Полная версия:

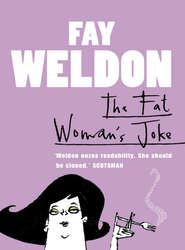

The Fat Woman’s Joke

‘I know nothing about the insides of cars,’ he now said, ‘except that whenever I buy a new one it goes for a day and then stops. After that it’s garages and guarantees and trouble until I wish I had bought a bicycle instead. I don’t even know why I buy cars. It just seems to happen. I think perhaps I was sold this one by one of my own advertisements. I am a suggestible person.’

‘You take things calmly,’ said Gerry. ‘If I bought a car which so much as faltered somebody’s head would roll.’

‘But you are a man of passions. I am a cerebral creature.’

‘It’s the British workman,’ said Gerry. ‘No amount of good design these days can counteract the criminal imbecility of the average British worker.’

‘Oh please Gerry darling,’ cried his wife. ‘No! My heart sinks when I hear those terrible words “these days” and “British workman”. I know it is going on for a full hour.’

‘A man buys a new car. It costs a lot of money. If it breaks down it is only courtesy to give the matter a little attention, Phyllis.’

He was pouring everyone extremely large drinks – everyone, that is, except his wife.

‘What about me?’ she piped, trembling. ‘I’se dry.’

Grudgingly he poured her a small drink, as a husband might pour one for an alcoholic wife. Phyllis very rarely drank to excess. For every bottle of Scotch her husband drank she would sip an inch or so of gin, on the principle that it would make her monthly period, which frequently bothered her, easier.

‘All this talk of cars,’ she said, emboldened by his kindness to her, ‘I hate it. Don’t you Esther? It’s such a bore.’

‘If you spend enough money on something, you can’t afford to think it’s a bore.’

‘Your wife,’ said Gerry, with a disparaging look towards his own, ‘is a highly intelligent woman.’

Esther wriggled, showing a little more thigh for his benefit. They all drank rather deeply.

‘Sometimes,’ said Alan, ‘I am afraid that Esther knows everything. At other times I am afraid she doesn’t.’

‘Why? Are you hiding something from her?’ asked Phyllis.

‘I have nothing to hide from my Esther.’

‘You hide your writing from me. Or try to. You lock it away.’

‘Writing?’ they cried. ‘Writing?’

‘Alan has been writing a novel in secret. He sent it off to an agent last week. Now we wait. It makes him bad-tempered. Don’t ask me what it’s about.’

‘What’s it like? Are we in it?’

‘No,’ said Alan shortly. ‘You are not.’

‘He’s the only one who’s in it,’ said Esther.

‘How do you know?’ he turned on her, fiercely.

‘I was only guessing,’ she said. ‘Or working from first principles. Why? Are you?’

He did not reply, and presently they lost interest. Phyllis enquired brightly about Peter.

‘He can’t concentrate on his school work,’ said Esther. ‘His sex life is too complicated. But I don’t think it makes any difference. He was born to pass exams and captain cricket teams. Failure is simply not in his nature.’

‘Peter sails unafraid and uncomplicated through life,’ said Alan. ‘We take little notice of him, and he takes none of us.’

‘Shall we eat,’ said Phyllis, who appreciated Peter as a boy but not as a son.

‘We’re still drinking,’ said her husband. ‘Give us a moment’s peace.’

‘I’m afraid the beef will be overcooked.’

‘Beef is sacred,’ said Alan, so they went in to the dining-room, where the William Morris wallpaper contrasted prettily with the plain black of the tablecloth and the white of the Rosenthal china.

They sat around the table.

‘Alan can’t stand grey beef. He likes it to be red and bloody in the middle. He goes rather far, I think, towards the naked, unashamed flesh. But there we are. Beef is a matter of taste, not absolute values. At least I hope so.’

‘Anyway, Gerry thinks if I cook something it is awful, and if you cook something it’s lovely, Esther, so why bother.’

‘I think you are a superb cook, Phyllis,’ lied Esther.

‘Or we wouldn’t come here,’ said Alan.

‘Personally, in this house I would rather drink than eat any day,’ said Gerry.

‘I wish you would stop being horrid to your wife, Gerry,’ said Esther, finally coming down on Phyllis’s side. ‘It makes her cross and everyone’s gastric juices go sour. Why don’t you just appreciate her?’

‘She’s quite right,’ said Alan. ‘Women are what their husbands expect them to be; no more and no less. The more you flatter them the more they thrive.’

‘On lies?’ enquired Gerry.

‘If need be.’

Esther was disturbed. ‘You are horrible,’ she said. ‘Can’t we just get on with dinner?’

Phyllis passed the mayonnaise, where artichoke hearts, flaked fish, olives and eggs lay immersed. The mayonnaise was perhaps too thin and too salty. They helped themselves, with all the appearance of enthusiasm.

‘It has been a hard day,’ said Gerry mournfully.

‘But rewarding?’

‘A new office block to do, if I’m lucky. A new world to conquer.’

‘And a new secretary,’ said his wife. ‘A luscious child, at least eighteen, and nubile for the last five years. Plump, biteable and ripe.’

‘Alan has a new secretary,’ said Esther. ‘I don’t know what she looks like. What does she look like, Alan? There she sits, day after day, part of your life but not of mine.’ Her voice was wistful.

‘She is slim like a willow. But she has curves here and there.’ The appreciation in her husband’s voice was not at all what Esther had bargained for.

‘Oh dear. And I’m so fat. No thanks, Phyllis darling, no more.’

‘I like you fat. I accept you fat. You are fat.’

‘Not too fat?’

‘Well perhaps,’ said Alan, ‘just a little too fat.’

‘Oh,’ moaned Esther, taken aback.

‘What’s the matter now?’

‘You’ve never said that to me before.’

‘You’ve never been as fat as this before.’

‘I’m so thin,’ complained Phyllis politely, ‘I can’t get fat. Do you like garlic bread?’

‘Superb.’

‘Well you can’t spoil that, at least,’ said Gerry.

‘More, Alan?’

‘Thank you.’

‘Do you think you should?’ asked Esther. ‘Every time I sew your jacket buttons on I have to use stronger and stronger thread.’

‘I admit your point. I am fat too. We are a horrid gross lot.’

‘Eat, drink and fornicate,’ boomed their host. ‘There is too much abstinence going on.’ His wife made apologetic faces at the guests.

‘If you are fat you die sooner,’ said Alan.

‘Who cares?’ asked his wife, but no one took any notice, so she said, ‘Tell me about your secretary, Alan. Besides being so slim, but curvacious with it, what is she like? Perhaps you wish she was me?’

‘What is the matter with you?’

‘It’s us,’ said Phyllis dismally. ‘Discontent is catching.’

‘I am not discontented. I just hope Alan isn’t. Who am I to compete with a secretary fresh from a charm school, with a light in her eye and life in her loins?’

‘Careful, Esther,’ said Gerry. ‘Those are Phil’s lines, to be spoken in a plaintive female whine and guaranteed to drive a man straight into a mistress’s arms.’

‘One wonders which comes first,’ she said, ‘the mistress or the female whine. It would be interesting to do a study.’

Alan decided to bring the table back to order.

‘You have no cause for concern whatsoever, Esther. To tell you the truth I can’t even remember her name. It is entirely forgettable. I think it is Susan. She can’t type to save herself. She is thin. She is temporary. I think she thinks she is not a typist by nature, but something far more mysterious and significant, but this is a normal delusion of temporary staff. She is in, I imagine, her early twenties. She keeps forgetting that I like plain chocolate biscuits, and dislike milk chocolate biscuits. Now you, Esther, never make mistakes like that. You have a clear notion of what is important in life. Namely money, comfort, food, order and stability.’

‘You make me sound just like my mother. Is that what you really think of me?’

‘No. I am merely trying to publicly affirm my faith in you, marriage and the established order, and to explain that I am content with my lot. I am a married man and I married of my own free will. I am a city man, and live in the city of my own free will. A company man, also of my own volition. So I should not be surprised to find myself, in middle-age, a middle-aged, married, company, city man – with no power in my muscles and precious little in my mind. Here in this sulphurous city I live and die, with as much peace and comfort as I can draw around me. Work, home, wife, child – this is my life and I am not aggrieved by it. I chose it. I know my place. I daresay I shall die as happy and fulfilled as most.’

‘It sounds perfectly horrible to me,’ said Esther. ‘However, I don’t take you seriously because you have just sent your magnum opus to a publisher, and I know you are quite convinced you will spend your declining years in an aura of esteem and respect and creative endeavour. I believe also that somewhere down inside you lurks a rich fantasy life in which you travel to exotic places, conquer mountains, do any number of noble and heroic deeds, save battalions singlehanded, and lay the world’s most beautiful women right and left. There may well be a more perverse and morbid side to this, but I would rather not go into it here. And you, Gerry, tell me, do you not ever wish to do extreme and fearful things? Is your masculinity entirely channelled into lustful thoughts of the opposite sex? Do you not want to burn, savage, torture, kill? Or at any rate, like Alan, failing that, are you not seized with the desire to break all the best glasses, miss the basin when you pee, burn the sheets with cigarette ends, leave smelly socks about for your wife to pick up –’

‘Women have their revenges too –’ said Alan. ‘They leave old sanitary towels around.’

Abruptly they all stopped talking. Alan crammed more garlic bread into his mouth. He bit upon a garlic clove and was obliged to spit it out. Everyone watched.

‘We all talk too much,’ said Esther to Phyllis in the kitchen a little later. ‘One has to be careful with words. Words turn probabilities into facts, and by sheer force of definition translate tendencies into habits. Our home isn’t half going to be messy from now on.’

When they returned to the kitchen with the second course, the murmur of men’s voices stopped abruptly.

‘What were you telling Alan to do?’ Phyllis asked her husband. ‘Go off with his secretary? For the sake of his red corpuscles?’

He did not reply, for this indeed had been the essence of his conversation.

‘Esther,’ was all Alan said, ‘we are going on a diet, you and I. We are going to fight back middle-age. Hand in hand, with a stiff upper lip and an aching midriff, we are going to push back the enemy.’

‘When?’ asked Esther in alarm, looking at the mountains of food on the table – the crackling hot pottery dishes of vegetables, the bowls of sauces, the great oval platter on which the bloody beef reposed. ‘Not now?’

‘Of course not,’ said Alan. ‘Tomorrow we start.’

‘New lives always begin tomorrow,’ said Phyllis. ‘Never now. That’s right, isn’t it, Gerry? Will you carve?’

Gerry sharpened the knife. It flashed to and fro under their noses. He carved.

‘We’re going to do it, Esther,’ said Alan, watching the food piling on her plate. ‘Look your last on all things lovely. We’ll take a stone off apiece.’

‘If you say so, darling,’ said Esther. ‘I’m all yours to command.’

‘Oh she’s a lovely woman,’ said Gerry.

‘You’ll never stick it,’ said Phyllis, jealously. ‘You’ll never be able to do it.’

‘Of course we will,’ said Esther. ‘If we want to, we will. And we want to.’

‘Doing without what you want is the hardest thing in the world,’ said Phyllis. ‘Isn’t it, Gerry?’

‘Incidentally,’ said Esther to Phyllis four weeks later, ‘there was too much salt in the mayonnaise that night, and too much in the gravy too. So we had to drink a lot. And the next day Alan and I had hangovers, and were cross and miserable even before we started our régime of abstinence.’

‘You didn’t say anything about too much salt at the time.’

‘One doesn’t. Or nobody would ever ask anyone to dinner any more. The middle classes would grind to a social halt. It wasn’t a bad meal, for once, in fact. Which was just as well, because it was the last we had for some time.’

‘After you two had gone,’ said Phyllis, ‘I went to sleep on the sofa. Gerry wouldn’t stop visiting his ex-wife every Saturday, and I was upset and angry, and I thought he’d been behaving badly all evening, anyway. But in the middle of the night he hauled me into bed – he’s much stronger than I am – and we were happy for a time. Until Saturday came again. Or at least he was happy. I’m not very good at that kind of thing. It’s the gesture I appreciate, not the thing itself. I think.’

‘And Alan and I went home and had cocoa and biscuits and went to sleep. We were tired. We’d been married, after all, for nearly twenty years.’

‘But you and Alan were always touching each other,’ said Phyllis, ‘like young lovers. As if even after all those years you couldn’t keep your hands off each other.’

‘And we meant it,’ said Esther crossly, ‘in public. It was just when we got home we found we were tired. Once you are beyond a certain age sex isn’t an instinct any more – it’s a social convention.’

‘Speak for yourself.’

‘I am sorry, but you feel sexy because you know it’s nice to feel sexy, not because you really are. Are you sure you wouldn’t like coffee?’

‘No,’ said Phyllis. Then she added, urgently, ‘Esther! Living here, alone, with no husband. No boyfriend. Surely you feel – at night –?’

‘No. I live by myself. Just me. Self-sufficient, wanting no one, no other mind, no other body. I live with the truth. I need no protection from it.’

‘Gerry and I,’ said Phyllis. ‘I am so miserable. We are chained together by our bed.’

‘That is your misfortune,’ said Esther, ‘and why you are so unhappy. Bed is a very difficult habit to break. Now let us continue with my story, because yours is very ordinary and I am not concerned with it. In the morning Alan kissed me goodbye – on the doorstep so the neighbours could see – and went to his office. He had had no breakfast. He was feeling desperate and hungover, but dieting seemed to him to be a rich and positive thing. Perhaps that was why, this particular morning, his secretary made such an impression on him, and he on his secretary.’

Susan and Brenda sat in the pub, conscious of their youth and beauty, which indeed shone like a beacon in a boozy, beery world, and Susan gave Brenda her more detailed account of a morning which Esther could only guess at.

‘The typing agency quite often send me to Norman, Zo-Hailey –’ said Susan, naming a large London advertising agency. ‘They always need temporary staff. Girls never stay long. They think it’s going to be glamorous and all they find is a lot of dull old research people plodding through statistics. Married ones, at that. And the pay’s bad, so they hand in their notice. And then again, if they do get to the livelier departments, it soon transpires that men in advertising agencies hardly count as men. What man worth his salt would spend his life sitting in an office selling other people’s goods, by proxy?’

‘Alan seems to have behaved like a man, from what you say.’

‘Alan was different. He was a creative person. Anyway they’re all quite good at pretending to be men. They know all the rules. Their bodies, even, work as if they were men, but on the whole they’re deceiving themselves and everyone else.’

‘Perhaps you and I are only pretending to be women. How could we tell?’

‘We are both flat-chested, it is true,’ said Susan, ‘and when I come to think of it, Alan had very pronounced nipples at the beginning of that fortnight. Almost what approached a bosom. It fascinated me. I had never encountered anything like it before. I began to wonder if I perhaps had lesbian tendencies.’

‘It sounds perfectly revolting.’

‘Not in the least. He has this thin face to counteract it. He was an important man at Zo’s. Everyone seemed to think I ought to be pleased to work for him but all I did was make rather more mistakes than usual. He never got irritated. He just used to sigh and raise his eyebrows at me as if I was a naughty child but he would forgive me. In the end I began to feel quite like a daughter to him. And when one’s father turns lascivious eyes upon one, that’s that, isn’t it? You get all stirred up inside. You begin to want to impress. You find yourself putting on make-up just to come to work. And he’d written this novel, and his agent rang up and raved about it, and I listened on the extension when I was getting the coffee in the outer office. I find there is something very erotic about literary men, don’t you?’

‘I really don’t know. I haven’t been in London long enough. Anyway, I thought you were supposed to be in love with William Macklesfield.’ William Macklesfield was the middle-aged poet who had been seen occasionally on the television, and with whom, on and off, Susan had been sleeping for years.

‘William and I are very close. We are best friends. We have a wonderful platonic relationship with sex lying, as it were, on top of it. But we are not in love. Not the kind of lightning love which suddenly flashes out of a clear sky and tumbles you on your back.’

‘Good heavens,’ said Brenda. ‘Things like that never happen to me.’

‘It’s your pillar-like legs,’ said Susan. ‘And your matriarchal destiny. Your time will come when you are sixty, surrounded by your grandchildren and bullying your sons. When I am an ageing drunken lush only fit for a mental home, then I daresay you will be glad that you are you and I am I. In the meantime I can fairly say that of the two of us, I have the more style.’

‘Thank you very much, I’m sure.’

‘Unless of course, I compromise, and marry. I might become a poet’s wife. But poets I find, are often rather dull. They are in the habit of expressing themselves through the written word, and not through their bodies. William is awful in bed.’

‘What does that mean?’ asked Brenda. ‘I thought it was the way a girl responded, not what the man did, that mattered. I never have any trouble. I always thought that girls saying men were bad in bed was just a way of making them feel nervous.’

‘Oh you,’ said Susan, ‘you should write a column in a woman’s magazine. I can see it happening yet.’

‘You were talking,’ said Brenda, devastated, ‘about this lightning stroke which flung you back upon your bed with your knees apart.’

‘I didn’t say with my knees apart. Nor did I mention bed.’

‘I thought it was what you meant.’

‘You are not at all open to forces, are you?’ said Susan. ‘You are an artifact. You are not swayed by passions like me. Anyway, there I was, working in this great throbbing organisation, beginning to fancy my boss, and his wife would ring up every day and ask what he wanted for dinner. He would take her so seriously, I couldn’t understand it. He would think and ponder, and sometimes he would ring her back later to give her a considered answer. It bespoke such intimacy. It drove me mad. She had such a soft, possessive voice. I wondered why he took so little notice of me. And why was there no one I could ring up, in the perfect security of knowing they would be home for dinner, come what may, and obliged to eat what I provided? William kept going back home to his wife for dinner and I found this most irritating. And why didn’t Alan’s wife ring up and ask him what did he want to do in bed that night, or something? Why was it always dinner? Poor man, I thought. Poor blind man. Here was I, young, clever and creative, with depths to plumb, able to take a constructive interest in what really interested him, sitting docile and waiting at his elbow, typing and all he’d do was let his eyes stray to my legs and back again. He was too busy telling his wife what he wanted for dinner. It was an insult to me. I wanted to ask about his novel but he seemed to want to keep it secret. He was so clever. Not just with words, but he loved painting, too. He used to be a painter before his wife got hold of him and destroyed him with boredom and responsibilities. Domesticity had him trapped. Can you imagine, he even kept family photographs on his desk!’

‘A commercial artist, do you mean?’

‘No, I do not. He went to art school. He married her very young, on impulse, and had to give up all thought of being a proper painter. She drove him into advertising, and he ended up a kind of co-ordinator of words and pictures. A man with a great deal of power over people of no consequence whatsoever, and a long title on the plate on his door. How bitter! He should never have let her do it to him. Brenda, do stop making eyes at that Siamese gentleman.’

‘He is not Siamese, I don’t think. But he is very handsome.’

‘I wonder why he seems to prefer you to me. Perhaps it’s his nationality. Do you want me to go on with this story?’

‘Yes.’

‘Then try and concentrate. The first time he actually laid hands on me was the day he started his diet, the day he heard from his agent.’

On the first morning of the diet pigeons chose to strut about the windowsill and embarrass Alan with their intimacies. There was a red carpet on the office floor; red curtains at the window. The standard lamp was grey, and so was the upholstery of the armchairs. His desk was large, sleek, new and empty, except for a list of the day’s engagements. He earned £6,000 a year and was not quite on the Board. It seemed doubtful, now, that he would ever get there. One younger, more energetic man had already used him as a footstool for a leap to Board level, and once a footstool, in Company terms, nearly always a footstool. And nothing would deter the pigeons.

Susan came in with a tray of coffee and biscuits. She wore a very short white skirt and a skimpy grey jersey.

‘Mr Sussman –’ said Susan, apologetically. She wore an enormous pair of spectacles. Her eyesight was normal, but the glasses combined frailty of flesh with aggression of spirit, and she enjoyed them. Alan sought for her features behind them. He was flushed after his telephone conversation with his agent.

‘I am really very sorry –’

‘Oh my God, what have you done now?’ He spoke amiably, as well may a man who has just achieved, he thinks, a lifelong ambition.

‘It’s just that I forgot about your biscuits again. I took the milk chocolate, not the plain. My gentleman friend always prefers milk, and I become confused.’

‘Your gentleman friend?’

‘How else would you have me describe him? My quasi-husband, my seducer, my lover, my fiancé? Take your pick. He is a poet.’

‘It is too unsettled a relationship that you describe,’ said Alan, ‘for my peace of mind. Secretaries, however temporary, should maintain the illusion of being either virgins or well-married. Otherwise the mind begins to envisage possibilities. The girl takes on flesh and blood. You are a bad secretary.’

‘I’m sorry about the biscuits.’

‘I was not talking about the biscuits, and well you know it. It does not matter about the biscuits. I am not eating the biscuits.’

‘Not eating the biscuits?’

‘No. And no sugar in the coffee.’

‘No sugar in the coffee?’

‘Stop playing the little girl. You are a grown woman. I am on a diet.’

‘Oh no!’

‘Why not? I’m too fat.’

‘People on diets become cross, bad-tempered. And desire fails. You are not too fat. Why do you want to be thin?’

‘I want to be young again.’

‘Why?’

‘Because when I was young I had hopes and aspirations and I liked the feeling.’

‘I think you are foolish. You don’t have to be young to achieve things. I like an older man myself.’

‘You do?’

‘Oh yes.’

‘All the same, take the biscuits away.’

‘I will keep them for William.’