Полная версия

Полная версияBuffalo Land

COLON AND SEMI-COLON.

DAVID PYTHAGORAS, M. D.

Genuine Muggs was an Englishman. The antipodes of Tammany Sachem, who would not believe any thing, Muggs swallowed every thing. He had already absorbed so much in this way that he knew all about the United States before visiting it. Given half a chance, he would undoubtedly have told the savage more about the latter's habits than the aborigine himself knew. It was positively impossible for him to learn any thing. His round British body was so full of indisputable facts that another one would have burst it. In the Presidential alphabet, from Alpha Washington to Omega Grant, he knew all of our rulers' tricks and trades, and understood better the crooked ways of the White House than our own talented Jenkins.

British phlegm incased his soul, and British leather his feet. From heel to crown he was completely a Briton. His mutton-chop whiskers came just so far, and the h's dropped in and out of his utterings in a perfectly natural way. In the Briton's alphabet, Sachem used to remark, the I is so big that it is no wonder the H is often crowded out.

Muggs was a fair representative of the average Englishman who has traveled somewhat. The eye-teeth of these persons are generally cut with a slash, and they are forever after sore-mouthed. For a maiden effort they never suck knowledge gently in, but attempt a gulp which strangles. The consequence of this hasty acquiring is a bloated condition. The partly-traveled Briton seems, at first acquaintance, full and swollen with knowledge; but should the student of learning apply the prick, the result obtained will generally prove to be—gas.

Over our great country, some of the family of Muggs meet one at every turn. Often they scurry along solitarily, but occasionally in groups. In the former case they are unsocial to every body—in the latter to every body except their own party. The bliss which comes from ignorance must be of a thoroughly enjoyable nature, for the Muggses certainly do enjoy themselves. They will pass through a country, remaining completely uncommunicative and self-wrapped, and know less of it after six months' traveling than an American in two. The professor says he has met them in the lonely parks of the Rocky Mountains and in the fishing and hunting solitudes of the Canadas. If they have been an unusually long time without seeing a human being, they may possibly catch at an eye-glass and fling themselves abruptly into a few remarks. But it is in a tone which says, plainer than words, "No use in your going any further, man; I have absorbed all the beauties and knowledge of this locality."

ONE OF THE MUGGSES.

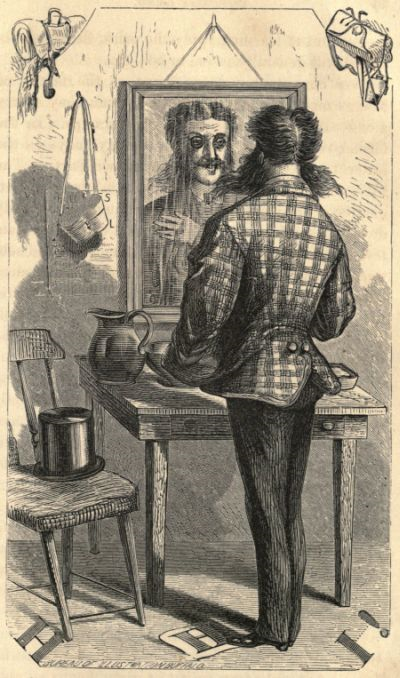

It is a rare treat to see a coach delivered of Muggs at a country inn. "Hi, porter, look hout for my luggage, you know. Tell the publican some chops, rare, and lively now, and a mug of hale, and, if I can 'ave it, a room to myself." If the latter request is granted, and you are inquisitive enough to take a peep, you may see Muggs sturdily surveying himself in the glass, and giving certain satisfied pats to his cravat and waistcoat, as if to satisfy them that they covered a Briton. Could the mirror which reflects his face also reflect his thoughts, they would read about as follows: "Muggs, you are a Briton, and this hotel must be made aware of the fact. Whatever you do, be guilty of no un-English act while in this outlandish land. Your skin is now full of knowledge, and let not other travelers, like so many mosquitoes, suck it from you. Your forefathers blessed their eyes and dropped their h's, and so must you." And perhaps by this time, if the chops have arrived, he dines in seclusion and, by so doing, loses a fund of information which his fellow-travelers have obtained by common exchange.

Again on the way, Muggs nestles in a corner of the coach and acts strictly on the defensive, indignantly withdrawing his square-toed, thick-soled English shoes, should neighboring feet attempt to hobnob with them. On a trip through Buffalo Land, however, it is difficult for one of her Britannic Majesty's subjects to maintain the national dignity. But this fact Genuine Muggs—our Muggs—evidently did not know. Had he known it, he would never have gone with us in the world.

Another of our party rejoiced in the appellation of "Colon." He obtained this title because his eccentric specialities of character several times came very near putting if not a full stop, at least the next thing to it, upon the particular page of history which our party was making. Longitudinally, Mr. Colon was all of five feet eleven; in circumference, perhaps a score or so of inches. He possessed a fair share of oddities, and what is better an equally fair one of dollars. The hemispheres of his philanthropic brain seemed equally pre-empted by philosophy and bugs. Engaging in some immense work for the amelioration of mankind, he would pursue it with ardor, dwell upon it with unction, and then suddenly leave it, half finished, to capture a rare spider. Philosophy and Entomology had constant combat for Colon, and victory tarried with neither long enough for the seat of war to be cultivated and blossom with any luxuriance. At the time he joined our party one of his grandest charitable projects had lately died in a very early period of infancy, entirely supplanted in his affections for the time being by the prospect of a chase after Brazilian insects. During our journey it was no uncommon thing for us to see his thin form all covered with bugs and reptiles, which had crawled out of the collecting boxes carried in his pockets. If this meets our friend's eye, let him bear no malice, but reflect, in the language of his own invariable answer to our remonstrances, "It can't be helped." Should the public parade of his faults be disagreeable, he can suffer no more from them now than we did in the past, and may perhaps call them into closer quarters for the future.

Mr. Colon's son, of two years less than a score, we dubbed Semi-colon, as being a smaller edition, or to be exact, precisely one-half of what the senior Colon was. So perfect was the concord of the two that the junior had fallen into a chronic and to us amusing habit of answering "Ditto" to the senior's expressions of opinion. Divide the father's conversation by two, add an assent to every thing, and the result, socially considered, would be the son. It may readily be seen, therefore, why the professor for short should call him, as he nearly always did, "Semi."

Shamus Dobeen, our cook and body-servant, according to his own account, was the child of an impoverished but noble Irish family. Indeed, we doubt if any Irishman was ever promoted from shovel laborer to body-servant without suddenly remembering that he was "descinded" from a line of kings. At the time Shamus was added to the population of Ireland, the patrimonial estate had dwindled down to a peat bog. As this soon "petered out," Shamus went from the exhausted moor into the cold world. He had been by turns expelled patriot, dirt disturber on new railroads, gunner on a Confederate cruiser, and high private in a Union regiment. The position of gunner he lost by touching off a piece before the muzzle had been run out, in consequence of which part of the vessel's side went off suddenly with the gun. Captured, he readily became a Union soldier, and could, without doubt, have transformed himself into a Cheyenne, or a Patagonian, had occasion for either ever required.

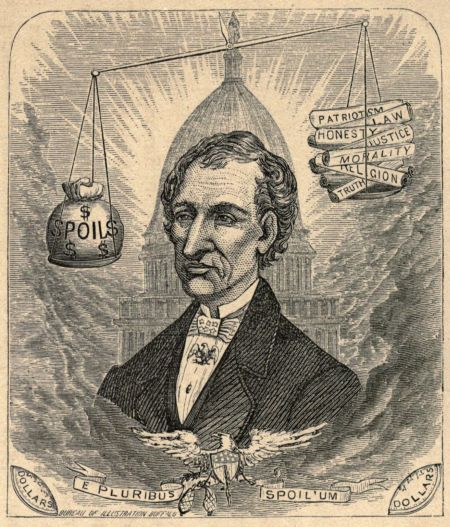

While in Topeka, our party made the acquaintance of Tenacious Gripe, a well-known Kansas politician, and who attached himself to us for the trip. Every person in the State knew him, had known him in territorial times, and would know him until either the State or he ceased to be.

Flung headlong from somewhere into Kansas during the "border ruffian" period, he would probably have passed as rapidly out of it had he been allowed to do so peaceably. But as the slavery party endeavored to push him, he concluded to stick. At that particular time, he was a moderate Democrat or conservative Republican, and consequently had no particular principles. But the slavery party supposed he had, and to them accordingly he became an object of suspicion. They assumed the aggressive, and he at once resolved into a staunch Republican. Had the latter first struck him, he would have been as staunch a Democrat. And Gripe has never known how near he came to being the latter. The Republicans had just decided to order him out of the state as a border ruffian spy, when the Democrats took action and did so for his not being one. Those were troublous times. He went to the front at once in the antislavery ranks, and has stayed there ever since. Sore-headed men are apt to become famous. There were those in our late war who were kicked by adversity into the very arms of Fame.

Our friend had been in both the upper and lower houses of the State Legislature, and had rolled Congressional logs, moreover, until he was hardly happy without having his hands on one.

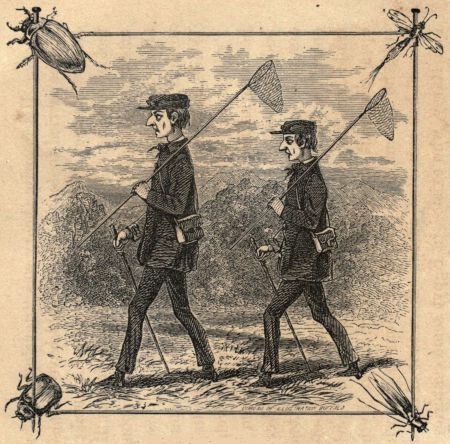

SHAMUS DOBEEN—HIS CARD.

HON. T. GRIPE (BEATIFIED).

CHAPTER III

THE TOPEKA AUCTIONEER—MUGGS GETS A BARGAIN—CYNOCEPHALUS—INDIAN SUMMER IN KANSAS—HUNTING PRAIRIE CHICKENS—OUR FIRST DAY'S SPORT.

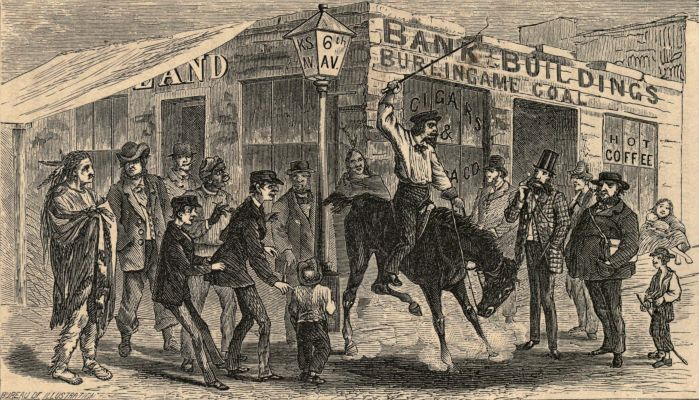

We had three or four days to spend in Topeka, as it was there that we were to purchase our outfit for the buffalo region. With the latter purpose in view, we were wandering along Kansas Avenue the next morning, when a horseman came furiously down the street, shouting, at the top of his lungs, "Sell um as he wars har!" Semi hastily retreated behind Mr. Colon, thinking it might be a Jayhawker, while the professor adjusted his glasses.

Muggs said the individual reminded him of the famous charge at Balaklava. Muggs had never seen Balaklava, but other Englishmen had, which answered the same purpose.

The equestrian proved to be a well-known auctioneer of Topeka, who may be discovered at almost any time tearing through the streets on some spavined or bow-legged old cob, auctioneering it off as he goes. His favorite expression is, "I'll sell um as he wars har." What particular selling charm lies concealed in this announcement even Gripe could not tell. Sachem thought that possibly he had been brought up at some exposed frontier post, where, on account of Indian prejudices, wearing hair is a rare luxury. To say there that a man was still able to comb his own scalp-lock denoted an extraordinary state of physical perfection. Expressions of praise for humans are often applied to horses, and so, perhaps, the one in question. "I have heard," quoth our alderman, in support of this assertion, "Fitz say of a belle, at a charity ball, what a 'bootiful cweature;' and I have heard him, the day after, in his stable, say the same thing of his horse."

That horse-auction was a sight worth seeing. The crowd collected most thickly on the corner of Kansas Avenue and Sixth Street, and before it the cob came to a stand. And it was a stand—as stiff and painful as that of a retired veteran put on dress parade. The limbs would have had full duty to perform in supporting the carcass alone, which had evidently been in light marching order for years past. The additional weight of the auctioneer must certainly have proved altogether too much, had not the horse heard, for the first time, of the wonderful qualities with which he was still endowed.

Seeing a whole corner, with gaping mouths, swallowing the statement that he was only six years old, reduced by hard work, and could, after three months grass, pull a ton of coal, he would have been a thankless horse indeed, which could not strain a point, or all his points, for such a rider.

"SPERIT, GENTLEMEN!"

And so, when the spurs suddenly rattled against his ribs, the old skin full of bones gave a snort of pain, which the auctioneer called "Sperit, gentlemen!" and away up the broad avenue he rolled, at a speed which threatened to break the rider's neck, and his own legs as well. His tail having been cut short in youth, and retrimmed in old age, the outfit made but a sorry figure going up the street. The Professor said it suggested the idea of some fossil vertabra, with a paint brush attached to its end, running away with a geological student.

After the return and cries for more bids, Muggs must have winked at the auctioneer—possibly, to slyly telegraph him the fact that in "Hengland" they were up to such games. At least the auctioneer so declared, and advancing the price one dollar in accordance therewith, finally knocked the brute down to him. Then the British wrath bubbled and boiled. The auctioneer was inexorable. Muggs had winked, and that was an advanced bid, according to commercial custom the land over. Articles were often sold simply by the vibration of an eyelash, and not a word uttered.

The Professor remarked that in law winks would doubtless be accepted as evidence. It was a recognized principle of the statutes that he who winked at a matter acquiesced in it, and indeed such signals were often more expressive than words. Sachem sustained this point, and added further that he had known many a man's head broken on account of an injudicious wink.

The crowd, with almost unanimous voice, pronounced the auctioneer right and Muggs wrong.

"Me take the brute!" exclaimed the indignant Briton; "why he can 'ardly stand up long enough to be knocked down. Except in France, he could be put to no earthly use whatever. 'Is knees knock together in an ague quartette, and 'is tail—look at it! It's hincapable of knocking a fly off; looks more like flying off hitself!" Muggs further declared the sale was an attempt on the owner's part to evade the health officer, who would have been around, in a couple of days, to have the carcass removed.

The auctioneer waxed belligerent, the crowd noisy, and Muggs, like a true Englishman, secured peace at the price of British gold. The horse was on his hands, having barely escaped being on the town, and an enthusiastic crowd of urchins escorted the purchase to a livery stable. Muggs christened the animal Cynocephalus, and soon afterward sold him to Mr. Colon, who was of an economical turn, for the use of his son Semi.

"I have heard," said the thoughtful father, "that the buffalo grass of the plains is very nourishing. All that the poor steed needs is care and fat pastures. Semi can give him the former, and over the latter our future journey lies. I have also learned that what is especially needed in a hunting horse is steadiness, and this quality the animal certainly possesses."

From some months' acquaintance with the purchase, we can say that Cynocephalus was steady to a remarkable degree. We are firmly persuaded that a heavy battery might have fired a salute over his back without moving him, unless, possibly, the concussion knocked him down.

Our first hunting morning, the second day preceding our hegira westward, came to us with a clear sky, the sun shedding a mellow warmth, and the air full of those exhilarating qualities which our lungs afterward drank in so freely on the plains. Indian summer, delightful anywhere, is especially so in Kansas.

From the advance guard of the winter king not a single chilling zephyr steals forward among the tarrying ones of summer. Soothing and gentle as when laden with spicy fragrance south, they here shower the whole land with sunbeams. Earth no longer seems a heavy, inert mass, but floats in that smoky, fleecy atmosphere with which artists delight so much to wrap their angels. It is as if the warmer, lighter clouds of sunny weather were nestling close to earth, frightened from the skies, like a flock of white swans, at the October howls of winter. But I never could agree with those writers who call this season dreamy. If such it be, it is surely a dream of motion. All nature appears quickened. The inhabitants of the air have commenced their southern pilgrimage, and the oldest and leading ganders may be heard croaking, day-time and night-time, to their wedge-shaped flocks their narrative of summer experiences at the Arctic circle, and their commands for the present journey.

Sachem, I find, has recorded as a discovery in natural history that geese form their flocks in wedge shape that they may easier "make a split" for the south when Nature, with her north pole, stirs up their feeding and breeding-grounds in November gales, and changes their fields of operation into fields of ice. Sachem was sadly addicted to slang phrases.

All game, I may remark, is wilder at this season of the year than earlier. If the earth is dreaming, its wild inhabitants certainly are not. Men, too, have thrown off the summer lethargy, and shave their neighbors as closely as ever. If any one thinks it a dreamy season of the year, let him test the matter practically by being a day or two behindhand with a payment.

In reply to a question, the professor told us that the smoky condition of the atmosphere was probably caused by the exhalation of phosphorus from decaying vegetation. Sachem remarked that out of twenty different objects which he had submitted for examination, and as many questions that he had asked, nine-tenths of the results contained phosphorus in some shape. It was becoming monotonous and dangerous.

While the party thus mused and speculated, we had come out into the open country, south-west of town, and were now approaching Webster's Mound, a cone-shaped hill from which we afterward obtained some excellent views. For the trip we had been supplied with two dogs, one a setter, belonging to the private secretary of the Governor, and the other a pointer, the property of a real estate dealer. The former was an ancient and venerable animal. The rheumatism was seized of his backbone and held high revel upon the juices which should have lubricated the joints. Even his tail wagged with a jerk, inclining the body to whichever side it had last swung. He was so full of rheumatism that whenever he scented a chicken the pain evoked by the excitement caused him to howl with anguish. The pointer, per contra, was hale and swift, but had lost one eye; and a shot from the same charge which destroyed that organ, rattled also on his left ear-drum, and that membrane no longer responded to the shouts of the hunter. On one side he could see, and not hear—on the other, hear, but not see. Nevertheless, with gestures for the left view, and shouts on the right, fair work might still be obtained. Both dogs rejoiced in the uncommon name of Rover, and both possessed that most excellent of all points in such animals, a steady point.

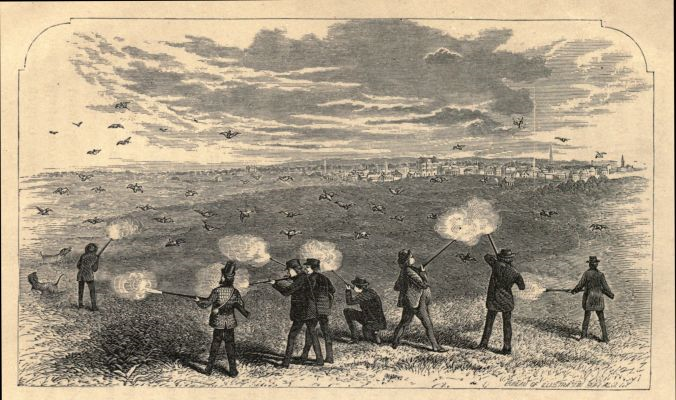

If any of my readers are fond of field-sports, and have not yet shot prairie-chickens over a dog, let them take their guns and hie to the West, and taste for themselves of this rare sport. With the wide prairie around him, keeping the bird in full view during its passage through the air, one can choose his distance for firing and witness the full effect of his shot. I think the brief instant when the flight of the bird is checked and it drops head-foremost to earth, is the sweetest moment of all to the hunter.

CHAPTER IV

CHICKEN-SHOOTING CONTINUED—A SCIENTIFIC PARTY TAKE THE BIRDS ON THE WING—EVILS OF FAST FIRING—AN OLD-FASHIONED "SLOW SHOT"—THE HABITS OF THE PRAIRIE-CHICKEN—ITS PROSPECTIVE EXTINCTION—MODE OF HUNTING IT—THE GOPHER SCALP LAW.

We had left the road and were now driving over the fine prairie skirting Webster's Mound, the grass being about a foot high and affording excellent cover. Taking advantage of its being matted so closely from the early frosts, the old cocks hid under the thick tufts and called for close work on the part of our dogs.

Back and forth across our path these intelligent animals ranged, the one fifty yards or so to our right, the other as many to our left, crossing and re-crossing, with open mouths drinking in eagerly the tainted breeze. This latter was in our favor, and both dogs suddenly joined company and worked up into it, with outstretched noses pointing to game that was evidently close ahead.

The pointer crawled cautiously, like a tiger, his spotted belly sweeping the earth, and his tail, which had been lashing rapidly an instant before, gradually stiffening. He would open his mouth suddenly, drink in a quick, deep draught of air, and, closing the jaws again, hold it until obliged to take another respiration. He seemed as loath to let the scent of the chicken pass from his nostrils as a hungry newsboy is to quit the savory precincts of Delmonico's kitchen window. The setter's old bones appeared to renew their youth under the excitement, and he was as active as a retired war-horse suddenly plunged into battle.

Both dogs came simultaneously to a point—tails curved up and rigid, each body motionless as if cut in marble and one forepaw lifted. No wonder so many men are wild with a passion for hunting. Kind Providence smiles upon the legitimate sport from conception to close, and gives us a posé to start with fascinating to any lover of the beautiful, whether hunter or not. But one must not pause to moralize while dogs are on the point, or he will have more philosophy than chickens.

All the party had got safely to ground and were behind the dogs, with guns ready and eyes eagerly fastened on the thick grass which concealed its treasure as completely as if it had been a thousand miles below its roots, or on the opposite side of this mundane sphere in China. Not a thing was visible within fifty yards of our noses save two dogs standing motionless, with stiffened tails and eyes fixed on, and nozzles pointed toward, a spot in the sea of brown, withered grass, not ten feet away.

The Professor took out his lens, Mr. Colon let down the hammers of his gun and cocked them again, to be sure all was right, while Sachem wore a puzzled expression as if undecided whether the attitude of the dogs indicated any thing particular or not. The grass nodded and rustled in the light wind, but not a blade moved to indicate the presence of any living thing beneath it, while the dogs remained as if petrified.

The Professor said it was very remarkable, and wondered what had better be done next. Mr. Colon thought that the dogs were tired, and we might as well get into the wagon. Another suggested at random that we should set the dogs on, and Muggs, who had probably heard the expression somewhere, cried, "Hi, boys, on bloods!" At the words the dogs made a few quick steps forward, and on the instant the grass seemed alive with feathered forms, popping into air like bobs in shuttlecock. Such a fluttering and flying I have never seen since, when a boy, I ventured into a dove cote, and was knocked over by the rush of the alarmed inmates. From under our very feet, almost brushing our faces, the beautiful pinnated grouse of the prairies left their cover, and us also.

Every gun had gone off on the instant, and we doubt if one was raised an inch higher than it happened to be when the covey started. The Professor afterward extracted some stray shot from the legs of his boots, and the setter, which was next to Muggs, gave a cry of pain for which there was evidently other cause than rheumatism, as was demonstrated by his retirement to the rear, from which he refused to budge until we all got into the wagon, and to which he invariably retreated whenever we got out.

OUR FIRST BIRD-SHOOTING.

From the midst of the birds which were soaring away, one was seen to rise suddenly a few feet above his comrades, and then fall straight as a plummet, and head first, to earth. It had caught some stray shot from the bombardment—Muggs claimed from his gun, but this statement the setter, could he have spoken, would certainly have disputed.

Semi-Colon brought in the game, which proved to be a fine male, with whiskers and full plumage, which must have made sad havoc among the hearts of the hens, when the old fellow was on annual dress parade in the spring. At that season of the year the cocks seek some knoll of the prairie, where the grass has been burnt or cut off, and strut up and down with ruffled feathers, uttering meanwhile a booming sound, which can be heard in a clear morning for miles. The flabby pink skin that at other seasons hangs in loose folds on his neck is then distended like a bagpipe, and he is a very different bird from the same individual in his Quaker gray and respectable summer and fall habits.