Полная версия

Полная версияПолная версия:

The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 20, No. 574, November 3, 1832 Title

Under our Saxon ancestors, by whom the Cinque Ports were first chartered, all the havens were open and in good condition, in which state they were found by the Normans, who confirmed to the Ports their ancient privileges. Through several centuries their prosperity continued to increase; the towns were well built, fully inhabited, and in possession of a lucrative and extensive commerce; they had many fine ships constantly employed, and abounded with hardy and intrepid seamen; opulence was visible in their streets, and happiness in their dwellings. But times have sadly changed with them. Let us inquire into the causes which led to their decay. The first cause is the failing of their several havens, some by the desertion of the sea, and others from being choked up by the impetuosity of that boisterous and uncertain element. The second is the change that has taken place in the method of raising and supporting a national marine, now no longer entrusted to the Cinque Ports; and the third was from the invasion of their privileges with respect to trade.

It is evident from their history that the Cinque Ports were once safe and commodious harbours, the decay of which is attributable chiefly to the practice of inning or gaining land from the sea; the first attempts at which were made upon the estuary into which the river Rother discharges itself, between Lydd and Romney. As there were marshes here in the time of the Saxons, and as almost all the property in the neighbourhood belonged to the church, it is most probable that this mischievous practice was first introduced by their clergy. By various operations the river was forced into a new channel, and a very strong fence, called a ree, was built to ensure its perpetual exclusion. The success which attended this operation roused the cupidity of the Archbishops of Canterbury, who considering it as an excellent method for increasing their property, continued to make large and successful inroads on the sea, till the tract of land so gained may be computed at between fifty and sixty thousand acres, now become rich and fertile pastures, producing good rents, and extremely valuable.

Before these encroachments were effected upon the sea, no contention existed between that turbulent element and the shore; but as soon as cupidity made inroads upon its ancient boundary, and declared war against the order of nature, the effects of its impetuous resentment were speedily felt. Whoever supposes he can control old Ocean, or make war upon his ancient border with impunity, will find himself mistaken, and soon discover that he knew little of the perseverance, the genius, or the power of his opponent. It retired from some towns and places where they intended it should remain, and overflowed or washed away others grown rich by its bounty; here it fretted and undermined the shore till it fell, and there it cast up beach and sand, covering a good soil with that which is both disagreeable and useless; and instead of being the source of industry and wealth, it became the engine of destruction and terror. Hastings, Romney, Hythe, Rye, and Winchelsea, with their dependencies, are now totally gone as ports, and greatly diminished in wealth and consequence. Winchelsea was once so large and handsome, that Elizabeth, during one of her progresses, bestowed upon it the appellation of Little London. Hythe formerly contained seven parish churches, now reduced to one. Rye and Romney look as if the plague had been raging through their dull and gloomy streets, and had carried off nearly all the population. Hastings, though still flourishing as a town, owes its prosperity to its having become a fashionable sea-bathing-place; for as to a port or haven, there is not a vestige of one remaining. Thus it will be seen that private individuals, for their own benefit, have been suffered to gain from the sea fifty thousand acres of pasture land, at a cost to the nation of five safe and commodious harbours, and the ruin of their several towns; thus reversing the political maxim, that private interest ought to give way to public benefit.

Similar in state to the five towns just named, is the once-celebrated and commodious port and town of Sandwich, now distant a mile and a half from the sea. This circumstance, also, is not attributable to any natural decline or desertion of the water, but to the long-continued exertions of individuals, for the purpose of gaining land from that estuary which formerly divided Kent from the Isle of Thanet. The estuary is no more, and deplorable are the consequences which have followed its loss; for towns have dwindled into villages, and villages into solitary farm-houses, throughout the entire district through which it flowed; trade and commerce have declined, and population has suffered a most extensive and frightful reduction.

In exchange for the ancient prosperity of this neighbourhood, we have large fens or salt marshes, rich in fertility and malaria; but in this, as in the former contest, the sea has had the best of it; for Bede has clearly expressed in his writings that "the Isle of Thanet was of considerable bigness, containing, according to the English way of reckoning, 600 families." Supposing, therefore, a family or a hide of land to contain only 64 acres, the smallest quantity taken by any author of credit, the quantity of land, at the time he wrote, will amount to 38,400 acres; which, exclusive of the salt marshes, is double the quantity contained in the island at the present time; we have, therefore, lost more land than we have gained, and, most unfortunately, the safe and eligible port of Sandwich into the bargain.

The port of the town of Sandwich, was for centuries one of the best and most frequented in the realm, producing to the revenue of the customs between sixteen and seventeen thousand pounds. But with the decay of her haven, commerce declined, and the revenue became so small, "that it was scarcely sufficent to satisfy the customer of his fee:" a dull and melancholy gloom is now spread through all her streets, and around her walls, where, during the times that her haven was good and her woollen manufactures were prosperous, naught was visible but activity, industry, and opulence. Her sun has been long and darkly eclipsed; but with a little well-directed exertion on the part of her inhabitants, and a moderate expenditure, it might be made to shine again, though not, perhaps, in all the brilliancy of its former splendour.6

Dover, the other port remaining to be noticed, is certainly a flourishing town at present; but to what does it owe its prosperity? Not to any of its advantages as one of the Cinque Ports, but to the circumstances of its being the port of communication with out Gallic neighbours, and to its having become frequented for the purpose of sea-bathing, which latter is a recent event. As a sea-bathing place it is likely it may appear cheerful and gay, even when the Continent is closed against us; but before it became a candidate for the favour of the migratory hordes of the summer months, it was, during the period of a war with France, one of the dullest towns in the kingdom.

The last calamity which I shall notice, is the attack which was made upon their home trade. They were, by their charter, to have full liberty of buying and selling, which privilege was opposed by the citizens of London, who disputed their right to buy and sell freely their woollens in Blackwell Hall. The charter of the ports is one hundred years older than that of London, but, notwithstanding this priority of right, the citizens of London prevailed. The result was indeed calamitous, for after the decay of the haven, the chief source of prosperity to the town of Sandwich consisted in the woollen manufactures, and as the freedom of buying and selling was now denied, the manufacturers immediately removed, and were soon followed by the owners of the trading vessels, and the merchants; and thus basely deprived of those advantages from which arose their ancient opulence and splendour, they sank with rapidity into that insignificance and poverty which have unfortunately remained their inseparable companions up to the present hour. Among the princes who have executed the high and honourable office of Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports, we find the names of the brave and unfortunate Harold, in the time of the Confessor, and Edward, Prince of Wales, in the time of Henry III. Henry V., when Prince of Wales, held this office, which was afterwards filled by Humphry, Duke of Gloucester. James II., when Duke of York, was Lord Warden, as was also Prince George of Denmark, with many other princes of the royal blood. In celebrated names among the nobility, the catalogue of Lords Warden is eminently rich. The family of Fiennes occurs frequently, as does also that of Montfort. Hugh Bigod; several of the family of Cobham, as well as the names of Burghersh, De Grey, Beauchamp, Basset, and De Burgh, are studded over the calendar, in the early reigns. Edward, Lord Zouch, and George, Duke of Buckingham, were Lords Warden in the reign of James I.; since that period the office has been filled by the Duke of Ormond; the Earl of Holdernesse, whose attention to the advantages of the ports was great; Lord North, the late Mr. Pitt, whose affability and condescension, added to a real regard for the prosperity of the Cinque Ports, and an unremitted attention to the duties of the Wardenship, gained him universal esteem; and lastly, by that honest and respected stateman, the late Earl of Liverpool. The mantle of the ports has now fallen on his Grace the Duke of Wellington, than whose name there does not exist a greater in the catalogue of Lords Warden. The public spirit displayed by the Duke, since his wardenship, cannot be too widely known, nor too highly applauded,—his grace having paid into the Treasury, for the public service, the whole amount of the proceeds of his office, as Lord Warden, thus furnishing a noble example of magnanimity and disinterestedness.

DRYBURGH ABBEY

[The clever stanzas transferred from a late number of the Literary Gazette to No. 572 of the Mirror, are from the spirited pen of Mr. Charles Swain: they are the most poetical and appropriate of the tributes yet inscribed to the memory of Sir Walter Scott, although this is but mean praise compared with their merit. In the Gazette of Saturday last, the following additions are suggested by two different correspondents, "though," as the editor observes, "they are offered with great modesty by their authors."]

And after these, with hand in hand, the Sisters Troil appear;Poor "Mina's" cheek was deadly pale, in "Brenda's" eye a tear;And "Norna," in a sable vest, sang wild a funeral cry,And waved aloft a bough of yew, in solemn mystery."George Heriot" crap'd, and "Jenkin Vin" with prentice-cap in hand—Ev'en "Lady Palla" left her shrine to join that funeral band;But hood and veil conceal'd her form—yet, hark! in whisper's toneShe breathes a Christian's holy prayer for the mighty spirit flown.A wail!—a hollow, churchyard wail!—a wild weird-sister's cry!—Ah! "Annie Winnie," thou too here?—and "Alice?"—vanish—fly!"Not so," they shrieked, "we'll see the corse—the bonny corse; 'twas meet—And pity 'twas we were not there to bind his winding sheet."Old "Owen" passed with tottering step, and lost and wandering looks;"He's balanced his account," he cried, "and closed his earthly books;"Bold "Loxley," with his bow unbent—unhelm'd "Le Belafré,"Together pass'd—the archer wiped one silent tear away.Stern "Bridgenorth," with his daughter's arm hung on his own, stalk'd by;The blushing "Alice" veils her face from "Julian Peveril's" eye:"Alack-a-day," 'Daft Davie' cries—"come, follow, follow me,We'll strew his grave with cowslip buds and blooming rosemary."In distance from the mournful throng, like stars of other spheres,The lovely "Mary Stuart" pays the homage of her tears,With "Cath'rine Seymore" at the shrine of Scotia's dearest name,And with her bends the "Douglas'" knees, with bold young "Roland Graeme."But hark! what fairy melody comes wafted on the gale—Oh! 'tis "Fenella's" sighing lute, in notes of woe and wail:"Claud Halero" catches at the strain, and mourns the minstrel gone,"His spirit rest in peace where sleeps the shade of glorious John!"With spattered cloak, the ladies' knight, the gallant "Rawleigh" see,"Sir Creveceux's" plume waves by his side, and "Durward's" fleur-de-lis;There "Janet" leans on "Foster's" arm—e'en "Varney's" treacherous eyeIs moistened with a tear that speaks remorse's agony.Next, muffled in his sable cloak, "Tressilian" wends his way,His slouching hat denies his brow the cheering light of day;See how he dogs the proud earl's steps, as "Leicester" bears alongThe lovely "Amy" on his arm through that sad mournful throng.There "Lillias" pass'd with fairy step, in hood and mantle green,Her sire, "Redgauntlet's" eagle eye is fixed on her, I ween;And "Wandering Willie" doffs his cap, to raise his sightless eyeTo Heaven, and cried, "God rest his soul in yonder sunny sky!"Here "Donald Lean," with fillibeg and tartan-skirted knee;There pale was "Cleveland," as he slept by Stromness' howling sea;With faltering step crept "Trapbois" by, with drooping palsied head,More like a charnel truant stray'd from regions of the dead.And thus they pass, a mournful train, the "squire," the "belted knight,"The "hood and cowl," the ladies' page, and woman's image bright;In distance now the solemn notes their requiem's chant prolong,And now 'tis hush'd—to other ears they bear their funeral song."Two beauteous sisters, side by side, their wonted station kept;The dark-eyed 'Minna' look'd to Heaven, the gentle 'Brenda' wept;Wild 'Norna,' in her mantle wrapp'd, with noiseless step mov'd on,'Claud Halcro' in his grief awhile forgot e'en glorious 'John.'The princely 'Saladin' appear'd, aside his splendour laid,And only by his graceful mien and piercing glance betray'd;The lofty 'Edith,' followed by the silent 'Nubian slave,'Dropp'd lightly, as she pass'd, a wreath upon the poet's grave."THE TOPOGRAPHER

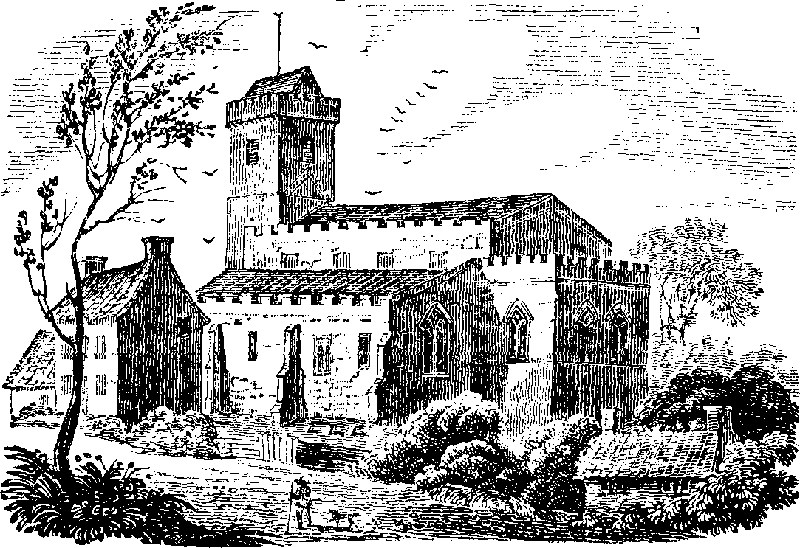

LESTINGHAM CHURCH

(From a Correspondent.)Lestingham, which is supposed to signify lasting-home, is a village near Kirkby Moorside, Yorkshire, the scene of Buckingham's death, so caricatured by Pope in his Dunciad. It is remarkable on account of its church, which is a most interesting edifice to the antiquary, exhibiting a true specimen of Saxon architecture. The east end terminates in a semicircular recess for the altar, resembling the tribune of the Roman basilica. It was here that Cedd, bishop of the East Saxons, or London, founded a monastery for Benedictines, about the year 648, or, some say, 655. The church of Lestingham was the first which was built in this district, or the first of which we have any account. It was originally constructed of wood, and it was not till many years after that a stone one was erected.

Cedd was a Saxon missionary, educated at the monastery of Lindisfarne, now Holy Island, not far from Bamburgh, the capital of Bernicia. Ethelwald, king of Deira, knowing Cedd to be a man of real piety, desired him to accept some land for the building of a monastery, at which the king might attend to pray. Cedd availed himself of the proposal, and chose Lestingham. Having fixed on the spot for the site of the sanctuary, he resolved to consecrate it by fasting and prayer all the Lent; eating nothing except on the Lord's day, until evening; and then only a little bread, an egg, and a small quantity of milk diluted with water; he then began the building. He established in it the same discipline observed at Lindisfarne. Cedd governed his diocese many years; and died of a plague, when on a visit to his favourite monastery at Lindisfarne, where he had been ordained bishop by Finan; he was interred here, 664, but his remains were taken up, and re-interred in the present church, on the right side of the altar.

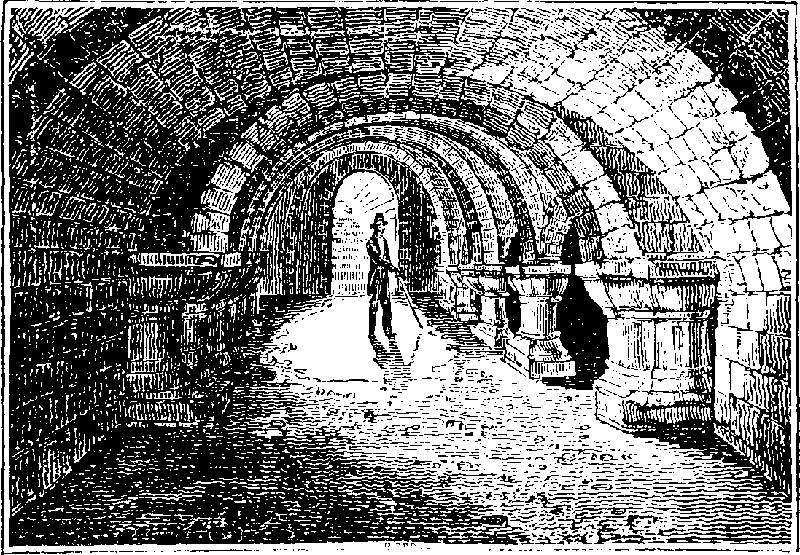

The present Saxon church contains many relics of antiquity; as painted glass, ancient inscriptions, &c.; but the most remarkable feature of is interior is the celebrated crypt, or vault, formerly used as a depository for the venerated relics of canonized prelates. At the east end of this subterraneous retreat, from the window through which the light faintly gleams, the scene is interesting to astonishment. Here you perceive the massy arches ranged in perspective on huge cylindrical pillars, with variously sculptured capitals, each differing from the other, and all in the real Saxon style; to this add the groined roof, and the stairs at the west end, leading up into the church, enveloped in a luminous obscurity, from the scanty light admitted by the window at the east end. From the account given by Venerable Bede, that the body of Cedd was interred on the right of the altar, we may suppose that the crypt was built after the erection of the church, though the time cannot be ascertained.

About fifty years ago, the remaining part of the venerable monastery, founded by Cedd, was razed, and its walls, hallowed by the dust of the holy brotherhood, furnished materials for building. The Rev. W. Ellis, the then incumbent, whose indignation, at the circumstance, was unbounded, wrote some Latin verses on the subject; but they have been lost in the stream of time, and, like the ashes of the hand that wrote them, cannot be found.

The late Mr. Jackson, R.A., was a native of the village of Lestingham; and, with feelings of regard for the land of his childhood, he proposed to execute a painting, as an altar-piece for the church. His Grace the archbishop of York and the Rev. F. Wrangham, were consulted on the subject, and gave it their approval; but, we believe, the meritorious artist died before he had finished the painting.

NEW BOOKS

WILD SPORTS OF THE WEST

This book is a grievous failure—that is, if the merits of books are to be adjudged with their titles. The writer is the author of Stories of Waterloo, from whom better things might have been expected. He has taken for his model, Mr. Lloyd's really excellent Field Sports of the North of Europe; but he has woefully missed his mark. The title of the work before us is equivocal: a reader might as reasonably expect the Sports of the Western World, as adventures in Ireland, such as make up the present volumes. What we principally complain of is the paucity of Sports among their contents. It is true that the title also promises Legendary Tales and Local Sketches, but here they are the substance, and the Wild Sports mere shadow. We have too little of "the goodly rivers," "all sorts of fish," "the sweet islands and goodly lakes, like little inland seas," "of the most beautiful and sweet countrey," as Spenser phrases it in the author's title-page; and there is not so much as the author promises in his preface, of shooting the wild moors and fishing the waters, of days spent by "fell and flood," and light and joyous nights in mountain bivouacs and moorland huts. There is too much hearsay, and storytelling not to the purpose, and trifling gossip of "exquisite potatoes" and "rascally sherry"—details which would disgrace a half-crown guide book, and ought certainly not to be set forth with spaced large type in hotpressed octavos at a costly rate. Nevertheless, the work may suit club-room tables and circulating libraries, though it will not be allowed place for vivid display of Wild Sports. We quote two extracts—one, a narrative which the author knows to be substantially true; the other, relating to the attack of eagles, (though we omit the oft-told tale of the peasant attempting to rob an eagle's nest, and his hair turning white with fright):—

The Blind SealAbout forty years ago a young seal was taken in Clew Bay, and domesticated in the kitchen of a gentleman whose house was situated on the sea-shore. It grew apace, became familiar with the servants, and attached to the house and family; its habits were innocent and gentle, it played with the children, came at its master's call, and, as the old man described him to me, was "fond as a dog, and playful as a kitten."

Daily the seal went out to fish, and after providing for his own wants, frequently brought in a salmon or turbot to his master. His delight in summer was to bask in the sun, and in winter to lie before the fire, or, if permitted, creep into the large oven, which at that time formed the regular appendage of an Irish kitchen.

For four years the seal had been thus domesticated, when, unfortunately, a disease, called in this country the crippawn—a kind of paralytic affection of the limbs which generally ends fatally—attacked some black cattle belonging to the master of the house; some died others became infected, and the customary cure produced by changing them to drier pasture failed. A wise woman was consulted, and the hag assured the credulous owner, that the mortality among his cows was occasioned by his retaining an unclean beast about his habitation—the harmless and amusing seal. It must be made away with directly, or the crippawn would continue, and her charms be unequal to avert the malady. The superstitious wretch consented to the hag's proposal; the seal was put on board a boat, carried out beyond Clare Island, and there committed to the deep, to manage for himself as he best could. The boat returned, the family retired to rest, and next morning a servant awakened her master to tell him that the seal was quietly sleeping in the oven. The poor animal over night came back to his beloved home, crept through an open window, and took possession of his favourite resting-place.

Next morning another cow was reported to be unwell. The seal must now be finally removed; a Galway fishing-boat was leaving Westport on her return home, and the master undertook to carry off the seal, and not put him overboard until he had gone leagues beyond Innis Boffin. It was done—a day and night passed; the second evening closed—the servant was raking the fire for the night—something scratched gently at the door—it was of course the house-dog–she opened it, and in came the seal! Wearied with his long and unusual voyage, he testified by a peculiar cry, expressive of pleasure, his delight to find himself at home, then stretching himself before the glowing embers of the hearth he fell into a deep sleep.

The master of the house was immediately apprized of this unexpected and unwelcome visit. In the exigency, the beldame was awakened and consulted; she averred that it was always unlucky to kill a seal, but suggested that the animal should be deprived of sight, and a third time carried out to sea. To this hellish proposition the besotted wretch who owned the house consented, and the affectionate and confiding creature was cruelly robbed of sight, on that hearth for which he had resigned his native element! Next morning, writhing in agony, the mutilated seal was embarked, taken outside Clare Island, and for the last time committed to the waves.

A week passed over, and things became worse instead of better; the cattle of the truculent wretch died fast, and the infernal hag gave him the pleasurable tidings that her arts were useless, and that the destructive visitation upon his cattle exceeded her skill and cure.

On the eighth night after the seal had been devoted to the Atlantic, it blew tremendously. In the pauses of the storm a wailing noise at times was faintly heard at the door; the servants, who slept in the kitchen, concluded that the Banshee came to forewarn them of an approaching death, and buried their heads in the bed-coverings. When morning broke the door was opened—the seal was there lying dead upon the threshold!"

"Stop, Julius!" I exclaimed, "give me a moment's time to curse all concerned in this barbarism."

"Be patient, Frank," said my cousin, "the finale will probably save you that trouble. The skeleton of the once plump animal—for, poor beast, it perished from hunger, being incapacitated from blindness to procure its customary food—was buried in a sand-hill, and from that moment misfortunes followed the abettors and perpetrators of this inhuman deed. The detestable hag, who had denounced the inoffensive seal, was, within a twelvemonth, hanged for murdering the illegitimate offspring of her own daughter. Every thing about this devoted house melted away—sheep rotted, cattle died, 'and blighted was the corn.' Of several children none reached maturity, and the savage proprietor survived every thing he loved or cared for. He died blind and miserable.