Полная версия

Полная версияПолная версия:

Trial of the Officers and Crew of the Privateer Savannah, on the Charge of Piracy, in the United States Circuit Court for the Southern District of New York

And that is the act, gentlemen, which, instead of being the act of desperadoes, pirates, and enemies of the human race, is recorded in history as an act of spirited freemen. You will remember that the act was done without any commission; it was done while these Provinces were Colonies of the British Crown; it was done long before the Declaration of Independence. The Act of the Provincial Congress, so far as that could have any validity, authorizing letters of marque, was not passed until afterwards, on the 23d of March. The Declaration of Independence was passed on the 4th July, 1776. According to the theory on the other side, call this lawful secession—call it revolution—call it what you please,—these Confederate States, as they are called, are not independent. They have not any Government—they cannot do any thing until their independence is acknowledged by the United States. Therefore, according to the theory of the other side, no act of the Provincial Congress, no act of any of the United Colonies, had any validity in it until the treaty of peace between them and Great Britain was signed, in 1783. But, I need not tell you, gentlemen, that in this country, in all public documents, in all public proceedings, in the decisions of our Courts, the actual establishment of the independence of the United States is dated as having been accomplished on the 4th July, 1776. All the state papers that run in the name and by the authority of the United States of America, run in their name, and by their authority, as of such a year of their independence, dating from the 4th July, 1776. Let me, therefore, show you what was done by the Colonies, in 1776, before and after the date of the Declaration of Independence; and let me show how many piracies our hardy seamen of those days must have committed, on the theory of the prosecution in this case. I read again from Cooper's Naval History:

"Some of the English accounts of this period state that near a hundred privateers had been fitted out of New England alone, in the two first years of the war; and the number of seamen in the service of the Crown, employed against the new States of America, was computed at 26,000.

"The Colonies obtained many important supplies, colonial as well as military, and even manufactured articles of ordinary use, by means of their captures,—scarce a day passing that vessels of greater or less value did not arrive in some one of the ports of their extensive coast. By a list published in the 'Remembrancer,' an English work of credit, it appears that 342 sail of English vessels had been taken by American cruisers, in 1776; of which number 44 were recaptured, 18 released, and 4 burned."

Well, gentlemen, with these facts staring you in the face, I ask you if it is not flying in the face of history—if it is not rejecting and trampling in the dust the glorious traditions of our own country—to be asked seriously to sit in that jury box and try these men for their lives, as pirates and enemies of the human race, on the state of things existing here? Gentlemen, my mind may be under a strong hallucination on the subject; but I cannot conceive the theory on which the prosecution can come into Court, on the state of things existing, and ask for a conviction. Remember that, in saying that, I am speaking as a Northern man,—for I am a Northern man; I am speaking as a subject and adherent to the Government of the Union; I am speaking as one who loves the flag of this country—as one who was born under it—as one who hopes to be permitted to die under it; and I am speaking with tears in my eyes, because I do not want to see that flag tarnished by a judicial murder, and by an act cowardly and dastardly, as I say it would be, if we are to treat these men as pirates, while we are engaged in a hand-to-hand conflict with them with arms in the field, and while they are asserting and maintaining the rights which we claimed for ourselves in former ages. In God's name, gentlemen, let us, if necessary, fight them; if we must have civil war, let us convince them, by the argument of arms, and by other arguments that we can bring to bear, that they are in the wrong; let us bring them back into the Union, and show them, when they get back, that they have made a great mistake; but do not let us tarnish the escutcheon of our country, and disgrace ourselves in the eyes of the civilized world, by treating this mighty subject, when States are meeting in mortal shock and conflict, with the ax and the halter. In God's name, let us have none of that!

I have but one word more to say, gentlemen, before I close. I have already said that we claim that this commission is an adequate protection, considering that this is an inter-state war. It has been so considered, and is now so considered by the Government of the United States itself, because, after the conflict had commenced and had gone on for some time, it being treated by the Government at Washington as a mere rebellion or insurrection by insurgent and rebellious citizens in some of the Southern States, it was found that it had assumed too mighty proportions to be treated in that way, and therefore, in the month of July last, the Congress then in session passed an Act, one of the recitals of which was that this state of things had broken out and still existed, and that the war was claimed to be waged under the authority of the governments of the States, and that the governments of the States did not repudiate the existence of that authority. Congress then proceeded to legislate upon the assumption of the fact that the war was carried on under the authority of the governments of the States. There is a distinct recognition by your own Government of the fact that this is an inter-state war, and that the enemies whom our brave troops are encountering in the field are led on under authority emanating from those who are rightfully and lawfully administering the Government of the States.

You will recollect, gentlemen, that in most of those States the State governments are the same as they were before this condition of things broke out. There has been no change in the State constitutions. In a great many of them there has been no change in the personnel of those administering the government. They are the recognized legitimate Governors of the States, whatever may be said of those claiming to administer the Government of the Confederate States.

But, gentlemen, let us pass from that, and let us suppose it was not a war carried on by authority of the States. It is, then, a civil war, and a civil war of immense and vast proportions; and the authorities are equally clear in that case, that, from the moment that a war of that kind exists, captures on land and at sea are to be treated as prizes of war, and prisoners treated as prisoners of war, and that the vocation of the ax and the halter are gone. I refer you to but a single authority on this subject, because I have already occupied more of your time than I had intended doing, and I have reason to be very grateful to you for the patience and attention with which you have listened to me in the extended remarks that I was obliged to make. I refer to Vattel, Book 3, cap. 18, secs. 287, 292 and 293:

"Sec. 287. It is a question very much debated whether a sovereign is bound to observe the common laws of war towards rebellious subjects who have openly taken up arms against him. A flatterer, or a Prince of cruel and arbitrary disposition, will immediately pronounce that the laws of war were not made for rebels, for whom no punishment can be too severe. Let us proceed more soberly, and reason from the incontestible principles above laid down."

The author then proceeds to enforce the duty of moderation towards mere rebels, and proceeds:

"Sec. 292. When a party is formed in a State who no longer obey the sovereign, and are possessed of sufficient strength to oppose him; or when, in a Republic, the nation is divided into two opposite factions, and both sides take up arms, this is called a civil war. Some writers confine this term to a just insurrection of the subjects against their sovereign to distinguish that lawful resistance from rebellion, which is an open and unjust resistance. But what appellation will they give to a war which arises in a Republic, torn by two factions, or, in a Monarchy, between two competitors for the Crown? Custom appropriates the term of civil war to every war between the members of one and the same political society. If it be between part of the citizens on the one side, and the sovereign with those who continue in obedience to him on the other, provided the malcontents have any reason for taking up arms, nothing further is required to entitle such disturbance to the name of civil war, and not that of rebellion. This latter term is applied only to such an insurrection against lawful authority as is void of all appearance of justice. The sovereign, indeed, never fails to bestow the appellation of rebels on all such of his subjects as openly resist him; but when the latter have acquired sufficient strength to give him effectual opposition, and to oblige him to carry on the war against them according to the established rules, he must necessarily submit to the use of the term civil war.

"Sec. 293. It is foreign to our purpose, in this place, to weigh the reasons which may authorize and justify a civil war; we have elsewhere treated of the cases wherein subjects may resist the sovereign. (Book 1, cap. 4.) Setting, therefore, the justice of the cause wholly out of the question, it only remains for us to consider the maxims which ought to be observed in a civil war, and to examine whether the sovereign, in particular, is on such an occasion bound to conform to the established laws of war.

"A civil war breaks the bonds of society and Government, or at least suspends their force and effect; it produces in the nation two independent parties, who consider each other as enemies, and acknowledge no common judge. Those two parties, therefore, must necessarily be considered as thenceforward constituting, at least for a time, two separate bodies—two distinct societies. Though one of the parties may have been to blame in breaking the unity of the State, and resisting the lawful authority, they are not the less divided in fact. Besides, who shall judge them? Who should pronounce on which side the right or the wrong lies? On each they have no common superior. They stand, therefore, in precisely the same predicament as two nations who engage in a contest, and, being unable to come to an agreement, have recourse to arms.

"This being the case, it is very evident that the common laws of war—those maxims of humanity, moderation and honor, which we have already detailed in the course of this work—ought to be observed by both parties in every civil war. For the same reasons which render the observance of those maxims a matter of obligation between State and State, it becomes equally and even more necessary in the unhappy circumstances of two incensed parties lacerating their common country. Should the sovereign conceive he has a right to hang up his prisoners as rebels, the opposite party will make reprisals; if he does not religiously observe the capitulations, and all other conventions made with his enemies, they will no longer rely on his word; should he burn and ravage, they will follow his example; the war will become cruel, horrible, and every day more destructive to the nation."

After noticing the cases of the Duc de Montpensier and Baron des Adrets, he continues:

"At length it became necessary to relinquish those pretensions to judicial authority over men who proved themselves capable of supporting their cause by force of arms, and to treat them not as criminals, but as enemies. Even the troops have often refused to serve in a war wherein the Prince exposed them to cruel reprisals. Officers who had the highest sense of honor, though ready to shed their blood on the field of battle for his service, have not thought it any part of their duty to run the hazard of an ignominious death. Whenever, therefore, a numerous body of men think they have a right to resist the sovereign, and feel themselves in a condition to appeal to the sword, the war ought to be carried on by the contending parties in the same manner as by two different nations, and they ought to leave open the same means for preventing its being carried into outrageous extremities and for the restoration of peace."

Now, gentlemen, can anything be more explicit on this subject, leaving out of view all questions of the authority of the States or of the Confederate Government to issue this commission? Can anything be more pointed or more direct on the question? Treat this as a mere civil war—treat it as though all State lines of the Union were obliterated, and as though this was a common people, actuated by some religious or political fanaticism, who had set themselves to cutting each others' throats—treat it as a purely civil strife, without any question of State sovereignty or State jurisdiction connected with it,—and still you have the authority of Vattel, an authority than which none can be higher, as the Court will tell you—and I could multiply authorities on that point from now until the shadows of night set in—that even in that case it is obligatory to observe the laws of war just the same as if it was a combat between two nations, instead of between two sections of the same people. Even if there was no commission whatever here, by any one having a color or pretence of right to issue it, but if those belonging to one set of combatants, in a civil strife which had reached the magnitude and proportions of which Vattel speaks, had set out to cruise, and had captured this vessel, I submit to you that it could not be treated as a case of piracy.

I have closed, gentlemen, the argument which, on opening the case, I have thought it necessary to advance in order that you may be able to apply the evidence. Every word that Vattel says there endorses the entreaty which I have made to you, as you love your country and as you love her prosperity, to view this case without passion and without prejudice created by the section in which you live, as I know and trust by your looks and indications that you will. And I say to you, gentlemen, that a greater stab could not be inflicted on our Government—not a greater wound could be given to the cause in which we all, in this section of the country, are enlisted—than to proclaim the doctrine that these cases are to be treated as cases for the halter, instead of as cases of prisoners of war between civilized people and nations. The very course of enlistment of troops for the war has been stopped in this city by that threat. As I said before, the officers and soldiers on the banks of the Potomac, if they could be appealed to on that question, would say, "For God's sake, leave this to the clash of arms, and to regular and legitimate warfare, and do not expose us to the double hazard of meeting death on the field, or meeting an ignominious death if we are captured." And as history has recorded what I have called your attention to as having occurred in the days of the Revolution, so history will record the events of the year and of the hour in which we are now enacting our little part in this mighty drama. The history of this day will be preserved. The history of your verdict will be preserved. You will carry the remembrance of your verdict when you go to your homes. It will come to you in the solemn and still hours of the night. It will come to you clothed in all the solemn importance which attaches to it, with the lives of twelve men hanging upon it, with the honor of your country at stake, with events which no one can foresee to spring from it. And I have only to reiterate the prayer, for our own sake and for the sake of the country, that God may inspire you to render a verdict which will redound to the honor of the country, and that will bring repose to your own consciences when you think of it, long after this present fitful fever of excitement shall have passed away.

DOCUMENTARY TESTIMONYMr. Brady, for the defence, put in evidence the following documents:

1. Preliminary Chart of Part of the sea-coast of Virginia, and Entrance to Chesapeake Bay.—Coast Survey Work, dated 1855.

2. The Constitution of Virginia, adopted June 29, 1776. It refers only to the western and northern boundaries of Virginia—Art. 21—but recognizes the Charter of 1609. That charter (Hemmings' Statutes, 1st vol., p. 88) gives to Virginia jurisdiction over all havens and ports, and all islands lying within 100 miles of the shores.

3. The Act to Ratify the Compact between Maryland and Virginia, passed January 3, 1786—to be found in the Revised Code of Virginia, page 53. It makes Chesapeake Bay, from the capes, entirely in Virginia.

Mr. Sullivan also put in evidence, from Putnam's Rebellion Record, the following documents:

1. Proclamation of the President of the United States, of 15th April, 1861. (See Appendix.)

2. Proclamation of the President, of 19th April, 1861, declaring a blockade. (See Appendix.)

3. Proclamation of 27th April, 1861, extending the blockade to the coasts of Virginia and North Carolina.

4. Proclamation of May 3d, for an additional military force of 42,034 men, and the increase of the regular army and navy.

5. The Secession Ordinance of South Carolina, dated Dec. 20, 1860.

Mr. Smith stated that, in regard to several of the documents, the prosecution objected to them,—not, however, as to any informality of proof. He supposed that the argument as to their relevancy might be reserved till the whole body of the testimony was in.

Judge Nelson: That is the view we take of it.

Mr. Brady suggested that the defence would furnish, to-morrow, a list of the documents which they desired to put in evidence.

The Court then, at half-past 4 P.M., adjourned to Friday, at 11 A.M.

THIRD DAY

Friday, Oct. 25, 1861.The Court met at 11 o'clock A.M.

Mr. Brady stated to the Court that two of the prisoners—Richard Palmer and Alexander Coid—were exceedingly ill, suffering from pulmonary consumption, and requested that they might be permitted to leave the court-room when they wished. It was not necessary that they should be present during all the proceedings.

Mr. Smith: It would be proper that the prisoners make the application.

Mr. Brady: They will remain in Court as long as they can; and will, of course, be present when the Court charges the Jury.

The Court directed the Marshal to provide a room for the prisoners to retire to, when they desired.

Mr. Sullivan: Before adjourning yesterday it was stated that the different ordinances of the seceded States were all considered in evidence without being read.

Mr. Smith: Are any of them later in date than the commission to the Savannah?

Mr. Sullivan: No, sir. Some States have seceded since the date of the commission, and have been received into the Confederacy.

Mr. Evarts: We will assume, until the contrary appears, that there are no documents of date later than the supposed authorization of the privateer.

Mr. Larocque: With this qualification,—that there are a great many documents from our own Government which recognize a state of facts existing anterior to those documents.

Mr. Sullivan read in evidence from page 10 of Putnam's Rebellion Record:

Letter from Secretary of War, John B. Floyd, to President James Buchanan, dated December 29, 1860.

President Buchanan's reply, dated December 31, 1860.

Also, from page 11 of Rebellion Record:

The Correspondence between the South Carolina Commissioners and the President of the United States.

[Considered as read.]

Also, referred to page 19 of Rebellion Record, for the Correspondence between Major Anderson and Governor Pickens, with reference to firing on the Star of the West.

Read Major Anderson's first letter (without date), copied from Charleston Courier, of Jan. 10, 1861. (See Appendix.)

Governor Pickens' reply, and second communication from Major Anderson. (See Appendix.)

Also, from page 29 of Rebellion Record, containing the sections of the Constitution of the Confederate States which differ from the Constitution of the United States.

Also, from page 31 of Rebellion Record: Inaugural of Jefferson Davis, as President of the Confederate States.

Also, page 36 of Rebellion Record: Inaugural of Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States, (for the passages, see Appendix.)

Also, page 61 of Rebellion Record: The President's Speech to the Virginia Commissioners. (See Appendix.)

Also, page 71 of Rebellion Record: Proclamation of Jefferson Davis, with reference to the letters of marque, dated 17th April, 1861.

Also, page 195 of Rebellion Record: An Act recognizing a state of war, by the Confederate Congress,—published May 6, 1861.

[Read Section 5.]

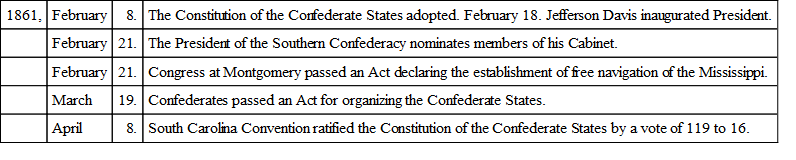

Mr. Lord read from pages 17, 19, and 20, of Diary of Rebellion Record, to give the date of certain events:

Mr. Sullivan: We propose now to introduce the papers found on board the Savannah when she was captured. The history of these papers is, that they were captured by the United States officers, taken from the Savannah, and come into our hands now, in Court, through the hands of the United States District Attorney, in whose possession they have been;—and they have been proceeded upon in the prize-court, for the condemnation of the Savannah. The first I read, is—

The Commission to the Savannah, dated 18th May, 1861.

Also, put in evidence, copy of Act recognizing the existence of war between the United States and the Confederate States, and concerning letters of marque,—approved May 6, 1861.

Also, read President Davis' Instructions to Private Armed Vessels,—appended to the Act.

Also, an Act regulating the sale of prizes, dated May 6, 1861,—approved May 14, 1861.

Also, an Act relative to prisoners of war, dated May 21, 1861.

Mr. Sullivan also read in evidence three extracts from the Message of President Lincoln to Congress, at Special Session of July 4, 1861. (See Appendix.)

Also, extracts from the Message of President Buchanan, at the opening of regular Session of Congress, December 3d, 1860. (See Appendix.)

Also, from page 245 of Rebellion Record: Proclamation of the Queen of Great Britain, dated May 13, 1861.

Mr. Evarts objected to this, on the ground that it could not have been received here prior to the date of the commission.

Objection overruled.

Also, from page 170 of Rebellion Record: Proclamation of the Emperor of France,—published June 11, 1861.

Also, the Articles of Capitulation of the Forts at the Hatteras Inlet, dated August 29th, on board the United States flagship Minnesota, off Hatteras Inlet.

Mr. Evarts remarked that this latter document was not within any propositions hitherto passed upon; but he did not desire to arrest the matter by any discussion, if their honors thought it should be received.

Judge Nelson: It may be received provisionally.

Mr. Brady also put in evidence the Charleston Daily Courier, of 11th June, 1861, containing a Judicial Advertisement,—a monition on the filing of a libel in the Admiralty Court of the Confederate States of America, for the South Carolina District, and an advertisement of the sale of the Joseph, she having been captured on the high seas by the armed schooner Savannah, under the command of T. Harrison Baker,—attested in the name of Judge Magrath, 6th June, 1861.

And containing, also, a judicial Act, relating to the administration of an estate in due course of law.

Mr. Brady stated that the reference was to show that they had a judicial system established under their own Government.

Lieutenant D. D. Tompkins recalled for the defence, and examined by Mr. Sullivan.

Q. State your knowledge as to the sending of any flags of truce while your vessel, the Harriet Lane, was lying at Fortress Monroe?

(Same objection; received provisionally.)