Полная версия

Полная версияПолная версия:

The Diamond Pin

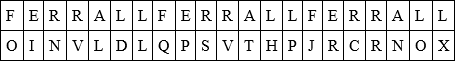

"we repeat the keyword over and over as may be necessary. Then we take the first letter, D, and find it in the line across the top of our alphabet square, and the letter under D, which is T we find in the left hand perpendicular line. Now trace the D line down, and the T line across, until the two meet, which gives us W. This would be the first letter of the cipher message if the key word were Darrel, and the message like our suggested one. But the first letter of the cipher we have to solve is O, and no possible amount of guessing can go any further unless we have the key word Mrs. Pell used to guide us. See?"

"Yes, I see," and Miss Darrel nodded her head. "It's most interesting. But, as the first letter of the cipher is O, why can't you find O in your alphabet and go ahead?"

"Because there are twenty-six O's in the square, and it needs the key word to tell which of the twenty-six we want."

"It's perplexing, but I see the plan," and Lucille studied the paper, "however, I doubt if I could make it out, even if I had the word."

"Oh, yes, you could, and if we get the dime and the receipt that was in the pocket-book we can try every word on them both, and I feel sure we'll get the answer. Now, since Pollock, or Young, rather, was so desirous of getting the pin, I argue that he had the necessary key word. Therefore we must get it from him, if we can't get it ourselves, and I doubt if he'll give it up willingly."

"Of course he has the key word," Iris said, "for he told me he could find the jewels and no one else could, if I'd hand over the pin. And he offered to go halves with me! The idea!"

"And yet, if he has the key word, and won't give it up, you can never find the jewels," observed Stone.

"You don't advise me to accept his offer, do you?"

"No; Miss Clyde, I certainly do not. But there is another phase of this matter, you know. If Charlie Young stole that paper from the pocket-book he was the one who attacked your aunt – "

"And Winston Bannard is in jail in his place! Oh, Mr. Stone, let the jewels be a secondary consideration, get Win freed and Charles Young accused of the murder – he must be the guilty man!"

"It looks that way," Stone mused; "and yet, Bannard admits he was here that Sunday morning, and had an interview with his aunt. May he not have obtained possession of the receipt – oh, don't look like that! Perhaps his aunt gave it to him willingly, perhaps she told him of its value – "

"Oh, no," cried Iris, "if all that had happened, Win would have told me. No; when he discovered that the receipt was left to him and was especially referred to in the will, he was amazed and disappointed to find that old pocket-book empty."

"He seemed to be," said Stone, but his manner gave no hint of accusation of Bannard's insincerity.

"Mr. Bannard, he ain't the murderer," declared Fibsy; "and that Young, he ain't neither. Because – how'd they get out?"

"How did the murderer get out, whoever he was?" countered Stone.

"He didn't," said the boy, simply.

It was soon after that, that Hughes came to Pellbrook to report progress.

"That Charlie Young," he said, "he's a queer dick."

"Will he talk?" asked Stone.

"Talk? Nothing but! He tells the most astonishing things. He vows he's in cahoots with Winston Bannard."

"That isn't true!" Iris cried out "Win isn't guilty himself, of course, but he isn't mixed up with a man like Charlie Young, either!"

"Young says," Hughes went on, "that the note asking for the pin is in Bannard's disguised writing. He says that Bannard put him up to kidnapping Miss Clyde and getting the pin from her so they two could get the jewels and – "

"What utter rubbish!" Iris said, disdainfully. "Do you mean that Mr. Bannard wanted to get the jewels away from me? And have both his share and my own? Ridiculous!"

"It seems, Miss Clyde," Hughes stated, "that Young has part of some directions or something like that, as to where to find the jewels; and he made it up with Bannard to get the pin, which he claims is a key to their hiding-place, and the two men were to share the loot."

"I never heard such absurdity!" Iris' eyes blazed with anger. "Mr. Stone, won't you go and interview this Young, and tell him he lies?"

"I'll assuredly interview him, Miss Clyde, but suppose Mr. Bannard did have that paper – that receipt – "

"He didn't! Why, if he had, why would he confer with that bad man? Why not by means of his paper, which is, you know, lawfully his, and my pin, which was bequeathed to me, why not, those two things are all that is necessary, find the jewels by their aid?"

"That's the point," Stone said. "It does seem as if Young possesses some information of importance."

"Well," Iris went on, angrily, "now they've got the two of them there, why can't you confront Winston with Young and let them tell the truth?"

"Perhaps they won't," Hughes put in, "you know, Miss Clyde, we didn't arrest Mr. Bannard without thinking there was enough evidence against him to warrant it."

"You did! That's just what you did! There wasn't any evidence – that is, none of importance! Mr. Stone, you don't think Win guilty, do you?"

Here Iris broke down, and shaking with convulsive sobs she let Lucille lead her from the room.

"Of course she's upset," Hughes said, with sympathy in his hard voice. "But she's got trouble ahead. I think she's in love with Winston Bannard – "

"Oh, do you!" chirped Fibsy, unable to control his sarcasm. "Why, what perspicaciousness you have got! And you are quite right, Mr. Hughes, Miss Clyde is so much in love with that suspect of yours that she can't think straight. Now, looky here, Mr. Bannard didn't kill his aunt."

"Is that so, Bub? Well, as Mr. Dooley says, your opinion is interestin' but not convincin'."

"All right, go ahead in your own blunderin' way! But how did Mr. Bannard get out of the locked room?"

"Always fall back on that, son! It's a fine climax where you don't know what to say next! I'll answer, as I always do, how did any other murderer get out of the room?"

"He didn't," said Fibsy.

"Oho! And is he in there yet?"

"Nope. But I can't waste any more time on you, friend Hughes, I've sumpthing to attend to. Mr. Stone, I'll go and get that dime now, shall I?"

"Go ahead, Fibs," Stone returned, absently, "and I'll go along with you, Hughes, and see if I can make anything out of your new prisoner."

Fibsy went first in search of Sam, and having found that defective-minded but sturdy-bodied lad, undertook to inform him as to their immediate occupation.

"See," and Fibsy showed Sam a dime, "you find me one like that in the grass, and I'll give you two of 'em!"

"Two – two for Sam!"

"Yes, three if you find one quick! Now, get busy."

Fibsy showed him how to search in the short grass of the well-kept lawn, and he himself went to work also, diligently seeking the dime Iris had flung out of the window in her irritation.

While Sam lacked intellect, he had a dogged perseverance, and he kept on grubbing about after Fibsy had become so weary and cramped that he was almost ready to postpone further search until afternoon.

They had pretty well scoured the area in which the flung coin would be likely to fall, and just as Fibsy sang out, "Give it up, Samivel, until this afternoon," the lad found it.

"Here's dime!" he cried, picking it from the grass. "Sammy find it all aloney!"

"Good for you, old chap! You're a trump! Hooray!"

"But give Sammy dimes – two – three dimes."

"You bet I will! Here – here are five dimes for Sammy!"

Eagerly the innocent received the coins, and scampered away, having no further interest in the one he had found.

Fibsy examined the dime, but could see no engraving on it, nor any letters other than those the United States Mint had put there.

The date was 1892, if that meant anything.

Carefully wrapping it in a bit of paper, Fibsy stowed it in his pocket and went into the house to await Fleming Stone's return.

And when Stone did return, it required no great discernment to see that he was dejected and discouraged.

He received the dime with a smile of hearty approval, but it was quickly followed by a reappearance of the distressed frown that betokened non-success.

"What's up, Mr. Stone?" Fibsy inquired.

"Not my luck," was the reply; "Fibs, we're up against it."

"Let her go! What's the answer?"

"Well, that Young is a hard nut to crack."

"Not for you, F. S."

"Yes, for me, or for anybody. He's got a perfect alibi."

"Always distrust the 'perfect alibi.' That's one of the first things you taught me, Mr. Stone."

"I know it, Fibs, but this alibi is unimpeachable."

"A peach of an alibi, hey?"

"That, indeed! You remember Joe Young, over at East Fallville?"

"Yes, sir, I do."

"Well, he says that his brother, Charlie Young, was at his house to dinner on that Sunday that Mrs. Pell was killed. He says Charlie arrived about half-past twelve, and he staid there until after four o'clock. Says they were together all that time. Now, that man Joe Young, is, I am sure, an honest man. Besides, his story is verified by his wife. Of course, Charlie Young declares he was at his brother's during those hours, and in the face of all the corroboration I can't disbelieve it. But, granting that alibi, who is left to suspect but Winston Bannard?"

"How'd Young catch onto all the pin and dime and receipt business, anyway?" asked Fibsy, with seeming irrelevance.

"I don't know, I'm sure."

"There's something back of that," and Fibsy wagged a sagacious nod.

"Maybe. But whatever's back of it may incriminate Young to the extent of trying to get the pin from Miss Clyde, perhaps even having stolen the receipt from Bannard, but it positively lets him out of any implication in the murder."

"Oh – I don't know."

"Why, child, if he was really at Joe Young's house from noon till four o'clock, how could he have been here at the time Mrs. Pell was killed?"

"He couldn't." Fibsy was taciturn, but his knitted brow told of deep thought.

"I got a hunch, Mr. Stone, that's all I can say for the minute – it mayn't be right, and then again it may, but – I got a hunch!"

"All right, Fibs, work it out your own way. But remember, that alibi stands. I can see a leak in a story as quickly as the next man, but that Joe Young is honest as the day, and his wife is too. And when they assert – we telephoned them, you know – when they assert that Charlie Young was there at that time, I believe he was."

"I believe it, too, Mr. Stone. Now, what about that dime?"

Fleming Stone took his strong magnifying-glass and studied the coin.

"Nothing on it, Fibs, except what belongs there. It might have been, as I hoped, that the keyword was one of these words that are stamped on, but I tried them all, any dime was all right for that. This particular ten-cent piece has no distinguishing characteristics that I can see. The date is of no help, I think, for unless I'm altogether wrong as to the type of cipher, figures are not usable. But I'll keep it safe until I'm sure it's no good."

"All right, Mr. Stone. Now, I guess I'll work on my hunch! Wanta help?"

"Yes, if it isn't beyond my power."

"Oh, come now," and Fibsy blushed scarlet at the realization that he had seemed to plume himself on his own cleverness, "but here's the way I'm goin' about it. Say I'm the murderer. Say that door's locked on this side." They were alone in Mrs. Pell's sitting room.

"Let's lock it, to help along the local color," suggested Stone, and he did so.

"Yes, sir. Now – but say, Mr. Stone, wait a minute. What became of those ropes?"

"Ropes?"

"Yes, that the murderer bound her ankles with and her wrists. Weren't we told that there were marks on her wrists and ankles where she'd been bound with ropes?"

"Yes, well, the murderer took those away with him."

"Did he 'bring 'em with him?"

"Probably."

"Then it wasn't Mr. Bannard. If he killed his aunt, which he didn't, he never came up here with a load of ropes and things! But never mind that, now. Say I'm the murderer. I've attacked the old lady and I've got the paper I wanted, and all that. Now, how do I get out!"

Fleming Stone watched the boy, fascinated. Absorbed in the spirit of his imagined predicament, Fibsy stood, his bright eyes darting about the room, as if really in search of a means of exit.

CHAPTER XVIII

SOLUTION AT LAST

"I am here," he muttered, "I have killed her, or, at least, she is dying – lying there on the floor, dying – I have to get out before the servants break in – I can't get out, there's no way I can get out. Mr. Stone, he didn't get out, because – "

"Because he wasn't in!" interrupted Fleming Stone, excitedly. "Oh, Fibs, do you see it that way too?"

"Sure I do! Fancy anybody untyin' a lot o' ropes, and freein' the lady and makin' a getaway, ropes and all, in two or three minutes, and besides, he couldn't get out!"

Fibsy stated this as triumphantly as if it were a new proposition. "The upset table," he went on, "the smashed lamp, with its long, green cord, the poor lady's dress open at the throat – "

"Yes," Stone nodded, eagerly, "yes, – and I daresay she had lace frills at her wrists and neck – "

"Of course she did! Oh, the plucky one!"

And then the two investigators put their heads together and reconstructed to their own satisfaction the whole scene of Mrs. Pell's tragic death.

"I'll go right over to see Young again," Stone said, at last, "and you skip around to see Mrs. Bowen; she'll tell you more than Miss Clyde can."

"Of course she will, and the dominie, too."

After a long argument, Fleming Stone persuaded Young that it would really be better for him to tell the truth, as to his movements on that fatal Sunday, than to persist in his falsehoods.

Stone did not tell the prisoner of his brother's confirmation of his unimpeachable alibi, but he told him that he was sure he did not murder Mrs. Pell.

"However," Stone said, "unless you tell the truth about her death, you will not only be suspected but convicted." And, finally, seeing it was his best hope, Young told his story.

"I went to the house about half-past eleven Sunday morning," he stated, "everybody had gone to church, and the old lady was there alone."

"What did you go for?"

"To get that receipt and the pin."

"Why those two things?"

"I had reason to think that they meant the discovery of her great hoard of jewels. I'm telling you all, for I want to prove that I not only did not kill the lady, but had no thought or intention of doing so."

"You took ropes along to tie her with?"

"Hardly that. I had some strong twine, as I thought she might prove fractious, and I was determined to get the pin and paper."

"How did you ever know about those things?"

"My uncle made the pin – engraved it, I mean. He was a marvelously expert engraver in the firm of Craig, Marsden & Co. After his death I came across a memorandum that gave away the secret. Not the solution of the cipher, exactly, he didn't know that himself. But a statement that he had engraved the pin for Mrs. Pell, and that, with the receipt for the work itself, it formed a direction as to where the jewels were hidden."

"And you demanded these things of her?"

"Yes, I told her the jewels belonged partly to my uncle."

"Did they?"

"No; not exactly, though Mrs. Pell had promised him some small stones, and I'm not sure she gave them to him."

"Go on, tell it all."

"I'm willing to, for my game is up, and I want to get away from a murder charge! My heavens, I'd never think of killing anybody!"

"Wait a minute, you say you reached the house about eleven-thirty. How did you come?"

"I was in my little car. I left that in the woodland road."

"And that's when Sam saw you."

"I suppose so. I didn't see him."

"Did you see Bannard?"

"I did. He was coming away from the house as I started toward it."

"He didn't see you?"

"No, I took good care of that."

"Then he did go away at nearly noon, and he was on his way down to New York when he stopped at the Red Fox Inn."

"Yes, his story is all true. I fixed up the Inn people to put it the other way, because I feared for my own skin."

"You are a fine specimen! Well, go on."

"Well, I was bound to get that pin. I asked Mrs. Pell for it, and she laughed. She wasn't a bit afraid of me. Plucky old thing! I had to tie her while I hunted around! She was ready to scratch my eyes out!"

"And you beat her – bruised her!"

"No more than I had to. She struggled like a wildcat."

"And you upset the table in your scrap?"

"We did not! Nor smash the lamp. Nor did I dash her to the floor. I'm telling you the exact truth, because there's so much seeming evidence against me that I'm playing safe. I searched all the room, and I found the paper, but I couldn't find the pin."

"You cut out her pocket?"

"I did, but I didn't tear open her gown at the throat, nor did I fling her to the floor to kill her on the fender. I finally untied her and went away, leaving her practically unharmed, save for a few bruises. Why, man, she was at dinner after that, with guests present."

"And where were you?"

"I went right over to my brother's – I suppose you won't believe this, you'll think he's standing by me to save my life – but it's true. I reached Joe's by half-past twelve, and I staid there till four or so. There was nobody more surprised than I to hear of Mrs. Pell's murder! I left that woman alive and well. The slight bruises were nothing, as is proved by her presence at the dinner table."

"I can't see why she didn't tell of your visit."

"She was a very peculiar woman. And she had it in for me! I think she felt that she could get me and punish me with more surety by biding her time till she could see her lawyer, or somebody like that. It seems to me in keeping with her peculiar disposition that she kept my attack on her a secret, until she chose to reveal it!"

"Mr. Young, I wouldn't believe this strange story of yours, but for your brother's statements and my absolute conviction of your brother's honesty. Both he and his wife tell a staightforward tale of your arrival and departure on that Sunday, which exactly coincides with your own. And there is other corroboration. Now, you are held here, as you know, for other reasons; kidnapping is a crime, and not a slight one, either."

"I know it, Mr. Stone, and I'll take my punishment for that, but I'm not guilty of murder. I was possessed to get hold of that pin. I planned clever schemes to get it, but they all went awry, and I became desperate. So, when I found a chance, I took it. I did Miss Clyde no real harm, and I was willing to go halves with her. The day I had two friends take her to my brother's house, he being away for the day, she was in no danger, and at but slight inconvenience. Flossie, as Miss Clyde will tell you herself, was neither rude nor ungracious."

"Never mind all that, now, give me the receipt."

Young hesitated, but a warning scowl from Stone persuaded him, and with a sigh he handed over what was without doubt the receipt in question.

"This is Winston Bannard's property," said the detective, "and you do well to give it up."

There was much to be done, but Fleming Stone was unable to resist the temptation to go home at once and work out the cryptogram, if possible, by the aid of the receipt.

The paper itself was merely a bill for the engraving on the pin. The price charged was five hundred dollars, and the bill was receipted by J. S. Ferrall, who, Young had said, was the man who did the engraving.

There were various words on the bill, both printed and written. Working with feverish intensity, Stone tried them one by one, and when he used the word Ferrall as a keyword, he found he had at last succeeded in his undertaking.

Beginning thus:

he pursued his course by finding F in his top alphabet line. Running downward until he struck O, he noted that was in the cross line beginning with J. J, therefore was the first letter of the message. Next he found E at the top, and traced that line down to I, which gave him E for his second letter. Going on thus, he soon had the full message, which read:

"Jewels all between L and M. Seek and ye shall find."This solved the cipher, but was far from being definite information.

In a conclave, all agreed that the message was as bewildering as the cipher itself.

Mr. Chapin could give no hint as to what was meant. Neither Iris nor Lucille Darrel could imagine what L and M stood for.

"Seems like a filing cabinet or card catalogue," suggested Stone, but Iris said her aunt had not owned such a thing.

"Well, we'll find them," Stone promised, "having this information, we'll somehow puzzle out the rest."

"Look in the dictionary or encyclopedia," put in Fibsy, who was scowling darkly in his efforts to think it out.

"You can't hide a lot of jewels in a book!" exclaimed Lucille.

"No; but there might be a paper there telling more."

However, no amount of search brought forth anything of the sort, and they all thought again.

"When were these old things hidden?" Fibsy asked suddenly.

"The receipt is dated ten years ago," said Stone, "of course that doesn't prove – "

"Where'd she live then?"

"Here," replied Iris. "But I've sometimes imagined that she took her jewels back to her old home in Maine to hide them. Hints she dropped now and then gave me that impression."

"Whereabouts in Maine?"

"In a village called Greendale."

"Her folks all live there?"

"I think her parents did – "

"What are their names? Did they begin with L or M?"

"No; both with E. They were Elmer and Emily, I think."

"Whoop! Whoop!" Fibsy sprang up in his excitement, and waved his arms triumphantly. "That's it! L and M means El and Em! Elmer and Emily!"

"Absurd!" scoffed Lucille, but Iris said, "You're right! Terence, you are right! That would be exactly like Aunt Ursula! And the jewels are buried between their two graves in the old Greendale cemetery! I dimly remember some things Auntie said, or sort of hinted at, that would just prove that very thing!"

"It sounds probable," Stone agreed, and Mr. Chapin said it was in his mind, too, that Mrs. Pell had hinted at Maine as her hoarding place, though he had partially forgotten it.

"But this is merely surmise," Stone reminded them, "and while it may be the truth, yet is it not possible that investigation will only give us further directions or more puzzles to work out?"

"It is not only possible but very probable," said Mr. Chapin. "I know my late client's character well enough to think that she made the discovery of her hoard just as difficult as she could. It was a queer twist in her brain that impelled her to play these fantastic tricks. Moreover, I can't think she would trust that fortune in gems to the lonely and unprotected earth of a cemetery."

"That's just what she would do," Iris insisted. "And really, what could be a safer hiding-place? Who would dream of digging between two old graves unless instructed to do so? And who could know of these secret and hidden instructions?"

"That's all so, Miss Clyde," Stone agreed with her. "I think it a marvellously well chosen place of concealment, and I am inclined to think the jewels themselves are there. But it may not be so. It may be we have further to look, more ciphers to solve. But, at least we are making progress. Now, who will make a trip to Maine?"

"Not I!" and Iris shook her head. "I care for the fortune, of course, but it is nothing to me beside the freedom of Mr. Bannard. I hope, Mr. Stone, that Charlie Young's confession of how he bruised and hurt poor Aunt Ursula proves Win's innocence and – "

"Not entirely, Miss Clyde. You see, we have his proof that Mr. Bannard left this house at half-past eleven, or just before Young arrived, but that won't satisfy the police that Mr. Bannard did not return at three o'clock or thereabouts."

"But he was on his way to New York then."