Полная версия:

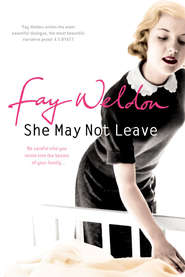

She May Not Leave

She May Not Leave

Fay Weldon

Table of Contents

Cover Page

Title Page

Martyn And Hattie Have Employed An Au Pair

Frances Presents Some Authorial Background

A Bit Iffy

Demotic Credentials

Sebastian In Prison

A Further Ethical Discussion After Supper

To The Left!

Acceptance

Agnieszka Comes Into Hattie’s Home

Frances Worries About Her Grand-daughter

The Effects Of Bricks And Mortar On Lives

Learned Characteristics

Martyn On The Way Home From Work

Martyn Comes Home To Agnieszka

Au Pairs We Have Known

Glossing Over Inconvenient Facts

Child Support

Martyn And Hattie Have A Tiff

Men, Women, Art, And Employment

George And Serena’s Household

Hattie At Work

A Good Au Pair And The Promise Of Life After Death

Preserving The Peace Of The Home

Dream On

Martyn Is Alone With Agnieszka

Another Country

Agnieszka And Martyn Go Shopping

Ordinary Women

Chocolate-Covered Prunes

Coming Over

Suspicions

Frances In Love

Agnieszka’s Passport

Animals

The Christening

Hurrying Men Away

The Boss Comes To Dinner

Cooking Disasters

Agnieszka And The Internet

Maternal Panics

Churchyard Drama

Mad Plans

Martyn Confesses

Hattie At The Cattery

Hattie Gets Promotion

Two Weddings And A Funeral

Martyn And Agnieszka In Bed

Two More Nights

Other Books By

Copyright

About The Publisher

Martyn And Hattie Have Employed An Au Pair

‘Agnieszka?’ asks Martyn. ‘Isn’t that far too long a name? If she wants to get on in this country she’ll have to shorten it. People are just not familiar with sshzk.’

‘But she won’t want to shorten it,’ says Hattie. ‘People have their pride, and a loyalty to the parents who named them.’ ‘If we pay her,’ says Martyn, ‘she may have to do more or less as we ask.’

Martyn is in conversation with Hattie in their economical, comfortable first-time-buyers’ house in London’s Kentish Town. Both are in their early thirties, handsome, healthy and educated, and for reasons of principle not lack of affection are not married but partnered. Baby Kitty, twenty-four weeks old, sleeps in her cot in the bedroom: Martyn and Hattie fear that she may not sleep for long. Martyn is just back from work. Hattie is ironing: she is unused to the task, and making a rotten job of it but she is, as ever, doing her best.

Hattie is my grandchild. I spent many years bringing her up and I am fond of her.

They have been talking about the possibility of employing an au pair, Agnieszka, recommended by Babs, a colleague of Hattie’s at Dinton & Seltz, Literary Agents. Hattie took maternity leave: now she wants to return to work, but Martyn is resistant. Not that he says so, but Hattie can tell because of his feeling that the girl’s name is too long. About Agnieszka they know very little, except that she has worked for Babs’s sister, the one with triplets, and left with good references.

In the circles in which Martyn and Hattie move as many babies are implanted as conceived, and so do often arrive in twos or threes. Kitty was an accident which served, after initial confusion and dismay, to make her the more precious to her parents. Fate had intervened, they felt, for the good. Man proposes, God disposes, and for once the result was satisfactory.

‘I don’t think it would be right to ask her to change her name on our account,’ says Hattie. ‘She might be offended.’ ‘I am not sure,’ says Martyn, ‘that we should define right as what does not offend.’

‘I don’t see why not,’ says Hattie. Her brow darkens as she comes to grips with what Martyn has just said. Surely not offending other people has a large part to play in what is defined as ‘right’? But since Kitty’s birth she is less sure than before about what is right and what is wrong. Her moral confidence is being eroded.

She can see it is ‘wrong’ to jam a comforter in baby Kitty’s mouth to stop the crying, as poorly educated mothers from the housing estates do. ‘Right’ would be searching for the cause of the crying and attending to that. If this is the case she chooses wrong over right at least five times a day. She can see she is also guilty of élitism, in not wanting to be numbered as one of the estate mothers. The family income may be currently below the national average, but even so the notion of her own superiority increasingly flits across her mind. Does she not read books about child-care, instead of waiting two weeks for the health visitor to turn up? Surely she is someone who controls her own destiny? But she has been so a-mush lately, so driven by hormonally based emotions, so much a prey to unaccustomed resentments and gratifications that she swings from conviction to doubt within minutes. She did wake this morning, leaning over to the crib beside the marital bed to put the comforter in Kitty’s mouth, with the comforting understanding that people are as moral as they can afford to be, no more nor less. She should not blame herself too much.

‘Then you should see why not,’ says Martyn. ‘Social justice can’t be achieved by simply letting everyone do what they want. A fox-hunter might well be offended if you pointed out that he was a cruel sadistic brute, but that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t say it. We should all be working towards the greatest good of the greatest number and sometimes hard words and tough choices must be made.’

‘How would telling someone to shorten their name further social justice?’ asks Hattie.

She feels mean and petulant; she knows she’s being obstructive, but if Martyn can be so can she. Hattie has already asked Agnieszka to come round for an interview but hasn’t told Martyn. She has not yet quite brought him round to the idea, though the arrival of the electricity bill and the community charge, both in the morning’s post, has had its effects. Hattie must go back to work. Really there is no choice.

‘For one thing,’ he says, ‘think of the delays while the name was spellchecked. Agnieszka Wyszynska! Computer operators all over the country will be at their wits’ end. It would be a simple kindness to others to simplify it.’

‘What to?’ asks Hattie. ‘What do you suggest?’

‘Agnes Wilson? Kay Sky? Short and simple and co-operative. She can always change it back when she goes home to Poland.’

‘I have no problem spelling Agnieszka Wyszynska. You just have to get used to certain combinations of consonants and realise “y” is a vowel. But then I studied modern languages and I’m not bad at spelling.’

Hattie is indeed good at spelling, but when she talks about Agnieszka’s pride she may well be talking about her own. People tend to invest others with their own qualities be they desirable or otherwise. The generous believe others will be similarly generous: the liar accuses the other of lying: the selfish see selfishness in everyone else. If Hattie declines to use Microsoft’s Spell-check, preferring to use her own judgement, or call her great-aunt the writer if in doubt, it is because she too has her pride. She has a highly developed superego. This may well be why she and Martyn, a man from the working-class North with high social principles and well-developed class-consciousness, are joined together in committed partnership, if not holy matrimony.

Hattie comes from the bohemian South, from a family for whom morality tends to concern itself with the integrity of a particular art form and the authenticity of emotion. It is a family in which Hattie’s particular temperament is seen as something of an anomaly. There is something rigorous and nonconformist about her which echoes the same tendencies in Martyn. In this she is unlike her mother Lallie the flute player, or her grandmother Frances who is married to an artist currently in prison, let alone like her great-aunt Serena, the well-known writer. Heaven knows through which genetic route ‘the responsible tendency’, as Frances refers to it, has come. It may well be from Hattie’s father Bengt, a schoolboy at the time of Hattie’s conception. But who is to say? Bengt was so quickly whisked off to Sweden by his parents for a new and better start in life, that the details of his character were never fully apparent to Lallie’s family. We could only watch and observe Hattie as she grew to find out what she would be like.

Bengt was to become a pharmacist in Uppsala and live quietly and decorously with a wife and three children, so with time it was assumed that he had left responsible, competent, if possibly rather priggish genes behind. The single brief act which resulted in Hattie occurred in what was known as the Tranquility Hut at the progressive and very expensive school the two young people attended.

Once a year, if Lallie can find a window in her busy international schedule, Bengt will bring his family over from Uppsala to visit her and Hattie, his ill-begotten daughter. Everyone is most courteous on these occasions but can’t wait to get back to normality, which is to forget any of it ever happened.

Hattie is polite to her father but cannot be very interested in him. She found out and filled in details of his medical history to the researchers at the hospital where she went for antenatal care, but could find nothing but good health and non-event to report. If Hattie didn’t resemble Bengt other than in a certain heaviness of jaw and brusqueness of temperament, she would have thought her mother had made a mistake and somebody quite other was responsible for her, Hattie’s, existence. Like the rest of her family Hattie does like things to happen. Bengt is, frankly, dull.

But since she had Kitty it’s the wrong kind of things which seem to happen. The district nurse, who calls regularly because Hattie has declined to join the weekly mothers’ and babies’ club, and this goes down on her notes, complains that the baby’s motions are too loose and accuses Hattie of eating garlic. Hattie has not eaten garlic since Kitty was born. The district nurse does not even ask but just assumes Hattie is the kind of mother who would. Is this how she seems to others? Irresponsible, biddable, and dumb?

‘Anyway,’ says Martyn now, ‘it’s all hypothetical. We don’t need, want, let alone can afford an au pair. Forget it. It’s just an idea of Babs’s. I know she’s your friend but she has an odd idea of how the world works.’

Martyn is not too keen on Babs as a friend for Hattie and not without reason. Babs is married to a Conservative MP and although Babs declares herself scornful of her husband Alastair’s political opinions, Martyn has a feeling that something political must surely rub off in the marital bed, and that perhaps some essence of the amended Babs could in turn be transferred to Hattie. He feels that he has already personally osmosed a lot of Hattie’s being by virtue of sharing a bed with her, and is happy enough about this. Why should he not? He loves her. They have the same outlook on life. The arrival of Kitty, half him and half her, has bonded their beings more closely still.

Hattie has no choice now but to tell Martyn the truth. Not only has she already spoken to Agnieszka of the too long name, but she has told Neil Renfrew, executive director of Dinton & Seltz, that she would like to come back to work within the month, having sorted out her child-care arrangements. Martyn and Hattie had decided to opt for a year’s leave of absence: now Hattie, unilaterally, has halved that. Neil has found a space for her in Contracts, working opposite Hilary in the Foreign Rights Department. Hattie has lost some seniority as a result of taking maternity leave but it’s not too bad. She should be back on career course within the year. Hattie reads and speaks French, German and Italian; she is suited to the job, and the job to her.

She would perhaps rather be working at the more literary end of the agenting business – it’s more fun: you go out to lunches and talk to writers – but at least in foreign rights you go to the Frankfurt Book Fair and deal with overseas publishers. Eastern Europe is an important and expanding market in which Hattie will need to be active. The job is going free since Colleen Kelly, who has become pregnant after five years of IVF, is stopping work early to write a novel. It has occurred to Hattie that Agnieszka will help her to learn Polish.

‘But you haven’t even met her,’ says Martyn now as Hattie reveals truth after irritating truth. ‘You have no idea what’s she’s like. She could be part of some international baby-theft ring.’

‘She sounded very nice on the phone,’ says Hattie. ‘Wellspoken, quiet and calm and not at all from the criminal fringes. Agnieszka looked after Alice’s triplets until they moved to France last month. And Alice told Babs that she was a gift from heaven.’

‘A gift to you, perhaps,’ says Martyn. ‘But what about Kitty? Do you really mean to compromise our baby’s future in this way? Research shows that babies with full-time mothers in their first year are at an advantage intellectually and emotionally.’

‘It depends which research report you read,’ says Hattie, ‘and sorry about this, but I do tend to believe the ones that suit me. She’ll be fine. We’re living on nothing, I have to ask you for money as if I were a child, we are unable to pay the community charge so I have no choice but to use child-care for Kitty. You’ve already told me I’m mad. What use is it to Kitty to have a mad mother?’

‘You’re being childish,’ says Martyn, with some truth. ‘And “mad” is not a very helpful word to use. Let’s say you have been a little disturbed lately. But what’s the point of my saying anything; you’ve jumped ahead and taken my approval for granted.’

He slams the fridge door a little harder than is necessary or desirable. Indeed, so hard does he slam the door, that the floor shakes and in the next room baby Kitty stirs and lets out a cry, before fortunately falling asleep again.

One of the unspoken rules of engagement in the battle for the moral high ground waged so assiduously by Hattie and Martyn is that the weapons of bad temper – bangings, crashings and shoutings – should not be used.

‘Sorry,’ he says now. ‘I haven’t had all that brilliant a day. I know I’ve more or less turned over Kitty’s care to you, and I’d so much hoped we could do fifty-fifty parenting, but that’s because I have to, not because I want to. All the same, you could at least have called me at the office and warned me.’ ‘I didn’t want Agnieszka to get away,’ says Hattie. ‘Someone like her can pick and choose. As a fully qualified nanny in Kensington she could get £500 a week and her own maid.’ ‘That is revolting,’ says Martyn.

‘But she wouldn’t be happy doing that. She’s a real homebody, Babs says. She prefers to live as family, work in a real home, halfway between au pair and nanny.’

‘She’d better make up her mind,’ says Martyn. ‘Au pairs are covered by strict guidelines: nannies are not.’

‘We’ll sort that out when the time comes,’ says Hattie. ‘I took to her on the phone. You can tell so much from people’s voices. Babs says she’s exactly right for us. She got such a good reference from Alice that Alastair said it sounded as if Alice was trying to get rid of the girl.’

‘Ah, the Tory MP. And was she?’ asks Martyn.

‘Trying to get rid of her? Of course not,’ says Hattie. ‘Alastair was joking.’

‘Funny sort of joke,’ says Martyn.

Martyn is still cross. His blood sugar is low after a day in the office. Obviously he is right; it is not ethical to exploit another in this way, especially if they have little power in the labour market, but it would be kinder to everyone if he left the matter alone.

He can find precious little in the fridge. Since Hattie took maternity leave they have not been able to afford dinners out, take-aways or luxuries from the delicatessen. Supper tends to be chops if he’s lucky, with potatoes and vegetables and that’s it, and served in Hattie’s own good time, not his. He finds some cheese in the salad drawer and nibbles at it, but it is very hard. Hattie says she is saving it for grating.

Martyn feels Hattie rather overdoes what he refers to as her ‘frugal number’. Anything will do at the moment to make life bleaker for both of them. She hates spending money on food. Food is full of pollutants which if she eats might end up in Kitty via the breast milk. Since the birth, it seems to Martyn, Hattie has gone into rejection mode. Sex also has become a rare event – rather than the four or five lively times a week it used to be. He can see it might be a good idea if she did go back to work, but he does not like her organising their joint life behind his back. He is Kitty’s parent too.

Frances Presents Some Authorial Background

Let me make clear who is speaking here, who it is who tells the tale of Hattie, Martyn and Agnieszka, reading their thoughts and judging their actions, offering them up for inspection. It is I, Frances Watt, aged seventy-two, née Hallsey-Coe, previously I think, but for a short time, Hammer: previously Lady Spargrove: previously – we would have got married but he died – O’Brien. I am Lallie’s bad mother, Hattie’s good grandmother – determined to get my money’s worth from my new laptop, bought for me by my sister Serena. Write, write, write I go, just like my sister. ‘Scribble, scribble!’ As the Duke of Gloucester said to Edward Gibbon, on receiving The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, a million and a half words long: ‘Always scribble, scribble, scribble! Eh! Mr Gibbon?’

Serena is the one with the reputation for writing: she has been writing steadily since she was thirty-odd, scarcely giving herself a minute’s time for reflection: she pays everyone – the household helps, the secretaries, taxi drivers, accountants, lawyers, the Inland Revenue, friends, grocers – just to make them go away so she can get on and write. But this doesn’t mean she has a monopoly on writing skill. I myself have finally found the time and courage to do it, while my husband Sebastian is in prison. The presence of a man in the house can be inhibiting to any endeavour which does not include him, such as writing a book. I run a little art gallery in Bath, but I choose not to open every day, so I have time and to spare.

Hattie, beloved only child of my only daughter Lallie, called me this evening to say she was going back to work, and had found an au pair for her baby, and Martyn was being a bit iffy about it. Is her return to work a good thing or not? What can I say? Speaking as the great-grandmother she has made me, she should sacrifice her life to the baby. Speaking as her grandmother, I want her to get back into the world and live a little and have affairs with men – life is for living, not just handing on. I am actually very fond of Martyn, but so far as I know he is only the second man she has been to bed with, and that does seem to me to be rather limiting.

Hattie will not settle easily to domesticity, that I do know. The Victorians used to pity girls like her, born too clever for their own good, never content as appendages to the Male – daughter, mother, sister, wife – forever striving for an identity which was theirs and theirs alone, whilst living in a society which forbade them to find it. Such girls made bad mothers and worse wives. That was the old world wisdom.

Martyn, I know, has romantic ideas about having a full-time wife and mother for his child, but I know he is being unrealistic. Couples today need two incomes to get by. And Hattie is bound to pay the new girl too much: she has her great-aunt Serena’s generosity but not the means to fund it. The guiltier the mother, the higher the au pair’s wages – or else it goes the other way and the mother, identifying, is furious that the girl expects any salary at all, let alone any free time, let alone boyfriends in the house. But Hattie will be the concerned kind, and that can come expensive.

My grand-daughter Hattie is thirty-three. She has a sharp nose, a square jaw, and a mass of striking red-gold Pre-Raphaelite hair, curly on some days, frizzy on others, which she keeps in a cloud around her face. I have the same hair, but mine has gone rather satisfactorily all-over white. It too is striking, and suits me. Hattie has very long legs: this she must get from her father, since her mother Lallie’s are rather short and plump of calf. Not that anyone has seen Bengt’s legs, other than Lallie (presumably) briefly, once, long ago and far away when Hattie was conceived. Lallie is a pouting, fleshy, sensuous beauty with a high colour, very different from her daughter’s lean, high-cheekboned, abstemious, long-fingered paleness. You would think from the look of them that the daughter, not the mother, would achieve world fame playing the flute but it is the other way round.

Hattie has what her great-aunt Serena calls ‘good bones’ and men can be guaranteed to turn and stare at her when she walks into a room: amazing what confidence this can give to a girl. But she is currently thin to the point of gauntness. The strain of looking after a new baby has told on her. Or perhaps it just is that some women do get pale and thin after having babies, just as some stay with the rounded pinkness of a good pregnancy. The body is wilful and usually goes the way a person very much hopes it won’t.

The trick with bodies, as with so much in life, is not to let the Fates know just how desperate you are about anything. You must look casual and act casually, play Grandmother’s Footsteps with life. Hattie and the cousins used to play it at Caldicott Square. One child stands in front of the group with her back turned. The others move forward stealthily. The one in front turns swiftly. Anyone who’s caught moving or giggling is out, and has to leave the game. So don’t move; don’t giggle; don’t show the Fates you care, and the less likely you are to develop a cold sore before the wedding, tonsillitis before the holiday, thrush before the dance, and your period won’t come on as you’re putting on your tennis skirt.

Hattie is really happy to be thinner than she was, but placates the Fates by saying aloud she doesn’t mind what size she is so long as she and Kitty are happy and healthy. Martyn – she likes to add – is certainly not one of those men who would be put off by a few extra pounds.

Likewise, Hattie does not show how she looks forward to going back to work, but murmurs to others that she might have to start earning again, since it’s such a problem managing on one salary. These sops thrown to destiny are working for the moment: she has got thin by sheer force of secret yearning, a job is waiting for her and now a kindly destiny has put Agnieszka her way. Hattie loves little Kitty, of course she does. Indeed, she is sometimes quite overwhelmed by love, and presses her face against the baby’s firm, soft, milky flesh, and thinks that is all she needs in life; but of course it is not. It’s just so dull at home. You listen to the radio, and struggle to stem a sea of disorder – the trouble with babies is that it’s all emergency: you keep having to stop whatever you’re doing. She craves gossip, infighting, the amphetamine effect of deadlines, and the swirling soap opera of office life. She misses conversation as much as her salary. Kitty lies around gurgling and disgorging the food that’s put into her and is not a valid source of entertainment, only of love, received and given. Songs and scriptures tell her that love is all she needs, but it is not true. Love is all she needs just for some of the time. So Martyn is being ‘a bit iffy’. I can imagine.