Полная версия

Полная версияOld Mortality, Complete

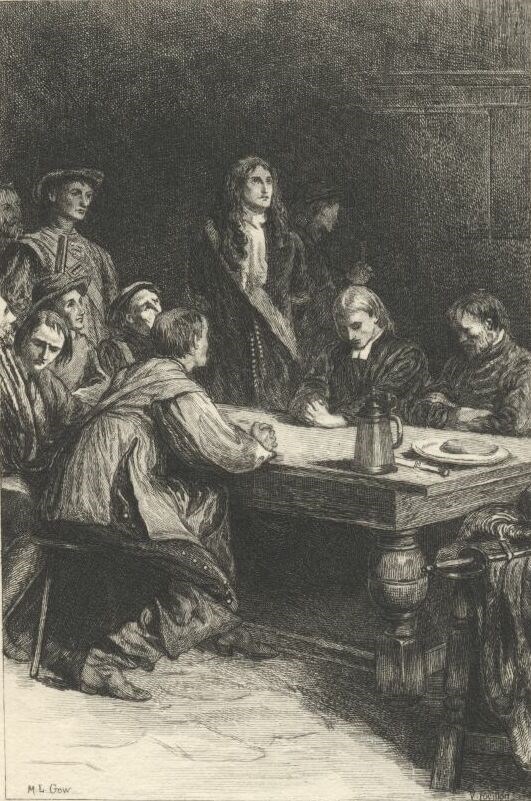

“Gentlemen,” said Morton, “if you mean to bear me down by clamour, and take my life without hearing me, it is perhaps a thing in your power; but you will sin before God and man by the commission of such a murder.”

“I say, hear the youth,” said Macbriar; “for Heaven knows our bowels have yearned for him, that he might be brought to see the truth, and exert his gifts in its defence. But he is blinded by his carnal knowledge, and has spurned the light when it blazed before him.”

Silence being obtained, Morton proceeded to assert the good faith which he had displayed in the treaty with Monmouth, and the active part he had borne in the subsequent action.

“I may not, gentlemen,” he said, “be fully able to go the lengths you desire, in assigning to those of my own religion the means of tyrannizing over others; but none shall go farther in asserting our own lawful freedom. And I must needs aver, that had others been of my mind in counsel, or disposed to stand by my side in battle, we should this evening, instead of being a defeated and discordant remnant, have sheathed our weapons in an useful and honourable peace, or brandished them triumphantly after a decisive victory.”

“He hath spoken the word,” said one of the assembly—“he hath avowed his carnal self-seeking and Erastianism; let him die the death!”

“Peace yet again,” said Macbriar, “for I will try him further.—Was it not by thy means that the malignant Evandale twice escaped from death and captivity? Was it not through thee that Miles Bellenden and his garrison of cut-throats were saved from the edge of the sword?”

“I am proud to say, that you have spoken the truth in both instances,” replied Morton.

“Lo! you see,” said Macbriar, “again hath his mouth spoken it.—And didst thou not do this for the sake of a Midianitish woman, one of the spawn of prelacy, a toy with which the arch-enemy’s trap is baited? Didst thou not do all this for the sake of Edith Bellenden?”

“You are incapable,” answered Morton, boldly, “of appreciating my feelings towards that young lady; but all that I have done I would have done had she never existed.”

“Thou art a hardy rebel to the truth,” said another dark-brow’d man; “and didst thou not so act, that, by conveying away the aged woman, Margaret Bellenden, and her grand-daughter, thou mightest thwart the wise and godly project of John Balfour of Burley for bringing forth to battle Basil Olifant, who had agreed to take the field if he were insured possession of these women’s worldly endowments?”

“I never heard of such a scheme,” said Morton, “and therefore I could not thwart it.—But does your religion permit you to take such uncreditable and immoral modes of recruiting?”

“Peace,” said Macbriar, somewhat disconcerted; “it is not for thee to instruct tender professors, or to construe Covenant obligations. For the rest, you have acknowledged enough of sin and sorrowful defection, to draw down defeat on a host, were it as numerous as the sands on the sea-shore. And it is our judgment, that we are not free to let you pass from us safe and in life, since Providence hath given you into our hands at the moment that we prayed with godly Joshua, saying, ‘What shall we say when Israel turneth their backs before their enemies?’—Then camest thou, delivered to us as it were by lot, that thou mightest sustain the punishment of one that hath wrought folly in Israel. Therefore, mark my words. This is the Sabbath, and our hand shall not be on thee to spill thy blood upon this day; but, when the twelfth hour shall strike, it is a token that thy time on earth hath run! Wherefore improve thy span, for it flitteth fast away.—Seize on the prisoner, brethren, and take his weapon.”

The command was so unexpectedly given, and so suddenly executed by those of the party who had gradually closed behind and around Morton, that he was overpowered, disarmed, and a horse-girth passed round his arms, before he could offer any effectual resistance. When this was accomplished, a dead and stern silence took place. The fanatics ranged themselves around a large oaken table, placing Morton amongst them bound and helpless, in such a manner as to be opposite to the clock which was to strike his knell. Food was placed before them, of which they offered their intended victim a share; but, it will readily be believed, he had little appetite. When this was removed, the party resumed their devotions. Macbriar, whose fierce zeal did not perhaps exclude some feelings of doubt and compunction, began to expostulate in prayer, as if to wring from the Deity a signal that the bloody sacrifice they proposed was an acceptable service. The eyes and ears of his hearers were anxiously strained, as if to gain some sight or sound which might be converted or wrested into a type of approbation, and ever and anon dark looks were turned on the dial-plate of the time-piece, to watch its progress towards the moment of execution.

Morton’s eye frequently took the same course, with the sad reflection, that there appeared no posibility of his life being expanded beyond the narrow segment which the index had yet to travel on the circle until it arrived at the fatal hour. Faith in his religion, with a constant unyielding principle of honour, and the sense of conscious innocence, enabled him to pass through this dreadful interval with less agitation than he himself could have expected, had the situation been prophesied to him. Yet there was a want of that eager and animating sense of right which supported him in similar circumstances, when in the power of Claverhouse. Then he was conscious, that, amid the spectators, were many who were lamenting his condition, and some who applauded his conduct. But now, among these pale-eyed and ferocious zealots, whose hardened brows were soon to be bent, not merely with indifference, but with triumph, upon his execution,—without a friend to speak a kindly word, or give a look either of sympathy or encouragement,—awaiting till the sword destined to slay him crept out of the scabbard gradually, and as it were by strawbreadths, and condemned to drink the bitterness of death drop by drop,—it is no wonder that his feelings were less composed than they had been on any former occasion of danger. His destined executioners, as he gazed around them, seemed to alter their forms and features, like spectres in a feverish dream; their figures became larger, and their faces more disturbed; and, as an excited imagination predominated over the realities which his eyes received, he could have thought himself surrounded rather by a band of demons than of human beings; the walls seemed to drop with blood, and the light tick of the clock thrilled on his ear with such loud, painful distinctness, as if each sound were the prick of a bodkin inflicted on the naked nerve of the organ.

It was with pain that he felt his mind wavering, while on the brink between this and the future world. He made a strong effort to compose himself to devotional exercises, and unequal, during that fearful strife of nature, to arrange his own thoughts into suitable expressions, he had, instinctively, recourse to the petition for deliverance and for composure of spirit which is to be found in the Book of Common Prayer of the Church of England. Macbriar, whose family were of that persuasion, instantly recognised the words, which the unfortunate prisoner pronounced half aloud.

“There lacked but this,” he said, his pale cheek kindling with resentment, “to root out my carnal reluctance to see his blood spilt. He is a prelatist, who has sought the camp under the disguise of an Erastian, and all, and more than all, that has been said of him must needs be verity. His blood be on his head, the deceiver!—let him go down to Tophet, with the ill-mumbled mass which he calls a prayer-book, in his right hand!”

“I take up my song against him!” exclaimed the maniac. “As the sun went back on the dial ten degrees for intimating the recovery of holy Hezekiah, so shall it now go forward, that the wicked may be taken away from among the people, and the Covenant established in its purity.”

He sprang to a chair with an attitude of frenzy, in order to anticipate the fatal moment by putting the index forward; and several of the party began to make ready their slaughter-weapons for immediate execution, when Mucklewrath’s hand was arrested by one of his companions.

“Hist!” he said—“I hear a distant noise.”

“It is the rushing of the brook over the pebbles,” said one.

“It is the sough of the wind among the bracken,” said another.

“It is the galloping of horse,” said Morton to himself, his sense of hearing rendered acute by the dreadful situation in which he stood; “God grant they may come as my deliverers!”

The noise approached rapidly, and became more and more distinct.

“It is horse,” cried Macbriar. “Look out and descry who they are.”

“The enemy are upon us!” cried one who had opened the window, in obedience to his order.

A thick trampling and loud voices were heard immediately round the house. Some rose to resist, and some to escape; the doors and windows were forced at once, and the red coats of the troopers appeared in the apartment.

“Have at the bloody rebels!—Remember Cornet Grahame!” was shouted on every side.

The lights were struck down, but the dubious glare of the fire enabled them to continue the fray. Several pistol-shots were fired; the whig who stood next to Morton received a shot as he was rising, stumbled against the prisoner, whom he bore down with his weight, and lay stretched above him a dying man. This accident probably saved Morton from the damage he might otherwise have received in so close a struggle, where fire-arms were discharged and sword-blows given for upwards of five minutes.

“Is the prisoner safe?” exclaimed the well-known voice of Claverhouse; “look about for him, and dispatch the whig dog who is groaning there.”

Both orders were executed. The groans of the wounded man were silenced by a thrust with a rapier, and Morton, disencumbered of his weight, was speedily raised and in the arms of the faithful Cuddie, who blubbered for joy when he found that the blood with which his master was covered had not flowed from his own veins. A whisper in Morton’s ear, while his trusty follower relieved him from his bonds, explained the secret of the very timely appearance of the soldiers.

“I fell into Claverhouse’s party when I was seeking for some o’ our ain folk to help ye out o’ the hands of the whigs, sae being atween the deil and the deep sea, I e’en thought it best to bring him on wi’ me, for he’ll be wearied wi’ felling folk the night, and the morn’s a new day, and Lord Evandale awes ye a day in ha’arst; and Monmouth gies quarter, the dragoons tell me, for the asking. Sae haud up your heart, an’ I’se warrant we’ll do a’ weel eneugh yet.”

[Note: NOTE TO CHAPTER XII. The principal incident of the foregoing Chapter was suggested by an occurrence of a similar kind, told me by a gentleman, now deceased, who held an important situation in the Excise, to which he had been raised by active and resolute exertions in an inferior department. When employed as a supervisor on the coast of Galloway, at a time when the immunities of the Isle of Man rendered smuggling almost universal in that district, this gentleman had the fortune to offend highly several of the leaders in the contraband trade, by his zeal in serving the revenue.

This rendered his situation a dangerous one, and, on more than one occasion, placed his life in jeopardy. At one time in particular, as he was riding after sunset on a summer evening, he came suddenly upon a gang of the most desperate smugglers in that part of the country. They surrounded him, without violence, but in such a manner as to show that it would be resorted to if he offered resistance, and gave him to understand he must spend the evening with them, since they had met so happily. The officer did not attempt opposition, but only asked leave to send a country lad to tell his wife and family that he should be detained later than he expected. As he had to charge the boy with this message in the presence of the smugglers, he could found no hope of deliverance from it, save what might arise from the sharpness of the lad’s observation, and the natural anxiety and affection of his wife. But if his errand should be delivered and received literally, as he was conscious the smugglers expected, it was likely that it might, by suspending alarm about his absence from home, postpone all search after him till it might be useless. Making a merit of necessity, therefore, he instructed and dispatched his messenger, and went with the contraband traders, with seeming willingness, to one of their ordinary haunts. He sat down at table with them, and they began to drink and indulge themselves in gross jokes, while, like Mirabel in the “Inconstant,” their prisoner had the heavy task of receiving their insolence as wit, answering their insults with good-humour, and withholding from them the opportunity which they sought of engaging him in a quarrel, that they might have a pretence for misusing him. He succeeded for some time, but soon became satisfied it was their purpose to murder him out-right, or else to beat him in such a manner as scarce to leave him with life. A regard for the sanctity of the Sabbath evening, which still oddly subsisted among these ferocious men, amidst their habitual violation of divine and social law, prevented their commencing their intended cruelty until the Sabbath should be terminated. They were sitting around their anxious prisoner, muttering to each other words of terrible import, and watching the index of a clock, which was shortly to strike the hour at which, in their apprehension, murder would become lawful, when their intended victim heard a distant rustling like the wind among withered leaves. It came nearer, and resembled the sound of a brook in flood chafing within its banks; it came nearer yet, and was plainly distinguished as the galloping of a party of horse. The absence of her husband, and the account given by the boy of the suspicious appearance of those with whom he had remained, had induced Mrs—to apply to the neighbouring town for a party of dragoons, who thus providentially arrived in time to save him from extreme violence, if not from actual destruction.]

CHAPTER XIII

Sound, sound the clarion, fill the fife!To all the sensual world proclaim,One crowded hour of glorious lifeIs worth an age without a name.Anonymous.When the desperate affray had ceased, Claverhouse commanded his soldiers to remove the dead bodies, to refresh themselves and their horses, and prepare for passing the night at the farm-house, and for marching early in the ensuing morning. He then turned his attention to Morton, and there was politeness, and even kindness, in the manner in which he addressed him.

“You would have saved yourself risk from both sides, Mr Morton, if you had honoured my counsel yesterday morning with some attention; but I respect your motives. You are a prisoner-of-war at the disposal of the king and council, but you shall be treated with no incivility; and I will be satisfied with your parole that you will not attempt an escape.”

When Morton had passed his word to that effect, Claverhouse bowed civilly, and, turning away from him, called for his sergeant-major.

“How many prisoners, Halliday, and how many killed?”

“Three killed in the house, sir, two cut down in the court, and one in the garden—six in all; four prisoners.”

“Armed or unarmed?” said Claverhouse.

“Three of them armed to the teeth,” answered Halliday; “one without arms—he seems to be a preacher.”

“Ay—the trumpeter to the long-ear’d rout, I suppose,” replied Claverhouse, glancing slightly round upon his victims, “I will talk with him tomorrow. Take the other three down to the yard, draw out two files, and fire upon them; and, d’ye hear, make a memorandum in the orderly book of three rebels taken in arms and shot, with the date and name of the place—Drumshinnel, I think, they call it.—Look after the preacher till to-morrow; as he was not armed, he must undergo a short examination. Or better, perhaps, take him before the Privy Council; I think they should relieve me of a share of this disgusting drudgery.—Let Mr Morton be civilly used, and see that the men look well after their horses; and let my groom wash Wild-blood’s shoulder with some vinegar, the saddle has touched him a little.”

All these various orders,—for life and death, the securing of his prisoners, and the washing his charger’s shoulder,—were given in the same unmoved and equable voice, of which no accent or tone intimated that the speaker considered one direction as of more importance than another.

The Cameronians, so lately about to be the willing agents of a bloody execution, were now themselves to undergo it. They seemed prepared alike for either extremity, nor did any of them show the least sign of fear, when ordered to leave the room for the purpose of meeting instant death. Their severe enthusiasm sustained them in that dreadful moment, and they departed with a firm look and in silence, excepting that one of them, as he left the apartment, looked Claverhouse full in the face, and pronounced, with a stern and steady voice,—“Mischief shall haunt the violent man!” to which Grahame only answered by a smile of contempt.

They had no sooner left the room than Claverhouse applied himself to some food, which one or two of his party had hastily provided, and invited Morton to follow his example, observing, it had been a busy day for them both. Morton declined eating; for the sudden change of circumstances—the transition from the verge of the grave to a prospect of life, had occasioned a dizzy revulsion in his whole system. But the same confused sensation was accompanied by a burning thirst, and he expressed his wish to drink.

“I will pledge you, with all my heart,” said Claverhouse; “for here is a black jack full of ale, and good it must be, if there be good in the country, for the whigs never miss to find it out.—My service to you, Mr Morton,” he said, filling one horn of ale for himself, and handing another to his prisoner.

Morton raised it to his head, and was just about to drink, when the discharge of carabines beneath the window, followed by a deep and hollow groan, repeated twice or thrice, and more faint at each interval, announced the fate of the three men who had just left them. Morton shuddered, and set down the untasted cup.

“You are but young in these matters, Mr Morton,” said Claverhouse, after he had very composedly finished his draught; “and I do not think the worse of you as a young soldier for appearing to feel them acutely. But habit, duty, and necessity, reconcile men to every thing.”

“I trust,” said Morton, “they will never reconcile me to such scenes as these.”

“You would hardly believe,” said Claverhouse in reply, “that, in the beginning of my military career, I had as much aversion to seeing blood spilt as ever man felt; it seemed to me to be wrung from my own heart; and yet, if you trust one of those whig fellows, he will tell you I drink a warm cup of it every morning before I breakfast. [Note: The author is uncertain whether this was ever said of Claverhouse. But it was currently reported of Sir Robert Grierson of Lagg, another of the persecutors, that a cup of wine placed in his hand turned to clotted blood.] But in truth, Mr Morton, why should we care so much for death, light upon us or around us whenever it may? Men die daily—not a bell tolls the hour but it is the death-note of some one or other; and why hesitate to shorten the span of others, or take over-anxious care to prolong our own? It is all a lottery—when the hour of midnight came, you were to die—it has struck, you are alive and safe, and the lot has fallen on those fellows who were to murder you. It is not the expiring pang that is worth thinking of in an event that must happen one day, and may befall us on any given moment—it is the memory which the soldier leaves behind him, like the long train of light that follows the sunken sun—that is all which is worth caring for, which distinguishes the death of the brave or the ignoble. When I think of death, Mr Morton, as a thing worth thinking of, it is in the hope of pressing one day some well-fought and hard-won field of battle, and dying with the shout of victory in my ear—that would be worth dying for, and more, it would be worth having lived for!”

At the moment when Grahame delivered these sentiments, his eye glancing with the martial enthusiasm which formed such a prominent feature in his character, a gory figure, which seemed to rise out of the floor of the apartment, stood upright before him, and presented the wild person and hideous features of the maniac so often mentioned. His face, where it was not covered with blood-streaks, was ghastly pale, for the hand of death was on him. He bent upon Claverhouse eyes, in which the grey light of insanity still twinkled, though just about to flit for ever, and exclaimed, with his usual wildness of ejaculation, “Wilt thou trust in thy bow and in thy spear, in thy steed and in thy banner? And shall not God visit thee for innocent blood?—Wilt thou glory in thy wisdom, and in thy courage, and in thy might? And shall not the Lord judge thee?—Behold the princes, for whom thou hast sold thy soul to the destroyer, shall be removed from their place, and banished to other lands, and their names shall be a desolation, and an astonishment, and a hissing, and a curse. And thou, who hast partaken of the wine-cup of fury, and hast been drunken and mad because thereof, the wish of thy heart shall be granted to thy loss, and the hope of thine own pride shall destroy thee. I summon thee, John Grahame, to appear before the tribunal of God, to answer for this innocent blood, and the seas besides which thou hast shed.”

He drew his right hand across his bleeding face, and held it up to heaven as he uttered these words, which he spoke very loud, and then added more faintly, “How long, O Lord, holy and true, dost thou not judge and avenge the blood of thy saints!”

As he uttered the last word, he fell backwards without an attempt to save himself, and was a dead man ere his head touched the floor.

Morton was much shocked at this extraordinary scene, and the prophecy of the dying man, which tallied so strangely with the wish which Claverhouse had just expressed; and he often thought of it afterwards when that wish seemed to be accomplished. Two of the dragoons who were in the apartment, hardened as they were, and accustomed to such scenes, showed great consternation at the sudden apparition, the event, and the words which preceded it. Claverhouse alone was unmoved. At the first instant of Mucklewrath’s appearance, he had put his hand to his pistol, but on seeing the situation of the wounded wretch, he immediately withdrew it, and listened with great composure to his dying exclamation.

When he dropped, Claverhouse asked, in an unconcerned tone of voice—“How came the fellow here?—Speak, you staring fool!” he added, addressing the nearest dragoon, “unless you would have me think you such a poltroon as to fear a dying man.”

The dragoon crossed himself, and replied with a faltering voice,—“That the dead fellow had escaped their notice when they removed the other bodies, as he chanced to have fallen where a cloak or two had been flung aside, and covered him.”

“Take him away now, then, you gaping idiot, and see that he does not bite you, to put an old proverb to shame.—This is a new incident, Mr. Morton, that dead men should rise and push us from our stools. I must see that my blackguards grind their swords sharper; they used not to do their work so slovenly.—But we have had a busy day; they are tired, and their blades blunted with their bloody work; and I suppose you, Mr Morton, as well as I, are well disposed for a few hours’ repose.”

So saying, he yawned, and taking a candle which a soldier had placed ready, saluted Morton courteously, and walked to the apartment which had been prepared for him.

Morton was also accommodated, for the evening, with a separate room. Being left alone, his first occupation was the returning thanks to Heaven for redeeming him from danger, even through the instrumentality of those who seemed his most dangerous enemies; he also prayed sincerely for the Divine assistance in guiding his course through times which held out so many dangers and so many errors. And having thus poured out his spirit in prayer before the Great Being who gave it, he betook himself to the repose which he so much required.