Полная версия

Полная версияVegetable Diet: As Sanctioned by Medical Men, and by Experience in All Ages

"Position IV. – With about equal potency alcohol and flesh meats weaken the force of the capillaries of the system, on which healthy action so much depends.

"Position V. – A flesh diet, in common with the use of strong drink, impairs the tone of the nutritive apparatus, by which its ability to work up raw material and manufacture it into sound, well finished vital fabric, is diminished, and of course the appetite or call for food is satisfied with a less quantity of the raw material. This fact has given rise to the opinion that animal food contains more nutriment than vegetable.

"Position VI. – The total abandonment of an habitual use of animal food is attended with all the perplexing, uncomfortable, and distressing difficulties that follow the giving up of an habitual use of strong drink. A change from one kind of simple nutriment to another has no such effect. It is only when the constant use of some stimulating substance is abandoned that such difficulties are experienced."

DR. JARVISThis gentleman, in his "Practical Physiology," at page 86, has the following thoughts:

"Some have contended that man was designed to eat only of the fruits and vegetables of the earth; while others maintain, with equal confidence, that he should add to these the flesh of beasts. There are many individuals, both in this and other countries, who confine themselves to vegetable diet. They believe they enjoy better health, and maintain greater strength of body and mind, than those who live on a mixed diet. The experiment has not been tried on a sufficiently extensive range to determine its value. It has not proved a failure, nor has it demonstrated, to the satisfaction of all, that flesh is injurious."14

DR. TICKNOR"From the fact," says this author, "that animal food is proper and necessary for health in polar regions, and that a vegetable diet is equally proper and necessary in the torrid zone, we may conclude that in winter, in our own climate, an animal diet is the best; while vegetables are more conducive to health in the summer season."

It would not be difficult to prove, from the very concessions of Dr. T., that vegetable food is better adapted to health, in general, than animal; but I forbear to do so, in this place. The subject will be fully discussed in the concluding chapter.

DR. COLESThe author of a small volume recently published at Boston, entitled the "Philosophy of Health; or, Health without Medicine," is more decided in his views on diet than any late writer I have seen, except Dr. Jennings and O. S. Fowler. He says, at page 35:

"Man, in his original, holy state, was provided for from the vegetables of that happy garden which was given him to prune. This was the Creator's original plan; * * * * the eating of flesh was one of the consequences of the fall. Living on vegetable food is undoubtedly the most natural and healthy method of subsistence."

Again, at page 45 – "The objections, then, against meat-eating are threefold – intellectual, moral, and physical. Its tendency is to check intellectual activity, to depreciate moral sentiment, and to derange the fluids of the body."

DR. SHEWThis active physician is zealously devoted to the propagation of hydropathy. He uses no medicine in the management of disease – nothing at all but water. To this, however, he adds great attention to diet. In his Journal,15 and elsewhere, he is a zealous and able advocate of the vegetable system, preferring it himself, and recommending it to his patients and followers.

Dr. Shew's opinion, in this particular, is entitled to the more weight from the fact of his having been very familiar with disease and diet, both in the old world and the new. He has been twice to Germany; and has spent much time at Graefenberg, with Priessnitz, the founder of the system which he so zealously defends and practices, and so strongly advocates.

DR. MORRILLDr. C. Morrill, in a recent work entitled, "Physiology of Woman, and her Diseases," says much in favor of an exclusively vegetable diet in some of the diseases of woman; and among other things, makes the following general remarks:

"Even by those who labor (referring here to the healthy), meat should be taken moderately, and but once a day. The sedentary, generally, do not need it."

DR. BELLThis gentleman's testimony has been given elsewhere. I only subjoin the following: "By far the greater number of the inhabitants of the earth have used, in all ages, and continue to use, at this time, vegetable aliment alone."

DR. BRADLEYDr. D. B. Bradley, the distinguished missionary at Bangkok, in Siam, though not exactly a vegetable eater, is favorably disposed to the vegetable system. He has read Graham and myself with great care, and is an anxious inquirer after all truth.

DR. STEPHENSONDr. Chauncy Stephenson, of Chesterfield, Massachusetts, in what he calls his "New System of Medicine," commends to all his readers, for their sustenance, "pure air, a proper temperature, good vegetable food, and pure cold water." And lest he should be misunderstood, he immediately adds – "The best articles of food for general use are good, well-baked cold bread, made of rye and Indian corn, wheat or barley meal; rice, good ripe fruits of all kinds, both fresh and dried, and a proper proportion of good roots, such as potatoes, parsneps, turnips, onions, etc." Even milk he regards as a questionable food for adults or middle aged persons.

Again, he says: "Animal food, in general, digests sooner than most kinds of vegetables; and not being so much in accordance with man's nature, constitution, and moral character, it is very liable, finally, to generate disease, inflammation, or fever, even when it is not taken to excess." He closes by advising all persons to content themselves with "pure vegetable food;" and that in the least quantity compatible with good health.

DR. J. BURDELL,A distinguished dentist of New York, has long been a vegetable eater, and a zealous defender of the faith (in this particular) which he professes.

DR. THOMAS SMETHURST,In a work entitled Hydrotherapia, says, "Children thrive best upon a simple, moderately nourishing vegetable diet." And if children thus thrive the best, why not adults?

DR. SCHLEMMERDr. C. V. Schlemmer, a German by birth, but now an adopted son of old England, in giving an account of the diet of himself, his three sons of eleven, ten, and four years of age, with their tutor, observes: "Raw peas, beans, and fruit are our food: our teeth are our mills; the stomach is the kitchen." And all of them, as he affirms, enjoy the best of health. For himself, as he says, he has practiced in this way six years.

DR. CURTIS, AND OTHERSDr. Curtis, a distinguished botanic physician of Ohio, with several other physicians, both of the old and the new school, whom I have not named, do not hesitate to regard a pure vegetable diet, in the abstract, as by far the best for all mankind, both in health and disease.

Dr. Porter, of Waltham, for example, when I meet him, always concedes that a well-selected vegetable diet is superior to every other. He has repeatedly told me of an experiment he made, of three months, on mere bread and water. Never, says he, was I more vigorous in body and mind, than at the end of this experiment. But the reader well knows that I am not an advocate of a diet of mere bread and water. I regard fruits, or fruit juices – unfermented – almost as necessary, to adults, as bread.

PROF. C. U. SHEPARDThe reputation of this gentleman, in the scientific world, is so well known, that no apology can be necessary for inserting his testimony. As a chemist, he is second to very few, if any, men in this country. The following are his remarks:

"Start not back at the idea of subsisting upon the potato alone, ye who think it necessary to load your tables with all the dainty viands of the market – with fish, flesh, and fowl, seasoned with oil and spices, and eaten, perhaps, with wines; – start not back, I say, with disgust, until you are able to display in your own pampered persons a firmer muscle, a more beau-ideal outline, and a healthier red than the potato-fed peasantry of Ireland and Scotland once showed you, as you passed by their cabin doors!

"No; the chemical physiologist will tell you that the well ripened potato, when properly cooked, contains every element that man requires for nutrition; and in the best proportion in which they are found in any plant whatever. There is the abounding supply of starch for enabling him to maintain the process of breathing, and for generating the necessary warmth of body; there is the nitrogen for contributing to the growth and renovation of organs; the lime and phosphorus for the bones; and all the salts which a healthy circulation demands. In fine, the potato may well be called the universal plant."

BLACKWOOD, IN HIS MAGAZINE"Chemistry," says Blackwood's Magazine, "has already told us many remarkable things in regard to the vegetable food we eat – that it contains, for example, a certain per centage of the actual fat and lean we consume in our beef, or mutton, or pork – and, therefore, that he who lives on vegetable food may be as strong as the man who lives on animal food, because both in reality feed on the same things, in a somewhat different form."

There is this difference, however, that in the one case – that is, in the use of the vegetables which contain the elements referred to – we save the trouble of running it through the body of the living animal, and losing seven eighths of it, as we do, practically in the process; whereas in the other we do not. We also save ourselves the necessity of training the young and the old to scenes of butchery and blood.

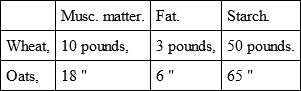

PROF. JOHNSTONThis gentleman, in a recent edition of his "Elements of Agricultural Chemistry and Geology," tells us that from experiments made in the laboratory of the Agricultural Association of Scotland, wheat and oats, when analyzed, contain of nutritious properties the following proportion:

Thus oats, and even wheat, are quite rich in that which forms muscular matter in the human body.

SIMEON COLLINS, OF WESTFIELD, MASSThis gentleman, in his fifty-first year, states that having been for several years afflicted with a severe cough, which he supposed bordered upon consumption, he "discontinued the use of flesh meat, fish, fowl, butter, gravy, tea, and coffee, and made use of a plain vegetable diet." "My bread," says he, "is made of unbolted wheat meal; my drink is pure cold water; my bed, for winter and summer, is made of the everlasting flower; and my health is, and ever has been, perfect, since I got fairly cleansed from the filthiness of flesh meat, and other pernicious articles of diet in common use.

"My business requires a great degree of activity, and I can truly say that I am a stranger to weariness or languor. At the time of entering upon this system, I had a wife and five children, the youngest eight years of age; – they all soon entered upon the same course of living with myself, and soon were all benefited in health. I have now six children – the youngest fifteen months old, and as happy as a lark. Previous to the time of our adopting the present system of living, my expenses for medicine and physicians would range from $20 to $30 a year – for the last four years it has been nothing worth naming."

REV. JOSEPH EMERSONMr. Emerson was a teacher of eminence, known throughout the United States, but particularly so in Massachusetts and Connecticut. He died in the latter state, in 1833, aged about fifty-five. He had long been a miserable dyspeptic, but was probably kept alive amid certain strange violations of physical law, such as studying hard till midnight, for example, for many years, by his great care in regard to his diet. Mrs. Banister, late Miss Z. P. Grant (the associate, at Ipswich, of Miss Lyon, who died recently at South Hadley, who was his pupil), thus speaks of his rigid habits:

"He not only uniformly rejected whatever food he had decided to be injurious to him, but whatever he deemed necessary for his food or drink, was always taken, whether at home or abroad. As his diet, for several years, consisted generally, either of bread and milk, or of bread and butter, what solid food he wanted could be supplied at any table."16

It is also testified of him, by his brother, Prof. Emerson, of Andover, that "for more than thirty years he adopted the practice of eating but one kind at a meal." If I do not misremember, for I knew him well, he was in favor of banishing flesh and fish, and substituting milk and fruits in their stead, on Bible ground. – I refer here to the Divine arrangement in the first chapter of Genesis; and which has never, that I am aware, been altered.

TAK SISSONTak Sisson, as he was called, was a slave in the family of a man in Rhode Island, before and during the Revolution.

From early childhood he could never be prevailed on to eat any flesh or fish, but he subsisted on vegetable food and milk; neither could he be persuaded to eat high seasoned food of any kind. When he was a child, his parents used to scold him severely, and threaten to whip him because he refused to eat flesh. They said to him (as I have been told a thousand times), that if he did not eat meat he would never be good for any thing, but would always be a poor, puny creature.

But Tak persevered in his vegetable and unstimulating diet, and, to the surprise of all, grew fast, and his body was finely developed and athletic. He was very stout and robust, and altogether the most vigorous and dexterous of any of the family. He finally became more than six feet high, and every way well proportioned, and remarkable for his agility and strength. He was so uncommonly shrewd, bright, strong, and active, that he became notorious for his shrewdness, and for his feats of strength and agility. Indeed, he was so full of his playful mischief as greatly to annoy his overseer.

During the Revolutionary War it became an object to take Gen. Prescott. A door was to be forced where he was quartered and sleeping, and Tak was selected for the work. Having taken his lesson from the American officer, he proceeded to the door, plunged his thick head against it, burst it open, roused Gen. P., like a tiger sprung upon him, seized him in his brawny arms, and in a low, stern voice, said, "One word, and you are a dead man." Then hastily snatching the general's cloak and wrapping it round him, at the same time telling a companion to take care of the rest of his clothes, he took him in his arms, as if a child, and ran with him to a boat which was waiting, and escaped with his prisoner without rousing even the British sentinels.

Tak lived on his vegetable fare to a very advanced age, and was remarkable, through life, for his activity, strength, and shrewdness.

CHAPTER VI.

TESTIMONY OF PHILOSOPHERS AND OTHER EMINENT MEN

General Remarks. – Testimony of Plautus. – Plutarch. – Porphyry. – Lord Bacon. – Sir William Temple. – Cicero. – Cyrus the Great. – Gassendi. – Prof. Hitchcock. – Lord Kaims. – Dr. Thomas Dick. – Prof. Bush. – Thomas Shillitoe. – Alexander Pope. – Sir Richard Phillips. – Sir Isaac Newton. – The Abbé Gallani. – Homer. – Dr. Franklin. – Mr. Newton. – O. S. Fowler. – Rev. Mr. Johnston. – John H. Chandler. – Rev. J. Caswell. – Mr. Chinn. – Father Sewall. – Magliabecchi. – Oberlin and Swartz. – James Haughton. – John Bailies. – Francis Hupazoli. – Prof. Ferguson. – Howard, the Philanthropist. – Gen. Elliot. – Encyclopedia Americana. – Thomas Bell, of London. – Linnæus, the Naturalist. – Shelley, the Poet. – Rev. Mr. Rich. – Rev. John Wesley. – Lamartine.

GENERAL REMARKSThis chapter might have been much more extended than it is. I might have mentioned, for example, the cases of Daniel and his three brethren, at the court of the Babylonian monarch, who certainly maintained their health – if they did not even improve it – by vegetable food, and by a form of it, too, which has by many been considered rather doubtful. I might have mentioned the case of Paul,17 who, though he occasionally appears to have eaten flesh, said, expressly, that he would abstain from it while the world stood, where a great moral end was to be gained; and no one can suppose he would have done so, had he feared any injury would thereby result to his constitution of body or mind.

The case of William Penn, if I remember rightly what he says in his "No Cross no Crown," would have been in point. Jefferson, the third President of the United States, was, according to his own story, almost a vegetable eater, during the whole of his long life. He says he abstained principally from animal food; using it, if he used it at all, only as a condiment for his vegetables. And does any one, who has read his remarks, doubt that his "convictions" were in favor of the exclusive use of vegetable food?

However, to prevent the volume from much exceeding the limits originally assigned it, I will be satisfied – and I hope the public will – with the following selections of testimonies, ancient and modern; some of more, some of less importance; but all of them, as it appears to me, worthy of being collected and incorporated into a volume like this, and faithfully and carefully examined.

PLAUTUSPlautus, a distinguished dramatic Roman writer, who flourished about two thousand years ago, gives the following remarkable testimony against the use of animal food, and of course in favor of the salubrity of vegetables; addressed, indeed, to his own countrymen and times, but scarcely less applicable to our own:

"You apply the term wild to lions, panthers, and serpents; yet, in your own savage slaughters, you surpass them in ferocity; for the blood shed by them is a matter of necessity, and requisite for their subsistence.

"But, that man is not, by nature, destined to devour animal food, is evident from the construction of the human frame, which bears no resemblance to wild beasts or birds of prey. Man is not provided with claws or talons, with sharpness of fang or tusk, so well adapted to tear and lacerate; nor is his stomach so well braced and muscular, nor his animal spirits so warm, as to enable him to digest this solid mass of animal flesh. On the contrary, nature has made his teeth smooth, his mouth narrow, and his tongue soft; and has contrived, by the slowness of his digestion, to divert him from devouring a species of food so ill adapted to his frame and constitution. But, if you still maintain that such is your natural mode of subsistence, then follow nature in your mode of killing your prey, and employ neither knife, hammer, nor hatchet – but, like wolves, bears, and lions, seize an ox with your teeth, grasp a boar round the body, or tear asunder a lamb or a hare, and, like the savage tribe, devour them still panting in the agonies of death.

"We carry our luxury still farther, by the variety of sauces and seasonings which we add to our beastly banquets – mixing together oil, wine, honey, pickles, vinegar, and Syrian and Arabian ointments and perfumes, as if we intended to bury and embalm the carcasses on which we feed. The difficulty of digesting such a mass of matter, reduced in our stomachs to a state of liquefaction and putrefaction, is the source of endless disorders in the human frame.

"First of all, the wild, mischievous animals were selected for food; and then the birds and fishes were dragged to slaughter; next, the human appetite directed itself against the laborious ox, the useful and fleece-bearing sheep, and the cock, the guardian of the house. At last, by this preparatory discipline, man became matured for human massacres, slaughters, and wars."

PLUTARCH"It is best to accustom ourselves to eat no flesh at all, for the earth affords plenty enough of things not only fit for nourishment, but for enjoyment and delight; some of which may be eaten without much preparation, and others may be made pleasant by adding divers other things to them.

"You ask me," continues Plutarch, "'for what reason Pythagoras abstained from eating the flesh of brutes?' For my part, I am astonished to think, on the contrary, what appetite first induced man to taste of a dead carcass; or what motive could suggest the notion of nourishing himself with the flesh of animals which he saw, the moment before, bleating, bellowing, walking, and looking around them. How could he bear to see an impotent and defenceless creature slaughtered, skinned, and cut up for food? How could he endure the sight of the convulsed limbs and muscles? How bear the smell arising from the dissection? Whence happened it that he was not disgusted and struck with horror when he came to handle the bleeding flesh, and clear away the clotted blood and humors from the wounds?

"We should therefore rather wonder at the conduct of those who first indulged themselves in this horrible repast, than at such as have humanely abstained from it."

PORPHYRY, OF TYREPorphyry, of Tyre, lived about the middle of the third century, and wrote a book on abstinence from animal food. This book was addressed to an individual who had once followed the vegetable system, but had afterward relinquished it. The following is an extract from it:

"You owned, when you lived among us, that a vegetable diet was preferable to animal food, both for preserving the health and for facilitating the study of philosophy; and now, since you have eat flesh, your own experience must convince you that what you then confessed was true. It was not from those who lived on vegetables that robbers or murderers, sycophants or tyrants, have proceeded; but from flesh-eaters. The necessaries of life are few and easily acquired, without violating justice, liberty, health, or peace of mind; whereas luxury obliges those vulgar souls who take delight in it to covet riches, to give up their liberty, to sell justice, to misspend their time, to ruin their health and to renounce the joy of an upright conscience."

He takes pains to persuade men of the truth of the two following propositions:

1st. "That a conquest over the appetites and passions will greatly contribute to preserve health and to remove distempers.

2d. "That a simple vegetable food, being easily procured and easily digested, is a mighty help toward obtaining this conquest over ourselves."

To prove the first proposition, he appeals to experience, and proves that many of his acquaintance who had disengaged themselves from the care of amassing riches, and turning their thoughts to spiritual subjects, had got rid entirely of their bodily distempers.

In confirmation of the second proposition, he argues in the following manner: "Give me a man who considers, seriously, what he is, whence he came, and whither he must go, and from these considerations resolves not to be led astray nor governed by his passions; and let such a man tell me whether a rich animal diet is more easily procured or incites less to irregular passions and appetites than a light vegetable diet! But if neither he, nor a physician, nor indeed any reasonable man whatsoever, dares to affirm this, why do we oppress ourselves with animal food, and why do we not, together with luxury and flesh meat, throw off the incumbrances and snares which attend them?"

LORD BACONLord Bacon, in his treatise on Life and Death, says, "It seems to be approved by experience, that a spare and almost a Pythagorean diet, such as is prescribed by the strictest monastic life, or practiced by hermits, is most favorable to long life."

SIR WILLIAM TEMPLE"The patriarchs' abodes were not in cities, but in open countries and fields. Their lives were pastoral, and employed in some sorts of agriculture. They were of the same race, to which their marriages were generally confined. Their diet was simple, as that of the ancients is generally represented. Among them flesh and wine were seldom used, except at sacrifices at solemn feasts.

"The Brachmans, among the old Indians, were all of the same races, lived in fields and in woods, after the course of their studies was ended, and fed only upon rice, milk, and herbs.

"The Brazilians, when first discovered, lived the most natural, original lives of mankind, so frequently described in ancient countries, before laws, or property, or arts made entrance among them; and so their customs may be concluded to have been yet more simple than either of the other two. They lived without business or labor, further than for their necessary food, by gathering fruits, herbs, and plants. They knew no other drink but water; were not tempted to eat or drink beyond common appetite and thirst; were not troubled with either public or domestic cares, and knew no pleasures but the most simple and natural.