Полная версия

Полная версияLife of Napoleon Bonaparte. Volume V

That our retreat in case of a reverse, was sufficiently provided for, we trust, notwithstanding the criticism above noticed, to establish in a satisfactory manner. Our position was sufficiently in advance of the entrance of the chaussée into the forest, to give a free approach from every part of the field to that point; which the unenclosed state of the country afforded the troops every means of profiting by. Had our first position been forced, the village of Mont St. Jean, at the junction of the two chaussées, afforded an excellent centre of support for a second, which the enemy would have had equal difficulty in carrying; – besides which there is another farm house and wood immediately behind Mont St. Jean, and in front of the entrance of the forest; which would have enabled us to keep open that entrance. By occupying these points, we might have at any time effected a retreat; and with sufficient leisure to have allowed all the guns, that were in a state to be moved, to file off into the forest. Undoubtedly, had our centre been broken by the last attack of the enemy [about half-past seven,] a considerable part of our artillery must have been left behind, a number of guns disabled, and many men and horses killed and wounded; these must have fallen into the enemy's hands; also the brigades at the points attacked, which were placed rather in front of the infantry, and remained until the last, firing grape-shot into the enemy's columns. The men and horses would have saved themselves with the infantry, and soon found a fresh equipment in the fortresses. The troops at Hougomont would have been cut off had that attack succeeded, but their retreat was open, either upon the corps of 16,000 men left at Halle to cover Brussels, or upon Braine la Leude, which was occupied by a brigade of infantry, who had strengthened their post; between which and our right flank a brigade of cavalry kept a communication open. From Braine la Leude there is a very good road through the forest by Alemberg to Brussels, by which the troops and artillery of our right flank could have effected their retreat. If we now suppose, that the enemy, instead of our right centre, had broken our left centre by the great attack made on it at three o'clock, Ohain afforded nearly the same advantage to the left of our army that Braine la Leude would have done on the right. A road leads from it through the forest to Brussels; or that wing might have retired on the Prussians at Wavre; so that, had either of these two grand attacks succeeded, the retreat into the defiles of the forest need not have been precipitated. It is no fault of our troops to take alarm and lose confidence, because they find themselves turned or partially beaten. Of this many instances might be given. The best proof, however, is, that the enemy can scarcely claim having made a few hundred prisoners during the whole of the last war. No success on the part of the enemy, which they had a right to calculate on, could have then precipitated us into the forest in total disorder. The attacks we sustained to the last on the 18th, were as determined and severe as can be conceived. Still, to the last, a part of the reserve and the cavalry had not suffered much; whereas the French cavalry (heavy) had all been engaged before five o'clock, and were not in a state, from the severe losses they had sustained, to take advantage of a victory.332

But suppose we had been driven into the wood in a state of deroute, similar to what the French were, the forest did not keep us hermetically sealed up, as an impenetrable marsh did the defeated troops at Austerlitz. The remains of our shattered battalions would have gained the forest, and found themselves in security. It consists of tall trees without underwood, passable almost any where for men and horses. The troops could, therefore, have gained the chaussée through it, and when we at last came to confine ourselves to the defence of the entrance to the forest, every person, the least experienced in war, knows the extreme difficulty in forcing infantry from a wood which cannot be turned. A few regiments, with or without artillery, would have kept the whole French army in check, even if they had been as fresh as the day they crossed the frontiers.333 Indeed, the forest in our rear gave us so evident an advantage, that it is difficult to believe that an observation to the contrary was made by Napoleon. Could he quite forget his own retreat? It little availed him to have two fine chaussées, and an open country in his rear; his materiel was all abandoned, and not even a single battalion kept together.

The two farms in front of the position of Mont St. Jean, gave its principal strength. That of Hougomont, with its gardens and enclosures, could contain a force sufficient to make it a most important post. La Haye Sainte was too small for that purpose; otherwise its situation in the Genappe chaussée, in the centre of the position, rendered it better adapted for that purpose. These farms lay on the slope of the valley, about 1500 yards apart, in front of our line; so that no column of the enemy could pass between them, without being exposed to a flank fire. Indeed, without these posts, the ground gave us little advantage over our enemy, except the loss he must be necessarily exposed to in advancing in column upon a line already fixed.

From these observations it will appear that our retreat was well secured, and that the advantages of the position for a field of battle were very considerable; so that there was little risk but that it would have been successfully defended, even if the Prussians had by "some fatality" been prevented from forming a junction. The difficulties of the roads, from the severe rains, detained them from joining us at least double the time that was calculated upon. We had therefore to sustain the attack of a superior army so much longer; yet they were not able to make any impression. Every attack had been most successfully repulsed; and we may safely infer that, even if the Prussians had not joined in time, we would still have been able to maintain our position, and repulse the enemy, but might have been perhaps unable, as was the case at Talavera, to profit by this advantage, or to follow up our success.334

The morning of the 18th, and part of the forenoon, were passed by the enemy in a state of supineness, for which it was difficult to account. The rain had certainly retarded his movements, more particularly that of bringing his artillery into position; yet it was observed that this had been accomplished at an early hour. In Grouchy's publication, we find a reason which may have caused this delay; namely, that Napoleon's ammunition had been so much exhausted in the preceding actions, that there was only a sufficiency with the army for an action of eight hours. Buonaparte states [Liv. ix.] that it was necessary to wait until the ground was sufficiently dried, to enable the cavalry and artillery to manœuvre [Montholon, tom. ii., p. 136;] however, in such a soil, a few hours could make very little difference, particularly as a drizzling rain continued all the morning, and indeed after the action had commenced. The heavy fall of rain on the night of the 17th to 18th, was no doubt more disadvantageous to the enemy than to the troops under Lord Wellington; the latter were in position, and had few movements to make; whilst the enemy's columns, and particularly his cavalry, were much fatigued and impeded by the state of the ground, which, with the trampled corn, caused them to advance more slowly, and kept them longer under fire. On the other hand, the same causes delayed the Prussians in their junction, which they had promised to effect at eleven o'clock, and obliged Lord Wellington to maintain the position alone, nearly eight hours longer than had been calculated upon.

About twelve o'clock, the enemy commenced the action by an attack upon Hougomont, with several columns, preceded by numerous light troops, who, after severe skirmishing, drove the Nassau troops from the wood in its front, and established themselves in it. This attack was supported by the constant fire of a numerous artillery. A battalion of the Guards occupied the house and gardens, with the other enclosures, which afforded great facilities for defence; and after a severe contest, and immense loss, the enemy were repulsed, and a great part of the wood regained.335

During the early part of the day, the action was almost entirely confined to this part of the line, except a galling fire of artillery along the centre, which was vigorously returned by our guns. This fire gradually extended towards the left, and some demonstrations of an attack of cavalry were made by the enemy. As the troops were drawn up on the slope of the hill, they suffered most severely from the enemy's artillery. In order to remedy this, Lord Wellington moved them back about 150 or 200 yards, to the reverse slope of the hill, to shelter them from the direct fire of the guns; our artillery in consequence remained in advance, that they might see into the valley. This movement was made between one and two o'clock by the duke in person; it was general along the front or centre of the position, on the height to the right of La Haye Sainte.

It is by no means improbable, that the enemy considered this movement as the commencement of a retreat, since a considerable portion of our troops were withdrawn from his sight, and determined in consequence to attack our left centre, in order to get possession of the buildings, called Ferme de M. St. Jean, or of the village itself, which commanded the point of junction of the two chaussées. The attacking columns advanced on the Genappe chaussée, and by the side of it; they consisted of four columns of infantry (D'Erlon's corps, which was not engaged on the 16th,) thirty pieces of artillery, and a large body of cuirassiers (Milhaud's.) On the left of this attack, the French cavalry took the lead of the infantry, and had advanced considerably, when the Duke of Wellington ordered the heavy cavalry (Life Guards) to charge them as they ascended the position near La Haye Sainte. They were driven back on their own position, where the chaussée, being cut into the rising ground, leaves steep banks on either side. In this confined space they fought at swords' length for some minutes, until the enemy brought down some light artillery from the heights, when the British cavalry retired to their own position. The loss of the cuirassiers did not appear great. They seemed immediately to reform their ranks, and soon after advanced to attack our infantry, who were formed into squares to receive them, being then unsupported by cavalry. The columns of infantry in the mean time, pushed forward on our left of the Genappe chaussée, beyond La Haye Sainte, which they did not attempt in this attack to take. A Belgian brigade of infantry, formed in front, gave way, and these columns crowned the position. When Sir Thomas Picton moved up the brigade of General Pack from the second line (the 92d regiment in front,) which opened a fire on the column just as it gained the height, and advanced upon it. When within thirty yards, the column began to hesitate; at this moment a brigade of heavy cavalry (the 1st and 2d dragoons) wheeled round the 92d regiment, and took the column in flank; a total rout ensued; the French, throwing down their arms, ran into our position to save themselves from being cut down by the cavalry; many were killed, and two eagles, with 2000 prisoners, taken. But the cavalry pursued their success too far, and being fired upon by one of the other columns, and at the same time, when in confusion, being attacked by some French cavalry who had been sent to support the attack, the British were obliged to retire with considerable loss. In this attack the enemy had brought forward several pieces of artillery, which were captured by our cavalry; the horses in the guns were killed, and we were obliged to abandon the guns. General Ponsonby, who commanded the cavalry, was killed. The gallant Sir Thomas Picton also fell, leading on his division to repel this attack.336 The number of occurrences which crowded on the attention, rendered it impossible for any individual to see the whole action, and in the midst of noise, bustle, and personal danger, it is difficult to note the exact time in which the event happens.337

It is only afterwards, in discussing the chances and merits of each, that such questions become of interest, which may in some measure account for the discrepancy of the statements of officers present, as to the time and circumstances of some of the principal events. From this period, half-past two, until the end of the action, the British cavalry were scarcely engaged, but remained in readiness in the second line.338 After the French cuirassiers had re-formed, and were strongly reinforced,339 they again advanced upon our position, and made several desperate attacks upon our infantry, who immediately formed into squares, and maintained themselves with the most determined courage and coolness. Some time previous to this, about three o'clock, an attack was made upon La Haye Sainte, which is merely a small farm-house; it was occupied by two companies of the German Legion. The enemy had advanced beyond it, so that the communication was cut off for some time, and it could not be reinforced. The troops having expended their ammunition, the post was carried. A continued fire was kept up at this point, and the enemy was soon afterwards obliged to abandon it, without being able to avail himself of it as a point of support for his attacking columns. The house was too small for a sufficient number of troops to maintain themselves so close to our position, under such a heavy fire.

The French cavalry, in the attack on the centre of our line above mentioned, were not supported by infantry. They came on, however, with the greatest courage, close to the squares of our infantry; the artillery, which was somewhat in advance, kept up a well-directed fire upon them as they advanced, but on their nearer approach, the gunners were obliged to retire into the squares, so that the guns were actually in possession of the enemy's cavalry, who could not, however, keep possession of them, or even spike them, if they had the means, in consequence of the heavy fire of musketry to which they were exposed. The French accounts say, that several squares were broken, and standards taken, which is decidedly false; on the contrary, the small squares constantly repulsed the cavalry, whom they generally allowed to advance close to their bayonets before they fired. They were driven back with loss on all points, and the artillerymen immediately resumed their guns in the most prompt manner, and opened a severe and destructive fire of grape-shot on them as they retired.340

After the failure of the first attack, the French had little or no chance of success by renewing it; but the officers, perhaps ashamed of the failure of such boasted troops, endeavoured repeatedly to bring them back to charge the squares; but they could only be brought to pass between them, and round them. They even penetrated to our second line, where they cut down some stragglers and artillery-drivers, who were with the limbers and ammunition-waggons. They charged the Belgian squares in the second line, with no better success, and upon some heavy Dutch cavalry showing themselves, they soon retired.

If the enemy supposed us in retreat, then such an attack of cavalry might have led to the most important results; but by remaining so uselessly in our position, and passing and repassing our squares of infantry, they suffered severely by their fire; so much so, that before the end of the action, when they might have been of great use, either in the attack, or in covering the retreat, they were nearly destroyed.341 The only advantage which appeared to result from their remaining in our position, was preventing the fire of our guns on the columns which afterwards formed near La Belle Alliance, in order to debouche for a new attack. The galling fire of the infantry, however, forcing the French cavalry at length to retire into the hollow ground, to cover themselves, the artillerymen were again at their guns, and, being in advance of the squares, saw completely into the valley, and by their well-directed fire, seemed to make gaps in them as they re-formed to repeat this useless expenditure of lives. Had Buonaparte been nearer the front, he surely would have prevented this useless sacrifice of his best troops. Indeed, the attack of cavalry at this period, is only to be accounted for by supposing the British army to be in retreat. He had had no time to avail himself of his powerful artillery to make an impression on that part of the line he meant to attack, as had always been his custom, otherwise it was not availing himself of the superiority he possessed; and it was treating his enemy with a contempt, which, from what he had experienced at Quatre-Bras, could not be justified.342 He allows, in Liv. ix., p. 156, that this charge was made too soon,343 but that it was necessary to support it, and that the cuirassiers of Kellerman, 3000 in number, were consequently ordered forward to maintain the position. And at p. 196 and 157, Liv. ix., he allows that the grenadiers-à-cheval, and dragoons of the guard, which were in reserve, advanced without orders; that he sent to recall them, but, as they were already engaged, any retrograde movement would then have been dangerous. Thus, every attack of the enemy had been repulsed, and a severe loss inflicted. The influence this must have had on the "morale" of each army, was much in favour of the British, and the probability of success on the part of the enemy was consequently diminished from that period.

The enemy now seemed to concentrate their artillery, particularly on the left of the Genappe chaussée, in front of La Belle Alliance, and commenced a heavy fire (a large proportion of his guns were twelve-pounders) on that part of our line extending from behind La Haye Sainte towards Hougomont. Our infantry sheltered themselves by lying down behind the ridge of the rising ground, and bore it with the most heroic patience. Several of our guns had been disabled, and many artillerymen killed and wounded, so that this fire was scarcely returned; but when the new point of attack was no longer doubtful, two brigades were brought from Lord Hill's corps on the right, and were of most essential service.

It may here be proper to consider the situation of the Prussian army, and the assistance they had rendered up to this time, about six o'clock.

The British army had sustained several severe attacks, which had been all repulsed, and no advantage of any consequence had been gained by the enemy. They had possessed part of the wood and garden of Hougomont, and La Haye Sainte, which latter they were unable to occupy. Not a square had been broken, shaken, or obliged to retire. Our infantry continued to display the same obstinacy, the same cool, calculating confidence in themselves, in their commander, and in their officers, which had covered them with glory in the long and arduous war in the Peninsula. From the limited extent of the field of battle, and the tremendous fire their columns were exposed to, the loss of the enemy could not have been less than 15,000 killed and wounded. Two eagles, and 2000 prisoners, had been taken, and their cavalry nearly destroyed. We still occupied nearly the same position as we did in the morning, but our loss had been severe, perhaps not less than 10,000 killed and wounded. Our ranks were further thinned by the numbers of men who carried off the wounded, part of whom never returned to the field. The number of Belgian and Hanoverian troops, many of whom were young levies, that crowded to the rear, was very considerable, besides the number of our own dismounted dragoons, together with a proportion of our infantry, some of whom, as will always be found in the best armies, were glad to escape from the field. These thronged the road leading to Brussels, in a manner that none but an eyewitness could have believed, so that perhaps the actual force under the Duke of Wellington at this time, half-past six, did not amount to more than 34,000 men.344 We had at an early hour been in communication with some patroles of Prussian cavalry on our extreme left. A Prussian corps, under Bulow, had marched from Wavre at an early hour to manœuvre on the right and rear of the French army, but a large proportion of the Prussian army were still on the heights above Wavre, after the action had commenced at Waterloo.345 The state of the roads, and the immense train of artillery they carried, detained Bulow's corps for a remarkably long time; they had not more than twelve or fourteen miles to march. At one o'clock,346 the advanced guard of this corps was discovered by the French; about two o'clock the patroles of Bulow's corps were discovered from part of our position. The French detached some light cavalry to observe them, which was the only diversion that had taken place up to this time. At half-past four, Blucher had joined in person Bulow's corps, at which time two brigades of infantry and some cavalry were detached to act on the right of the French. [Muffling, p. 30.] He was so far from the right of the French, that his fire of artillery was too distant to produce any effect, and was chiefly intended to give us notice of his arrival. [Muffling, p. 31.] It was certainly past five o'clock before the fire of the Prussian artillery (Bulow's corps) was observed from our position, and it soon seemed to cease altogether. It appears that they had advanced, and obtained some success, but were afterwards driven back to a considerable distance by the French, who sent a corps under General Lobau to keep them in check.347 About half-past six, the first Prussian corps came into communication with our extreme left near Ohain.

The effective state of the several armies may be considered to be as follows:

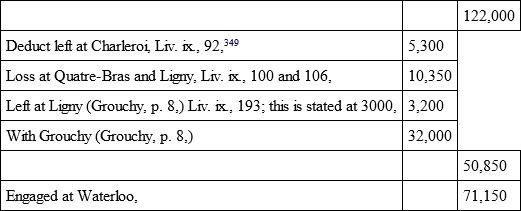

The army under the Duke of Wellington amounted, at the commencement of the campaign, to 75,000 men, including every description of force,348 of which nearly 40,000 were English, or the King's German Legion. Our loss at Quatre-Bras amounted to 4500 killed and wounded, which reduced the army to 70,500 men; of these about 54,000 were actually engaged at Waterloo; about 32,000 were composed of British troops, or the King's German Legion, including cavalry, infantry, and artillery; the remainder, under Prince Frederick, took no part in the action, but covered the approach to Brussels from Nievelles, and were stationed in the neighbourhood of Halle. The French force has been variously stated, and it is not easy to form a very accurate statement of their strength. Batty gives it at 127,000; that is the number which crossed the frontiers. Liv. ix., p. 69, it is given at 122,000. Gourgaud reduces it to 115,000; of these, 21,000 were cavalry, and they had 350 guns. Let us, however, take the statement in Liv. ix., and say,

Примечание 1349

This number, however, is certainly underrated; and there is little doubt but Buonaparte had upwards of 75,000 men under his immediate command on the 18th June.350

Buonaparte, liv. ix., 162, 117, states the Prussian force concentrated at Wavre to be 75,000 men. Grouchy, p. 9, makes it 95,000. It is, however, generally understood that they had not above 70,000 with the army at Wavre.

It may be necessary here to refer to the operations of the corps under Grouchy, who were detached in pursuit of the Prussians. It appears, that at twelve o'clock on the 17th, Buonaparte was ignorant of the direction the Prussian army had taken. – [Grouchy, p. 13.] – It was generally supposed that it was towards Namur. At that hour, Buonaparte ordered Grouchy, with 32,000 men, to follow them. As the troops were much scattered, it was three o'clock before they were in movement, and they did not arrive at Gembloux before the night of the 17th, when Grouchy informed Buonaparte of the direction the Prussian army had taken. He discovered the rear-guard of the Prussians near Wavre about twelve o'clock on the 18th, and at two o'clock he attacked Wavre, which was obstinately defended by General Thielman, and succeeded in obtaining possession of a part of the village. By the gallant defence of this post by General Thielman, Grouchy was induced to believe that the whole Prussian army was before him. Blucher, however, had detached Bulow's corps (4th) at an early hour upon Chapelle-Lambert, to act on the rear of the French army. The movement of this corps was, however, much delayed by a fire which happened at Wavre, and by the bad state of the roads; so that they had great difficulty in bringing up the numerous artillery they carried with this corps, which prevented them from attacking the enemy before half-past four o'clock.351