Полная версия

Полная версияVegetable Diet: As Sanctioned by Medical Men, and by Experience in All Ages

"Another objection, still, against a milk and vegetable diet is, that it breeds phlegm, and so is unfit for tender persons, of cold constitutions; especially those whose predominant failing is too much phlegm. But this objection has as little foundation as either of the preceding. Phlegm is nothing but superfluous chyle and nourishment, as the taking down more food than the expenses of living and the waste of the solids and fluids require. The people that live most on such foods – the eastern and southern people and those of the northern I have mentioned – are less troubled with phlegm than any others. Superfluity will always produce redundancy, whether it be of phlegm or choler; and that which will digest the most readily, will produce the least phlegm – such as milk, seeds, and vegetables. By cooling and relaxing the solids, the phlegm will be more readily thrown up and discharged – more, I say, by such a diet than by a hot, high, caustic, and restringent one; but that discharge is a benefit to the constitution, and will help it the sooner and faster to become purified, and so to get into perfect good health. Whereas, by shutting them up, the can or cask must fly and burst so much the sooner.

"The only material and solid objections against a milk, seed, and vegetable diet, are the following:

"First, That it is particular and unsocial, in a country where the common diet is of another nature. But I am sure sickness, lowness, and oppression, are much more so. These difficulties, after all, happen only at first, while the cure is about; for, when good health comes, all these oddnesses and specialities will vanish, and then all the contrary to these will be the case.

"Secondly, That it is weakening, and gives a man less strength and force, than common diet. It is true that this may be the result, at first, while the cure is imperfect. But then the greater activity and gayety which will ensue on the return of health, under a milk and vegetable diet, will liberally supply that defect.

"Thirdly, The most material objection against such a diet is, that it cools, relaxes, softens, and unbends the solids, at first, faster than it corrects and sweetens the juices, and brings on greater degrees of lowness than it is designed to cure; and so sinks, instead of raising. But this objection is not universally true; for there are many I have treated, who, without any such inconvenience, or consequent lowness, have gone into this regimen, and have been free from any oppression, sinking, or any degree of weakness, ever after; and they were not only those who have been generally temperate and clean, free from humors and sharpnesses, but who, on the decline of life, or from a naturally weak constitution or frame, have been oppressed and sunk from their weakness and their incapacity to digest common animal food and fermented liquors.

"I very much question if any diet, either hot or cool, has any great influence on the solids, after the fluids have been entirely sweetened and balmified. Sweeten and thin the juices, and the rest will follow, as a matter of course."

At page 90 of Dr. Cheyne's Natural Method of Curing Diseases, he thus says:

"People think they cannot possibly subsist on a little meat, milk, and vegetables, or on any low diet, and that they must infallibly perish if they should be confined to water only; not considering that nine tenths of the whole mass of mankind are necessarily confined to this diet, or pretty nearly to it, and yet live with the use of their senses, limbs, and faculties, without diseases, or but few, and those from accidents or epidemical causes; and that there have been nations, and now are numbers of tribes, who voluntarily confine themselves to vegetables only; as the Essenes among the Jews, some Hermits and Solitaries among the Christians of the first ages, a great number of monks in the Chartreux now in Europe, Banians among the Indians and Chinese, the Guebres among the Persians, and of old, the Druids among ourselves."

To illustrate the foregoing, I may here introduce the following extracts from the sixth London edition of Dr. Cheyne's Essay on Health and Long Life.

"It is surprising to what a great age the Eastern Christians, who retired from the persecutions into the deserts of Egypt and Arabia, lived healthful on a very little food. We are informed, by Cassian, that the common measure for twenty-four hours was about twelve ounces, with only pure water for drink. St. Anthony lived to one hundred and five years on mere bread and water, adding only a few herbs at last. On a similar diet, James the Hermit lived to one hundred and four years. Arsenius, the tutor of the emperor Arcadius, to one hundred and twenty – sixty-five years in society, and fifty-five in the desert. St. Epiphanius, to one hundred and fifteen; St. Jerome, about one hundred; Simon Stylites, to one hundred and nine; and Romualdus, to one hundred and twenty.

"It is wonderful in what sprightliness, strength, activity, and freedom of spirits, a low diet, even here in England, will preserve those who have habituated themselves to it. Buchanan informs us of one Laurence, who preserved himself to one hundred and forty, by the mere force of temperance and labor. Spotswood mentions one Kentigern (afterward called St. Mongah, or Mungo, from whom the famous well in Wales is named), who lived to one hundred and eighty-five years; and who, after he came to years of understanding, never tasted wine or strong drink, and slept on the cold ground.

"My worthy friend, Mr. Webb, is still alive. He, by the quickness of the faculties of the mind, and the activity of the organs of his body, shows the great benefit of a low diet – living altogether on vegetable food and pure water. Henry Jenkins lived to one hundred and sixty-nine years on a low, coarse, and simple diet. Thomas Parr died at the age of one hundred and fifty-two years and nine months. His diet was coarse bread, milk, cheese, whey, and small beer; and his historian tells us, that he might have lived a good while longer if he had not changed his diet and air; coming out of a clear, thin air, into the thick air of London, and being taken into a splendid family, where he fed high, and drank plentifully of the best wines, and, as a necessary consequence, died in a short time. Dr. Lister mentions eight persons in the north of England, the youngest of whom was above one hundred years old, and the oldest was one hundred and forty. He says, it is to be observed that the food of all this mountainous country is exceeding coarse."

Dr. C., in his Natural Method, at page 91, thus continues his remarks:

"And there are whole villages in this kingdom, even of those who live on the plains, who scarce eat animal food, or drink fermented liquors a dozen times a year. It is true, most of these cannot be said to live at ease and commodiously, and many may be said to live in barbarity and ignorance. All I would infer from this is, that they do live, and enjoy life, health, and outward serenity, with few or no bodily diseases but from accidents and epidemical causes; and that, being reduced by voluntary and necessary poverty, they are not able to manage with care and caution the rest of the non-naturals, which, for perfect health and cheerfulness, must all be equally attended to, and prudently conducted; and their ignorance and brutality is owing to the want of the convenience of due and sufficient culture and education in their youth.

"But the only conclusion I would draw from these historical facts is, that a low diet, or living on vegetables, will not destroy life or health, or cause nervous and cephalic distempers; but, on the contrary, cure them, as far as they are curable. I pretend to demonstrate from these facts, that abstinence and a low diet is the great antidote and universal remedy of distempers acquired by excess, intemperance, and a mistaken regimen of high meats and drinks; and that it will greatly alleviate and render tolerable the original distempers derived from diseased parents; and that it is absolutely necessary for the deep thinking part of mankind, who would preserve their faculties sound and entire, ripe and pregnant to a green old age and to the last dregs of life; and that it is, lastly, the true and real antidote and preservative from heavy-headedness, irregular and disorderly intellectual functions, from loss of the rational faculties, memory, and senses, and from all nervous distempers, as far as the ends of Providence and the condition of mortality will allow.

"Let two people be taken as nearly alike as the diversity and the individuality of nature will admit, of the same age, stature, complexion, and strength of body, and under the same chronical distemper, and I am willing to take the seeming worse of the two; let all the most promising nostrums, drops, drugs, and medicines known among the learned and experienced physicians, ancient or modern, regular physicians or quacks, be administered to the best of the two, by any professor at home or abroad; I will manage my patient with only a few naturally indicated and proper evacuations and sweetening innocent alternatives, which shall neither be loathsome, various, nor complicated, require no confinement, under an appropriate diet, or, in a word, under the 'lightest and the least,' or at worst under a milk and seed diet; and I will venture reputation and life, that my method cures sooner, more perfectly and durably, is much more easily and pleasantly passed through, in a shorter time, and with less danger of a relapse than the other, with all the assistance of the best skill and experience, under a full and free, though even a commonly reputed moderate diet, but of rich foods and generous liquors; much more, under a voluptuous diet."

But I am unwilling to dismiss this subject without inserting a few more extracts from Dr. Cheyne, to show his views of the treatment of diseases. And first, of the scurvy, and other diseases which he supposes to arise from it.

"There is no chronical distemper, whatsoever, more universal, more obstinate, and more fatal in Britain than the scurvy, taken in its general extent. Scarce any one chronical distemper but owes its origin to a scorbutic tendency, or is so complicated with it, that it furnishes the most cruel and most obstinate symptoms. To it we owe all the dropsies that happen after the meridian of life; all diabetes, asthmas, consumptions of several kinds; many sorts of colics and diarrhœas; some kinds of gouts and rheumatisms, all palsies, various kinds of ulcers, and possibly the cancer itself; and most cutaneous foulnesses, weakly constitutions, and bad digestions; vapors, melancholy, and almost all nervous distempers whatsoever. And what a plentiful source of miseries the last are, the afflicted best can tell. And scarce any one chronical distemper whatever, but has some degree of this evil faithfully attending it. The reason why the scurvy is peculiar to this country and so fruitful of miseries, is, that it is produced by causes mostly special and particular to this island, to wit: the indulging so much in animal food and strong fermented liquors, sedentary and confined employments, etc.

"Though the inhabitants of Britain live, for the most part, as long as those of a warmer climate, and probably rather longer, yet scarce any one, especially those of the better sort, but becomes crazy and suffers under some chronical distemper or other, before he arrives at old age.

"Nothing less than a very moderate use of animal food, and that of the least exciting kind, and a more moderate use of spirituous liquors, due exercise, etc., can keep this hydra under. And nothing else than a total abstinence from animal food and alcoholic liquors can totally extirpate it."

The following are extracted from his "Natural Methods." I do not lay them down as recipes, to be followed in the treatment of diseases; but to show the views of Dr. Cheyne in regard to vegetable regimen.

"1. Cancer.– Any cancer that can be cut out, contracted, and healed up with common, that is, soft, cool, and gently astringent dressings, and at last left as an issue on the part, may, by a cow's milk and seed diet continued ever afterward, be made as easy to the patient, and his life and health as long preserved, almost, as if he had never been afflicted with it; especially if under fifty years of age.

"2. Cancer.– A total ass's milk diet – about two quarts a day, without any other meat or drink – will in time cure a cancer in any part of the body, with mere common dressings, provided the patient is not quite worn out with it before it is begun, or too far gone in the common duration of life and even in that case, it will lessen the pain, lengthen life, and make death easier, especially if joined with small interspersed bleedings, millepedes, crabs' eyes prepared, nitre and rhubarb, properly managed. But the diet, even after the cure, must be continued, and never after greatly altered, unless it be into cow's milk with seeds.

"3. Consumption.– A total milk and seed diet, gentle and frequent bleedings, as symptoms exasperate, a little ipecacuanha or thumb vomit repeated once or twice a week, chewing quill bark in the morning, and a few grains of rhubarb at night, will totally cure consumptions, even when attended with tubercles, and hemoptoe, and hectic, in the first stage; will greatly relieve, if not cure, in the second stage, especially if riding and a warm clear air be joined; and make death easier in the third and last stage.

"4. Fits.– A total cow's milk diet – about two quarts a day – without any other food, will at last totally cure all kinds of fits, epileptical, hysterical, or apoplectic, if entered upon before fifty. But the patient, if near fifty, must ever after continue in the same diet, with the addition only of seeds; otherwise his fits will return oftener and more severely, and at last cut him off.

"5. Palsy.– A total cow's milk diet, without any other food, will bid fairest to cure a hemiplegia or even a dead palsy, and consequently all the lesser degrees of a partial one, if entered upon before fifty. And this distemper I take to be the most obstinate, intractable, and disheartening one that can afflict the human machine; and is chiefly produced by intemperate cookery, with its necessary attendant, habitual luxury.

"6. Gout.– A total milk and seed diet, with gentle vomits before and after the fits, chewing bark in the morning and rhubarb at night, with bleeding about the equinoxes, will perfectly cure the gout in persons under fifty, and greatly relieve those farther advanced in life; but must be continued ever after, if such desire to get well.

"7. Gravel.– Soap lees, softened with a little oil of sweet almonds, drunk about a quarter of an ounce twice a day on a fasting stomach; or soap and egg-shell pills, with a total milk and seed diet, and Bristol water beverage, will either totally dissolve the stone in kidneys or bladder, or render it almost as easy as the nail on one's finger, if the patient is under fifty, and much relieve him, even after that age.

"In about thirty years' practice, in which I have, in some degree or other, advised this method in proper cases, I have had but two patients in whose total recovery I have been mistaken, and these were both scrofulous cases, where the glands and tubercles were so many, so hard, and so impervious that even the ponderous remedies and diet joined could not discuss them; and they were both also too far gone before they entered upon them; – and I have found deep scrofulous vapors the most obstinate of any of this tribe of these distempers. And indeed nothing can possibly reach such, but the ponderous medicines, joined with a liquid, cool, soft, milk and seed regimen; and if these two do not, in due time, I can boldly affirm it, nothing ever will."

Dr. Cheyne goes on to speak of the cure, on similar principles, of a great many other difficult or dangerous diseases, as asthma, pleurisy, hemorrhage, mania, jaundice, bilious colic, rheumatism, scurvy, and venereal disease; but he modestly owns that, in his opinion on these, he does not feel such entire confidence as in the former cases, for want of sufficient experiments. He, however, closes one of his chapters with the following pretty strong statement:

"I am morally certain, and am myself entirely convinced, that a milk and seed, or milk and turnip diet, duly persisted in, with the occasional helps mentioned (elsewhere) on exacerbations, will either totally cure or greatly relieve every chronical distemper I ever saw or read of."

Another chapter is thus concluded, and with it I shall conclude my extracts from his writings.

"Some, perhaps, may controvert, nay, ridicule the doctrine laid down in these propositions. I shall neither reply to, nor be moved with any thing that shall be said against them. If they are of nature and truth, they will stand; if not, I consent they should come to nought. I have satisfied my own conscience – the rest belongs to Providence. Possibly time and bodily sufferings may justify them; – if not to this generation, perhaps to some succeeding one. I myself am convinced, by long and many repeated experience, of their justness and solidity. If what has been advocated through this whole treatise does not convince others, nothing I can add will be sufficient. I will leave only this reflection with my readers.

"All physicians, ancient and modern, allow that a milk and seed diet will totally cure before fifty, and infinitely alleviate after it, the consumption, the rheumatism, the scurvy, the gout – these highest, most mortal, most painful, and most obstinate distempers; and nothing is more certain in mathematics, than that which will cure the greater will certainly cure the lesser distempers."

DR. GEOFFROYDr. Geoffroy, a distinguished French physician and professor of chemistry and medicine in some of the institutions of France, flourished more than a hundred years ago. The bearing of the following extract will be readily seen. It is from the Memoirs of the Royal Academy for the year 1730; and I am indebted for it to the labors of Dr. Cheyne.

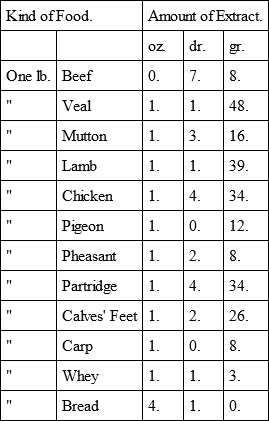

"M. Geoffroy has given a method for determining the proportion of nourishment or true matter of the flesh and blood, contained in any sort of food. He took a pound of meat that had been freed from the fat, bones, and cartilages, and boiled it for a determined time in a close vessel, with three pints of water; then, pouring off the liquor, he added the same quantity of water, boiling it again for the same time; and this operation he repeated several times, so that the last liquor appeared, both in smell and taste, to be little different from common water. Then, putting all the liquor together, and filtrating, to separate the too gross particles, he evaporated it over a slow fire, till it was brought to an extract of a pretty moderate consistence.

"This experiment was made upon several sorts of food, the result of which may be seen in the following table. The weights are in ounces, drachms, and grains; sixty grains to a drachm, and eight drachms to an ounce.

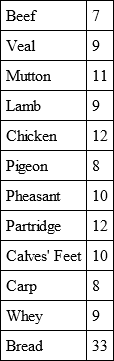

"The relative proportion of the nourishment will be as follows:

"From the foregoing decisive experiments it is evident that white, young, tender animal food, bread, milk, and vegetables are the best and most effectual substances for nutrition, accretion, and sweetening bad juices. They may not give so strong and durable mechanical force, because being easily and readily digestible, and quickly passing all the animal functions, so as to turn into good blood and muscular flesh, they are more transitory, fugitive, and of prompt secretion; yet they will perform all the animal functions more readily and pleasantly, with fewer resistances and less labor, and leave the party to exercise the rational and intellectual operations with pleasure and facility. They will leave Nature to its own original powers, prevent and cure diseases, and lengthen out life."

Now if this experiment proves what Dr. C. supposes in favor of the lighter meats and vegetables taken together, how much more does it prove for bread alone? For it cannot escape the eye of the least observing that this article, though placed last in the list of Dr. Geoffroy, is by far the highest in point of nutriment; nay, that it is about three times as high as any of the rest. I am not disposed to lay so much stress on these experiments as Dr. C. does; nevertheless, they prove something Connected with the more recent experiments of Messrs. Percy and Vauquelin and others, how strikingly do they establish one fact, at least, viz., that bread and the other farinaceous vegetables cannot possibly be wanting in nutriment; and how completely do they annihilate the old-fashioned doctrine – one which is still abroad and very extensively believed – that animal food is a great deal more nourishing than vegetable! No careful inquirer can doubt that bread, peas, beans, rice, etc., are twice as nutritious – to say the least – as flesh or fish.

MESSRS. PERCY AND VAUQUELINAs I have alluded, in the preceding article, to the experiments of Messrs. Percy and Vauquelin, two distinguished French chemists, their testimony in this place seems almost indispensable, even though we should not regard it, in the most strict import of the term, as medical testimony. The result of their experiments, as communicated by them to the French minister of the interior, is as follows:

In bread, every one hundred pounds is found to contain eighty pounds of nutritious matter; butcher's meat, averaging the different sorts, contains only thirty-five pounds in one hundred; French beans (in the grain), ninety-two pounds in one hundred; broad beans, eighty-nine pounds; peas, ninety-three pounds; lentils (a species of half pea little known with us), fifty-four pounds in one hundred; greens and turnips only eight pounds of solid nutritious substance in one hundred; carrots, fourteen pounds; and one hundred pounds of potatoes yield only twenty-five pounds of nutriment.

I will just affix to the foregoing one more table. It is inserted in several other works which I have published; but for the benefit of those who may never yet have seen it, and to show how strikingly it corresponds with the results of the experiments of Geoffroy, Percy, and Vauquelin, I deem it proper to insert it.

Of the best wheat, one hundred pounds contain about eighty-five pounds of nutritious matter; of rice, ninety pounds; of rye, eighty; of barley, eighty-three; of beans, eighty-nine to ninety-two; peas, ninety-three; lentils, ninety-four; meat (average), thirty-five; potatoes, twenty-five; beets, fourteen; carrots, ten; cabbage, seven; greens, six; and turnips, four.

DR. PEMBERTONDr. Pemberton, after speaking of the general tendency, in our highly fed communities, to scrofula and consumption, makes the following remarks, which need no comment:

"If a child is born of scrofulous parents, I would strongly recommend that it be entirely nourished from the breast of a healthy nurse, for at least a year. After this, the food should consist of milk and farinaceous vegetables. By a perseverance in this diet for three years, I have imagined that the threatened scrofulous appearances have certainly been postponed, if not altogether prevented."

SIR JOHN SINCLAIRSir John Sinclair, an eminent British surgeon, says, "I have wandered a good deal about the world, my health has been tried in all ways, and, by the aid of temperance and hard work, I have worn out two armies in two wars, and probably could wear out another before my period of old age arrives. I eat no animal food, drink no wine or malt liquor, or spirits of any kind; I wear no flannel; and neither regard wind nor rain, heat nor cold, when business is in the way."

DR. JAMES, OF WISCONSINDr. James, of Wisconsin, but formerly of Albany, and editor of a temperance paper in that city, one of the most sensible, intelligent, and refined of men, and one of the first in his profession, is a vegetable eater, and a man of great simplicity in all his physical, intellectual, and moral habits. I do not know that his views have ever been presented to the public, but I state them with much confidence, from a source in which I place the most implicit reliance.