Полная версия:

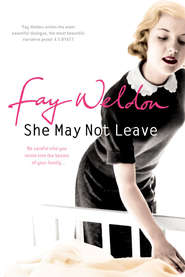

She May Not Leave

‘What has my Swedish father got to do with anything?’ asks Hattie. Martyn points out that a Swedish Prime Minister’s wife, a full-time working lawyer, was lately in trouble for employing a maid to clean their house. That she should do so was seen as demeaning to her, her husband and the maid. In Sweden, people are expected to clean up after themselves.

‘Now we, who are meant to be working for the New Jerusalem, are to have a servant?’ Martyn asks, ‘Where are our principles?’

Hattie almost giggles. Sometimes she thinks he is addressing a public meeting, not her, but he has a future as a politician so she forgives him: he has to get into practice.

‘She’s not a servant,’ says Hattie, firmly. ‘She is an au pair.

Or a nanny. I don’t know which she will prefer to be called.’ ‘Whatever – she will be doing our dirty work because we can afford to have her do it, and she can’t afford not to do it,’ says Martyn. ‘What’s that if not a servant? Get real, Hattie. By all means do what’s convenient, but understand what you’re doing.’

‘We are embarking on a fair and sensible division of labour,’ says Hattie haughtily, seeing that mirth will not distract him.

‘Have you thought about the consequences of being an employer?’ Martyn asks. ‘Are we doing it officially, paying for insurance stamps, taking tax at source and so on? I certainly hope so.’

‘If she’s working part-time and lives in, she doesn’t need stamps,’ says Hattie. ‘She counts as one of the family. I asked Babs.’

‘I assume you’ve seen her visa, and she’s entitled to be in this country?’

‘Agnieszka doesn’t need a visa. She’s from Poland,’ says Hattie. ‘We’re all Europeans now. We must be hospitable and do everything we can to make her welcome. It’s all rather exciting.’

She has a vague idea of Agnieszka as a simple farm girl, from a backward country, with a poor education, but welltrained by her mother in the traditional domestic arts. Hattie will be able to teach her, and enlighten her, and show her how forward-thinking people live.

‘I wouldn’t be too sure,’ says Martyn. ‘She’ll probably hate it here and leave within the week anyway.’

Both come from long lines of arguers and defenders of principle in the face of all opposition.

To The Left!

In 1897 Kitty’s great-great-great-great-grandfather, a musician, joined forces with Havelock Ellis the sexologist and wrote to the Archbishop of Canterbury urging him to acknowledge the entitlement of young women to free sex. He forthwith lost his job as Director of the Royal Academy of Music, and had to flee to San Francisco, but it was a sacrifice gladly made in the interest of early feminism and the onward march of humanity.

Kitty’s great-great-great-grandfather, a popular writer, went to the Soviet Union in the mid-thirties and came back to report a socialist and artistic paradise. Thereafter there was no stopping the left-footed march of the family, certainly on the female side.

When the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament began, Kitty’s great-great-grandmother Wanda walked from Aldermaston to London, her daughters Susan, Serena and Frances at her side. In 1968, Serena’s second husband George was arrested for his part in the Grosvenor Square demonstration against the Vietnam War. In the seventies Serena’s boys Oliver and Christopher put on balaclavas and threw aniseed balls over walls to distract guard dogs – though I can’t remember what that was about. Serena and George housed an anti-apartheid activist in their house in Caldicott Square. Susan’s children and grandchildren still turn up to march against the war in Iraq. It’s in the blood. Even Lallie signs petitions to save veal calves from export. Hattie has demonstrated against GM crops – that was probably the time she and Martyn met crammed up against one another in an alley. One way and another it is amazing that the world is not yet perfect. The forces of reaction must be strong indeed not to fall in the face of so much good feeling and hope for the future, over so many generations.

From Kitty’s father comes a different strain, a more orderly, stubborn, self-righteous kind of gene: oppressed and poor, the family rise up to demand their rights. Martyn, educated and sustained by the kindly State they have brought about, works as a commissioning editor for Devolution, a philosophical and cultural monthly. It runs articles about plenary targets, enablement, and the statistics of State control. These days Martyn feels he has the opportunity to change the world from the inside out, and no longer needs to go on demos, which are only for those who don’t know the inner story, as he does. He too is certain that he is helping the world towards a better future.

I wonder what Kitty will do with her life? If she takes after her father’s side, she will end up working for some NGO, I daresay, looking after the asbestos miners of Limpopo. If she favours her mother’s side, and all the mess and mayhem attendant on their particular talents, she will be a musician, a writer, a painter, or even a protesting playwright. You may think I’m obsessive about the gene thing, but I have watched it work out over generations. We are the sum of our ancestors and there is no escape. Baby Kitty looks at me with pre-conditioned eyes, even as she holds out her little arms and smiles.

Acceptance

Martyn cheers up, for no apparent reason, rolls the name around his tongue, and likes it. ‘Agnyeshh-kah,’ he says, savouring the syllables. ‘I suppose it is less gloomy than Agnes. And you’re quite right. It’s antisocial to have a room going spare at a time when there’s such a pressure upon housing. Tell you what, Hattie, I’m still hungry. Supposing I get some fish-and-chips?’

Hattie looks at him in no little alarm. Hasn’t he just eaten? Can he still be hungry? Is this why he wants the car keys? To buy fish and chips? A dozen thoughts flow through her mind, oddly disorganised. Fish fried in batter is unhealthy on many counts, not just for the individual but for the planet. Re-used oil has carcinogenic properties. The batter itself is fattening. The wheat used, unless organic, will have been sprayed many times with toxic chemicals. Batter can be removed before eating, true, but the seas are being denuded of fish and good citizens are cutting down on their consumption. And isn’t there something about dolphins? Don’t they get caught in the trawler nets and die horribly? Hattie seems to remember that though dolphins occasionally save swimmers from sharks, they also get a bad press these days: apparently the young males chase and gang-rape the females. On the other hand Martyn has often said that fish and chips remind him of his childhood in Newcastle and doesn’t she love him and want him to be happy?

‘You could get an Indian, I suppose,’ she concedes. ‘Though the District Nurse is against curry. It gets through into Kitty’s milk.’

From time to time Martyn goes into what Hattie calls ‘shaggy mode’: his sandy hair sticks up, the skin on his face seems too loose for its bones, his eyes are too large for their sockets. It happens when he is in despair but doesn’t know it. At such times Hattie feels both great affection and pity for him. She capitulates.

‘Oh all right,’ she says, ‘go out and get us some fish and chips.’

Agnieszka Comes Into Hattie’s Home

A week later and Agnieszka rings the doorbell of the little terrace house at 26 Pentridge Road. Hers are strong, practical hands, the skin rather blotchy and loose and much lined upon the palm. They are not her best feature. She is in her late twenties and wears a brown suede jacket, a knee-length black skirt and a white blouse. Her face is pleasant, broad, high-cheekboned, her demeanour quiet and restrained, her hair cut in a neat, thick, brown-to-mouse bob. Apart from the slightly sensuous air imparted by the short, full upper lip she seems to present no danger to marital harmony. She is far too serious for sexual hanky-panky.

The doorbell needs attention. There is a loose connection somewhere and the buzzer seems in danger of giving up completely. Agnieszka does not ring a second time but waits patiently for the door to open. She hears the sound of infant wailing growing nearer and Hattie opens the door. Hattie’s hair is uncombed and she is still in a blue velvet dressing-gown, with dribbles of porridge down the front and what looks like infant vomit on the shoulder. It needs to go in the washing machine.

Agnieszka holds out her arms for the baby, and Hattie hands the child over. Kitty is taken aback and stops crying, other than for a few more gulping sobs while she gets her breath back. She looks at Agnieszka and smiles divinely, revealing a tiny little pink tooth which Hattie sees for the first time. A tooth! A tooth! Agnieszka wraps the child more securely in its blanket and hands Hattie her bag to hold. Hattie takes it. It is a capacious black leather bag, old but well polished. Hattie thinks perhaps Kitty won’t like having her limbs constrained but Kitty doesn’t seem to mind. Indeed, Kitty exhales a deep breath of relief as if she had at last found her proper home, closes her eyes and goes to sleep.

Agnieszka follows Hattie through into the living room, and lays the baby on its side in the crib. She folds crumpled baby blankets neatly, holding them against her cheek to test for dampness, putting those that pass the test over the edge of the crib and gathering up the damp ones. ‘Where do we keep the laundry basket?’ she asks. Hattie stands gaping, and then points towards the bathroom. The ‘we’ is almost unendurably reassuring.

Hattie, dressing in the first-floor bedroom, catches a glimpse of Agnieszka in the landing bathroom, sorting the overflowing washing basket. Whites and coloureds, baby and non-baby. All get filed into plastic bags before being put back in the basket. Nothing overflows. Soiled nappies go into a covered pail.

Hattie remembers Martyn’s strictures about the necessity of checking references, but to do so would be insulting. She feels she is the one who should be giving references.

Agnieszka asks if she can see her room. Martyn has piled his suits onto the spare bed before setting out for work that morning, and Hattie has not yet found space for them elsewhere – she has had a bad morning with the baby. Agnieszka says she is satisfied with the accommodation, but perhaps she could have a small table to use as desk? Would Hattie like Kitty to sleep in her cot in the spare room with Agnieszka, or stay in the bedroom with her parents? She is sleeping through the night by now? Good. Then the former will be preferable, because then she, Agnieszka, can get Kitty up and dressed and having breakfast before Mr Martyn, as she already calls him, needs the bathroom. Early-morning routines are important, she says, if a household is to run smoothly. While Kitty sleeps she, Agnieszka, will get on with her studies.

Agnieszka now picks up and carries a chair to the front door, climbs on it, and does something to the wires that feed the bell. Hattie had never noticed those wires existed. It certainly has not occurred to her that the bell can be mended. Agnieszka tries the bell and lo! it rings firmly and clearly, no longer hesitant and hard to hear.

‘Don’t wake the baby,’ says Hattie. ‘Hush.’

‘It’s a good idea to get baby used to ordinary household sounds,’ says Agnieszka. ‘If Kitty knows what the sounds are about she won’t wake. Only unaccustomed noise wakes babies. I was told this in Lodz, where I studied child development for two years with the Ashoka Foundation, and it checks out.’

She gets down from the chair and replaces it in its original position, and takes the end of a damp cloth and removes a little wedge of encrusted baby food where it’s been stuck for some time.

Agnieszka tells Hattie that she is married to a screenwriter in Krakow, and plans to be a midwife, but must first perfect her English. Yes, it is difficult being away from her husband, whom she loves very much. She would like ten days off over the Christmas period to visit him, and her mother and her younger sister, who is not well. She is very close to her family. She produces photographs of all of them. The husband has a lean, dark, romantic face: the mother is dumpy and a little grim: the sister, who looks about sixteen, is fragile and sweet.

‘Ten days seems rather a short time,’ says Hattie. ‘Make it two weeks and we’ll manage somehow.’

Thus, without further argument or discussion, Agnieszka is engaged. But first she says she must put the damp washing into the machine. Plastic bags are invaluable for sorting laundry in an emergency, she says, but she will bring her own cotton ones for household use in future. Sorting prior to the wash makes sure mistakes are not made: white nappies do not pick up colour from black underpants, or cotton jerseys stretch in the boiling wash. Hattie might like to look into the local nappy laundry: this collection/delivery service can work out cheaper in electricity and soap powder than a home wash, and is less strain on the environment.

Still the baby sleeps, smiling gently. Hattie’s life slips into another, happier gear. While Agnieszka keeps an eye on the white wash – Agnieszka has put the machine on its ninetydegree cycle, she notices, something she, Hattie, never does in case the whole thing boils over and explodes, but Agnieszka is brave – she goes round the corner to the delicatessen, ignoring the common sense of the supermarket, and buys two large pots of their fake but convincing caviar, sour cream, blinis and champagne. She must stop being mean, rejecting and punishing. She can see this is what she has been doing. Not his fault the condom broke. She and Martyn will live happily ever after.

Frances Worries About Her Grand-daughter

I hope Hattie understands the complexities of having an au pair in the house. For one thing Hattie is not married, only partnered, which in itself is rash. ‘Partnerships’ between men and women, as everyone knows, are more fragile even than certificated marriages, and the children of such unions likely to be left without two resident parents. Any disturbance to the delicate balance is unwise. If introducing a dog or a cat into a marriage can be difficult, how much more so a young woman? Some kind of female rivalry is bound to ensue. And if it all goes wrong the decisions are the more painful. Who takes the dog, who takes the cat, who takes the au pair when couples split? Forget the children.

Martyn is a good enough boy in his terrier fashion, never willing to let go, and as a couple they are affectionate – I have seen them go hand in hand – and he is a responsible father, having read any number of guide books to parenthood, but I am left with the feeling that he has not yet arrived at his final emotional destination, and neither has Hattie, and that makes me uneasy.

They have their shared political principles to fall back upon, of course, and I hope it helps them. I am an upright enough person myself and a socially conscious one, and in my youth, once the wild years were over, kept the company of kaftanclad hippie girlfriends and bearded boyfriends with flares and sang along with Joni Mitchell. There was a time when all the men one knew in the creative classes had Zapata moustaches: it is difficult to know what a person with such a moustache is thinking or feeling, which may be why they were so popular.

That was in the sixties when women and men hopped in and out of each other’s beds with alacrity, trusting to luck and the contraceptive pill to save them from the consequences of broken hearts and broken lives, and before venereal diseases (now called STDs to remove the sting and shame) put a blight on the whole enterprise – herpes, Aids, chlamydia and so on – but I never urgently sought after righteousness or thought the world could be much improved by the application of Marxist theory.

In any case I had too little time or energy left over from successive emotional, artistic and domestic crises to concern myself with political theory. The creative gene is strong in the Hallsey-Coe family, and we tend to marry others like us, so lives of quiet respectability amongst them are rare. We end up writers, painters, musicians, dancers – not metallurgists, marine biologists or solicitors. In other words we end up poor, not rich.

Hattie, a linguist and a girl of high principle and political awareness, is fortunate enough to be born without a creative spark in her, though this can sometimes flare up quite late, and there may yet be trouble ahead. Serena did not start writing until she was in her mid-thirties: Lallie on the other hand was an infant prodigy, performing a Mozart flute concerto for her school when she was ten.

The Effects Of Bricks And Mortar On Lives

Let me tell you more about Hattie’s and Martyn’s house. Houses are not neutral places. They are the sum of their past inhabitants. It is typical of the English of the aspiring classes that they prefer to live in old places rather than new. They crawl into someone else’s recently abandoned shell and then proceed to ignore whoever it was who went before. Tell them they’re behaving like hermit crabs, and they raise their eyebrows.

Pentridge Road was built towards the end of the nineteenth century, rooming houses for the working classes, few of whom ever grew to optimum size or lived beyond fifty-five. The young couple see themselves as somehow set apart from the heritage of bricks and mortar in which they live. They feel they have sprung into existence ready-formed and into a brand new world, blessed with more wisdom and sophistication than their predecessors. Tell them they inherit not only the genes of their forebears but the walls and ceilings of those socially and historically related, and they look at you blankly.

Some things do happen which are an improvement – facts are certainly easier to come by in the twenty-first century than in the age of the printed page. News of the outside world flows like chlorinated water from radio and television: houses are better warmed and food cupboards more easily filled, but those who live in them are as much as ever at the mercy of employers and whatever rules of current cultural etiquette apply, whether it’s the obligation to fear God or to own an iPod.

Tear off the old wallpaper – as Hattie and Martyn did when they bought the house – and find yellowed scraps of newspaper beneath – accounts of the Match Girls’ Strike, the force ten gale which brought down the Tay Bridge, the costumes worn at Edward VII’s coronation. Hattie and Martyn scrape them all ruthlessly into the bin, scarcely bothering to read. I think the otherness of the past disturbs them too much: they like everything new and fresh and startagain.

The plaster walls are painted cream, not papered dark green and brown, and the paint at least does not poison you with lead – though traffic pollution may serve you worse. But very little changes in essence. Other generations lay in this same room at night and stared at the same ceiling worrying what the next day held.

In my sister Serena’s solid early-Victorian house in a country town, the stone stairs from the basement are worn down in the middle from the tread of countless servants, up and down, up and down. You’d think their tired breath would haunt the place but it doesn’t seem to. Serena’s mother-in-law died in the room where Serena now has her office but the fact only very occasionally affects her, though she claims her ghost walks on Christmas Eve. That is to say she once saw the old lady cross the passage from spare room to bathroom, and looking twice there was no one there. Her mother-in-law left a benign presence behind her, Serena claims. When I say, ‘But I have seen the ghost of the living Sebastian in his studio,’ she does not want to believe me. She likes to be the only one in touch with the paranormal. She isn’t.

I live in a small farmhouse which has been a dwelling for the last thousand years at least. The hamlet, outside Corsham in Wiltshire, is mentioned in the Domesday Book. Its occupant would have been fairly low down the social scale: a sub-tenant perhaps. Originally it was a single room for family, animals and servants. Then an outside staircase was built and a couple of rooms above. The families moved upstairs, the servants and animals stayed below. Outhouses were built: animals were separated out from servants. The original barn was long ago converted to a dwelling. A studio was built out the back where Sebastian now paints, in ghostly form, and I hope will again, less spectrally.

Sometimes I wake in the middle of the night, seized by the fear that he will behave like an ageing man after a heart operation, and try to change his life, and the change will include separating out from those that love him. It happened to Serena and it could happen to me. In these wakeful nights the house creaks and groans and sighs, from sheer age or from the spirits of those who went before, including pigs, horses, sheep, servants, forget the masters and mistresses. Oh believe me, we are not alone. The central heating gurgles like a mad thing at night.

But back to the young, the loving, the breeding and the present, that is to say Hattie and Martyn. Martyn, to give him credit, is more conscious of the past than many, if only as a contrast to the benign Utopia he and his friends hope to achieve. Martyn has explained to Hattie, as she sits trapped in her nursing chair (an antique, which Serena bought her as a present) feeding Kitty, that the terrace house they live in – two up, two down – was designed for the wave of Irish navvies brought in to complete the earthworks for the great London stations which served the manufacturing North, the land of his roots. St Pancras, King’s Cross, Euston, Marylebone – every shovelful of earth and rock had to be moved by hand, and now forms Primrose Hill.

Hattie would like to live somewhere larger, even if less historical, but they cannot afford it and in any case, says Martyn, they should be grateful for what they have.

The navvies lived six to a room in what is now home for two grown-ups, one baby and now the maid. There is still an old coal fireplace in the top back bedroom where once, over coals scavenged from the King’s Cross mustering yards, meat and potatoes were cooked. A puny extension for the kitchen and bathroom was built in the 1930s and takes up nearly all the sunless yard. Agnieszka is to have the small back bedroom, next door to the one where currently Martyn, Hattie and Kitty sleep.

There is gas-fired central heating but the gas comes from under the North Sea and no longer from the coal mines. It’s cleaner, but it’s expensive and Martyn and Hattie dread the bills. Though at least everyone on the way from the oil rigs of the north to the man who reads the meter – or rather leaves his card and runs – is decently paid. Or so says Martyn. Martyn’s father, grandfather and great-grandfather fought for this prosperity and justice and achieved it. No one now who can’t afford a lottery ticket!

Martyn has recently been asked by his employers to write two articles explaining to a doubtful public that casinos are a good thing, bringing pleasure to the people, and he has, although he is not quite sure that he agrees. But he bites back argument as he writes. There is, as always, a case for both sides and it is not sensible to overturn too many apple carts in pursuit of a principle, this being a relativist age, and Hattie not earning, and so early in what he hopes eventually to be a parliamentary career.

Morality, as Hattie recently discovered, is a question of what one can afford. She can afford less than Martyn. Even so, putting the comforter in the baby’s mouth, plugging its distress, Hattie feels guilt. Guilt is to the soul as pain is to the body, a warning that harm is being done. Gender comparisons are odious, as Hattie would be the first to point out, but it is perhaps easier for men to override the emotion than it is for women.