Полная версия

Полная версияThe Evolution of Photography

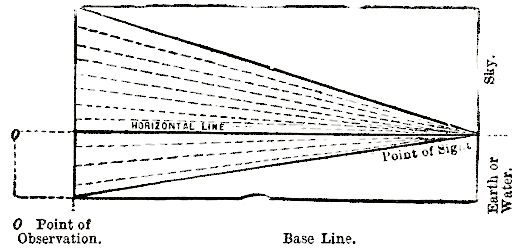

Pictorial backgrounds have usually been painted on the same principle as a landscape picture, and one of the earliest things the painter has to determine is, where he shall represent that line where the sky and earth appear to meet—technically, the horizontal line. This settled, all the lines, not vertical or horizontal in the picture, below this are made to appear to rise up to it, and those above descend, and if all these are in due proportion the perspective is correct, no matter whether this governing line is assumed to be in the upper, lower, or middle part of the picture. A painter can suppose this imaginary line to be at any height he pleases in his picture, and paint accordingly. In photography it is invariable, and is always on a level with the lens of the camera. To illustrate the relation of the horizontal line to the human figure, when a pictorial background is to be introduced, let us imagine that we are taking a portrait out-of-doors, with a free and open country behind the person standing for his carte-de-visite. The camera and the model are, as a matter of course, on the same level. Now focus the subject and observe the linear construction of the landscape background of nature. See how all the lines of the objects below the level of the lens run up to it, and the lines of the objects above run down to it. Right across the lens is the horizontal line, and the centre is the point of sight, where all the lines will appear to converge. Suppose the lens to be on a level with the face of the subject, the horizontal line of the picture produced on the ground glass will be as near as possible as high as the eyes of the subject. Trees and hills in the distance will be above, and the whole picture will be in harmony. This applies to interior views as well, but the ocular demonstration is not so conclusive, for the converging lines will be cut or stopped by the perpendicular wall forming the background. Nevertheless, all the converging lines that are visible will be seen to be on their way to the point of sight. Whether a natural background consisted of an interior, or comprised both—such as a portion of the wall of a room and a peep through a window on one side of the figure—the conditions would be exactly the same. All the lines above the lens must come down, and all that are below must go up. The following diagrams will illustrate this principle still more clearly.

Fig. 1.

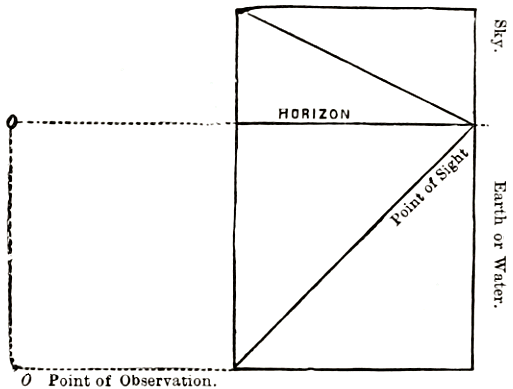

Fig. 2.

Fig. 1 is a section of the linear construction of a picture, and will show how the lines converge from the point of observation to the point of sight. Artists, in constructing a landscape of an ordinary form, allot to the sky generally about twice the space between the base and horizontal lines. But for portraits and groups, where the figures are of the greatest importance and nearer to the eye, the proportion of sky and earth is reversed, so as to give increased value to the principal figures, by making them apparently larger, and still preserving the proper relation between them and the horizontal line (see fig. 2). This diagram represents the conditions of a full-length carte portrait, where the governing horizontal line is on a level with the camera. If a pictorial background, painted in the usual way, with the horizontal line low in the picture, is now placed behind the sitter, the resulting photograph will be incongruous and offensive. It will be seen, on referring to fig. 2, that all the lines below the horizon must of necessity run up to it, no matter how high the horizontal line may be, for it is impossible to have two horizons in one picture; that is, a visible horizon in the landscape background, and an imaginary one for the figure, with the horizontal line of the background far below the head of the figure, and the head far up in the sky. The head of a human figure can only be seen so far above the horizontal line under certain conditions; such as being elevated above the observer by being mounted on horseback, standing on higher ground, or otherwise placed considerably above the base line, none of which conditions are present in a studio. Whenever the observed and observer are on the same level, as must be the case when a photographer is taking the portrait of a sitter in his studio, the head of the subject could not possibly be seen so high in the sky, if the lens included a natural background instead of a painted one. As, for convenience, the painted background is intended to take the place of a natural one, care should be taken that the linear and aerial perspectives should be as true to nature as possible, and in perfect harmony with the size of the figures. The lens registers, on the prepared plate, the relative proportions of natural objects as faithfully as the retina receives them through the eye, and if we wish to carry out the illusion of pictorial backgrounds correctly, we must have the linear construction of the picture, which is intended to represent nature, as true in every respect as nature is herself.

Aerial perspective has not been sufficiently attended to by the painters of pictorial backgrounds. There are many other subjects in connection with art and photography that might be discussed with advantage—such as composition, arrangement of accessories, size, form, character, and fitness of the things employed; but I leave all these for another opportunity, or to someone more able to handle the subjects. For the present, I am content to point out those errors that arise from neglecting true perspective, and while showing the cause, distinctively supply a remedy.

It is not the fault of perspective in the background where the lines are not in harmony with each other—these too frequently occur, and are easily detected—but it is the error of painting a pictorial background as if it were an independent picture, without reference to the conditions under which it is to be used. The conditions of perspective are determined by the situation of the lens and the sitter. If the actual objects existed behind the sitter, and were photographed simultaneously with the sitter, the same laws of perspective would govern the two. What I urge is, that if, instead of the objects, a representation of them be put behind the sitter, that representation be also a correct one. The laws of perspective teach how it may be made correctly, and the starting point is the position of the lens in relation to the sitter.

Some may say that these conditions of painting a background cannot be complied with, as the lens and sitter are never twice exactly in the same relation to each other. There is less force in this objection than at first appears. Each photographer uses the same lens for all his carte portraits—and pictorial backgrounds are very frequently used for these—and the height of his camera, as well as the distance from his sitter, are so nearly constant, that the small amount of errors thus caused need not be recognized. If the errors that exist were not far more grave, there would be no necessity for this paper. Exceptional pictures should have corresponding backgrounds.

When a “sitter” is photographed standing in front of a pictorial background, the photograph will represent him either standing in a natural scene, or before a badly-painted picture. Nobody should wittingly punish his sitter by doing the latter when he could do the former, and the first step to form the desirable illusion is pictorial truth. There is no reason why the backgrounds should not be painted truthfully and according to correct principles, for the one is as easy as the other. I daresay the reason is that artists have not intentionally done wrong—it would be too bad to suppose that—but they have treated the backgrounds as independent pictures, and it is for photographers to make what use of them they think proper. The real principles are, however, now stated, by which they can be painted so as to be more photographically useful, and artists and photographers have alike the key to pictorial truth.

In conclusion, I would suggest to photographers the necessity of studying nature more carefully—to observe her in their walks abroad, to notice the gradual decrease of objects both in size and distinctness, to remember that their lens is to their camera what their eye is to themselves, to give as faithful a transcript of nature as they possibly can, to watch the flow of nature’s lines, as well as natural light and shade, and, by a constant study and exhibition of truth and beauty in their works, make photography eventually the teacher of art, instead of art, as is now the case, being the reviler of photography.

PERSPECTIVE

To the EditorsGentlemen,—At the end of Mr. Alfred H. Wall’s reply to Mr. Carey Lea’s letter on Artists and Photographers, I notice that he cautions your readers not to receive the very simple rules of perspective laid down in my paper, entitled Errors in Pictorial Backgrounds, until they have acquired more information on the subject. Allow me to state that all I said on perspective in that paper only went to show that there should be but one horizon in the same picture; that the lines of all objects below that horizon should run up to it; that the lines of all objects above should run down, no matter where that one horizon was placed; and that the horizon of the landscape background should be in due relation to the sitter and on a level with the eye of the observer, the observer being either the lens or the painter.

If your correspondent considers that I was in error by laying down such plain and common sense rules, which everyone can see and judge for himself by looking down a street, then I freely admit that your correspondent knows a great deal more about false perspective than I do, or should like to do.

Again, if your correspondent cannot see why I “volunteered to instruct artists” or painters of backgrounds, perhaps he will allow me to inform him that I did so simply because background painters have hitherto supplied photographers with backgrounds totally unfit for use in the photographic studio.

In spite of Mr. Wall’s assumption of superior knowledge on subjects relating to art, I may still be able to give him a hint how to produce a pictorial background that will be much more natural, proportionate, and suitable for the use of photographers than any hitherto painted.

Let Mr. Wall, or any other background painter, go out with the camera and take a carte-de-visite portrait out-of-doors, placing the subject in any well-chosen and suitable natural scene, and photograph the “sitter” and the natural scene at the same time. Then bring the picture so obtained into his studio and enlarge it up to “life-size,” which he can easily do by the old-fashioned system of “squaring,” or, better still, by the aid of a magic lantern, and with the help of a sketch of the scene as well, to enable him to fill in correctly that part of the landscape concealed by the figure taken on the spot; so that, when reproduced by the photographer in his studio, he will have a representation of a natural scene, with everything seen in the background in correct perspective, and in natural proportions in relation to the “sitter.” This will also show how few objects can naturally be introduced into a landscape background; and if the distant scenery be misty and undefined, so much the better. It is the sharpness, hardness, and superabundance of subjects introduced into pictorial backgrounds generally that I object to, and endeavoured to point out in my paper; and I consider it no small compliment to have had my views on that part of my subject so emphatically endorsed by so good an authority as Mr. Wallis, in his remarks on backgrounds at the last meeting of the South London Photographic Society.

I make no pretensions to the title of “artist,” although I studied perspective, drawing from the flat and round, light and shade, and other things in connection with a branch of art which I abandoned many years ago for the more lucrative profession of a photographer. Were I so disposed, I could quote Reynolds, Burnett, and Ruskin as glibly as your correspondent; but I prefer putting my own views on any subject before my readers in language of my own.

I endeavour to be in all my words and actions thoroughly independent and consistent, which is more than I can say for your correspondent “A. H. W.” In proof of which, I should like to call the attention of your readers to a passage in his “Practical Art Hints,” in the last issue of The British Journal of Photography, where he says:—“It is perversion and degradation to an art like ours to make its truth and unity subservient to conventional tricks, shams, and mechanical dodges,” while at the last meeting of the South London Photographic Society, when speaking of backgrounds, he admitted they were all conventional.

Now, that is just what we do not want, and which was the chief object I had in view when I wrote my paper. We have had too many of those art-conventional backgrounds, and want something more in accordance with natural truth and the requirements of photography.

In conclusion, allow me to observe that I should be truly sorry were I to mislead anyone in the pursuit of knowledge relative to our profession, either artistically or photographically. But let it be borne in mind that it is admitted on all sides, and by the best authorities, that nearly all the pictorial backgrounds now in use are quite unnatural, and totally unsuited for the purposes for which they are intended. Therefore the paper I read will have done the good I intended, and answered the purpose for which it was written, if it has been the means of calling attention to such glaring defects and absurdities as are now being perpetrated by background painters, and bringing in their place more natural, truthful, and photographically useful backgrounds into the studios of all photographers.—I am, yours, &c.,

J. Werge.February 10th, 1866.

PERSPECTIVE IN BACKGROUNDS

To the EditorsGentlemen,—I must beg of you to allow me to reply to Mr. Wall once more, and for the last time, on this subject, especially as that gentleman expects an answer from me.

To put myself into a fair position with regard to Mr. Wall and your readers, I will reply to the latter part of his letter first, by stating that I endeavour to avoid all personality in this discussion, and should be sorry to descend to anything of the kind knowingly. When I spoke of “independency and consistency,” I had not in view anything relative to his private character, but simply that kind of independence which enables a man to trust to his own powers of utterance for the expression of his ideas, instead of that incessant quoting the language of others, to which your correspondent, Mr. Wall, is so prone. As to his inconsistency, I mean that tendency which he exhibits to advocate a principle at one time, and denounce it at another. I shall prove that presently. Towards Mr. Wall, personally, I have neither animosity nor pique, and would take him by the hand as freely and frankly as ever I did were I to meet him at this moment. With his actions as a private gentleman I have nothing to do. I look upon him now as a controvertist only. So far, I hope I have made myself clearly understood by Mr. Wall and all concerned.

I also should like to have had so important a question discussed without introducing so much of that frivolous smartness of style generally adopted by Mr. Wall. But, as he has introduced two would-be-funny similes, I beg to dispose of them before going into more serious matter. Taking the “butcher” first (see the fifth paragraph in Mr. Wall’s last letter), I should say that, if I were eating the meat, I should be able to judge of its quality, and know whether it was good or bad, in spite of all the butcher might say to the contrary; and surely, no man not an out-and-out vegetarian, or lacking one of the five senses—to say nothing of common sense—will admit that it is necessary to be a “butcher” to enable him to be a judge of good meat. On the same ground, I contend that it is not necessary for a man to be an artist to have a thorough knowledge of perspective; and I have known many artists who knew as little about perspective, practically, as their easel did. They had a vague and dreamy idea of some governing principles, but how to put those principles into practice they had not the slightest notion. I once met an artist who could not put a tesselated pavement into perspective, and yet he had some right to the title of artist, for he could draw and paint the human figure well. Perspective is based on geometrical principles, and can be as easily mastered by any man not an artist as the first book of Euclid, or the first four rules of arithmetic; and, for all that, it is astonishing how many artists know so little about the working rules of perspective.

Again: Mr. Wall is surely not prepared to advance the dictum that no one can know anything about art but a professional artist. If so, how does he reconcile that opinion with the fact of his great and oft-quoted authority, Ruskin, not being an artist, but simply, in his public character, a voluminous writer on art, not always right, as many artists and photographers very well know.

Mr. Wall objects to my use of the word “artist,” but he seems to have overlooked the fact that I used the quotation marks to show that I meant to apply it to the class of self-styled artists, or men who arrogate to themselves a title they do not merit—not such men as Landseer, Maclise, Faed, Philips, Millais, and others of, and not of, the “Forty.” Mr. Wall may be an artist. I do not say he is not. He also is, or was, a painter of backgrounds. So he can apply to himself whichever title he likes best; but whether he deserves either one or the other, depends on what he has done to merit the appellative.

Mr. Wall questions the accuracy of the principles I advocated in my paper. I contend that I am perfectly correct, and am the more astonished at Mr. Wall when I refer to vol. v., page 123, of the Photographic News. There I find, in an article bearing his own name, and entitled “The Technology of Art as Applied to Photography,” that he says:—

“If you make use of a painted cloth to represent an interior or out-door view, the horizontal line must be at somewhere about the height which your lens is most generally placed at, and the vanishing point nearly opposite the spot occupied by the camera. * * * * I have just said that the horizon of a landscape background and the vanishing point should be opposite the lens; I may, perhaps, for the sake of such operators as are not acquainted with perspective, explain why. The figure and the background are supposed to be taken at one and the same time, and the camera has the place of the spectator by whom they are taken. Now, suppose we have a real figure before a real landscape: if I look up at a figure I obtain one view of it, but if I look down on it, I get another and quite a different view, and the horizon of the natural landscape behind the figure is always exactly the height of my eye. To prove this, you may sit down before a window, and mark on the glass the height of the horizon; then rise, and, as you do so, you will find the horizon also rises, and is again exactly opposite your eye. A picture, then, in which the horizontal line of the background represents the spectator as looking up at the figure from a position near the base line, while the figure itself indicates that the same spectator is at that identical time standing with his eyes on a level with the figure’s breast or chin—such productions are evidently false to art, and untrue to nature. * * * * The general fault in the painted screens we see behind photographs arises from introducing too many objects.”

Now, as I advanced neither more nor less in my paper, why does Mr. Wall turn round and caution your readers not to receive such simple truths uttered by me? I was not aware that Mr. Wall had forestalled me in laying down such rules; for at that date I was in America, and did not see the News; but, on turning over the volume for 1861 the other day, since this discussion began, I there saw and read, with surprise, the above in his article on backgrounds. I am perfectly aware that I did not say all that I might have said on perspective in my paper; but the little I did say was true in principle, and answered my purpose.

When Mr. Wall (in the second paragraph of his last letter) speaks of the “principal visual ray going from the point of distance to the point of sight, and forming a right angle to the perspective plane,” it seems to me that he is not quite sure of the difference between the points of sight, distance, and observation, or of the relation and application of one to the other. However, his coming articles on perspective will settle that. It also appears to me that he has overlooked the fact that my diagrams were sections, showing the perspective inclination and declination of the lines of a parallelogram towards the point of sight. In my paper I said nothing about the point of distance; with that I had nothing to do, as it was not my purpose to go into all the dry details of perspective. But I emphatically deny that anything like a “bird’s eye view” of the figure could possibly be obtained by following any of the rules I laid down. In my paper I contended for the camera being placed on a level with the head of the sitter, and that would bring the line of the horizon in a pictorial background also as high as the head of the sitter. And if the horizon of the pictorial background were placed anywhere else, it would cause the apparent overlapping of two conditions of perspective in the resulting photograph. These were the errors I endeavoured to point out. I maintain that my views are perfectly correct, and can be proved by geometrical demonstration, and the highest artistic and scientific testimony.

I wish it to be clearly understood that I do not advocate the use of pictorial backgrounds, and think I pretty strongly denounced them; but if they must be used by photographers, either to please themselves or their customers, let them, for the credit of our profession, be as true to nature as possible.

I think I have now answered all the points worth considering in Mr. Wall’s letter, and with this I beg to decline any further correspondence on the subject.—I am, yours, &c.,

J. Werge.March 5th, 1866.

NOTES ON PICTURES IN THE NATIONAL GALLERY

In the following notes on some of the pictures in the National Gallery, it is not my intention to assume the character of an art-critic, but simply to record the impressions produced on the mind of a photographer while looking at the works of the great old masters, with the view of calling the attention of photographers and others interested in art-photography to a few of the pictures which exhibit, in a marked degree, the relation of the horizon to the principal figures.

During an examination of those grand old pictures, two questions naturally arise in the mind: What is conventionality in art? and—In whose works do we see it? The first question is easily answered by stating that it is a mode of treating pictorial subjects by established rule or custom, so as to obtain certain pictorial effects without taking into consideration whether such effects can be produced by natural combinations or not. In answer to the second question, it may be boldly stated that there is very little of it to be seen in the works of the best masters; and one cannot help exclaiming, “What close imitators of nature those grand old masters were!” In their works we never see that photographic eye-sore which may be called a binographic combination of two conditions of perspective, or the whereabouts of two horizons in the same picture.

The old masters were evidently content with natural combinations and effects for their backgrounds, and relied on the rendering of natural truths more than conventional falsehoods for the strength and beauty of their productions. Perhaps the simplest mode of illustrating this would be to proceed to a kind of photographic analysis of the pictures of the old masters, and see how far the study of their works will enable the photographer to determine what he should employ and what he should reject as pictorial backgrounds in the practice of photography. As a photographer, then—for it is the photographic application of art we have to consider—I will proceed to give my notes on pictures in the National Gallery, showing the importance of having the horizontal line in its proper relation to the sitter or figure.