Полная версия

Полная версияLife of Napoleon Bonaparte. Volume V

7. The nine thousand pounds sterling which we gave to Count and Countess Montholon, should, if they have been paid, be deducted and carried to the account of the legacies which we have given to him by our testament. If they have not been paid, our notes of hand shall be annulled.

8. In consideration of the legacy given by our will to Count Montholon, the pension of twenty thousand francs granted to his wife, is annulled. Count Montholon is charged to pay it to her.

9. The administration of such an inheritance, until its final liquidation, requiring expenses of offices, of journeys, of missions, of consultations, and of law-suits, we expect that our testamentary executors shall retain three per cent upon all the legacies, as well upon the six million eight hundred thousand francs, as upon the sums contained in the codicils, and upon the two millions of the private domain.

10. The amount of the same thus retained, shall be deposited in the hands of a treasurer, and disbursed by drafts from our testamentary executors.

11. If the sums arising from the aforesaid deductions be not sufficient to defray the expenses, provision shall be made to that effect, at the expense of the three testamentary executors and the treasurer, each in proportion to the legacy which we have bequeathed to them in our will and codicils.

12. Should the sums arising from the before-mentioned subtractions be more than necessary, the surplus shall be divided amongst our three testamentary executors and the treasurer, in the proportion of their respective legacies.

13. We nominate Count Las Cases, and in default of him, his son, and in default of the latter, General Drouot, to be treasurer.

This present codicil is entirely written with our hand, signed, and sealed with our arms.

NapoleonThis 24th of April, 1821. Longwood.This is my Codicil or Act of my last WillUpon the funds remitted in gold to the Empress Maria Louise, my very dear and well-beloved spouse, at Orleans, in 1814, she remains in my debt two millions, of which I dispose by the present codicil, for the purpose of recompensing my most faithful servants, whom moreover I recommend to the protection of my dear Marie Louise.

1. I recommend to the empress to cause the income of thirty thousand francs, which Count Bertrand possessed in the duchy of Parma, and upon the Mont Napoleon at Milan, to be restored to him, as well as the arrears due.

2. I make the same recommendation to her with regard to the Duke of Istria, Duroc's daughter, and others of my servants who have continued faithful to me, and who are always dear to me. She knows them.

3. Out of the above-mentioned two millions, I bequeath three hundred thousand francs to Count Bertrand, of which he will lodge one hundred thousand in the treasurer's chest, to be employed in legacies of conscience, according to my dispositions.

4. I bequeath two hundred thousand to Count Montholon, of which he will lodge one hundred thousand in the treasurer's chest, for the same purpose as above-mentioned.

5. Item, Two hundred thousand to Count Las Cases, of which he will lodge one hundred thousand in the treasurer's chest, for the same purpose as above-mentioned.

6. Item, To Marchand, one hundred thousand, of which he will place fifty thousand in the treasurer's chest, for the same purpose as above-mentioned.

7. To Jean Jerome Levie, the mayor of Ajaccio at the commencement of the Revolution, or to his widow, children, or grand-children, one hundred thousand francs.

8. To Duroc's daughter, one hundred thousand.

9. To the son of Bessières, Duke of Istria, one hundred thousand.

10. To General Drouot, one hundred thousand.

11. To Count Lavalette, one hundred thousand.

12. Item, One hundred thousand; that is to say, twenty-five thousand to Piéron, my maître d'hôtel; twenty-five thousand to Novarre, my huntsman; twenty-five thousand to St. Denis, the keeper of my books; twenty-five thousand to Santini, my former door-keeper.

13. Item, One hundred thousand; that is to say, forty thousand to Planta, my orderly officer; twenty thousand to Hebert, lately housekeeper of Rambouillet, and who belonged to my chamber in Egypt; twenty thousand to Lavigné, who was lately keeper of one of my stables, and who was my jockey in Egypt; twenty thousand to Jeanet Dervieux, who was overseer of the stables, and served in Egypt with me.

14. Two hundred thousand francs shall be distributed in alms to the inhabitants of Brienne-le-Chateau, who have suffered most.

15. The three hundred thousand francs remaining, shall be distributed to the officers and soldiers of my guard at the island of Elba, who may be now alive, or to their widows or children, in proportion to their appointments; and according to an estimate which shall be fixed by my testamentary executors. Those who have suffered amputation, or have been severely wounded, shall receive double: The estimate of it to be fixed by Larrey and Emmery.

This codicil is written entirely with my own hand, signed, and sealed with my arms.

Napoleon.[On the back of the codicil is written:]This is my codicil, or act of my last will – the execution of which I recommend to my dearest wife, the Empress Marie Louise.

(L. S.)

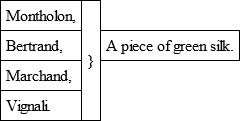

Napoleon.[Attested by the following witnesses, whose seals are respectively affixed:]

Monsieur Lafitte, I remitted to you, in 1815, at the moment of my departure from Paris, a sum of near six millions, for which you have given me a receipt and duplicate. I have cancelled one of the receipts, and I charge Count Montholon to present you with the other receipt, in order that you may pay to him, after my death, the said sum, with interest at the rate of five per cent. from the 1st of July, 1815, deducting the payments which you have been instructed to make by virtue of my orders.

It is my wish that the settlement of your account may be agreed upon between you, Count Montholon, Count Bertrand, and the Sieur Marchand; and this settlement being made, I give you, by these presents, a complete and absolute discharge from the said sum.

I also, at that time, placed in your hands a box, containing my cabinet of medals. I beg you will give it to Count Montholon.

This letter having no other object, I pray God, Monsieur Lafitte, to have you in his holy and good keeping.

Napoleon.Longwood, Island of St. Helena,

the 25th April, 1821.

7th CodicilMonsieur le Baron Labouillerie, treasurer of my private domain, I beg you to deliver the account and the balance, after my death, to Count Montholon, whom I have charged with the execution of my will.

This letter having no other object, I pray God, Monsieur le Baron Labouillerie, to have you in his holy and good keeping.

Napoleon.Longwood, Island of St. Helena,

the 25th April, 1821.

THE END1

See ante, vol. iv., p. 356.

2

Moniteur, March 11.

3

"This was the best fought action during the campaign: the numbers engaged on both sides were nearly equal; the superiority, if any, being on the side of the French." – Lord Burghersh, Operations, &c., p. 196.

4

Baron Fain, p. 193.

5

Moniteur, March 14.

6

Baron Fain, p. 194.

7

"Whatever might have been the hardships of the campaign, and the importance of occasional circumstances, Napoleon superintended and regularly provided for everything; and, up to the present moment, showed himself adequate to direct the affairs of the interior, as well as the complicated movements of the army." – Baron Fain, p. 195.

8

The words alleged to convey such extensive powers as totally to recall and alter every former restriction upon Caulaincourt's exercise of his own opinion, are contained, as above stated, in a letter from Rheims, dated 17th March, 1814. "I have charged the Duke of Bassano to answer your letter in detail. I give you directly the authority to make such concessions as shall be indispensable to maintain the continuance (activité) of the negotiations, and to arrive at a knowledge of the ultimatum of the allies; it being distinctly understood that the treaty shall have for its immediate result the evacuation of our territory, and the restoring prisoners on both sides." – Napoleon, Mémoires, tom. ii., p. 399.

9

Lord Burghersh, in his memoranda previously quoted, states that Lord Castlereagh was not at Troyes upon this occasion, that he made no such declaration as Sir Walter Scott ascribes to him: and that any such declaration would have been uncalled for, as Prince Schwartzenberg was bent on concentrating his forces at Arcis – which he did. Compare "Operations," &c., p. 179. – Ed. (1842.)

10

For Messieurs de Polignac, we should read Monsieur de Vitrolles. – See Lord Burghersh's "Operations," p. 266. Note.– Ed. (1842.)

11

Memoir of the Operations of the Allied Armies in 1813 and 1814. By Lord Burghersh.

12

Jomini, tom. iv., 564.

13

Henry IV., act ii., scene ii.

14

"Mon Amie, j'ai été tous les jours à cheval; le 20 j'ai pris Arcis-sur-Aube. L'ennemi m'y attaqua à 8 heures du soir: le même soir je l'ai battu, et lui ai fait 4000 morts: je lui ai pris 2 pieces de canon et même repris 2: ayant quitté le 21, l'armée ennemie s'est mise, en battaille pour protéger la marche de ses armées, sur Brienne, et sur Bar-sur-Aube, j'ai décidé de me porter sur la Marne et ses environs afin de la pousser plus loin de Paris, en me rapprochant de mes places. Je serai ce soir à St. Dizier. Adieu, mon amie, embrassez mon fils."

15

"General Muffling told me that the word St. Dizier, of so much importance, was so badly written, that they were several hours in making it out. Blucher forwarded the letter to Maria Louisa, with a letter in German, saying, that as she was the daughter of a respectable sovereign, who was fighting in the same cause with himself, he had sent it to her." —Memorable Events, p. 98.

16

Lord Burghersh, Observations, &c., p. 232; Baron Fain, p. 222.

17

"At half past ten on the morning of the 29th, the Empress, in a brown cloth riding-habit, with the King of Rome, in one coach, surrounded by guards, and followed by several other coaches, with attendants, quitted the palace; the spectators observing the most profound silence." —Memorable Events in Paris in 1814, p. 50.

18

Souvenirs de Mad. Durand, tom. i., p. 205.

19

"I saw the proclamation of Roi Joseph selling for a sous, on the Boulevards, where groups of people were assembled. The flight of the Empress caused considerable alarm. Many loudly expressed their discontent at the national guard, for permitting her to leave Paris, as they entertained a dastardly hope that her presence would preserve them from the vengeance of the allies. For the first time I heard the people openly dare to vent complaints against the Emperor, as the sole cause of their impending calamity; but I witnessed no patriotic feeling to repulse the enemy." —Memorable Events, p. 53.

20

Lord Burghersh's account states, that the village of Pantin was attacked, but never retaken by the French. – "Operations," p. 240. – Ed. (1842.)

21

"Prince Joseph, observing the vast number of the enemy's troops that had arrived at the foot of Montmartre, was convinced that the capitulation could be no longer delayed. He gave the necessary powers to the Duke of Ragusa; and immediately proceeded to join the government at Blois." – Baron Fain, p. 232.

22

"During the battle, the Boulevards des Italiens, and the Caffé Tortoni, were thronged with fashionable loungers of both sexes, sitting as usual on the chairs placed there, and appearing almost uninterested spectators of the number of wounded French, and prisoners of the allies which were brought in. About two o'clock, a general cry of sauve qui peut was heard on the Boulevards; this caused a general and confused flight, which spread like the undulations of a wave, even beyond the Pont Neuf. During the whole of the battle, wounded soldiers crawled into the streets, and lay down to die on the pavement. The Moniteur of this day was a full sheet; but no notice was taken of the war or the army. Four columns were occupied by an article on the dramatic works of Denis, and three with a dissertation on the existence of Troy." —Memorable Events, pp. 90-93.

23

The passage is curious, whether we regard it as really emanating from Fouché, or placed in the mouth of that active revolutionist by some one who well understood the genius of the party. "Had I been at Paris at that time," (the period of the siege, namely,) "the weight of my influence, doubtless, and my perfect acquaintance with the secrets of every party, would have enabled me to give these extraordinary events a very different direction. My preponderance, and the promptness of my decision, would have predominated over the more slow and mysterious influence of Talleyrand. That elevated personage could not have made his way unless we had been harnessed to the same car. I would have revealed to him the ramifications of my political plan, and, in spite of the odious policy of Savary, the ridiculous government of Cambacérès, the lieutenancy of the puppet Joseph, and the base spirit of the Senate, we would have breathed new life into the carcase of the Revolution, and these degraded patricians would not have thought of acting exclusively for their own interests. By our united impulse, we would have pronounced before the interference of any foreign influence, the dethronement of Napoleon, and proclaimed the Regency, of which I had already traced the basis. This conclusion was the only one which could have preserved the Revolution and its principles." —Mémoires, tom. ii., p. 229.

24

Las Cases, tom. ii., p. 251.

25

London Gazette, April 5. – "Early in the morning of the 31st March, before the barriers, were open, the soldiers of the allied army climbed up the pallisades of the barrier Rochechouard to look into Paris. They threw this proclamation over the wall, and through the iron gates." —Memorable Events, p. 124.

26

London Gazette Extraordinary, April 9.

27

"This magnificent pageant far surpassed any idea I had formed of military pomp. The cavalry were fifteen abreast, the artillery five, and the infantry thirty. All the men were remarkably clean, healthy, and well clothed. The bands of music were very fine. The people, astonished at the prodigious number of troops, repeatedly exclaimed, 'Oh! how we have been deceived.'" —Memorable Events, p. 106.

28

Sir Robert Wilson, Sketch of the Military and Political Power of Russia, p. 90.

29

Charles X.

30

Baron Fain, p. 227.

31

It is taken from a work which has remarkable traces of authenticity, General Koch's Mémoires, pour servir à l'Histoire de la Campagne de 1814. See also, Memoirs of the Operations of the Allied Armies, already quoted, p. 208. – S.

32

According to Lord Burghersh, (Operations, p. 249,) Caulaincourt saw the Emperor Alexander at his headquarters, before he entered Paris. – Ed. (1842.)

33

De Pradt, Précis Hist. de la Restauration, p. 54.

34

Dated Paris, March 31, three o'clock in the afternoon. "After some discussion, the Emperor of Russia agreed not to treat with Napoleon, and, at the suggestion of Abbé Louis, nor with any of his family. De Pradt told me he retired into a corner of the apartment, with Roux Laborie, to whom he dictated the Emperor's declaration, which was hastily written with a pencil, and shown to Alexander, who approved of it. Michaud, who was in waiting, caused it immediately to be printed, putting, under the name of the Emperor, 'Michaud, Imprimeur du Roi,' and two hours afterwards it was stuck up in Paris. It was read by the people with great eagerness, and I saw many of them copying it." —Memorable Events, p. 128.

35

On the 3d of April, the Moniteur, in which these documents are given, was declared, by the provisional government, the only official journal.

36

"Napoleon reached Fontainbleau at six in the morning of the 31st March. The large rooms of the castle were shut up, and he repaired to his little apartment on the first storey, parallel with the gallery of Francis I. There he shut himself up for the remainder of the day. Maret was the only one of his ministers who was with him. In the course of that evening, and the following morning, arrived the heads of the columns which Napoleon had brought from Champagne, and the advanced guard of the troops from Paris. These wrecks of the army assembled round Fontainbleau. Moncey, who commanded the national guard of Paris, Lafebvre, Ney, Macdonald, Oudinot, Berthier, Mortier, and Marmont, arrived at Napoleon's headquarters; so that he still had an army at his disposal." – Baron Fain, p. 355.

"Marmont arrived at Fontainbleau, at three in the morning of the 1st of April, and gave Napoleon a detailed account of what had passed at Paris. The maréchal told me he appeared undetermined whether to retire on the banks of the Loire, or give battle to the allies near Paris. In the afternoon he went to inspect the position of Marmont's army at Essonne, with which he appeared to be satisfied, and determined to remain there and manœuvre, with a view to disengage Paris and give battle. With the greatest coolness he formed plans for the execution of these objects; but, while thus employed, the officers, whom the maréchal had left at Paris to deliver up that city to the allies, arrived, and informed them of the events of the day. Napoleon, hearing this, became furious: He raved about punishing the rebellious city, and giving it up to pillage. With this resolution he separated from Marmont, and returned to Fontainbleau." —Memorable Events, p. 201.

37

"Soldiers! the enemy has stolen three marches upon us, and has made himself master of Paris. He must be driven out of it. Unworthy Frenchmen, emigrants, whom we had pardoned, have adopted the white cockade, and have joined our enemies. Wretches! they shall receive the reward of this new crime. Let us swear to conquer or to die, and to cause to be respected that tri-coloured cockade, which, during twenty years, has found us in the paths of glory and of honour." – Lord Burghersh, Observations, &c., p. 274.

38

"Ney produced the Moniteur, containing the decree of forfeiture, and advised him to acquiesce and abdicate. Napoleon feigned to read, turned pale, and appeared much agitated; but did not shed tears, as the newspapers reported. He seemed not to know in what manner to act. He then asked, 'Que voulez vous?' Ney answered, 'Il n'y a que l'abdication qui puisse vous tirer de là.' During this conference, Lefebvre came in; and upon Napoleon expressing astonishment at what had been announced to him, said, in his blunt manner, 'You see what has resulted from not listening to the advice of your friends to make peace: you remember the communication I made to you lately, therefore you may think yourself well off that affairs have terminated as they have.'" —Memorable Events, p. 206.

39

Baron Fain, p. 373.

40

"He threw himself on a small yellow sofa, placed near the window, and striking his thigh with a sort of convulsive action, exclaimed, 'No, gentlemen, no! No regency! With my guard and Marmont's corps, I shall be in Paris to-morrow.'" – Bourrienne, tom. i., p. 87. – On the day of the entrance of the allies into Paris, Bourrienne, Napoleon's ex-private secretary, was appointed to the important office of Postmaster-General; a situation from which he was dismissed at the end of three weeks.

41

"Immediately after their departure, Napoleon despatched a courier to the Empress, from whom he had received letters, dated Vendome. He authorised her to despatch to her father, the Duke of Cadore (Champagny,) to solicit his intercession in favour of herself and her son. Overpowered by the events of the day, he shut himself up in his chamber." – Baron Fain, p. 374.

42

"Marmont was not guilty of treachery in defending Paris; but history will say, that had it not been for the defection of the sixth corps, after the allies had entered Paris, they would have been forced to evacuate that great capital; for they would never have given battle on the left bank of the Seine, with Paris in their rear, which they had only occupied for two days; they would never have thus violated every rule and principle of the art of war." – Napoleon, Montholon, tom. ii., p. 265.

43

Lord Burghersh, Observations, p. 296; Savary, tom. iv., p. 76.

44

There are some slight discrepancies between the account of Marmont's proceedings in the text, and that given by Lord Burghersh in his "Memoir on the Operations," pp. 298, 299. – Ed. (1842.)

45

Lord Burghersh's Memorandum says these were Wurtemberg and Austrian troops, commanded by the Prince Royal of Wurtemberg. – Ed. (1842.)

46

Lord Burghersh, Observations, &c., p. 301.

47

Baron Fain, p. 375.

48

"From the way in which this is related, it would be thought that Napoleon despised his native country; but I must suggest a more natural interpretation, and one more conformable to the character of Napoleon, namely, that after his abdication he had no desire to remain in the French territories." – Louis Buonaparte.

49

For the Treaty of Fontainbleau, see Parl. Debates, vol. xxviii., p. 201.

50

See Dispatch from Lord Castlereagh to Earl Bathurst, dated Paris, April 13, 1814, Parl. Papers, 1814.

51

The man had to plead his desire to remain with his wife and family, rather than return to a severe personal thraldom. – S. – "I was by no means astonished at Roustan's conduct he was imbued with the sentiments of a slave, and finding me no longer the master, he imagined that his services might be dispensed with." – Napoleon, Las Cases, tom. i., p. 336.

52

Baron Fain, p. 400.

53

The faithful few were, the Duke of Bassano, the Duke of Vicenza, Generals Bertrand, Flahaut, Belliard, Fouler; Colonels Bassy, Anatole de Montesquiou, Gourgaud, Count de Turenne; Barons Fain, Mesgrigny, De la Place, and Lelorgne d'Ideville; the Chevalier Jouanne, General Kosakowski, and Colonel Vensowitch. The two last were Poles.

54

Count Schouwalow was a Russian, not an Austrian minister. Prince Esterhazy, however, was there. —From Lord Burghersh.– Ed. (1842.)

55

Savary, tom. iv., pp. 118-132.

56

Her two grandsons walked as chief mourners; and in the procession were Prince Nesselrode, General Sacken and Czernicheffe, besides several other generals of the allied army, and some of the French maréchals and generals. The body has since been placed in a magnificent tomb of white marble, erected by her two children, with this inscription —