Полная версия:

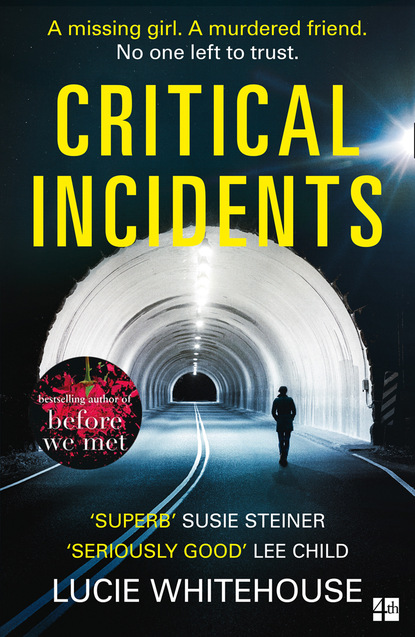

Critical Incidents

‘No.’

‘It was on the radio on the way over. Heart, just local. Same thing, looking for Josh, nothing we don’t already know.’ She reached for the radio. ‘Want to see if we can catch it again?’

As Robin shook her head, her phone buzzed in her pocket, a text. Gid? Eight o’clock, a few minutes after – he could just have come on shift. A small leap of hope: perhaps there’d been movement on Hinton. But no, when she took out the phone, the screen said ‘Adrian’. It was mildly startling, the name already an anachronism.

Len just told me about Corinna. Devastated for you. Here if you need me. A

For god’s sake. She couldn’t stop them being in touch – she didn’t want to, they loved each other, and it was good for Len to have a male figure in her life – but of course it meant Adrian would hear about everything that happened to them. Was he going to use this to reopen communication, even try to make her reconsider? She’d thought at least that was over and done with. She locked the phone and put it back in her pocket – she’d deal with it later.

‘Where are we going?’ she said.

‘Val Woodson’s, via coffee. I can’t be messing with that Nescafé this morning.’

‘You’ve taken her on?’

‘I’ve told her we’ll see what we can do, yeah. She’s desperate and I want to help her.’ Another pause. ‘I also thought it would be good for you.’

‘Me?’

‘It’s what you need now, isn’t it? Something to get your teeth into – something where you can actually use your skills.’ She glanced over. ‘It’s going to be very hard for you, being on the outside while this is going on. I thought this would give you another focus, something else to think about.’

‘Thank you,’ Robin said.

She watched Stratford Road slide past outside the window, One-Hour Photo and the Kerala Ayurvedic spa, a place offering cash for gold. Outside UK Furniture Clearance, a ragtag assortment of wooden cots, bedframes and awkward-looking cabinets metastasized on the pavement. She concentrated, focusing on details, looking for something she could throw a line around. If anything, the unreality was stronger this morning, the lack of sleep compounding the sense that what had been concrete was now wily, unreliable. Malign. The world had spun away – she was out on her own, free-falling.

A couple of minutes later, Maggie pulled into a spot outside a bakery three times the size of the travel agent and sari shop either side. Weddings, Parties, Functions read the awning, while photographs propped at the bottom of the plate-glass window showed enormous, multi-tiered cakes in colours and degrees of ornamentation from subtle to Bollywood. At eye level, a poster offered Morning Breakfast Deals at astonishing prices. Fried egg, two toasts and beans, £2.75 – you’d be lucky to get a single slice of toast for that in London.

‘Come with me,’ said Maggie, undoing her seatbelt. ‘Meet Gamil.’

Inside, the air was heady, the smell of coffee and eggs on the griddle cut with condensed milk, coconut and cinnamon. On the right, a long glass cabinet displayed ranks of Indian sweets in pinks and greens and caramel tones. Kaju barfi, mysore pak – an image suddenly of Aisha’s wedding, the boxes and boxes of sweets they’d pressed on her because they all knew – it was a family joke – how much she loved them. Robin shook her head, flicked the memory away.

‘Maggie.’ A man in his mid-fifties stepped out from behind the counter, pulling off a pair of blue gloves. He dropped them in a bin and came to greet her, taking her hands in his. ‘We haven’t seen you for ages.’ Indian sing-song met Brummie sing-song, his voice all music. Heavy-lidded eyes with extravagant bags looked out from a face that was otherwise remarkably line-free. His hairline had receded parallel with his ears, and the deep exposed forehead and long nose with its arched nostrils gave him an avian look. At the same time, he had something French going on, the thick white cotton shirt with cuffs rolled to the elbow, perhaps, or the tan loafers. An Indian Serge Gainsbourg, minus the sleaze.

‘I haven’t had much over here lately,’ Maggie said, ‘but we might do for a bit and I wanted to introduce you to my friend Robin. Friend and colleague – we’re going to be working together.’

‘Robin? My pleasure.’ A firm, dry handshake. ‘Coffee for two? I’ve got a fresh pot this side, just done.’

‘How are things with you?’ Maggie looked at the line of people queuing to order breakfast sandwiches. ‘You’re mobbed.’

‘Yes, morning rush, always busy, busy.’ He went back behind the sweets cabinet and pulled paper cups from a long stack. ‘Just as well – three kids at university. Have I seen you since? Wasim got a place at Nottingham. Computer Science.’

‘Younger son,’ Maggie said. ‘He helps out in the shop sometimes, you might meet him if we’re over here. That’s smashing, Gamil, congratulations.’

‘Last one. Just the A-levels now and then, pouf, all my little birds flown. Now, what are you having? Doughnut, flapjack? New muffins are just out of the oven.’

‘You’re all right, thanks, love. Still playing chicken with the diabetes express here, so I resist on the very few occasions I can do it without chewing my arm off. Rob?’

‘No. Thank you.’

He brought the coffees over and put them on top of the display counter. ‘Very hot – careful. Omelette’s good if you don’t want sugar. I can make it for you myself.’

‘Thanks, this’ll do me.’ Maggie inhaled a vaporous sip from the top. ‘Now, ulterior motive, I wanted to ask you if you know someone.’ She reached inside her long suede coat and brought out a folded sheet of A4 printed with a grainy photo. ‘He’s basically the mayor of Sparkhill,’ she said to Robin. ‘Knows everyone round here.’

Gamil rolled his eyes. ‘Show me.’

Maggie handed it over and he unhooked a pair of glasses from the V of his shirt and put them on. ‘Yes,’ he said, ‘I don’t know her but she gets the bus just outside, comes in two or three days a week to get something to take with her. Friendly girl, says hello, good morning. She lives somewhere up that way.’ He gestured towards the shop door, left, in the direction of Valerie Woodson’s house.

‘You don’t know her name?’

‘Wasim might. Though she looks a bit older, more Faiza’s age?’

‘Yes, she left school three or four years back. Can you remember when you last saw her?’

‘Not today. Not yesterday but I was in the kitchen a lot so … Last week, yes, that big rainstorm – Tuesday, Wednesday – the bus shelter was full so I said to the people come and stand under cover. She was there.’

‘Have you ever heard anything about her?’

Gamil smiled at Robin. ‘She thinks I’m a gossip.’

‘You are a gossip,’ said Maggie.

He shook his head. ‘So mean to me. No, no rumours.’ He passed them plastic lids from a box on the counter behind him. ‘I see her walk past sometimes at the weekend, too, maybe shopping, but otherwise …’

‘How do you know she lives up that way?’ Robin asked.

‘Ah.’ A small frown, eyebrows drawing together. ‘You’ve reminded me. There was one time, I remember it – just before Divali, the end of October – I was coming in early to deal with the festival orders, walking, and I saw her.’

‘Early?’

‘Four, four thirty – still dark. Bakery hours, you know.’

‘What was she doing?’

‘Getting out of a taxi. Coming home from a party, I think – she was a bit … wobbly. Big shoes, heels – she took them off, walked barefoot up the street in that direction.’ He mock-shivered. ‘Too cold. She was in one of those unlicensed taxis. Like a normal car. Maybe Uber, no way to be sure.’

‘How did you know it was a cab?’ asked Robin.

‘She got out of the back, but when it went by, the front passenger seat was empty.’ He shook his head. ‘Too dangerous – how do you know who you’re getting? When she left home, I made Faiza promise, promise me she would never do that. Black cabs only, I said, send me the receipts, I’ll pay. I meant to say something to her the next time I saw her,’ he tapped the paper with his fingertip, ‘this girl. But I forgot. May I ask what’s happening with her?’

Maggie nodded. ‘She’s gone missing.’

Becca’s room was at the rear of the house, its narrow sash window overlooking the side return, a tiny yard and the red-brick backs of the houses behind. The bed was a single, tucked tight into the corner, but it ate up almost a third of the floor space anyway, leaving an L-shaped peninsula of carpet barely wide enough to walk around. The redundant chimney breast took a big chunk, too, and created two deep alcoves, one that housed a wardrobe, the other a chest of drawers topped with a pine-framed mirror.

Despite its size, the room was quite appealing. Robin had expected clutter, slippery stacks of magazines, heaps of clothes, a sticky basket of make-up slowly gathering dust, but instead it was minimalist. The two magazines on the shelf of the tiny bedside table – she stooped: Elle and Heat – were both lined up squarely under a library copy of Veg Every Day and a well-worn paperback Jane Eyre. The bedcover was white seersucker, the anglepoise-style lamp brushed steel. A shot glass held a tiny cactus.

‘You haven’t cleaned up in here?’ Maggie asked.

‘No.’ Valerie hovered at the threshold, anxiety rising off her like a heat haze. Another person who didn’t sleep last night, Robin had thought when she opened the front door. She knew about Corinna, Maggie had told her yesterday on the phone, and as she’d come in, Valerie had touched her arm. ‘I’m so sorry about your friend.’

‘The police asked me that, too, when they looked,’ she said now. ‘She always keeps it like this – she says it feels bigger when it’s tidy.’

‘Is anything missing, that you know of?’ said Maggie.

‘No, I’ve checked. Her jewellery’s all there.’ She pointed to a lacquered box on the chest. ‘Not that she’s got much that’s worth anything, just the two rings Graeme’s mother left her and a charm bracelet. I looked for her overnight bag, just in case, but it’s still in the bottom of the wardrobe. She only had her handbag.’

A shallow bamboo tray next to the box held a liquid eyeliner, mascara, and an eyeshadow palette in matte greys. Without touching it, Robin read the bottom of a Maybelline lipstick: Very Cherry. ‘Is this the make-up she uses?’

Valerie nodded. ‘She’s got another lipstick in her bag but, normally, if she’s going on somewhere after work, she takes all this with her.’ Her voice became a croak.

Maggie went back to the doorway and put her hands on her shoulders. ‘Valerie, love, I know it’s bloody impossible but try to give yourself a break, will you? You’re going to wear yourself out. Why don’t you have a cup of tea and we’ll come down when we’re finished? We’ll be very careful.’

Valerie hesitated then nodded, her eyes shining with tears.

They waited until they heard shoes on the kitchen tiles and a rush of water in the pipes. ‘Here,’ Maggie passed Robin a pair of exam gloves from her bag and put on a pair herself. She squeezed round behind her, opened the wardrobe and looked inside. ‘I’ll do this, you take the chest.’

Robin tugged the shallow top drawer open, feeling the twinge in her shoulder. After Lennie had gone to sleep, she hadn’t risked moving, and she’d come round from the semi-conscious state she’d eventually fallen into to find one arm completely dead. Crouching toad-like, trying not to wake her, she’d extricated herself via the end of the bed, smacking her head on the top bunk as she’d stepped down.

Becca’s underwear was a mix of comfortable black cotton and skimpier, lacier things in fuchsia pink, blue and jade green designed to be seen or at least worn for a bit of a private confidence boost. Like the rest of the room, the drawer was tidy – not Christine-standard by any stretch, but neater than her own by a factor of about five; the socks in pairs, for example, rather than a static knot tossed in straight from the dryer.

T-shirts, then sweaters, all redolent of fabric softener. Robin worked her way steadily through them, shaking things out then refolding and laying them carefully on the bed. She ran her fingertips into the corners of each drawer and took out the striped lining paper. No photos taped underneath or love letters cajoling her to run away, leave it all behind; no little bag of resin or pills or even a cheeky packet of Marlboro Golds.

The clothes were cheap – H&M, Primark, Zara; tops in rayon and flimsy cotton, the knitwear more manmade fibre than wool – but they’d been taken care of, ironed and neatly folded. They’d been chosen carefully, too. The going-out things had net panels and lacy bits – racy enough – but almost everything had some design, a detail that gave it a bit of flair: a ballet wrap, a boat neck, ties at the wrists.

For all the times she’d done it, Robin hated going through people’s intimate stuff. Even in a situation like this, where the aim wasn’t to incriminate but to learn, maybe find a lead, it made her feel grubby. The thought of some sweaty-fingered DC raking through Corinna’s underwear made her want to puke all over again. But maybe it wouldn’t happen – couldn’t. Given the extent of the fire damage, Corinna’s clothes had likely been reduced to a heap of ash and melted hangers. Even if they hadn’t been destroyed, none of them would be worth keeping; those that weren’t burned would be drenched, and if they’d escaped even that, they’d reek so strongly of smoke that no one who’d loved Rin could ever bear to go near them. At least Di would be spared the task of sorting through her daughter’s things. But by the same token, there would be nothing for Peter to bury his face in, nothing left that smelled of his mother. Robin pressed the idea, running her finger along it as if it were a blade. She wanted it to hurt, to cut through to the ball of potential pain she still hadn’t been able to access. Why couldn’t she cry? What was wrong with her?

With a screech on the rail, Maggie pushed things to one side and took out a black body-con dress. She held it up to the light.

‘She bought that in the sales last month.’ Valerie appeared in the mirror behind her. Robin jumped, and turned around.

‘Sorry, I didn’t mean to … She and Lucy – her best friend – they got up at four o’clock to go. The trousers she was wearing when she … She got them sixty per cent off – she was so chuffed. She bought me a cardigan, too. That’s Lucy.’ In a second, Valerie was at Robin’s side, pointing to a photograph tucked into the mirror-frame of a pretty girl with light brown hair twisted into a top-knot. She wore a strappy, gym-type T-shirt and her face was flushed and shiny with sweat. ‘They did a 10K run last April, the three of them.’

‘He being the third?’ Robin pointed at the man with his arm around the girl’s shoulders, same age, mixed race. Eyes closed against the sun but grinning, a near-empty water bottle hanging between the fingers of his other hand.

‘Harry, yes.’

‘They look close – are they together?’

‘Lucy and Harry? No. Lucy’s going out with Cal – Calvin. They’re just friends, the three of them. I always worried about that – three’s a crowd – but it works. They’ve been friends for years, since they all started at Grafton House.’

‘Grafton House?’ said Maggie. ‘The private school?’

‘Graeme had a life-insurance policy. That’s what I spent it on. We talked about it before he died. She went to state school until she was eleven, then Grafton.’

‘Do you have Lucy and Harry’s numbers?’

‘I’ve got hers – she’ll be able to give you his.’

‘Thanks.’

‘Becca and Harry were never involved?’ said Robin.

She shook her head. ‘As I say, it’s always just been platonic.’

Missed opportunity, Robin thought; he was fit. She heard Corinna’s voice suddenly, dust-dry, ‘For god’s sake, Rob. I’m dead, you’re trying to find someone who’s probably dead as well – a little focus, perhaps?’

The pain – longing, loss, a desperate urge to laugh; it was sheer luck that she didn’t yelp. She caught her own eye in the mirror – steady, steady – then Valerie’s. She looked away, took a deep breath. A little focus. ‘Yesterday,’ she said, ‘when you told us you checked in with her work because her bed hadn’t been slept in – was that unusual? If she doesn’t have a boyfriend. Does she stay over with friends? How often doesn’t she sleep here?’

There was a pause, small but marked. ‘It was when I found the phone as well that I started worrying, not just the bed. Rebecca’s twenty-two. She can stay out, can’t she?’

‘Of course.’ Maggie, soothing.

‘But just to be clear, you mean with men?’ Robin pressed.

‘She’s an attractive girl, she’s never gone short of attention. She has flings, yes. One-night stands.’ Valerie locked eyes with her, as if daring her to be shocked.

You’ll have to try harder than that, Robin thought. ‘Has she been doing it lately? Staying out, I mean?’

‘Yes.’

‘Would she go home with someone she’d never met before? A stranger?’

Valerie turned to the window, biting a piece of dry skin on her lip between her eye teeth. ‘I don’t know. No, of course I do. She would. Yes.’

Chapter Six

When Robin was in her final year of junior school, a local woman was kidnapped. Stephanie Slater was twenty-five, an estate agent, taken from a house she’d been showing in Great Barr, only a few miles away in the north of the city. It became a major national news story, one of the biggest manhunts in British history. Christine and Dennis whispered about it in the other room, waited ’til she’d gone to bed to watch the news, but the details had been in the air, all anyone could talk about: the ransom money snatched from a railway bridge, the coffin-sized box inside a green wheelie bin in which Slater had been locked in darkness for eight days, told that if she moved she’d be electrocuted. After she was released, she described how she’d talked to Michael Sams, and kept talking, so he’d be forced to understand that she was a person, a human being. Her bravery and presence of mind probably kept her alive.

Michael Sams, badger-faced, wooden-legged Michael Sams – by the following year, when Robin started at the grammar school and met Corinna, he’d become a playground bogeyman, the shadowy figure who offered you the bag of sweets, who shoved you into the back of a van as you walked home from the corner shop at twilight. Michael Sams’ll get you.

And then, two years later, barely fifty miles away in Gloucester, came Fred and Rose West.

She and Rin were twelve turning thirteen by then: prime-time adolescence. It had gone on for weeks, the systematic taking-apart of the house at Cromwell Street where, over decades, Fred and Rose had together raped, tortured and killed young women, including their own daughters. White forensic suits on the news, day after day, week after week, another set of remains and another and another, in the garden, in holes dug in the cellar floor. Again her parents had tried to shield her but away from Dunnington Road, she and Rin had followed the news with a horrified fascination, reading the papers, watching the news at Rin’s place when Di was at work and Will, babysitting, was doing his homework in the other room. There were few stories, thank god, as depraved as that. Rose was found guilty on ten counts of murder; Fred, charged with twelve, never stood trial. He committed suicide while on remand at Winson Green, HMP Birmingham, just a handful of miles up the road. Robin remembered: it was New Year’s Day.

Two of the biggest crime stories of the decade, both local, both sexual violence against young women, a double whammy that happened just as she and Corinna became aware of the news, aware that they were – or soon would be – young women, and that monsters were not just in books but opening their car doors to offer you a lift in the rain.

It started with Stephanie Slater, her bravery as she lay alone in the dark, injured and terrified. To Robin, she became a hero, a symbol of strength, and when the Wests and their house of horrors came to light, Robin had an epiphany: that was what she wanted. She wanted strength. She wanted to be a hero. She wanted to break down the door and rescue the next Stephanie Slater. She wanted to be the one who followed the Wests home, kicked Fred in the bollocks, and pulled the girl away from the car, the teetering edge of the void.

That was what she told anyone who asked why she’d decided to go into the police. Over the years, she’d made it sound more and more ridiculous – Behold the high-kicking, karate-chopping teen ninja girl! Marvel at the self-importance, the naivety! – but it was true; it had been the first reason before she had another.

Maggie hadn’t followed the Slater case in the news: she’d worked on it. Not immediately, on the original core team, but as soon as the investigation started to expand. Unsurprisingly, it loomed large in her memory. She’d kept quiet at Valerie’s, of course, but in the car on their way here to the office, she’d brought it up.

‘Kidnap for ransom? Really?’ Robin was dubious. Nothing about the Woodsons’ set-up said money, and Valerie’s only real savings, she’d told them, were in a small private pension that wouldn’t mature for another seventeen years.

‘Remember the Slater case?’ Maggie said. ‘It was her employers, the estate agents, that Sams went after – he wanted their insurance money. Valerie might not have much but Becca works for a silversmith.’

Hanley’s. Battered floral address book in hand, Valerie had given them the number. ‘They make photo frames and candlesticks,’ she said. ‘Hip flasks and the like. Corporate gifts.’

‘They’d have had a demand by now, wouldn’t they?’ said Robin. ‘Thursday to Tuesday – five days?’

‘Yes. Unless …’ Maggie had glanced across. ‘Julie Dart.’

Mentally shafted as she was, it had taken Robin three or four seconds to connect the dots. Then she did.

The investigation into Sams had expanded beyond Stephanie Slater. Based on similarities in the two cases, West Yorkshire Police believed that a year earlier, in Leeds, he had abducted another woman – if woman was the word. Julie Dart had been just eighteen when he’d taken her, a kidnapping ‘dry run’ that went wrong; she’d managed to escape from the coffin-sized box and he’d returned to find her desperately trying to get out of his workshop. He’d killed her.

‘If there’d been a demand, we wouldn’t be on the case, obviously – the police would be all over it,’ Maggie said. ‘But if something went wrong, he – or they – might not have got that far. He might have killed her, jettisoned the plan, like Sams did.’

‘But if it is abduction, don’t you think a sexual motive’s more likely?’

‘I do. But all lines of enquiry at this stage – everything’s on the table until we get something solid. What else? There’s a new notebook in the glovebox there; let’s get some of this down.’

The list was on the table in front of Robin now, a spiral-bound page of parental pain from basic heartbreak to worst nightmare: she’d met someone and run away, upped and left; had an accident; overdosed; killed herself; been killed. The only good-news scenario, really, was that she’d needed to get away and had taken a break somewhere to clear her head. But then why not tell her mother, especially when they were so close? Why put her through this? And wouldn’t she have taken something with her – a few clothes, her washbag? The only things she could see were missing, Valerie said, were the clothes she’d walked out in that morning.

And then there was her phone.

‘Anything in her online stuff?’

Robin clicked back onto Facebook as Maggie stood and came around the table. The picture she’d been looking at was a social-media classic. Taken the Christmas before last, fourteen months ago, it showed Becca and Lucy with their heads together, big living-our-best-lives grins. Slight over-exposure made their lineless skin near-perfect. They were both wearing beanies – Becca’s navy and studded with little silver beads, Lucy’s dark burgundy with a scarf the same colour – and both had long wings of hair protruding from their hats like Afghan ears, Lucy’s light brown, Becca’s darker. In their hands were red cardboard cups, presumably the hot chocolate for sale at the stand behind them, beyond which, just visible, were the Palladian columns of the Council House in Victoria Square. Christmas Market with my bestie! Becca had written. Love winter!