Полная версия

Полная версияForty Years in the Wilderness of Pills and Powders

One night, while endeavoring to relieve the sufferings of one of these patients in delirium tremens, almost to no purpose, the thought struck me, "What effect would a prodigious dose of calomel have on the poor creature? Can it kill him? I doubt it. I will venture on the trial."

So, without communicating the slightest hint to any one around me of what I was about to do, I contrived to insinuate a hundred grains or more of this substance into the man's stomach, that like a chemical receiver took what was poured into it. Having succeeded in the administration of the dose, I waited patiently the issue.

The medicine had, in due time, its full ordinary effect; but the degree of its cathartic effect was not in proportion to the largeness of the dose. Its activity hardly amounted to violence. It seemed, however, to quiet the brain and nerves as if by magic; nor am I aware that any injurious effects, either local or general, ever followed its exhibition. I had the full credit of a speedy and wonderful cure.

Another fact. I was frequently called to prescribe for children who were threatened with the croup. One night, on being called to a child of some eight or ten months, I thought of large doses of calomel. Was there any great risk in trying one? I ventured. I gave the child almost a teaspoonful of this active cathartic. It was indeed a gigantic dose, and the treatment was bold if not heroic.

For a couple of hours the patient breathed badly enough. There was evidently much oppression, not only of the lungs but of the nervous system. The parents and friends of the child grew uneasy. They were not, however, more uneasy than their physician. But I consoled myself by laboring to compose them. I preached to them long and loud, and to some extent with success.

At the end of about two hours, the latter part of which had been marked by a degree of stupor which almost discouraged me, a gentle vomiting came on, followed by moderately cathartic effects; and the child immediately recovered its mental activity, and in a few days was well.

Empirical as this practice was, I ventured on it again and again, and with similar success. At length the practice of giving giant doses in this disease became quite habitual with me, and I even extended it to other diseases. Not only calomel, but several other active medicines were used in the same bold and fearless manner. I do not know that I ever did any direct or immediate mischief in this way. On the contrary, I was regarded as eminently successful.

And yet I should not now dare to repeat the treatment, however urgent might seem to be the demand, or recommend it to others. It might, perhaps, be successful; but what if it should prove otherwise? I could make no appeal to principle or precedent in justification of my conduct. It is true, I have met with one or two practitioners whose experience has been similar; but what are a few isolated cases, of even honest practice, in comparison with the deductions of wise men for centuries? There may be after consequences, in these cases, which are not foreseen. Sentence against an evil work, as Solomon says, is not always executed speedily.

CHAPTER XXXIII

THE LAMBSKIN DISEASE

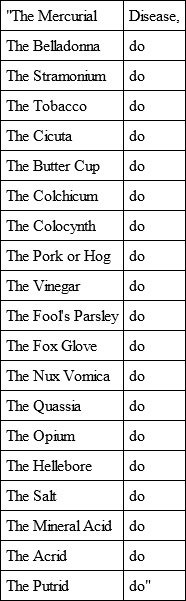

Should any medical man look through these pages, he may perchance amuse himself by asking where the writer obtained his system of classification of disease. It will not, certainly, be very easy to find such a disease as the lambskin disease in any of our modern nosologies. But he will better understand me when he has read through the chapter. He may be reminded, by its perusal and its quaint title, of the classification which is found in Whitlow's New Medical Discoveries, founded, as the doctor says, on the idea that "every disease ought to be named from the plant or other substance which is the principal exciting cause of such disease." It is as follows:

If on examination the curious reader should find no such disease as the "Lambskin disease" in Dr. W.'s catalogue, he should remember that the list is by no means complete, and that there will be no objection to the addition of one more. And why, indeed, may I not coin terms as well as others? All names must have been given by somebody.

But I will not dwell on the subject of nosology too long. I have something else to do in this chapter than merely to amuse. I have some thoughts to present on health and sickness, – thoughts, too, which seem to me of vast importance.

A son of Mr. G., a farmer, had been at work in an adjoining town, all summer, with a man who was accustomed to employ a great number of hands in various occupations, – farming, road building, butchering, etc., etc. Of a sudden, young G., now about twenty years of age, was brought home sick, and I was sent for late at night – a very common time for calling the doctor – to come and see him.

I found him exceedingly weak and sick, with strong tendencies to putridity. What could be the cause? There was no prevailing or epidemic disease abroad at the time, either where he had been laboring, or within my own jurisdiction; nor could I, at first, find out any cause which was adequate to the production of such effects as were before me.

I prescribed for the young man, as well as I could; but it was all to no purpose. Some unknown influence, local or general, seemed to hang like an incubus about him, and to depress, in particular, his nervous system. In short, the symptoms were such as portended swift destruction, if not immediate. I could but predict the worst. And the worst soon came. He sunk, in a few days, to an untimely grave. I say untimely with peculiar emphasis; for he had hitherto been regarded as particularly robust and healthy.

His remains were scarcely entombed when several members of his father's family were attacked in a similar way. Another young man in the neighborhood, who had been employed at the same place with the deceased, and who had returned at the same time, also sickened, and with nearly the same symptoms. And then, in a few days more, the father and mother of the latter began to droop, and to fall into the same train of diseased tendencies with the rest. Of these, too, I had the charge.

My hands were now fully occupied, and so was my head. Anxious as most young men are, in similar circumstances, not only to save their patients, but their reputation, and though the distance at which they resided was considerable, I visited both families twice a day, and usually remained with one of them during the night. I was afraid to trust them with others.

Physically this constant charge was too much for me, and ought not to have been attempted. No physician should watch with his patients, by night or by day, – above all by night – any more than a general should place himself in the front of his army, during the heat of battle. His life is too precious to be jeoparded beyond the necessities involved in his profession.

But while my hands were occupied, my mind was racked exceedingly with constant inquiry into the cause of this terrible disease, – for such to my apprehension it was becoming. The whole neighborhood was alarmed, and the paleness of death was upon almost every countenance.

My doubts were at length removed, and the cause of trouble, as I then supposed and still believe, fully revealed. The disease so putrescent in its tendencies, had originated in animal putrefaction. The circumstances were as follows: —

The individual with whom the young men who sickened had been residing and laboring, had laid aside, in his chamber, some time before, quite a pile of lambskins, just in the condition in which they were when removed from their natural owners, and had suffered them to lie in that condition until they were actually putrescent and highly offensive. The two young men, owing to the relative position of the chambers they occupied, were particularly exposed to the poisonous effluvia.

I did not forget – I did not then forget – the oft inculcated and frequently received doctrine, that animal impurity is not apt to engender disease. It most certainly had an agency – a prominent one – in the case before us. Perhaps it has such an influence much more frequently than is generally supposed.

One of my patients, in the family which I first mentioned, – a little boy two or three years old, – died almost as soon, after being seized with disease, as his elder brother had done. The rest, though severely sick, and at times given over to die, finally recovered. Some of them were sick, however, many months, and none of them, so far as I now recollect, – with perhaps a single exception, – ever enjoyed as good health afterward as before.

I had in these families six or eight of the most trying cases I ever had in my life; and yet, with the exceptions before named, all recovered. How much agency my own labors as a medical man had in producing this result, I am at a loss to conjecture. As an attendant or nurse, I have no doubt my services were valuable. And it was because a good nurse is worth more than a physician that I so frequently ran the risk of watching over the sick so closely as considerably to impair my own health.

The neighbors and friends of the two sick families, as I have already intimated, looked on in silent agony during the whole campaign; expecting, first that their families, too, would soon be called to take their turn; and secondly, that I, the commander in chief, should be a sufferer, which of course would be a great public disadvantage. They were almost as much gratified as I, when we all came forth from the fire unscathed.

On the whole, except as regards health, I was a gainer rather than a loser by the affair. I mean, of course, in the way of medical reputation. I was by this time fairly established as a powder and pill distributer, of the first water. In other words, I was beginning to be regarded as a good family physician, and to be sought for, not only within the narrow limits of my own native township, some four or five miles square, but also quite beyond these narrow precincts. Occasionally I had patients in three or four adjoining towns, and I was even occasionally called as counsel to other physicians. My ambition was high, perhaps higher than it ought to have been; but it had its checks and even its valleys of humiliation; so that on the whole I retained my sanity and a full measure of public confidence.

And yet, in conclusion, I have to confess that besides exposing my own health, I made many medical blunders. I would not again run the risk to health or reputation which, during this long trial of several months, I certainly ran, for any sum of money which king Croesus or the Rothschilds could command. Nor do I believe an intelligent physician can do it, without being guilty of a moral wrong. Every one has his province; let him carefully ascertain what that is, and confine himself to it. The acting commander in an important military expedition has no right to place himself in the ranks of those who are about to leap a ditch, scale a wall, or charge bayonet. Paul has no right to labor in Athens when he knows perfectly well that he can do more good in Jerusalem, and the voice of God, by his Providence or otherwise, calls him thither. And "to him that knoweth to do good and doeth it not, to him it is sin."

CHAPTER XXXIV

MILK PUNCH FEVER

A certain young woman who had great general confidence in my skill, after I had stood by her many long hours in one of Nature's sorest trials, was left at length in a fair way to recover, except that she was exceedingly exhausted, and needed the most careful attendance on the part of those around her. She no longer needed any medicine, nothing but to be let alone. In other words, she needed nothing but good nursing and entire freedom from all care and responsibility.

Being obliged at this juncture to leave her for nearly the whole night, I gave the best directions to her principal nurse of which I was capable, as well as the principal reasons on which it was founded. She seemed entirely submissive, and perhaps, in theory, was so. But in my zeal to make them understand that I was acting on common-sense principles, I committed one error, a very common one, indeed, but yet an error. It was that of reasoning with them with a view to make every thing particularly intelligible. One has authority, in these matters, as long as he takes the attitude of authority, but the moment he descends to the general level of his patients, and in true republican style puts himself on a par with them, he begins to lose their confidence as a physician. You may not be sensible of a loss of this sort, nor even the physician. You may even think the reverse were more true. But you deceive yourself. Though your patients may love you better as a friend or even as a father, yet they have lost confidence in you medically, in nearly the same proportion. Strange indeed that it should be so; but so, according to my own observation, it ever has been. That a prophet is "without honor" – and most so in his own country and among his own personal friends – is as true now as it was eighteen hundred years ago.

Had I told Mrs. D.'s attendants to do so or so, and left them without saying a word more, they would probably have done it. But I had condescended to reason with them about the matter; their belief that medical men dealt with the stars, and spoke with a species of supernatural authority, had been shaken; and they were emboldened to reason on the subject, and to hearken to the reasonings as well as to what had but the slightest resemblance thereto in others, during my absence.

Having occasion to use all possible precaution against the supervention of milk fever in my patient, I left particular directions that nothing stimulating should be administered, and assigned several good, substantial reasons. No food was to be given, except a little bread and some plain chicken broth, with no condiment or dressing but a little salt; and this at intervals of about four hours. No drink – not a particle – was to be given, except frequent very small draughts of cold water.

While I was absent Mrs. D.'s mother came into their family, not only to rejoice with them in an accession to their number, but to render them a little aid. She was one of those mothers whose kindness so often defeats their best and purest intentions. She was all eyes, ears, and attention, and nearly all talk. The daughter's treatment soon underwent a special scrutiny, and was found "wanting."

"Has the doctor ordered my daughter no milk punch?" she said to the attendants. "Not a drop," they replied. She raised both hands in astonishment. "How, then," she asked, "can the ninny expect she can ever have any nourishment for that boy?" The attendants could not inform her. "The doctor," they said, "gave reasons," but they could not fully understand them.

"He did not probably understand them himself," said she. "There are no reasons against it, I am confident. It is only a notion of his. These young doctors are always full of their book wisdom. Why, a little experience is worth a whole world full of theories. Now I know – and so does every other person who has nursed children – that a little milk punch, in these cases, is necessary. Not a great deal, it is true; but a little, just enough to give the system strength. Nature is weak in these cases. I wish some of these young doctors themselves were obliged to endure the trials we have to endure, and we should see whether they could get along with no drink but cold water!"

The rebellion soon reached the daughter's ears, who, till now, had confided in the "doctor's" prescription, and was doing well. She was soon as uneasy with things as they were, as her mother and the nurse and the neighbors. The husband was not of the clique; but then he was one of those good-natured men who leave every thing to their wives; and though they may not fully approve of every thing that is attempted, will yet do and refrain from doing many things for the sake of peace. He interposed no veto on the present occasion.

The mother, in short, soon reigned "sole monarch," and proceeded to issue from her imperial throne, the sage decree that a little milk punch must be made. Judith, the nurse, was to have it prepared so and so, and she would herself administer it. Only just so many spoonfuls of rum must be added to the tumbler of milk and water, and just so much sugar. It must be weak, the decree said.

Mrs. D. drank freely of the punch, because her mother told her that it would do her good. True, she asked after the first swallow, "what will the doctor say to this?" but her mother bade her be quiet, she would see to all that. "It is made very weak," said the mother, "on purpose for you; drink of it a little and often. It will be both food and drink to you. It will be good for the babe, dear child! how can these doctors wish to starve folks? I have no notion of starving to death, or having my children or grandchildren starved."

It was now past midnight, and Mrs. D. had as yet slept but very little. Had she simply followed out my directions she might have slept an hour or two before midnight, and several hours in the aggregate afterward. This, though done by stealth and in short naps, would have given her more real rest and strength than a whole gallon of milk punch, and instead of kindling fever, would have carried off all tendencies of the kind.

On my arrival, early the next morning, I found a good deal of headache, such as cold water and plain food and rest seldom, if ever, create. My fears were at once excited, and they were greatly strengthened when I saw her mother. But the blow had been struck, and could not be recalled. Mrs. D., in short, was already in the beginning stage of a fever which came within a hair's breadth of destroying her.

It is indeed true that she finally recovered. No thanks, however, were due to the mother's over-kindness, nor to my own over-communicativeness. Had I done my duty, had I kept my own counsel, nobody, not even the mother herself, as I now verily believe, would have ventured to disobey my positive injunctions. And had this mother done, as she would have been done by in similar circumstances, all would probably have been well still. We should have saved a little reputation, and a good deal of health.

I learned, I repeat, from this unexpected adventure, that it was wisdom to keep my own secrets. I do not say that I have always acted up to the dignity of this better knowledge, but I am justified in saying that I have sometimes profited from an acquaintance with human nature that cost me dear. It is no trifle to see an individual suffer from painful disease a couple of weeks, and jeopard the life of a child during the whole time, when a little knowledge how to refrain from speaking ten words of a particular kind and cast, would have prevented every evil.

CHAPTER XXXV

MY FIRST CASE IN SURGERY

My first surgical case of any magnitude, was that of a wounded foot. For, though I had been required to bleed patients many times, – and bleeding is properly a surgical operation, – yet it had become so common in those days, and was performed with so little science or skill, that it was seldom recognized as belonging to the department of surgery.

One of my neighbors had struck his axe into the upper part of his foot, and cut it nearly through. Happening to be at home when the accident occurred, which was in my own immediate neighborhood, I was soon on the spot, and ready to afford assistance; and, as good luck would have it, the man was not at all weakened by loss of blood, at my arrival.

My lesson from an old surgeon4 was not yet forgotten. I still knew, as well as any one could have told me, that to put together the divided edges of the wound and keep them there, was half the cure. But how was this to be done? Slips of adhesion plaster would bring the divided edges of the wounded surface into their place, but would the deeper-seated and more tendinous parts unite while left without touching each other? Or should a few stitches be taken?

The wound was lengthwise of the foot, and no tendons were divided. I made up my mind to dress it without any sewing, and acted accordingly. The bleeding soon ceased. When all was secured, the patient inquired what he should put on it, to cure it. Had he not raised the question, I might, perhaps, have followed out my own ultra tendencies, and left it without any application at all; but as it was, I concluded to order something on which he might fasten his faith, – something which, though it should do no good, would do no harm.

"Nothing is better for a fresh wound," I said, "than the 'Balsam of Life.' Just send Thomas over to Mr. Ludlow's, and get a couple of ounces of his 'Balsam of Life.'" It was soon brought, and the surface of the wound and its bandages moistened with it. "Now," said I, "keep your foot as still as you can till I see you again. I will be in again before I go to bed."

I called again at nine o'clock in the evening. All appeared well, only the patient had some doubts whether the Balsam of Life was just the right thing. Several of the neighbors had been in, as he said, and, though they admitted that the Balsam might be very good, they knew, or thought they knew, of something better. However, I succeeded in quieting most of his rising fears for the present, by assuring him that nothing in the wide world was equal, for its healing virtues, to the "Balsam." My voice here was law, for I gave no reasons!

On making inquiry, afterward, with a view chiefly to gratify curiosity,5 I found that the first individual who came in after I had left the house, assured them there was nothing so good for a fresh wound as a peach leaf. The next, however, insisted that the best way was to bind up the part in molasses. The third said the best way was to take just three stitches to the wound, and bind it up in the blood. The fourth said the most sovereign thing in the world, for a fresh cut, was tobacco juice!

Now I could have told these various representatives of as many various public opinions, that all these things and many more which might have been named, are, in a certain sense, good, since any mere flesh wound, in the ordinary circumstances of ordinary life, will heal in a reasonable time, in spite of them. I could have told them, still further, that the Balsam of Life was probably little, if any, better than the other things proposed, any farther than as it secured more faith and confidence, and prevented the application of something which was worse. I could have assured them that all the external applications in the world are of no possible service, except to defend from cold air, and prevent external injuries, or reduce inflammation; and that the last-mentioned symptom, should it occur, would be best relieved by cold water. But what good would it have done? Just none at all, according to my own experience. Positive assurance – mere dogmatism – was much better.

The wound did well as it was, though it might have done much better, could the patient's faith have been just as firmly fixed on nothing at all but Nature, as it was on medicaments. However, the tincture I proposed, which somebody had dignified with the name of Balsam of life, had done very little harm, if any, to the parts to which it had been applied, while it had done a great deal of good to the patient's mind, and the minds of his friends. It was nothing, I believe, but a compound tincture of benzoin. I have used it a great number of times, and with the same wonderful results. The patient always gets well, either on account of it, or in spite of it! Does it make much practical difference which?

CHAPTER XXXVI

EMILIA AND THE LOVE CURE

One young family on whom I was accustomed to call from time to time, was not only accustomed to send for me in the night, as did many others, but, what made it much worse for me, they resided some four or five miles distant, among the mountains. They were of that class of people who look every man on his own things, and never, as the apostle would enjoin, on the things of others. They knew very well that a physician, though he might be half a conjuror, required sleep; still, they were willing to finish their day's work, eat their supper, perform a large number of et ceteras, even if they did not call for the doctor till he had fairly taken off his boots to retire for the night. But there was one consolation in all this, that they paid me promptly; and medical men, as you know, like other men, work for pay. They cannot live wholly on air.