Полная версия

Полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 20, No. 578, December 1, 1832

See the Engraving, vol. xviii. p. 337 of The Mirror.

POVERTY OF KINGS, AND THE BRITISH CROWN PAWNED

As to increasing wealth by war, that has never yet happened to this nation; and, I believe, rarely to any country. Our former kings most engaged in war were always poor, and sometimes excessively so. Edward III. pawned his jewels to pay foreign forces; and magnam coronam Angliae, his imperial crown, three several times—once abroad, and twice to Sir John Wosenham, his banker, in whose custody the crown remained no less than eight years. The Black Prince, as Walsingham informs us, was constrained to pledge his plate. Henry V., with all his conquests, pawned his crown, and the table and stools of silver which he had from Spain. Queen Elizabeth is known to have sold her very jewels.

G.K.HEAD-DRESS OF THE FOURTEENTH CENTURY, IN ENGLAND

In Wickliffe's Commentaries upon the Ten Commandments, in the midst of a moral exhortation, he manages, by a few bold touches, to give us a picture of the fashionable head-dress of his day:—

"And let each woman beware, that neither by countenance, nor by array of body nor of head, she stir any to covet her to sin. Not crooking (curling) her hair, neither laying it up on high, nor the head arrayed about with gold and precious stones; not seeking curious clothing, nor of nice shape, showing herself to be seemly to fools. For all such arrays of women St. Peter and St. Paul, by the Holy Ghost's teaching, openly forbid."

D.P.SALADS

Oil for salads is mentioned in the Paston Letters, in 1466, in which year Sir John Paston writes to his mother, that he has sent her "ii. potts off oyl for salady's, whyche oyl was goode a myght be when he delyv'yd yt, and schuld be goode at the reseyving yff itt was not mishandled nor miscarryd." This indicates that vegetables for the table were then cultivated in England, although the common opinion is, that most of our fruit and garden productions were destroyed during the civil wars between the houses of York and Lancaster. A good salad, however, had become so scarce some years afterwards, that Katharine, the queen of Henry VIII., is said, on a particular occasion, to have sent to the continent to procure one.

D.P.ADVERTISEMENT OF THE OPENING OF THE LONDON COFFEE HOUSE, UPWARDS OF A CENTURY AGO

"May, 1731.

"Whereas it is customary for Coffee Houses and other Public Houses to take 8s. for a quart of Arrack, and 6s. for a quart of Brandy or Rum, made into Punch;

This is to give Notice,That James Ashley has opened, on Ludgate Hill, the London Coffee House, Punch House, Dorchester Beer and Welsh Ale Warehouse, where the finest and best old Arrack, Rum, and French Brandy is made into Punch, with the other of the finest ingredients—viz.:

"A quart of Arrack made into Punch for six shillings; and so in proportion to the smallest quantity, which is half-a-quartern for fourpence halfpenny.

"A quart of Rum or Brandy made into Punch for four shillings; and so in proportion to the smallest quantity, which is half-a-quartern for threepence; and Gentlemen may have it as soon made as a gill of wine can be drawn."

G.K.SIR WILLIAM JONES'S PLAN OF STUDY

Some idea of the acquirements of the resolute industry with which Jones pursued his studies may be formed from the following memorandum:—

"Resolved to learn no more rudiments of any kind, but to perfect myself in—first, twelve languages, as the means of acquiring accurate knowledge of

I. History1. Man 2. NatureII. Arts1. Rhetoric. 2. Poetry. 3. Painting. 4. MusicIII. Sciences1. Law. 2. Mathematics. 3. Dialectics"N.B. Every species of human knowledge may be reduced to one or other of these divisions. Even law belongs partly to the history of man, partly as a science to dialectics. The twelve languages are Greek, Latin, Italian, French, Spanish, Portuguese, Hebrew, Arabic, Persian, Turkish, German, English.—1780."

SPIRIT OF DISCOVERY

SAILING UP THE ESSEQUIBO

By Captain J.E. Alexander, H.P., late 16th Lancers, M.R.G.S., &cMy purpose was now to proceed up the noble Essequibo river towards the El Dorado of Sir Walter Raleigh, and view the mighty forests of the interior, and the varied and beautiful tribes by which they are inhabited. Our residence on the island of Wakenaam had been truly a tropical one. During the night, the tree frogs, crickets, razor-grinders, reptiles, and insects of every kind, kept up a continued concert. At sunrise, when the flowers unfolded themselves, the humming birds, with the metallic lustre glittering on their wings, passed rapidly from blossom to blossom. The bright yellow and black mocking-birds flew from their pendant nests, accompanied by their neighbours, the wild bees, which construct their earthen hives on the same tree. The continued rains had driven the snakes from their holes, and on the path were seen the bush-master (cona-couchi) unrivalled for its brilliant colours, and the deadly nature of its poison; and the labari equally poisonous, which erects its scales in a frightful manner when irritated. The rattlesnake was also to be met with, and harmless tree snakes of many species. Under the river's bank lay enormous caymen or alligators,—one lately killed measured twenty-two feet. Wild deer and the peccari hog were seen in the glades in the centre of the island; and the jaguar and cougour (the American leopard and lion) occasionally swam over from the main land.

We sailed up the Essequibo for a hundred miles in a small schooner of thirty tons, and occasionally took to canoes or coorials to visit the creeks. We then went up a part of the Mazaroony river, and saw also the unexplored Coioony: these three rivers join their waters about one hundred miles from the mouth of the Essequibo. In sailing or paddling up the stream, the breadth is so great, and the wooded islands so numerous, that it appears as if we navigated a large lake. The Dutch in former times had cotton, indigo, and cocoa estates up the Essequibo, beyond their capital Kykoveral, on an island at the forks or junction of the three rivers. Now, beyond the islands at the mouth of the Essequibo there are no estates, and the mighty forest has obliterated all traces of former cultivation. Solitude and silence are on either hand, not a vestige of the dwellings of the Hollanders being to be seen; and only occasionally in struggling through the entangled brushwood one stumbles over a marble tombstone brought from the shores of the Zuyderzee.

At every turn of the river we discovered objects of great interest. The dense and nearly impenetrable forest itself occupied our chief attention; magnificent trees, altogether new to us, were anchored to the ground by bush-rope, convolvuli, and parasitical plants of every variety. The flowers of these cause the woods to appear as if hung with garlands. Pre-eminent above the others was the towering and majestic Mora, its trunk spread out into buttresses; on its top would be seen the king of the vultures expanding his immense wings to dry after the dews of night. The very peculiar and romantic cry of the bell-bird, or campanero, would be heard at intervals; it is white, about the size of a pigeon, with a leathery excrescence on its forehead, and the sound which it produces in the lone woods is like that of a convent-bell tolling.

A crash of the reeds and brushwood on the river's bank would be followed by a tapir, the western elephant, coming down to drink and to roll himself in the mud; and the manati or river-cow would lift its black head and small piercing eye above the water to graze on the leaves of the coridore tree. They are shot from a stage fixed in the water, with branches of their favourite food hanging from it; one of twenty-two cwt. was killed not long ago. High up the river, where the alluvium of the estuary is changed for white sandstone, with occasionally black oxide of manganese, the fish are of delicious flavour; among others, the pacoo, near the Falls or Rapids, which is flat, twenty inches long, and weighs four pounds; it feeds on the seed of the arum arborescens, in devouring which the Indians shoot it with their arrows: of similar genus are the cartuback, waboory, and amah.

The most remarkable fish of these rivers are, the peri or omah, two feet long; its teeth and jaws are so strong, that it cracks the shells of most nuts to feed on their kernels, and is most voracious; the Indians say that it snaps off the breasts of women, and emasculates men. Also the genus silurus, the young of which swim in a shoal of one hundred and fifty over the head of the mother, who, on the approach of danger, opens her mouth, and thus saves her progeny; with the loricaria calicthys, or assa, which constructs a nest on the surface of pools from the blades of grass floating about, and in this deposits its spawn which is hatched by the sun. In the dry season this remarkable fish has been dug out of the ground, for it burrows in the rains owing to the strength and power of the spine; in the gill-fin and body it is covered with strong plates, and far below the surface finds moisture to keep it alive. The electric eel is also an inhabitant of these waters, and has sometimes nearly proved fatal to the strongest swimmer. If sent to England in tubs, the wood and iron act as conductors, and keep the fish in a continued state of exhaustion, causing, eventually, death: an earthenware jar is the vessel in which to keep it in health.

(To be concluded in our next.)FINE ARTS

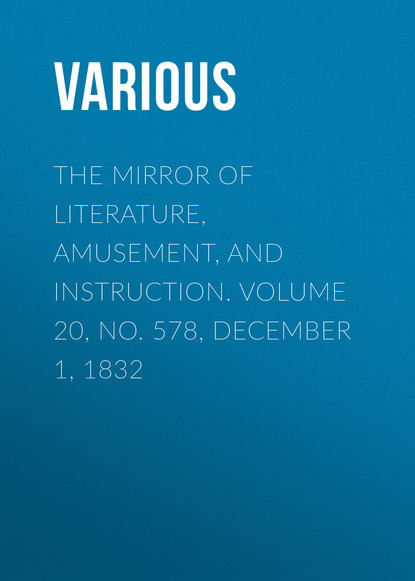

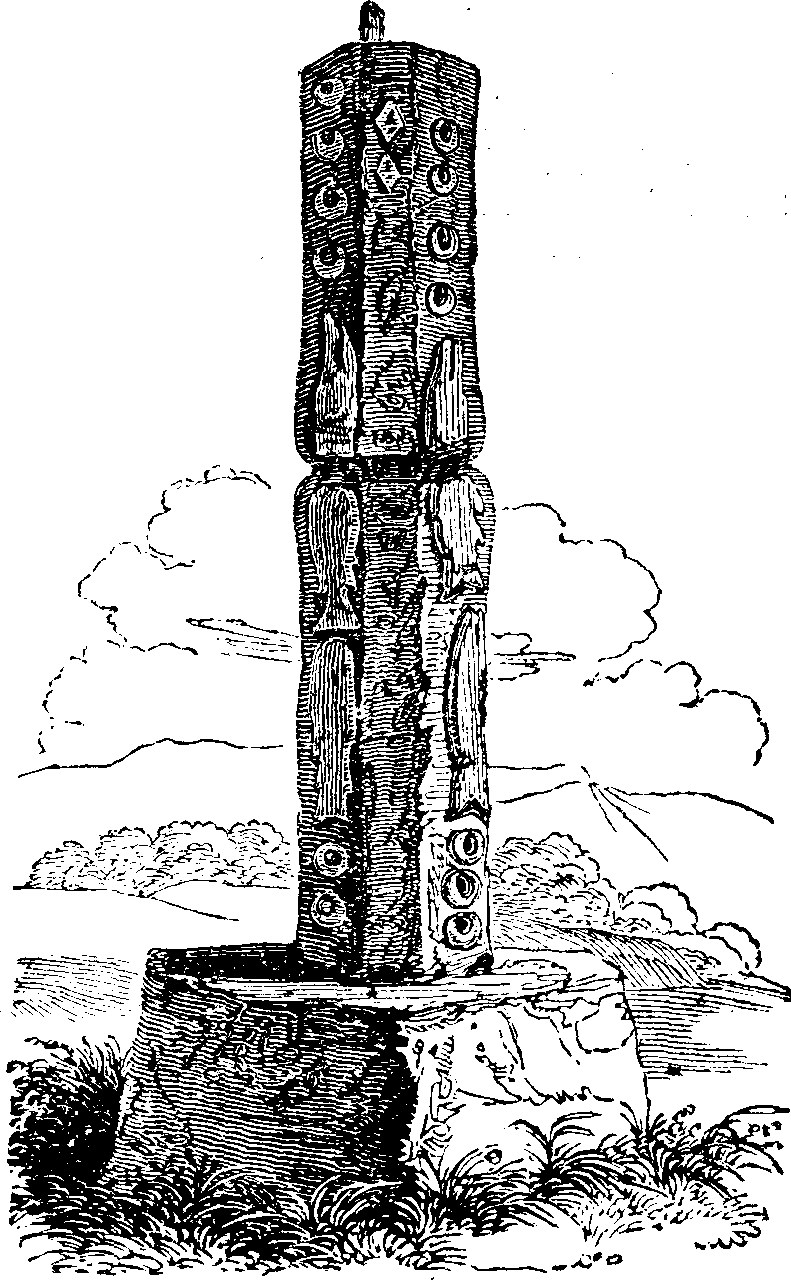

CROSSES. 6

Neville's Cross

We resume the illustration of these curious structures with two specimens of interesting architectural character, and memorable association with our early history. The first is Neville's Cross, at Beaurepaire (or Bear Park, as it is now called), about two miles north-west from Durham. Here David II., King of Scots, encamped with his army before the celebrated battle of Red Hills, or Neville's Cross, as it was afterwards termed, from the above elegant stone cross, erected to record the victory by Lord Ralph Neville. The English sovereign, Edward III., had just achieved the glorious conquest of Crecy; and the Scottish king judged this a fit opportunity for his invasion. However, "the great northern barons of England, Percy and Neville, Musgrave, Scope, and Hastings, assembled their forces in numbers sufficient to show that, though the conqueror of Crecy, with his victorious army, was absent in France, there were Englishmen enough left at home to protect the frontiers of his kingdom from violation. The Archbishops of Canterbury and York, the prelates of Durham, Carlisle, and Lincoln, sent their retainers, and attended the rendezvous in person, to add religious enthusiasm to the patriotic zeal of the barons. Ten thousand soldiers, who had been sent over to Calais to reinforce Edward III.'s army, were countermanded in this exigency, and added to the northern army.7"

The battle, which was fought October 17, 1346, lasted only three hours, but was uncommonly destructive. The English archers, who were in front, were at first thrown into confusion, and driven back; but being reinforced by a body of horse, repulsed their opponents, and the engagement soon became general. The Scottish army was entirely defeated, and the king himself made prisoner; though previous to the fight he is said to have regarded the English with contempt, and as a raw and undisciplined host, by no means competent to resist the power of his more hardy veterans.

"Amid repeated charges, and the most dispiriting slaughter by the continuous discharge of the English arrows, David showed that he had the courage, though not the talents, of his father (Robert Bruce). He was twice severely wounded with arrows, but continued to encourage to the last the few of his peers and officers who were still fighting around him."8 He scorned to ask quarter, and was taken alive with difficulty. Rymer says, "The Scotch king, though he had two spears hanging in his body, his leg desperately wounded, and being disarmed, his sword having been beaten out of his hand, disdained captivity, and provoked the English by opprobrious language to kill him. When John Copeland, who was governor of Roxborough Castle, advised him to yield, he struck him on the face with his gauntlet so fiercely, that he knocked out two of his teeth. Copeland conveyed him out of the field as his prisoner. Upon Copeland's refusing to deliver up his royal captive to the queen (Philippa), who stayed at Newcastle during the battle, the king sent for him to Calais, where he excused his refusal so handsomely, that the king sent him back with a reward of 500l. a year in lands, where he himself should choose it, near his own dwelling, and made him a knight banneret."9

Hume states Philippa to have assembled a body of little more than 12,000 men, and to have rode through the ranks of her army, exhorting every man to do his duty, and to take revenge on these barbarous ravagers. "Nor could she be persuaded to leave the field till the armies were on the point of engaging. The Scots have often been unfortunate in the great pitched battles which they have fought with the English: even though they commonly declined such engagements where the superiority of numbers was not on their side; but never did they receive a more fatal blow than the present. They were broken and chased off the field: fifteen thousand of them, some historians say twenty thousand, were slain; among whom were Edward Keith, Earl Mareschal, and Sir Thomas Charteris, Chancellor: and the king himself was taken prisoner, with the Earls of Sutherland, Fife, Monteith, Carrick, Lord Douglas, and many other noblemen." The captive king was conveyed to London, and afterwards in solemn procession to the Tower, attended by a guard of 20,000 men, and all the city companies in complete pageantry; while "Philippa crossed the sea at Dover, and was received in the English camp before Calais, with all the triumph due to her rank, her merit, and her success." These indeed were bright days of chivalry and gallantry.

"The ground whereon the battle was fought," say the topographers of the county,10 "is about one mile west from Durham; it is hilly, and in some parts very steep, particularly towards the river. Near it, in a deep vale, is a small mount, or hillock, called the Maiden's Bower, on which the holy Corporex Cloth, wherewith St. Cuthbert covered the chalice when he used to say mass, was displayed on the point of a spear, by the monks of Durham, who, when the victory was obtained, gave notice by signal to their brethren stationed on the great tower of the Cathedral, who immediately proclaimed it to the inhabitants of the city, by singing Te Deum. From that period the victory was annually commemorated in a similar manner by the choristers, till the occurrence of the Civil Wars, when the custom was discontinued; but again revived on the Restoration," and observed till nearly the close of the last century.

The site of the Cross is by the road-side: it was defaced and broken down in the year 1589. Its pristine beauty is thus minutely described in Davis's Rights and Monuments: "On the west side of the city of Durham, where two roads pass each other, a most famous and elegant cross of stone work was erected to the honour of God, &c. at the sole cost of Ralph, Lord Neville, which cross had seven steps about it, every way squared to the socket wherein the stalk of the cross stood, which socket was fastened to a large square stone; the sole, or bottom stone being of a great thickness, viz. a yard and a half every way: this stone was the eighth step. The stalk of the cross was in length three yards and a half up to the boss, having eight sides all of one piece; from the socket it was fixed into the boss above, into which boss the stalk was deeply soldered with lead. In the midst of the stalk, in every second square, was the Neville's cross; a saltire in a scutcheon, being Lord Neville's arms, finely cut; and, at every corner of the socket, was a picture of one of the four Evangelists, finely set forth and carved. The boss at the top of the stalk was an octangular stone, finely cut and bordered, and most curiously wrought; and in every square of the nether side thereof was Neville's Cross, in one square, and the bull's head in the next, so in the same reciprocal order about the boss. On the top of the boss was a stalk of stone, (being a cross a little higher than the rest,) whereon was cut, on both sides of the stalk, the picture of our Saviour Christ, crucified; the picture of the Blessed Virgin on one side, and St. John the Evangelist on the other; both standing on the top of the boss. All which pictures were most artificially wrought together, and finely carved out of one entire stone; some parts thereof, though carved work, both on the east and west sides, with a cover of stone likewise over their heads, being all most finely and curiously wrought together out of the same hollow stone, which cover had a covering of lead."

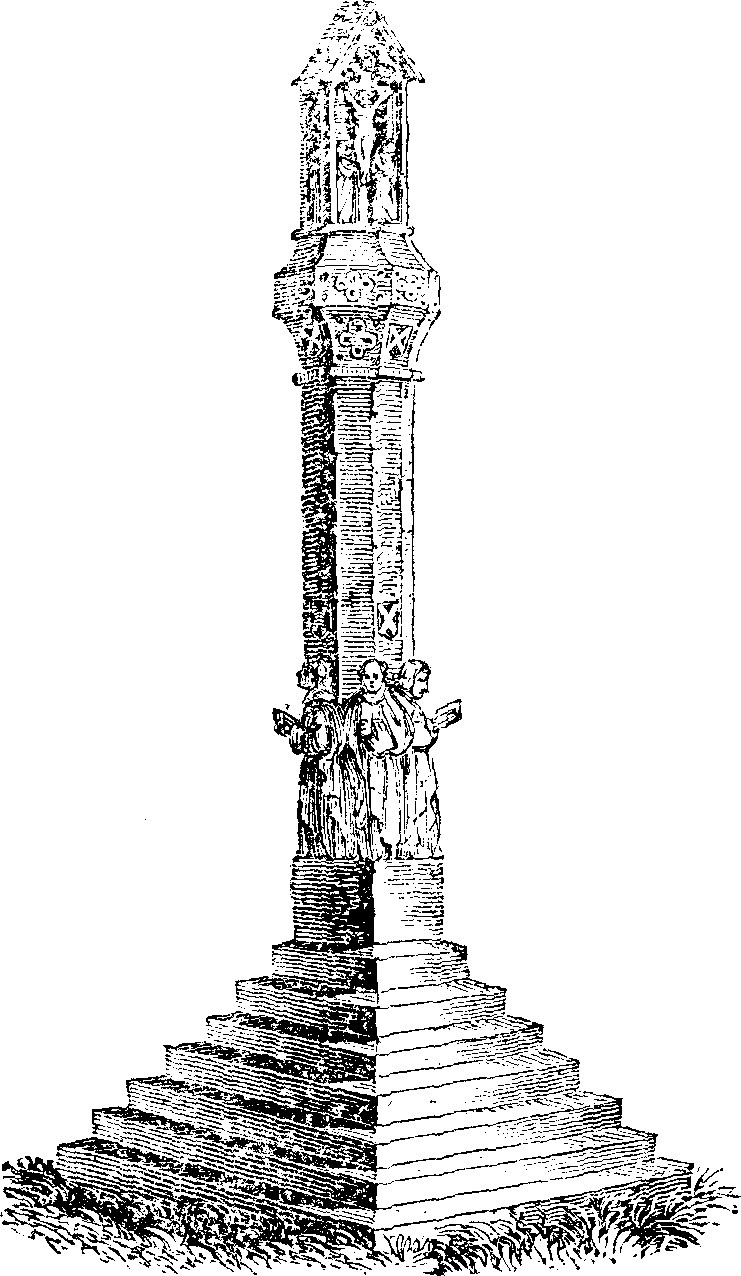

(Percy's Cross.)

The second specimen (see the Cut) stands by the side of the highway over Hedgeley Moor, in the adjoining county of Northumberland. This Cross is a record of the War of the Roses. Here, in one of the skirmishes preliminary to the celebrated victory at Hexham (May 12, 1464), Sir Ralph Percy was slain, by Lord Montacute, or Montague, brother to the Earl of Warwick, and warden of the east marches between Scotland and England. His dying words are stated to have been, "I have saved the bird in my breast:" meaning his faith to his party. The memorial is a square stone pillar, embossed with the arms of Percy and Lucy: they are nearly effaced by time, though the personal valour of the hero is written in the less perishable page of history.

The Nevilles are distinguished personages in the pages of the historians of the North. In Durham they have left a lasting memorial of their magnificence in Raby Castle, the principal founder of which was John de Neville, Earl of Westmoreland; who, in 1379, obtained a license to castellate his manor of Raby; though a part of the structure appears to have been of more ancient date. Leland speaks of it in his time as "the largest castle of lodgings in all the north country." It remains to this day the most perfect castellated mansion, or, more strictly, castle, in the kingdom, and its "hall" eclipses even the chivalrous splendour of Windsor: here 700 knights, who held of the Nevilles, are said to have been entertained at one time. The whole establishment is maintained with much of the hospitable glories of the olden time by the present distinguished possessor of Raby, the Marquess of Cleveland.

WINTER EXHIBITION OF PICTURES, AT THE SUFFOLK-STREET GALLERY

(Concluded from page 231.)144. Landscape and Figures. The first by Gainsborough; the latter by Morland.

145. The Body of Harold discovered by Swanachal and two Monks, the morning after the Battle of Hastings. A.J. Woolmer. A picture of some, and not undeserved, distinction in a previous exhibition.

150. Mr. King and Mrs. Jordan in the "Country Girl." R. Smirke, R.A. The drawing is easy and natural, but the colouring appears to us deficient in tone and breadth.

153. View of the River Severn near the New Passage House. Nasmyth. A delightful scene in what we may call the artist's best, or crisp style.

157. Puppy and Frog. E. Landseer, R.A. In the most vigorous style of our best animal painter.

163. A State Quarry. De Loutherbourg.

165—167. Portraits of Worlidge and Mortimer. Painted by themselves.

172. Villa of Maecenas. One of Wilson's most celebrated compositions, of classic fame.

181. Master's Out, "The Disappointed Dinner Party." R.W. Buss. A scene of cockney mortification humorously treated.—An unlucky Londoner and his tawdrily-dressed wife, appeared to have toiled up the hill, with their family of four children, to a friend's cottage, the door of which is opened by an old housekeeper, with "Master's out," while the host himself is peeping over the parlour window-blind at the disappointment of his would-be visitors. The annoyance of the husband at the inhospitable answer, and the fatigue of his fine wife, are cleverly managed; while the mischievous pranks of the urchin family among the borders of the flower-garden remind us of the pleasant "Inconveniences of a Convenient Distance." The colouring is most objectionable; though the flowers and fine clothes are very abundant.

194. Falls of Niagara. Wilson. A sublime picture of this terrific wonder of the world.

196. Erzelin Bracciaferro musing over Meduna, slain by him for disloyalty during his absence in the Holy Land. Fuseli. A composition of touching melancholy, such as none but a master-mind could approach.

199. The late R.W. Elliston, Esq. One of Harlow's best portraits: the likeness is admirable, and the tone well accords with Elliston's unguent, supple expression.

204. Portrait of Dr. Wardrope. Raeburn. This is one of the artist's finest productions: it is clever, manly, and vigorous—painting to the life, without the flattering unction of varnished canvass. The fine, broad, bold features of the sitter were excellently adapted to the artist's peculiar powers.

205. Portrait of Thomson, the Poet. Hogarth. The well-known picture. How fond poets of the last century were of their dishabille in portraits: they had their day as well as nightcaps.

217. Johnny Gilpin. Stothard. This lively composition is well known, as it deserves to be; but it may not so well be remembered that the popularity of John Gilpin was founded by a clever lecturer, who recited the "tale in verse" as part of his entertainment. (See page 367.) What would an audience of the present day say to such puerility; though it would be certainly more rational than people listening to a French play, or an Italian or German opera, not a line of which they understand.

229. Portrait of R.B. Sheridan. The well-known picture, by Reynolds, whence is engraved the Frontispiece to Moore's Life of the Statesman and Dramatist. Here is the "man himsel," in the formal cut blue dress-coat and white waistcoat of the last century. The face may be accounted handsome: the cheeks are full, and, with the nose, are rubicund—Bacchi tincti; the eyes are black and brilliantly expressive;—and the visiter should remember that Sir Joshua Reynolds, in painting this portrait, is said to have affirmed that their pupils were larger than those of any human being he had ever met with. They retained their beauty to the last, though the face did not, and the body became bent. How much it is to be regretted that Sheridan with such fine eyes had so little foresight. There is in the gallery a younger portrait of him, in a stage or masquerade dress, which is unworthy of comparison with the preceding.

231. Scene in Covent Garden Market. One of the best views of the old place, by Hogarth; and one of the last sketches before the recent improvements, will he found in The Mirror, vol. xiii. p. 121. By the way, the pillar and ball, which stood in the centre of the square, and are seen in the present picture, were long in the garden of John Kemble, in Great Russell-street, Bloomshury.

243. Portrait of the late Mr. Holcroft. Dawe. In this early performance of the artist, we in vain seek for the "best looks" of the sitter: such as the painter threw into his portraits of crowned heads.

248. The Happy Marriage. An unfinished picture by Hogarth; yet how beautifully is some of the distant grouping made out;—what life and reality too in the figures, and the whole composition, though seen, as it were, through a mist.

249. Study of a Head from Nature, painted by lamp-light. Harlow. A curious vagary of genius.

258. Daughter of Sir Peter Lely. Lely. We take this to be the oldest picture in the gallery. Lely has been dead upwards of a century and a half.