Полная версия

Полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 20, No. 573, October 27, 1832

Fielding was a contemporary member of the home-circuit, with Sergeant Bond and myself. In the performance of the duties of conviviality, over which the learned sergeant, as head of the circuit, presided, he found in Fielding a powerful auxiliary. He was the son of the author of Tom Jones, and inherited to a great degree the wit and talents of his father.

As a companion, Fielding was invariably pleasant and inimitably entertaining. His conversation abounded with anecdotes, of which he had an inexhaustible fund: his great stock was of Irish stories which he gave with great truth and humour.

I have repeatedly heard him say, that the lowest class of the Irish had more native humour than any other body of people in the same rank in life. He would then relate, in proof of it, the event of a bet which was made on the subject at one of the club-houses in St. James's Street, which then was crowded with English and Irish chairmen, and which was to be decided by the reply of one of each country to the same question. It was, "If you were put naked on the top of St. Paul's, what would you be like?" The English chairman was first called in, and the question being put to him, he ran sulky, and refused to give any direct answer, saying they were making fun of him. Pat was then introduced, and the question being propounded to him: "What should I be like?" says he; "why, like to get could, to be sure, your honours." "This," says he, "they call mother wit; and the most illiterate have a quickness in parrying the effect of a question by an evasive answer. I recollect hearing Sir John Fielding giving an instance of this, in the case of an Irish fellow who was brought before him when sitting as a magistrate at Bow Street. He was desired to give some account of himself, and where he came from. Wishing to pass for an Englishman, he said he came from Chester. This he pronounced with a very rich brogue, which caught the ears of Sir John. 'Why, were you ever in Chester?' says he. 'To be sure, I was,' said Pat; 'wasn't I born there?' 'How dare you,' said Sir John Fielding, 'with that brogue, which shows that you are an Irishman, pretend to have been born in Chester.' 'I didn't say I was born there,' says he; 'I only asked your honour whether I was or not.'"

Fraser's Magazine.

THE NATURALIST

NUTRIA FUR

[We quote the following account of Nutria from the Dictionary of Commerce, by Mr. Macculloch, who believes it to be the first description that has appeared in any English work, and acknowledges it from the pen of J. Broderip, Esq., F.R.S., &c.]

Nutria, or Neutria, the commercial name for the skins of Myopotamus Bonariensis (Commerson,) the Coypou of Molina, and the Quoiya of D'Azara. In France, the skins were, and perhaps still are, sold under the name of racoonda; but in England they are imported as nutria skins—deriving their appellation, most probably, from some supposed similarity of the animal which produces them, in appearance and habits, to the otter, the Spanish name for which is nutria. Indeed, Molina speaks of the coypou as a species of water rat, of the size and colour of the otter.

Nutria fur is largely used in the hat manufacture; and has become, within the last fifteen or twenty years, an article of very considerable commercial importance. From 600,000 to 800,000 skins, principally from the Rio de la Plata, are now annually imported into Great Britain. It is also very extensively used on the continent. Geoffroy mentions, that in certain years, a single French furrier (M. Bechem,) has received from 15,000 to 20,000 skins.

The coypou or quoiya is a native of South America, very common in the provinces of Chili, Buenos Ayres, and Tucuman, but more rare in Paraguay. In size it is less than the beaver, which it resembles in many points. The head is large and depressed, the ears small and rounded, the neck stout and short, the muzzle sharper than that of the beaver, and the whiskers very long and stiff. There are, as in the beaver, two incisor teeth, and eight molar, above and below—twenty teeth in all. The limbs are short. The fore feet have each five fingers not webbed, the thumb being very small: the hind feet have the same number of toes; the great toe and three next toes being joined by a web which extends to their ends, and the little toe being free, but edged with a membrane on its inner side. The nails are compressed, long, crooked, and sharp. The tail, unlike that of the beaver, is long, round, and hairy; but the hairs are not numerous, and permit the scaly texture of the skin in this part to be seen. The back is of a brownish red, which becomes redder on the flanks: the belly is of a dirty red. The edges of the lips and extremity of the muzzle are white.

Like the beaver, the coypou is furnished with two kinds of fur; viz. the long ruddy hair which gives the tone of colour, and the brownish ash-coloured fur at its base, which, like the down of the beaver, is of such importance in hat-making, and the cause of the animal's commercial value.

The habits of the coypou are much like those of most of the other aquatic rodent animals. Its principal food, in a state of nature, is vegetable. It affects the neighbourhood of water, swims perfectly well, and burrows in the ground. The female brings forth from five to seven; and the young always accompany her.

The coypou is easily domesticated, and its manners in captivity are very mild.

NOTES OF A READER

RECORDS IN THE TOWER OF LONDON

(From the Edinburgh Review, just published.)[These stores are of invaluable interest, particularly with reference to the earlier and most obscure portions of our history.]

An immense collection of royal letters and state papers, miscellaneous rolls relating to the revenue, expenditure, debts and accounts of the Crown, New Year's gifts, the royal household, mint, foreign bills of exchange, military and naval affairs, instruments relating to treaties, truces, and infractions of peace, chiefly between England and France; mercantile matters, foreign possessions of the Crown, proceedings in the Admiralty, military and other courts of the great officers of the Crown, pardons, protections, petitions, subsidy rolls, Scotch homage rolls, pardon rolls, privy seals, signet bills, writs of various descriptions from Edward I. to Edward IV., exist there, without calendar or index; and in such masses as to defy the patience of any inquirer, however ardent. It need not be said that in such a variety of documents their value must vary considerably, or that many of them are of little use; but each of them is at least worthy of being examined; and there are few of them which, if properly scrutinized by apt labourers, would not at least contribute to the elucidation or ratification of some branch of history. Some of them would render still more important services; and, by pointing out the daily habits and most familiar occurrences of the lives of our kings and other eminent personages who figure in our history, lead us to a much more accurate estimate of their genius than any that has hitherto been formed. With this view, the close rolls are amongst the most minute and interesting of those documents which remain unexplored. The character of King John has had but scanty justice done to it; and perhaps those who have formed their notions of that monarch from the ordinary accounts of him, will be surprised to find him writing to the Abbot of Reading to acknowledge the receipt of "six volumes of books, containing the whole of the Old Testament, Master Hugh de St. Victor's treatise on the Sacraments, the Sentences of Peter Lombard, the Epistles of St. Augustine on the City of God, and on the 3rd part of the Psalter, Valerian de Moribus, Origen's treatise on the Old Testament, and Candidus Arianus to Marius;"—and that on another occasion shortly afterwards he acknowledges the receipt of "his copy of Pliny," which had been in the custody of the same Abbot. Still less does it consist with the commonly adopted notions of his selfish tyranny, that he should address Bryan de Insula in terms like the following: "Know that we are quite willing that our chief barons, concerning whom you wrote to us, may hunt while passing through your bailiwick, provided that you know who they are and what they take; for we do not keep our forests, nor our beasts, for our own use only, but for the use also of our faithful subjects. See, however, that they are well guarded on account of robbers, for the beasts are more frightened by robbers than by the aforesaid barons." Of the reign of Henry III. the particulars are still more minute. Notwithstanding its connexion with superstitions which exist no longer, we may sympathize with the pious charity that suggested that monarch's order "for feeding as many poor persons as can enter the greater and lesser hall at Westminster on Friday next after the octaves of St. Matthew, being the anniversary of Eleanor, the King's sister, formerly Queen of Scotland, for the good of the said Eleanor's soul." His taste for the fine arts, and his encouragement of its professors, are frequently to be traced in the entries upon these rolls. In one of them he gives directions for having the great chamber at Westminster painted with a good green colour after the fashion of a curtain; and in the great gable of the same chamber near the door this device to be painted,—"Ke ne dune ke ne tine, ne prent ke desire;" and another runs thus,—"The King, in presence of Master William the painter, a monk of Westminster, lately at Winchester, contrived and gave orders for a certain picture to be made at Westminster in the wardrobe where he was accustomed to wash his face, representing the King who was rescued by his dogs from the seditions which were plotted against that King by his subjects, respecting which same picture the King addressed other letters to you Edward of Westminster. And the King commands Philip Lavel his treasurer, and the aforesaid Edward of Westminster, to cause the same Master William to have his costs and charges for painting the aforesaid picture without delay; and when he shall know the cost, he will give them a writ of liberate therefor." For the illustration of the elder historians, and as a means of ascertaining how far narrations of events which appear doubtful or improbable, are correct, these and other buried documents possess great value. That blackest charge against the memory of King John, by which he is implicated in the murder of his nephew Prince Arthur, has been brought forward in forms so various, that common charity has induced many men to withhold their credence from an accusation which rests on vague and uncertain traditions. It is said, however, that Arthur's death, by whatever means it was brought about, took place at Rouen; it has been ascertained very lately for the first time, by inspection of the attestations of records, that John was at that place on that day; a circumstance not in itself enough to lead men to a very violent suspicion of his guilt, if the manner of the Prince's death had not been sudden and mysterious; but which, bringing the charge at least somewhat nearer, may probably lead to further discoveries. Of less importance, but yet not without interest,—if it be interesting to know accurately the early manners of a people, and to trace their progress from periods when those lights of science which are now beaming in full radiance over the land, had just begun to glimmer above the horizon,—is the following instance. Matthew Paris relates, that in 1255, an elephant was sent by the King of France to Henry III., and that it being the first animal of that species that had been seen in England, the people flocked in great numbers to behold it. Upon the close rolls is entered a writ tested at Westminster the 3rd of February, 39, H. III. (1255,) directing the sheriff of Kent to "go in person to Dover, together with John Gouch, the King's servant, to arrange in what manner the King's elephant, which was at Whitsand,12 may best and most conveniently be brought over to these parts, and to find for the same John a ship and other things necessary to convey it; and if, by the advice of the mariners and others, it could be brought to London by water," directing it to be so brought. That the stranger arrived safely, is evident from a similar writ, dated the 23rd of the same month, commanding the Sheriffs of London to "cause to be built at the Tower of London, a house forty feet in length and twenty in breadth, for the King's elephant." Economy however, it seems, was not neglected by the monarch in his menus plaisirs; for the Sheriffs are expressly charged to see that the house be so strongly constructed that, whenever there should be need, it might be adapted to and used for other purposes; and the costs are to be ascertained "by the view and testimony of honest men."

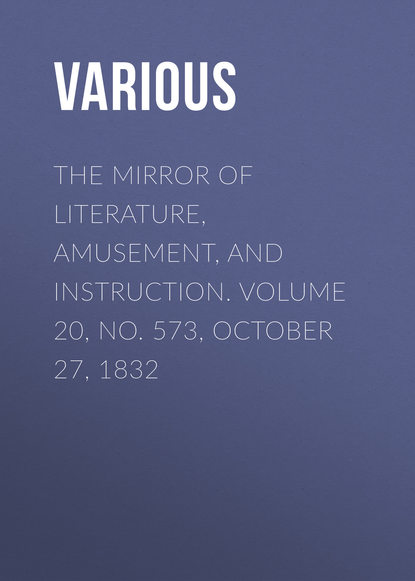

ZOOLOGICAL GARDENS, REGENT'S PARK

(Continued from page 201.)Returning from the Elephant's Stable and Enclosure, we pass the shed and enclosure for Ostriches. Here are fine specimens of the African Ostrich, distinguished by their black plumage, and sent from Tripoli, by Hanmer Warrington, Esq., and a fine female bird from the collection of the late Marchioness of Londonderry. The general colour of the feathers of the female is ashy-brown, tipped with white; and the exquisitely white plumes so much prized are obtained from beneath the wings and tail of both sexes.13

Ostriches.

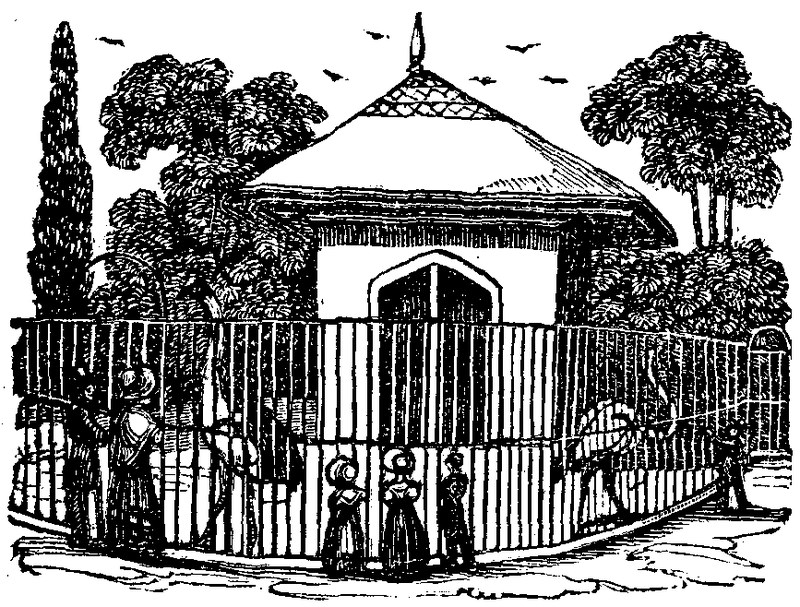

Retracing our steps to the Southern Garden we find several buildings unnoticed; as a large Aviary, appropriated to various birds, but usually to those of rare description.

Aviary.

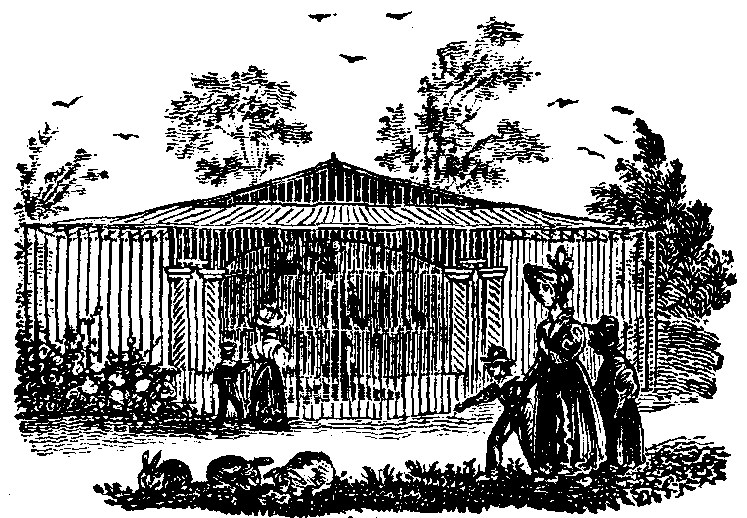

The slope or valley in the garden, between the terrace and the Park road, is partly occupied by a Pond and Fountain, where are Swans and other swimming birds. In the distance of the cut is seen the principal aviary, where are some of the finest birds in the garden, as varieties of Cranes, Storks, Herons, Spoonbills, Curassows, and the revered bird of the ancients—the splendid scarlet Ibis.

Pond and Fountain.

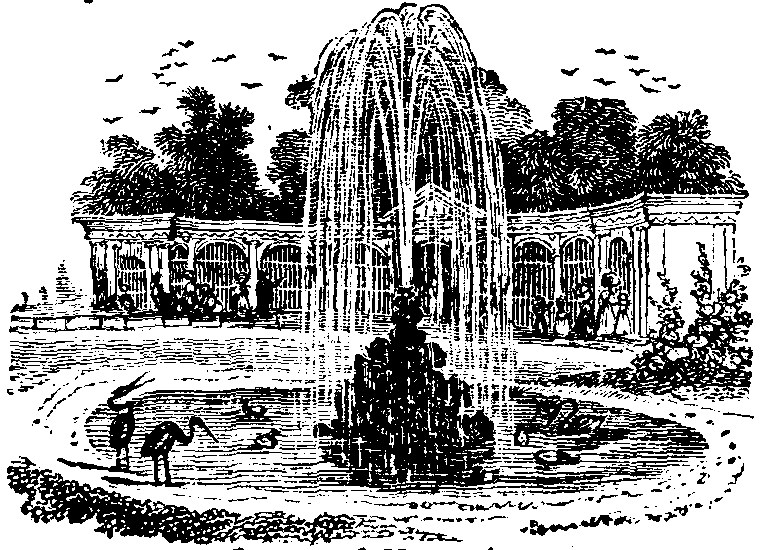

As you return by the main path to the terrace, opposite the Llama House is a large octagon summer cage for Maccaws where red and yellow, blue and yellow, and red and blue species, are usually kept; with cockatoos. In winter they are removed to some of the warmer repositories.

Maccaws.

It gives us great pleasure to hear that the Commissioners of Woods and Forests have in consequence of an application made to them by the Zoological Society, granted an extensive piece of land, on the northern verge of Regent's Park, to be added to the Gardens. It will be speedily laid out in walks and shrubberies, and in habitations for the numerous animals for which the society have at present little room, and has, in fact, caused the application for the grant. It is also in contemplation to erect a superb Museum on part of it, and to remove the Society's present one from Bruton-street.

GERMAN WINES

Nassau is rich in mineral waters, and richer in generous wines—its Johannesberger, Hockheimer, Rudesheimer, Markbrenner, Asmanshäuser, Steinberger, Shiersteiner, &c. are the most noble juice of the grape. The Steinberger, in the mark of Hottenheim, belongs to the Court exclusively. In 1811 the cask (Stückfass,) containing 7-1/2 sums, equal to 600 measures, or 1,200 bottles, was sold for 6,000 florins, and at Wisbaden a common green bottle-full sells at a ducat, or 9s. 6d. sterling. From Mentz to Coblentz the German Bacchus has pitched his throne on the territory and soil of Nassau.

Letter from Germany, in the Morning Herald.

NEW BOOKS

[THE FORGET-ME-NOT,

The first-born of the Annuals, comes to woo us with the kindred charms of poetry and playful humour—romance and real life—full of kindly feelings, sighs and tears, such as Niobe shed, and smiles that with their witchery light up the finest affections to cherish drooping nature, and guide our footsteps along this world of weal and woe. To be more explicit, the character of the present volume is well told by Mr. Haynes Bayly in its second page:—

a gift that friend to friendAt parting will deliver;And love with his own name will blendThe dear name of the giver.So pure, so blameless is this book,That wise and wary sagesWill lead young Innocence to lookUpon its tasteful pages.We can only particularize a few of the most striking papers. Among the metrical gems is Conradin, a fine battle-piece, by Mr. Charles Swain; an Every-day Tale, by Montgomery—one of "the short and simple annals of the poor," written in behalf of a Society for relieving distressed females in the first month of their widowhood, to save their little households from being broken up before they can provide means for their future maintenance: and Far-off Visions, by Mary Howitt. The prose gem of the volume, to our taste, is

Giulietta, a Tale of the Fourteenth Century, by L.E.L.,

which we abridge. The scene lies at Genoa, where Giulietta Aldobrandini, being at the point of death, commits her three daughters to the care of their uncle the Cardinal Aldobrandini. The Countess dies, and the three girls, Constanza, Bianca, and Giulietta, having sprung up into graceful womanhood, arrive at the Cardinal's palace.]

It was early in a spring evening when the Aldobrandini arrived at their uncle's dwelling. It was an old and heavy-looking building. Constanza and Bianca, as the massy gate swung behind them, on their arrival in the dark, arched court, simply remarked that they were afraid it would be very dull: but Giulietta's imagination was powerfully impressed; a vague terror filled her mind, which the gloom of the huge and still chambers through which they were ushered did not tend to decrease. At length, they paused in a large vaulted room, while the aged domestic went on, to announce them to the cardinal. Giulietta glanced around: the purple hangings were nearly black with age, so was the furniture, while the narrow windows admitted shadows rather than light. Some portraits hung on the walls, all dignitaries of the church; but the colour of their scarlet robes had faded with time, and each wan and harsh face seemed to turn frowning on the youthful strangers. A door opened, and they were ushered into the presence of their uncle. He was standing by a table, on which was a crucifix and an open breviary, while a volume of the life of St. Chrysostom lay open on the floor. A window of stained glass was half screened by a heavy curtain, and the dark panels of carved oak added to the gloom of the oratory. The sisters knelt before him, while gravely and calmly he pronounced over them a welcome and a blessing. Constanza and Bianca received them gracefully and meekly, but Giulietta's heart was too full; she thought how different would have been the meeting had they been but kneeling before parents instead of the stern prelate. She bowed her head upon the breviary; and her dark hair fell over her face while she gave way to a passionate burst of tears. Next to indulging in the outward expression of feeling himself, the cardinal held it wrong to encourage it in another. Gently, but coldly, he raised the weeping Giulietta; and, with kind but measured assurances of his regard and protection, he dismissed the sisters to their apartment. Could Giulietta have known the many anxious thoughts that followed her, how little would she have doubted her uncle's affection!

The light of a few dim stars shed a variable gleam amid the thick boughs of a laurel grove, too faint to mark the objects distinctly, but enough to guide the steps of one who knew the place. The air was soft and warm, while its sweetness told of the near growth of roses; but a sweeter breath than even the rose was upon the air, the low and musical whisper of youth and of love. Gradually, two graceful forms became outlined on the dark air—the one a noble-looking cavalier, the other Giulietta. Yet the brow of the cavalier was a gloomy one to turn on so fair a listener in so sweet a night; and his tone was even more sad than tender.

"I see no hope but in yourself. Do you think my father will give up his life's hatred to the name of Aldobrandini, because his son loves one of its daughters, and wears a sad brow for a forbidden bride? or, think you, that yonder stern cardinal will give up the plans and power of many years, and yield to a haughty and hereditary foe, for the sake of tears even in thy eyes, Giulietta?"

"I know not what I hope," replied the maiden, in a mournful, but firm voice; "but this I know, I will not fly in disobedience and in secrecy from a home which has been even as my own."

"And what," exclaimed the cavalier, "can you find to love in your severe and repelling uncle?"

"Not severe, not repelling, to me. I once thought him so; but it was only to feel the more the kindness which changed his very nature towards us. My uncle resembles the impression produced on me by his palace: when I first entered, the stillness, the time-worn hangings, the huge, dark rooms, chilled my very heart. We went from these old gloomy apartments to those destined for us, so light, so cheerful, where every care had been bestowed, every luxury lavished; and I said within myself, 'My uncle must love us, or he would never be thus anxious for our pleasure.'"

A few moments more and their brief conference was over. But they parted to meet again; and at length Giulietta fled to be the bride of Lorenzo da Carrara. But she fled with a sad heart and tearful eyes; and when, after her marriage, every prayer for pardon was rejected by the cardinal, Giulietta wept as if such sorrow had not been foreseen. Her uncle felt her flight most bitterly. He had watched his favourite niece, if not with tenderness of look and tone, yet with deep tenderness of heart. When her elder sisters married and left his roof, he missed them not: but now it was a sweet music that had suddenly ceased, a soft light that had vanished. The only flower that, during his severe existence, he had permitted himself to cherish, had passed away even from the hand that sheltered it. It was an illusion fresh from his youth: his love for the mother had revived in a gentler and holier form for her child, and now that, too, must perish. He felt as if punished for a weakness; and all Giulietta's supplications were rejected: for pride made his anger seem principle. "I have been once deceived," said he; "it will be my own fault if I am deceived again."

Yet how tenderly was his kindness remembered, how bitterly was his indignation deplored, by the youthful Countess da Carrara!—for such she now was—Lorenzo's father having died suddenly, soon after their union. The period of mourning was a relief; for bridal pomp and gaiety would have seemed too like a mockery, while thus unforgiven and unblessed by one who had been as a father in his care. At her earnest wish they fixed their first residence in the marine villa where her mother died.

"And shall you not be sad, my Giulietta?" asked her husband. "Methinks the memory of the dead is but a mournful welcome to our home."

"Tender, not mournful," said she. "I do believe that even now my mother watches over her child, and every prayer she once breathed, every precept she once taught, will come more freshly home to my heart, when each place recalls some word or some look there heard and there watched. It is for your sake, Lorenzo, I would be like my mother."

They went to that fair villa by the sea; and pleasantly did many a morn pass in the large hall, on whose frescoed walls was painted the story of Oenone, she whom the Trojan prince left, only to return and die at her feet. On the balustrade were placed sweet-scented shrubs, and marble vases filled with gathered flowers; and, in the midst, a fountain, whose spars and coral seemed the spoil of some sea-nymph's grotto, fell down in a sparkling shower, and echoed the music of Giulietta's lute. Pleasant, too, was it in an evening to walk the broad terrace which overlooked the ocean, and watch the silver moonlight reflected on the sea, till air and water were but as one bright element.