained from this specimen stretched by trial with the fingers, and detached from the skin so easily that the latter seemed worthless.

During the day we found and secured the remains of two saurians—one about eight and the other ten feet in length, and also the tooth of a fossil horse, quite a number of curious bubble-shaped pieces of iron pyrites, and some fine petrifactions, in the way of butternuts and fragments of trees. The soft, white limestone, mentioned more than once before in this record of our expedition, appeared along our paths in fine outcrops, and contained very perfect fossil shells.

Abe, our guide, told us that a year or two previous, during a winter of unusual severity, he had found a flock of Rocky Mountain sheep feeding near the Solomon. This was the only instance which came to our knowledge of that animal having been seen upon the plains.

We had an amusing experience, before night, with turkeys, hunting them in novel style. The birds were wild from recent pursuit, and, the instant they saw us, would leave the narrow fringe of timber, and run off into the ravines. Then would commence a ludicrous chase, each rider plying spurs, and pursuing. There went Sachem, on his long-legged purchase, the beast staggering and stumbling through ravines; and Semi also, upon Cynocephalus, whose abbreviated tail was hoisted straight in air, while at the other extremity his nose stretched well out and took in air under asthmatic protests. Rearward was the Mexican donkey, arguing the point with Dobeen whether or not to enter the race. Ahead of all went the wild turkeys, running like ostriches. The bird is a heavy one, and its short flights and runs, therefore, though rapid, can not be long continued. Seeing the pursuit gaining, it would turn to the woods again for protection. Other riders would there head it off, and soon, completely exhausted and only able to stagger along, it was easily taken. In this manner, we obtained over twenty turkeys while passing along the river.

MORE OF OUR SPECIMENS—PHOTOGRAPHED BY J. LEE KNIGHT, TOPEKA, KANS. PRAIRIE CHICKENS. HEAD OF AN ELK. WILD TURKEY. BEAVER.

That evening we reached the little settlement on the Solomon, which was the Canaan of all our wanderings to certain members of our party, and went into camp among the Sydneys and their neighbors. Our welcome was a warm one, and it took Shamus but a few moments to find our friend's kitchen, where he at once installed himself in the dual capacity of lover and assistant cook, discharging the duties of each position to the entire satisfaction of all concerned. Our supper with the Sydney family seemed like civilization again, notwithstanding that we were still on the uttermost bounds of civilized manners and customs. The Professor, sitting next to Miss Flora, was the very picture of happiness, and "all went merry as a marriage bell." Even Sachem ceased to sulk before the meal was ended.

At dusk, as we were assuring ourselves by personal inspection that the camp was in proper order, a familiar form came stalking toward us in the gathering gloom. "Tenacious Gripe!" cried the Professor; and so it was. Our friend's ribs had been repaired, and he was now on a mission along the Solomon river, holding railroad meetings in the different counties. The progressive westerner, when he has nothing else to do, is in the habit of starting out on a tour for the purpose of inducing the dear people to vote county bonds for a new railroad, and such a westerner was Gripe.

CHAPTER XXIX

OUR LAST NIGHT TOGETHER—THE REMARKABLE SHED-TAIL DOG—HE RESCUES HIS MISTRESS, AND BREAKS UP A MEETING—A SKETCH OF TERRITORIAL TIMES BY GRIPE—MONTGOMERY'S EXPEDITION FOR THE RESCUE OF JOHN BROWN'S COMPANIONS—SCALPED, AND CARVING HIS OWN EPITAPH—AN IRISH JACOB—"SURVIVAL OF THE FITTEST"—SACHEM'S POETICAL LETTER—POPPING THE QUESTION ON THE RUN—THE PROFESSOR'S LETTER.

Supper over, we made an engagement with our hospitable friends for their presence at a sort of "state dinner" we proposed giving the next day, and then returned to our own camp. A number of the settlers soon came strolling in, and among them one bringing a most remarkable dog, of the "shed-tail" variety. The animal was well known to fame in that section, for having attacked some Indians who had taken his mistress captive and were endeavoring to place her upon one of their ponies, and so delaying them that the neighbors were able to arrive and give rescue. It was claimed that thirty shots were fired at him without effect, which, if true, proved that either those Indians were exceedingly bad marksmen, or that the small fraction of caudal appendage which the beast possessed acted as a protective talisman.

We had often seen dogs without tails, but previous to this had always supposed that a depraved human taste, not nature, was at the root of it. Tail-wagging we had considered as much the born prerogative of a dog as a laugh is that of man. It is true some men do not laugh, but the child did. A dog's tail embodies his laughing faculty, or rather one might call it a canine thermometer. It rises and falls with his feelings, in moments of depression going down to zero between his legs, and again rising when the canine temperature becomes more even.

"That thar dorg, stranger, is of the shed-tail variety," said its owner, when we solicited information. "Whole litter had nothin' but stumps. Killed most on 'em off, 'cause, havin' nothin' to wag, visitin' people couldn't tell whether they was goin' to bite, or be pleased. Some time ago, a travelin' school-teacher giv' him a plaguy Latin name, but we call him Shed, for short. He knows, just as well as you and I, that he 's in the wrong, latterly, and as soon as you look at him, or touch where the tail ought ter be, he hides and howls. He 's sensitive as a human."

Saying this, our new acquaintance leaned over the dog, which was lying asleep, and gave the animal what he called a "latterly touch." Although it was but the gentle contact of a finger tip, the poor creature jumped up, uttered a dismal howl, and fled off among the wagons.

"That dorg," continued the owner, "would be one of the best critters out, if it wasn't for his short cut. He 'll fight Injuns, or wild cats, and take any amount of blows on his head, if they 'll only avoid his misfortin.'"

We remarked that he seemed to have been shot in the side, some time.

"Yes, got a whole charge of quail shot slapped inter him. You see the way it was, wer this. Most every section has one or two scraggy, rattle-brained fellers, allers loungin' round, takin' free drinks, and starvin' ther families. Whar we come from was one of this sort, never of no account to no one. We had a temperance meetin' one day, and this Hib, as they called him, wer opposed to it. He was afraid they 'd shut up Old Bung's whisky shed. Well, we was all a gathered, listenin' to the serpent and its poisoned sting, and that sort o' thing, and had about concluded to go for Old Bung, when that contrairy, ornery Hib broke us up. He goes and gets a fresh coon skin, and sneaks all round the school-house, draggin' it arter him, and makin' a sort o' scented circle. Then he goes and gets Shed Tail there, who was powerful on coons, and sets him on that thar track. Shed give just one sniff, and opened right out. The way he shied round that school-house wer a sin. In five minutes, all the dogs of the village were at his heels, and goin' round that circle like the spokes in a wheel.

"It was just a round ring of the loudest yelling you ever heard. Every dog thought the one just ahead of him had the coon. All the meetin' folks come a pourin' out, with sticks and chairs, and what with beatin' and coaxin' they got all off the trail but old Shed. Half the people went to chasin' that dorg, while the balance held onto the others. But Shed just stuck to that coon track, like all possessed, dodgin' atween our legs, or sheerin' off, and catchin' ther trail agin just beyond. He finally upset Old Squire Bundy's wife, and the Squire got mad, and slapped some No. 7 into his ribs."

The shed-tail's owner, waxing more and more eloquent with his subject, had just commenced the narrative of another Indian battle in which his favorite had figured, when we became interested in a wordy political combat between Tenacious Gripe and a genuine specimen of the "reconstructed," the first and only one of that genus that we saw in Kansas. His clothes had the famous butternut dye, and his shirt bosom was mapped into numerous creeks and rivers by the brown stains of tobacco overflows. The dispute waxed warm, and grew more and more prolific of eloquence. At length, the reconstructed beat a retreat, and our orator was left in triumphant possession of the field.