Полная версия:

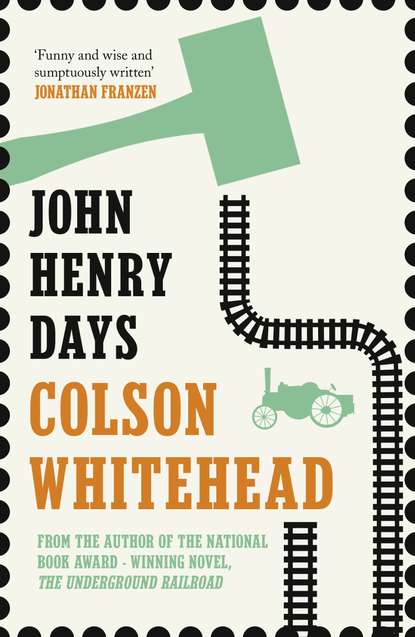

John Henry Days

Frenchie, for his part, retains an accent from his internment at a French boarding school during his adolescence. His parents were world-traveling sophisticates who unloaded their offspring with paid attendants half the year; the migrant’s ways are in his blood. Tall and slender, proud owner of a shiny black mane, this lipless wonder has cultivated a satisfied Parisian air that serves him well while playing footsie with the editors of women’s fashion magazines. For the world of international fashion is Frenchie’s specialty, he knows where to buy rice cakes and had been linked in the gossip pages to that new Italian runway model before she discovered her bisexuality. She appeared to evaporate with every step and was perceived to be the marvelous avatar of a current brand of beauty. Frenchie took his expulsion from the empyrean badly; he had ascended from reporter-of to reported-upon, his name inflated in bold type among the gossip ledgers, and now he is back in the trenches. The other junketeers saw it coming; those they write about are not their kind, and mixing with them can only lead to heartbreak.

“No sign of the van?” Frenchie asks. He looks down at his suit and, distressed, returns the tips of his shirt collar to the outside of his jacket, where they sit like the wings of a shiny red bird.

“Should be here any minute,” Dave says.

They are joined in the parking lot by a lithe young woman who is clearly not from around here; it is in her walk, a rapid skitter that places her from New York City. J. has found himself trying to slow down ever since he arrived at Yeager Airport, to get into the groove and pace of the state as a sign of openness to a different culture. The woman looks down the driveway and lights a cigarette. Waiting, like them, but no reporter. J. and his fellow junketeers are in Talcott (or just outside it, he doesn’t know) because they have committed to a lifestyle: their lifestyle pays air freight and they board planes. But why is she here? She wears faded jeans, a yellow blouse with a flower embroidered over her heart. She shifts in her boots, stamps out half a cigarette and lights another while the junketeers shoot the shit and catch up.

“It’s not here yet?” Lawrence fumes, emerging from the office with a cell phone limp in his hand, no doubt making comparisons between the publicity apparatus here and in New York and L.A. They don’t know how to do things here. “The van was supposed to be here ten minutes ago.”

“Patience, Lawrence,” Dave says.

Lawrence presses a few numbers into his phone, to beeps.

“We used to read the story of John Henry in kindergarten,” Tiny says. “The school board told the teachers they couldn’t teach Little Black Sambo anymore, so they switched over to this picture book of John Henry’s competition. Positive imagery.”

“You sound disappointed,” J. says, glancing quickly at the woman for her reaction.

“I was, a little. I don’t mean to be un-p.c.,” Tiny says. He is the kind of man who says, “I don’t mean to be un-p.c.” a lot. “But I liked Little Black Sambo. My mother used to read me Little Black Sambo when she tucked me into bed at night. It’s a cute story underneath.”

“You were undisturbed by the eyeholes cut out of the pillow you lay your little head on.”

“They were different times, J.”

“Did you hear I got a new job?”

“What?”

“It’s at the department of no one gives a shit and you’re my first client.”

“Here it comes now,” Frenchie says.

The battered blue van pulls up, New River Gorge Taxi stenciled on its side. It looks like it has been tossed by tornadoes. Workhorse of the robust fleet, J. says to himself. The driver, a ruddy-faced chap from the nabe, rolls down the window and asks, “You all going to the Millhouse Inn?” His brown, glinting hair is tucked precariously behind his tiny ears.

“All hacks in the back,” Tiny says, already steering his body into the back row. Frenchie climbs in next to him, makes a joke about there not being enough room in the seat for him. J. is pressed between Dave and the young woman. She’s coming with them. Now he isn’t the only black person. J. is grateful. If anything goes down in this cannibal region, he thinks, she will send word, and the story of J.’s martyrdom will live on in black fable.

”You’re not coming?” Dave asks Lawrence, his hand on the door.

“I have my own car,” he says.

“Big shot,” Tiny mumbles as the van starts.

The chatter of the junketeers fills the van. They talk about who showed up at the party at the Fashion Café two weeks before and not one among them can remember what movie it promoted; about the night they attended the book party for the hot new memoir, something about a rough childhood, how they swooped down on the stack of review copies and the next day all ran into each other at the Strand bookstore, laughing at the coincidence, as they sold the review copies for cash. Tiny gloats over the money he gets for selling the cookbooks that arrive every day in his mailbox: The Art of Southern Indian Cuisine, Tuscany Delight, The Master Crepe. Tiny says, you can’t eat recipes.

The woman’s arm digs into J.’s side. She smiles an apology but does not speak. Maybe he’ll talk to her at the dinner, so what brings you down here from the big city? How did I know? I could tell. J. closes his eyes to gather himself for the next few hours. Shut down for a bit before whatever god awful festivities are ahead of him. His stomach chews on itself loudly and he hopes that no one else hears it. Then he hears honking and the van lurches to the side. Peering through the windshield he sees the vehicle trying to run them off the road, the red pickup truck of his nightmares. So much depends upon a red pickup truck, filled with crackers. The pickup swerves in the lane parallel to them, dipping and zigging. The man in the passenger seat waves his pink fist out the window at them. Both drivers pounding their horns feverishly. “What the fuck is this! What the fuck is this!” Dave yells. They are being run off the road. Here it comes, J. thinks, this is how it goes down. The van capsized in a ditch. Open the door, I said open the damn door. What chew all doin’ ridin’ with nigruhs? We don’t abide no consortin’ with nigruhs in Summers County. Get out the car. Maybe one of his comrades puts up a little resistance against the taking of J. and the young lady. Then the ropes, the guns, the fire. The South will kill you.

“Slow down, slow down,” Frenchie says. “It’s all right.”

“Are you fucking crazy?” the young woman shrieks. J. thinking, now she speaks.

“No, it’s okay,” Dave reassures, pointing out the window. “It’s a friend of ours.” And indeed, J. sees, the man in the passenger seat is none other than One Eye, come in from the cold.

“You know these men?” the driver asks.

“Sure, just pull over,” Dave says. “It’ll only take a second.”

“You’re the boss,” the driver says, easing into the shoulder. The pickup pulls up in front of them and One Eye hops out, a scrambling, scarecrow figure with a short brown buzzcut. He is dressed like an idiot, with gray cloth trousers held up by red suspenders over a white striped shirt. A black eyepatch conceals his left eye.

One Eye removes his two black suitcases from the back of the pickup and offers a farewell to the man in the front seat before the red pickup takes off down the road. One Eye looks in the van and scrabbles into the passenger seat next to the driver, who shakes his head and frowns.

“What’s up, fellows?” One Eye says. “I saw Tiny’s fat fucking head in the window and knew it must be you.”

“You had your one eye peeled,” Tiny says.

“The great Cyclops,” Frenchie adds.

“My plane was late and my ride had already left,” One Eye explains. “So I hitched with Johnson there, figuring I’d catch up with you at the Millhouse.”

“You’re lucky Johnson had to run into town to buy some dry goods,” Dave chuckles. Dave Brown—what could you do with Dave Brown? It is inert, the name just lays there, as resistible as his prose. His name does not lend itself to nickname shenanigans, playful permutations.

“He was a nice guy,” One Eye says, cracking his knuckles. “More than I can say for you all. This is one sorry crew. No offense, ma’am, I’m not talking about you. Dave, of course, it wouldn’t be a junket without Dave. Being down South must bring back memories of being on tour with the Allman Brothers, huh? Yes, we all miss Duane, it was a terrible loss. Tiny, of course, thought he could wrassle up some alligator fritters. Sorry to burst your bubble, Tiny, but we’re a little north of weezie-ana. Frenchie, fuck you, I don’t know about you, but J., poor J., I had such high hopes for you.”

“He’s our inspiration,” Tiny pipes in.

“The great black hope,” Frenchie says.

“Exactly. I had such high hopes. New York, New York. Wine, women and pop songs. And I find you here.”

“He’s going for the record,” Dave offers.

“Tsk, tsk,” One Eye shaking his head. “You can’t see, but I’m making the station of the cross and praying for the soul of Bobby Figgis. Say it isn’t so, J.”

J., his name truncated to a single initial during childhood, does not need a nickname. “I’m on a jag,” he says. He is a little embarrassed about how all their bullshitting appears to the woman next to him.

“Nonstop since April,” Dave says, happy to be finally getting in his little digs before a proper audience. “Three-month bid.”

“Three months in,” One Eye says, taking stock, “Figgis was a wreck. You seem to be holding up.”

“Jag.”

“Hit an event every day,” Frenchie counters. “He’s going for the record.”

“How’s the book coming, Frenchie?” One Eye suddenly on J.’s side. If you wanted to shut Frenchie up, a quick rapier thrust to his ambition did the trick. Frenchie had spent his advance on clothes and lifestyle years before, without delivering word one of his manuscript, thus urging his comrades’ initial envy to curdle into warming superiority, and then well-timed derision. If he wanted sympathy he should have never written those Talk of the Towns for the New Yorker, a sure friendship-killer in the freelance world. Frenchie does not say anything; One Eye’s shiv dispatched him to the site of his more recent failure, to the bed he shared with his lost Italian model, her lost thighs.

One Eye had been blinded in a tragic ironic quotes accident a few years before. As he sat on a couch chatting with a publicist, a young freelancer stood above him, relating a droll tale of Manhattan mores as expressed in a new collection of short stories by that month’s photogenic young writer. The bartender yelled out last call for the open bar, and One Eye jumped up on instinct, just as the freelancer punctuated his clever description by forming air quotations with the index and forefingers of his hands. The point in question was apparently very ironic, requiring a vigorous expression of the ironic quotes. The force of the irony, coupled with One Eye’s eager and frantic upward movement, drove the freelancer’s pincer fingers deep into the junketeer’s eye socket.

J. reaches over and snaps One Eye’s suspenders. “Where did you dig this up?”

“This is my Huck Finn outfit. I’m trying to gain trust, blend in.”

“You look like an idiot.”

“I know.”

“Couldn’t miss this one, eh? Where are you coming from?”

“Florida. I was visiting my parents.”

“Okay time?”

“It’s Florida.”

“Figured you’d stop on down here for some more Southern hospitality.”

“I’m on a secret mission,” One Eye says. His good eye winks mysteriously. “A mission that could very well change the course of human events.”

“It’s hush-hush.”

“I’ll tell you about it later,” One Eye murmurs. He turns back to face the road. He isn’t kidding, J. thinks.

“I can’t wait to see Ben Vereen,” Tiny says.

“He canceled,” J. informs him.

“What, creative differences?”

“No, he’s sick,” J. says, and the van continues its approach to the Millhouse Inn.

The List possessed a will and function. It sensed a need for itself, for an assemblage of likely suspects to get the word out. A group of men and women who could be called upon in times of need, individuals of good character and savvy, individuals who understood the pitch of the times. And the pitch of the Times. The public needed to know about the things that were being created by capable interests, a hunger existed among the public for the word, all that was needed was a reliable system to get the information to them. The List recognized the faces of itself: they turned out in bad weather, tired and hungry, night after night. Sometimes the ones who came got the word out; other times they took a few hours’ reprieve from the chaos, a free meal and trinkets. The ultimate percentage was the thing that mattered, the unconquerable ratio of events covered to events not covered, that was the final concern.

The List pondered the faces of itself and reached out. The List kept abreast of the latest advances in information technology, contacting its charges by mail, later by fax, then email, whichever medium was most appropriate. The men and women on the List were astonished to find themselves contacted by email, having only just signed up for an email account a few days before and not having given their new email address to many people. They did not complain. It was convenient. If they wondered about the mechanism of the List, they kept their concern to themselves, or voiced it in low tones, during private moments. They feared expulsion. There had been a few cases of those who had abused the gift. One went mad. Another stopped filing and only showed up to eat from the banquet without giving in return. For the sin of not searching for outlets in which to deliver the word, this latter individual was deleted from the List and eventually became an editor. He looked at his colleagues from the outside, invited to only a fraction of the events he had been invited to before, and all remembered the look in his eyes.

The List was just. The List saw a discoloration on its person, watched as the discoloration described a face, and the face was added to the List. The faces the List plucked from its body were surprised. Some were new to the game, others old hands bitter for being overlooked for so long. Some appeared with much effort, others easy as pie. Some tried to figure out which event or article had been key, the one that blessed and graduated them, the one that had proved their worthiness. It was to no end. Shmoozers were passed over and the quiet diligent welcomed; the reverse was true just as often. It was inscrutable.

The List had been pushed from the earth by tectonic forces. The List possessed a specific gravity measurable by scientific instruments. The List contained weight and volume.

The List was aware of those in its charge. It knew if writers moved, switched from this newspaper to that magazine, if they died or retired, and updated itself accordingly. The men and women of the List were surprised at the promptness of the List’s readjustment, but only the first time. After that first time they were surprised at nothing. Contact names were updated with military precision. The publicity firm rolls were never obsolete. If a bouncer at a club quit, or went to jail, or moved to a different club, his replacement was noted and identified to eliminate possible embarrassment. The quirks and pet names of maître d’s at the popular restaurants were indexed. A harmony was achieved.

And the List rewarded the world. The percentage was maintained. Cover stories with witty headlines. Short and long reviews in the back of the book. Profiles of stars and magnates and web geniuses, insightful questions, silly questions, questions that begged still further questions, column inches adding up, fodder for the next iteration of the press packet. The public figure and the private citizen were rewarded. Those with dead careers walked among the living, resuscitated by a press release and attendant event at an appropriate venue. A financier who had done nothing real to speak of lately save collect interest threw a party to inform the public he was still alive. Around the Christmas shopping season a new gadget perched on a black pedestal, product of prodigious intellect, its virtues enumerated by those who had received it for free. The great ebb and flow of need, chronicled, subscribed to. A comeback. A meteoric rise. A next big thing, jostling for position in a year-end double issue. The reclusive author breaks her silence and grants interviews to justify her grandiose advance. The precocious upstart seen at the right parties. Behind the scenes at the award ceremony. The triumphant return. The inner life of. The secret world. The stories were told. There was a need. The List facilitated.

This inveigler of invites and slayer of crudités, this drink ticket fondler and slim tipper, open bar opportunist, master of vouchers, queue-jumping wrangler of receipts, goes by the name of J. Sutter, views the facade of the Millhouse Inn through reptilian eyes.

Is he supposed to take this place seriously? The walls of the rustic hotel and restaurant are obviously some factory concoction, J. sees that from yards away, the ridges and pocks identical from stone to stone. He can’t figure out what style its designers tried to effect, colonial flourishes abut antebellum wood columns, modern double-pane windows nestle in artificially weathered frames of molting paint. Nice attempt by the toddler ivy along the walls, but hell, he discerns the wire firming it in place. But the water wheel is the biggest atrocity. The fountain jets force water over slats that do not move, the spray energetic and process of no natural movement, splashing into a cement pool lousy with plastic lily pads floating moronically, congregating near the drainage grate. Snug up against a hill, this establishment totally new, intended to service the legions of tourists who will flock here now for John Henry Days. They hope. A hipster kid with more hooks in his face than some ancient, uncatchable fish, strutting down Soho in seventies’ bell-bottoms, has more period authenticity than this place. What is he doing here? He is going for the record, his works gurgling with slow, heavy fluids.

First things first when they hit the Social Room. Objective One: find a base of operations. Most of the tables had already been colonized by the other factions, but there is Frenchie tracking ahead, wading between chairs before the rest of them have finished taking stock of the room, on point, surveying, dithering a little between two tables to the far left of the podium before dropping his bag on one and motioning the other junketeers over. He nods to himself, second-guessing his choice, but no, this is it, this table is definitely it. As J. and the rest march to join him, they progress to Objective Two, libations, scanning the joint as they advance on their seats. Two bartenders barely out of their teens work their alchemy in a corner under ferns. John Henry Days employment largesse stealing labor from the fast food outlets, J. surmises. The junketeers take their seats and dispatch Tiny and Dave for drinks. A few citizens of Talcott and Hinton hover around the bar, but there is an opening on the left flank, a chink where Tiny or Dave might weasel in and dominate.

“I don’t see a cash register,” One Eye comments, sipping water.

“Me either,” J. seconds.

These are some real white people, J. thinks, looking around. These people go into hair salons armed with pictures of stars on CBS television shows and demand. He is out of his element. He discovers the food table on the other side of the room. Looks like salad to start. His stomach grumbles again but he decides he can wait until the boys come back with the drinks. Bit of a line anyway. J. notices that the woman in the van has chosen a different table. Probably a good choice to keep her distance.

The drinks arrive, dock, find berth in waiting palms. Frenchie sniffs, asks, “This Gordon’s or what?”

Tiny shakes his head. “No, tonight they’re breaking out the good stuff. I asked the guy if he had any moonshine and he just looked at me. Was that un-p.c. of me?”

“Obviously you haven’t heard of the great Talcott Moonshine War of Thirty-three,” One Eye says over the rim of his glass. “You’re stirring up old wounds.”

J. has forgotten that afternoon’s vomit incident but then he smells the gin. Bubbles break against his nose. He figures the ham sandwich he discovered in his suitcase has settled his stomach a bit. “Cheers,” he says. Everybody’s already drinking.

One Eye nods to the right, to an efficient-looking lady with a strong stride approaching their table, clipboard against her chest like armor. The handler. Can spot a handler a mile away, just as easily as she identified them. She introduces herself as Arlene. “I hope you had an easy trip out here,” she says, smiling.

Nods all around. Tiny belches. J. thinks she is smiling at him more than the others. “I left some brochures with the press packets at the hotel,” she says. “You should see what the county has to offer. Maybe you could include a little about the New River in your articles.”

“Articles?” Tiny says under his breath.

“I saw them,” Dave says, ever the appeaser when it came to the game. “Sounds like there’s a lot of nice things in these parts.”

In these parts. One Eye and J. look at each other: Dave is shameless.

“You should check it out if you get a chance,” Arlene advises, retreating from the table. “Well, you enjoy yourselves tonight; tomorrow is a big day. I see you’ve already made yourselves at home. If you have any questions, or if you’d like to talk to the mayor or one of the event planners, feel free to grab me at any time.” She departs, but not before smiling at J. again. Why was she smiling like that. Some kind of overcompensation for slavery or what? He leaves his seat to nab some salad, passing Lawrence on the way, who raises two fingers in greeting without breaking eye contact with the fellow he is talking to. The man is a pro.

It is a cafeteria salad, a Vegas all-you-can-eat salad, but J. doesn’t mind. He has a good feeling about the main course. He swipes a brown wooden bowl and tries to ration himself, judging the length of the buffet versus the capacity of the bowl (always this necessary consideration of cubic space), he catches a glimpse of celery up ahead and makes a note to save precious room.

“Haven’t these people ever heard of arugula?” Frenchie complains when he returns, looking a bit reticently at the fixings.

“Iceberg lettuce contains many important minerals,” J. says.

The conversation in the room cuts out and at the podium Arlene asks for everyone’s attention. She introduces Mayor Cliff and relinquishes the mike to a tall man with jagged gray hair and wolverine eyebrows. The skin of his face rough and sunken, eroded. Descended from railroad people, J. decides, he has timetable worry and collision fret in his genes. None of the other junketeers pay Cliff any mind; Dave is in the middle of an elaborate joke about a one-armed hooker.

The mayor says, “I’m glad you all came out here tonight to celebrate what our two towns have achieved in the past and what we will accomplish with this weekend.” Feedback curses the air and a chubby teenager scrambles to minister to the p.a. system. When the screech ends, Cliff thanks him and continues. “We’ve all been working hard these last few weeks and months, and I know I’m not the only one who’s glad that the day is finally here. My wife is very happy, I can tell you that. Charlotte—will you stand up? See that big grin on her face? That means no more 3 A.M. phone calls from Angel about her latest flower brainstorm. No more waking up to find Martin asleep on our doorstep with a report on the latest disaster.” A good part of the room chuckles in recognition. J. sighs. “Now it’s all paid off. So drink up, get some food and enjoy yourselves—you’ve earned it!”

Cliff takes a sip of water. “Some of you may have already heard that Ben Vereen will not be joining us tonight. I talked to his manager on the phone a few hours ago and he explained that while Mr. Vereen was very excited about coming down to Talcott, he was suffering from laryngitis and couldn’t possibly perform.” J. nibbles on a carrot and shakes his head. Laryngitis—probably resting after the vigorous and well-deserved ass-kicking he delivered upon his patently insane manager. “While this is a great blow—Mr. Vereen is an amazing performer loved the world over—we’ve arranged for some homegrown talent to appear after dinner. I won’t reveal his identity right now, but I know that some of you have heard him before and know he will not disappoint.” J. decides to tune him out. He doesn’t need to listen to this homespun rubbish; he has all weekend to gather material, what little he needs. Will he have to do actual research? Who is he kidding. But he could always use a quote or two to round things out. Nine hundred to twelve hundred words—the website editor said they hadn’t determined the average attention span of a web surfer, so they might trim his article if the next round of market research dictated. Twelve hundred words—he can excrete that modest sum in two hours no sweat, but a nice quote would spice it up. There is no need to listen tonight; he has two more days to badger some unsuspecting festival-goer into a colorful quote.