Полная версия

Полная версияПолная версия:

The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 20, No. 569, October 6, 1832

On the 22nd of August the sheriffs waited on the Lord Mayor at Guildhall, "and from thence went in procession to Smithfield, with city officers and trumpets to proclaim Bartholomew Fair." On the 2nd of September, "this day being kept solemn in commemoration of the fire of London," they went to St. Paul's in their "black gowns, and no chains, and heard a sermon on the said occasion." On the 8th of September the sheriffs waited on the Lord Mayor, in procession, "the city music going before, to proclaim Southwark Fair, as it is commonly called, although the ceremony is no more than our going in our coaches through the Borough, and turning round by Saint George's church, back again to the Bridge House; and this to signify the license to begin the fair." The journalist adds:—"On this day the sword-bearer wears a fine embroidered cap, said to have been worked and presented to the city by a monastery."

"Monday, September 21st, being St. Matthew's Day, waited on my Lord Mayor to the great hall in Christ's Hospital, where we were met by several of the presidents and governors of the other hospitals within the city; and being seated at the upper end, the children passed two by two, whom we followed to the church, and after hearing a sermon, came back to the grammar school, where two boys made speeches in commemoration of their benefactors, one in English, the other in Latin; to each of whom it is customary for the Lord Mayor to give one guinea, and the two sheriffs half-a-guinea a piece, as we did. Afterwards, the clerk of the hospital delivered to the Lord Mayor a list of the several governors to the several hospitals nominated the preceding year. Then the several beadles of all the hospitals came in, and laying down their staves on the middle of the floor, retired to the bottom of the hall. Thereupon the Lord Mayor addressed himself to the City Marshal, enquiring after their conduct, and if any complaint was to be made against any one in particular; and no objection being made, the Lord Mayor ordered them to take up their staves again: all which is done in token of their submission to the chief magistrate, and that they hold their places at his will, though elected by their respective governors. We were afterwards treated in the customary manner with sweet cakes and burnt wine."

The shrievalty of Mr. Hoare, and his brother officer, expired on the 28th of September, and about seven o'clock in the evening the indentures with the new sheriffs were executed at Guildhall, "and the charge of the gaols and all other trusts relating to this great and hazardous, though otherwise honourable, employment, delivered over to them. And after being regaled with sack and walnuts, I returned to my own house in my private capacity, to my great consolation and comfort."

In concluding this account of a manuscript, which illustrates so many of the customs and privileges of the city, it should be mentioned that it includes various notices of the treats or dinners which the Lord Mayor and the sheriffs give by turns to the judges, sergeants, &c. at the beginning and end of the respective terms; as well as of the manner of delivering petitions to the House of Commons, which is generally done by the sheriff; the city having a right to present petitions by an officer of its own, and without the intervention of any member.

THE NATURALIST

THE NIGHTINGALE

The nightingale is universally admitted to be the most enchanting of warblers; and many might be tempted to encage the mellifluous songster, but for the supposed difficulty of procuring proper food for it. In the village of Cossey, near Norwich, an individual has had a nightingale in cage since last April; it is very healthy and lively, and has been wont to charm its owner with its sweet and powerful strains. The bird appears about two years old: it has gone through this year's moulting. It is kept in a darksome cage, with three sides wood, and the fourth wired. The bottom of the cage is covered with moss. Its constant food is a paste, which is composed of fresh beef or mutton, scraped fine with a knife, and in equal portions mixed with the yolk of an egg boiled hard. The owner, however, about once a-day, gives it also a mealworm; he does not think this last dainty to be necessary, but only calculated to keep the nightingale in better spirits. The paste should be changed before it becomes sour and tainted.

PHILOMELOS.NOTES

Abridged from the Magazine of Natural HistorySilkworm.—(By a Correspondent.)—It has occurred to me, and I have not seen it remarked elsewhere, as a striking and interesting peculiarity of this insect, that it does not wander about as all other caterpillars do, but that it is nearly stationary in the open box or tray where it is placed and fed: after consuming the immediate supply of mulberry leaves, it waits patiently for more being provided. I apprehend this cannot be said of any other insect whatever. This docile quality of the worm harmonizes beautifully with its vast importance to mankind, in furnishing a material which affords our most elegant and beautiful, if not most useful, of garments. The same remark applies to the insect in the fly or moth state, the female being quite incapable of flight, and the male, although of a much lighter make, and more active, can fly but very imperfectly; the latter circumstance ensures to us the eggs for the following season, and thus completes the adaptation of the insect, in its different stages, to the useful purpose it is destined to fulfil for our advantage.

The Possibility of introducing and naturalizing that beautiful Insect the Fire Fly.—It abounds not only in Canada, where the winters are so severe, but in the villages of the Vaudois in Piedmont. These are a poor people much attached to the English: and, at 10s. a dozen, would, no doubt, deliver in Paris, in boxes properly contrived, any number of these creatures, in every stage of their existence, and even in the egg, should that be desired: and if twenty dozen were turned out in different parts of England, there cannot remain a doubt but that, in a few years, they would be common through the country; and, in our summer evenings, be exquisitely beautiful.

Vigne, in his Six Months in America, says:—"At Baltimore I first saw the fire-fly. They begin to appear about sunset, after which they are sparkling in all directions. In some places ladies wear them in their hair, and the effect is said to be very brilliant. Mischievous boys will sometimes catch a bull-frog, and fasten them all over him. They show to great advantage; while the poor frog, who cannot understand the 'new lights' that are breaking upon him, affords amusement to his tormentors by hopping about in a state of desperation."

The Vampire Bat.—Bishop Heber's opinion of the innocence of this creature by no means agrees with what one has read of his bloodthirsty habits; and particularly the instances given by Captain Stedman, in his Travels of Surinam, who, more than once, individually, experienced the inconvenience of the Sangrado system of blood-letting, or, more properly, blood-taking, pursued by this practitioner.

"Non missura cutern, nisi plena cruoris hirudo."HOR."This leech will suck the vein, untilFrom your heart's blood he gets his fill."In answer to a query, "whether the vampire of India and that of South America be of one species," Mr. Waterton replies, "I beg to say that I consider them distinct species. I have never yet seen a bat from India with a membrane rising perpendicularly from the end of its nose; nor have I ever been able to learn that bats in India suck animals, though I have questioned many people on this subject. I could only find two species of bats in Guiana, with a membrane rising from the nose. Both these kinds suck animals and eat fruit; while those bats without a membrane on the nose seem to live entirely upon fruit and insects, but chiefly insects. A gentleman, by name Walcott, from Barbadoes, lived high up the river Demerara. While I was passing a day or two at his house, the vampires sucked his son a boy of about ten or eleven years old, some of his fowls and his jack-ass. The youth showed me his forehead at daybreak: the wound was still bleeding apace, and I examined it with minute attention. The poor ass was doomed to be a prey to these sanguinary imps of night: he looked like misery steeped in vinegar. I saw, by the numerous sores on his body, and by his apparent debility, that he would soon sink under his afflictions. Mr. Walcott told me that it was with the greatest difficulty he could keep a few fowls, on account of the smaller vampire; and that the larger kind were killing his poor ass by inches. It was the only quadruped he had brought up with him into the forest.

"Although I was so long in Dutch Guiana and visited the Orinoco and Cayenne, and ranged through part of the interior of Portuguese Guiana, still I could never find out how the vampires actually draw the blood; and, at this day, I am as ignorant of the real process as though I had never been in th« vampire's country. I should not feel so mortified at my total failure in attempting the discovery, had. I not made such diligent search after the vampire, and examined its haunts. Europeans may consider as fabulous the stories related of the vampire; but, for my own part, I must believe in its powers of sucking blood from living animals, as I have repeatedly seen both men and beasts which had been sucked, and, moreover, I have examined very minutely their bleeding wounds.

"Wishful of having it in my power to say that I had been sucked by the vampire, and not caring for the loss of ten or twelve ounces of blood, I frequently and designedly put myself in the way of trial. But the vampire seemed to take a personal dislike to me; and the provoking brute would refuse to give my clavet one solitary trial, though he would tap the more favoured Indian's toe, in a hammock within a few yards of mine. For the space of eleven months, I slept alone in the loft of a woodcutter's abandoned house in the forest; and though the vampire came in and out every night, and I had the finest opportunity of seeing him, as the moon shone through apertures where windows had once been, I never could be certain that I saw him make a positive attempt to quench his thirst from my veins, though he often hovered over the hammock."

THE STORK

Is now rarely seen in Britain; one was killed a short time since in the neighbourhood of Ethie House, and is to be seen in Mr. Mollison's Museum, Bridge-street, Montrose. The editor of the Montrose Review believes that a stork had not been killed in Scotland since the year 1766.

FINE ARTS

THE GRAVE OF TITIAN

Beneath this plain sepulchral stone, in the church of Santa Maria de Frari, at Venice—rest the ashes of TITIAN, the prince of the Venetian school of painters, and who, "was worthy of being waited upon by Cæsar." Yes, this alone denotes his grave at the foot dell'Altare di Crocisfisso.

Titian was born at a sequestered town in the Alps of Friuli, in the year 1477, his father being of the ancient family of Vecelli. He began very early to show a turn for drawing, and designed a figure of the Virgin, with the juice of flowers, the only colours probably within his reach. He was the scholar of Giovanni Bellino, but adopted the manner of Giorgione so successfully, that to several portraits their respective claims could not be ascertained. The Duke of Ferrara was so attached to Titian, that he frequently invited him to accompany him in his barge from Venice to Ferrara. At the latter place he became acquainted with Ariosto. In 1647, at the invitation of Charles V. Titian joined the imperial court. The emperor then advanced in years sat to him for the third time. During the time of sitting, Titian happened to drop one of his pencils, the emperor took it up; and on the artist expressing how unworthy he was of such an honour, Charles replied, "that Titian was worthy of being waited upon by Cæsar." But, "to reckon up the protectors and friends of Titian, would be to name nearly all the persons of the age, to whom rank, talent, and exalted character, appertained. Being full of years and honours, he fell a victim to the plague in 1576, at the age of ninety-nine. To perpetuate his memory, the artists at Venice proposed celebrating his obsequies, with great pomp and magnificence in the church of St. Luke, the programme of which is given at length, by Ridolfi; but, owing to the prevalence of the plague, no funeral ceremony was allowed by the state: the authorities, however, made an exception in Titian's favour, and suffered him to be buried in the church of Friari, as we have stated."

Sir Abraham Hume, the accomplished annotator of the Life and Works of Titian, observes: "It appears to be generally understood that Titian had, in the different periods of life, three distinct manners of painting; the first hard and dry, resembling his master, Giovanni Bellino; the second, acquired from studying the works of Giorgione, was more bold, round, rich in colour, and exquisitely wrought up; the third was the result of his matured taste and judgment, and properly speaking, may be termed his own; in which he introduced more cool tints into the shadows and flesh, approaching nearer to nature than the universal glow of Giorgione." After stating what little is known of the mechanical means employed by Titian in the colouring of his pictures, Sir Abraham observes: "Titian's grand secret of all, appears to have consisted in the unremitting exercise of application, patience, and perseverance, joined to an enthusiastic attachment to his art: his custom was to employ considerable time in finishing his pictures, working on them repeatedly, till he brought them to perfection; and his maxim was, that whatever was done in a hurry, could not be well done." In manners and character, as well as talent, Titian may not inappropriately be associated with "the most eminent painter this country ever produced"—Sir Joshua Reynolds.

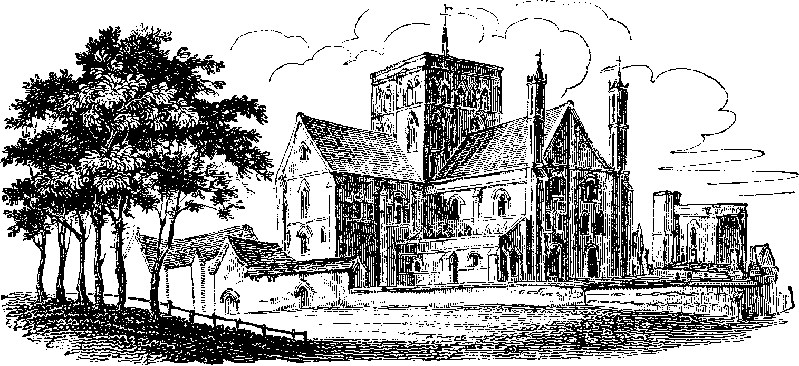

HOSPITAL OF ST. CROSS, HANTS

(The Church.)

This is one of the most interesting structures in Great Britain. It stands about one mile west from Winchester, on the banks of the river Itchin. Its architectural character is of the first importance in illustrating the superior skill of our ancestors; while it has retained more of its original character than any similar record of ancient piety and charity in our island. Dr. Milner, in allusion to its principal features, observes: "the lofty tower, with the grated door, and porter's lodge beneath it; the retired ambulatory; the separate cells; the common refectory; the venerable church; the black flowing dress and the silver cross worn by the members; the conventual appellation of brother, with which they salute each other; in short, the silence, the order, and the neatness, that here reign, seem to recall the idea of a monastery to those who have seen one, and will give no imperfect idea of such an establishment to those who have not had that advantage."3

St. Cross, however, "never was a monastery, but only an hospital for the support of ancient and infirm men, living together in a regular and devout manner." The original founder was Henry de Blois, bishop of Winchester, who instituted it, between the years 1132 and 1136; and required that "thirteen poor men, so decayed and past their strength that without charitable assistance they cannot maintain themselves, shall abide continually in the hospital, who shall be provided with proper clothing and beds suitable to their infirmities; and shall have an allowance daily of good wheat bread, good beer, three messes each for dinner, and one for supper. That beside these thirteen poor, a hundred other poor, of modest behaviour and the most indigent that can be found, shall be received daily at dinner-time, and shall have each a loaf of coarser bread, one mess, and a proper allowance of beer, with leave to carry away with them whatever remains of their meat and drink after dinner." They were to dine in a hall appointed for the purpose, and called Hundred Mennes Hall, from this circumstance. The establishment also contained an endowment for a master, a steward, four chaplains, thirteen clerks, and seven choristers.

But, in those "good old times," abuses in institutions formed for the best and wisest purposes were not uncommon; and in the case of St. Cross, so early did evil begin to counteract good, that, in little more than two centuries from its foundation, the revenues assigned for the annual fulfilment of the founder's wishes, were grossly misapplied. They had increased in value, and the masters and brethren of the hospital of St. John of Jerusalem, who were guardians and administrators, seized the surplus and put it into their own pockets. Bishop Wykeham, who was appointed to the see of Winchester, in 1366, set about the reform of these abuses, which he was enabled to do by his canonical jurisdiction:—"he determined that the whole revenue of the hospital should be dedicated to the poor, as was the intention of the founder, and having in vain tried admonition and remonstrance, summoned the four masters to appear before him and answer for their stewardship. They were bold enough to set Wykeham at defiance, and availed themselves of all the subtleties of the law, and of all manner of evasion, by appeal and otherwise, to thwart and throw him. The upright bishop persisted—he called them to the severest account—had them fined, and till they made restitution, excommunicated—and finally restored the whole endowment to its primitive purpose."4

The propriety and good effects of Wykeham's restoration were so apparent, that his successor, Cardinal Beaufort, having determined to engage in some permanent charity, resolved rather to enlarge this institution, than to found a new one. "He therefore endowed it for the additional support of two priests, and thirty-five poor men, who were to become residents, and three hospital nuns, who were to attend upon the sick brethren: he also caused a considerable portion of the hospital to be rebuilt."5 Of the present establishment we shall presently speak in detail. "The hospital," says Lowth, "though much diminished in its revenues, by what means I cannot say, yet still subsists upon the remains of both endowments."

The buildings of the hospital composed two courts; but the south side of the interior quadrangle has been pulled down. The entrance to the first court from the north is through a capacious gateway.6 On the east side is the Hundred-Mennes Hall, which is about forty feet long, and has been converted into a brewhouse; the roof is of Irish oak, and left open to the timbers, adjoining are the master's apartments. On the west is a range of offices; and, on the south, with portions of other buildings, is the lofty and handsome tower gateway, erected by Cardinal Beaufort, whose statue, in his Cardinal's habit, is represented kneeling in an elegant niche in the upper part: two other niches, of the same form, but deprived of their statues, appear also on the same level. Milner describes the embellishments of this tower: "in a cornice over the gates we behold the Cardinal's hat displayed, together with the busts of his father, John of Gaunt, of his royal nephews, Henry IV. and Henry V., and of his predecessor, Wykeham: in the spandrils, on each side, are the founder's arms. The centre boss in the groining of the gateway is carved into a curious cross, composed of leaves, and surrounded with a crown of thorns: on the left is the door of the porter's lodge.7 Passing through this gateway, the spectator sees, on his right, a long line of buildings, of the age of the original foundation, for the use of the brethren, each of whom has a house and garden to himself. On the left is an ambulatory, or cloister, 135 feet in length, and extending to the church on the south-east. Above the ambulatory is the ancient infirmary, and chambers called the Nuns's rooms, from their having been allotted to three hospital sisters on the foundation of Cardinal Beaufort. The centre of the court has a grass-plot, and gravel walks intersecting parterres of flowers, shrubs, &c."

Dr. Milner observes "the present establishment of St. Cross is but the wreck of its two ancient institutions; it having been severely fleeced, though not quite destroyed, like so many other hospitals at the Reformation. Instead of seventy residents, as well clergy as laity, who were here entirely supported, besides one hundred out-members, who daily received their meat and drink, the charity consists at present but of ten residing brethren and three out-pensioners, exclusive of one chaplain and the master. It is true, however, that certain "doles" of bread continue to be distributed to the poor of the neighbourhood; and what is, perhaps, the only vestige left in the kingdom of the simplicity and hospitality of ancient times, the porter is daily furnished with a certain quantity of good bread and beer, of which every traveller, or other person whosoever, that knocks at the lodge, and calls for relief, is entitled to partake gratuitously."

Such was the state of the charity when Dr. Milner wrote, or, in the year 1809. Our Correspondent, P.Q. has furnished us with the following information to the 20th of last May.

"The funds of this hospital are very ample; for, after providing the master (the present Earl of Guildford)8 with a liberal sinecure, supporting the brethren and servants, and upholding the very extensive buildings, there are distributed the following 'doles:'

"On the 3rd of May, 10th of August, and the eve of the festivals of Easter, Whitsuntide, and Christmas, annually, the whole of the brethren and the steward of the house assemble and form two lines or ranks, at sunset, within the door of the outer gateway; when, to every person (even to infants) who applies at the gate, is given a loaf of brown bread, weighing about three pounds. This distribution is continued until all the bread is given away; and if the applicants should exceed the loaves in number, to each of the remaining persons is given an halfpenny, be they ever so numerous.

"These 'doles' are very beneficial to the poor of Winchester and vicinity; for to all who attend and obtain an early admission a loaf is given. I know, that when I was a boy, and never missed going to the 'doles,' some families, where the children were numerous, received from seven to ten loaves.

"Likewise every traveller who applies at the porter's lodge at the outer gate of this hospital is entitled to, and receives, a horn of good beer and a loaf or slice of bread. This demand is frequently made by persons of a different quality from that intended by the founder, for the sake of attesting the peculiarity of the custom. The quantity of bread given to each person is about four ounces—of beer about three-fourths of a pint."

We next proceed to describe the exterior of the venerable church: the interior will form the subject of a future article.

On entering the second court the first object that usually attracts attention is the Church of St. Cross, which extends a considerable distance into the court, and destroys its regularity on the east side. The exterior of the church is not altogether imposing. "The windows, with one exception, are seen to disadvantage from without, and the whole building is enveloped in a shroud of yellow gravelly plaister, strangely dissonant with ideas of Norman masonry."9 The church is built in the cathedral form, with a nave and transept, and a low and massive tower, rising from the intersection: the whole length of the church is 150 feet; the length of the transept is 120 feet. The architecture of this structure is singularly curious, and deserving the attention of the antiquary, as it appears to throw a light on the progress, if not on the origin, of the pointed or English style. Our Correspondent states the whole to have been repaired about twenty-two years since, at a very considerable expense.

THE PUBLIC JOURNALS

SCRAPS FROM THE DIARY OF A TRAVELLER