Полная версия

Полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 20, No. 562, Saturday, August 18, 1832.

No man is so insignificant as to be sure his example can do no hurt.

—Lord ClarendonTHE PUBLIC JOURNALS

PADDY FOOSHANE'S FRICASSEE

Paddy Fooshane kept a shebeen house at Barleymount Cross, in which he sold whisky—from which his Majesty did not derive any large portion of his revenues—ale, and provisions. One evening a number of friends, returning from a funeral–all neighbours too—stopt at his house, "because they were in grief," to drink a drop. There was Andy Agar, a stout, rattling fellow, the natural son of a gentleman residing near there; Jack Shea, who was afterwards transported for running away with Biddy Lawlor; Tim Cournane, who, by reason of being on his keeping, was privileged to carry a gun; Owen Connor, a march-of-intellect man, who wished to enlighten proctors by making them swallow their processes; and a number of other "good boys." The night began to "rain cats and dogs," and there was no stirring out; so the cards were called for, a roaring fire was made down, and the whisky and ale began to flow. After due observation, and several experiments, a space large enough for the big table, and free from the drop down, was discovered. Here six persons, including Andy, Jack, Tim—with his gun between his legs—and Owen, sat to play for a pig's head, of which the living owner, in the parlour below, testified, by frequent grunts, his displeasure at this unceremonious disposal of his property.

Card-playing is very thirsty, and the boys were anxious to keep out the wet; so that long before the pig's head was decided, a messenger had been dispatched several times to Killarney, a distance of four English miles, for a pint of whisky each time. The ale also went merrily round, until most of the men were quite stupid, their faces swoln, and their eyes red and heavy. The contest at length was decided; but a quarrel about the skill of the respective parties succeeded, and threatened broken heads at one time. At last Jack Shea swore they must have something to eat;–him but he was starved with drink, and he must get some rashers somewhere or other. Every one declared the same; and Paddy was ordered to cook some griskins forthwith. Paddy was completely nonplussed:—all the provisions were gone, and yet his guests were not to be trifled with. He made a hundred excuses—"'Twas late—'twas dry now—and there was nothing in the house; sure they ate and drank enough." But all in vain. The ould sinner was threatened with instant death if he delayed. So Paddy called a council of war in the parlour, consisting of his wife and himself.

"Agrah, Jillen, agrah, what will we do with these? Is there any meat in the tub? Where is the tongue? If it was yours, Jillen, we'd give them enough of it; but I mane the cow's." (aside.)

"Sure the proctors got the tongue ere yesterday, and you know there an't a bit in the tub. Oh the murtherin villains! and I'll engage 'twill be no good for us, after all my white bread and the whisky. That it may pison 'em!"

"Amen! Jillen; but don't curse them. After all, where's the meat? I'm sure that Andy will kill me if we don't make it out any how;—and he hasn't a penny to pay for it. You could drive the mail coach, Jillen, through his breeches pocket without jolting over a ha'penny. Coming, coming; d'ye hear 'em?"

"Oh, they'll murther us. Sure if we had any of the tripe I sent yesterday to the gauger."

"Eh! What's that you say? I declare to God here's Andy getting up. We must do something. Thonom an dhiaoul, I have it. Jillen run and bring me the leather breeches; run woman, alive! Where's the block and the hatchet? Go up and tell 'em you're putting down the pot."

Jillen pacified the uproar in the kitchen by loud promises, and returned to Paddy. The use of the leather breeches passed her comprehension; but Paddy actually took up the leather breeches, tore away the lining with great care, chopped the leather with the hatchet on the block, and put it into the pot as tripes. Considering the situation in which Andy and his friends were, and the appetite of the Irish peasantry for meat in any shape—"a bone" being their summum bonum—the risk was very little. If discovered, however, Paddy's safety was much worse than doubtful, as no people in the world have a greater horror of any unusual food. One of the most deadly modes of revenge they can employ is to give an enemy dog's or cat's flesh; and there have been instances where the persons who have eaten it, on being informed of the fact, have gone mad. But Paddy's habit of practical jokes, from which nothing could wean him, and his anger at their conduct, along with the fear he was in did not allow him to hesitate a moment. Jillen remonstrated in vain. "Hould your tongue, you foolish woman. They're all as blind as the pig there. They'll never find it out. Bad luck to 'em too, my leather breeches! that I gave a pound note and a hog for in Cork. See how nothing else would satisfy 'em!" The meat at length was ready. Paddy drowned it in butter, threw out the potatoes on the table, and served it up smoking hot with the greatest gravity.

"By –," says Jack Shea, "that's fine stuff! How a man would dig a trench after that."

"I'll take a priest's oath," answered Tim Cohill, the most irritable of men, but whose temper was something softened by the rich steam;—

"Yet, Tim, what's a priest's oath? I never heard that."

"Why, sure, every one knows you didn't ever hear of anything of good."

"I say you lie, Tim, you rascal."

Tim was on his legs in a few moments, and a general battle was about to begin; but the appetite was too strong, and the quarrel was settled; Tim having been appeased by being allowed to explain a priest's oath. According to him, a priest's oath was this:—He was surrounded by books, which were gradually piled up until they reached his lips. He then kissed the uppermost, and swore by all to the bottom. As soon as the admiration excited by his explanation, in those who were capable of hearing Tim, had ceased, all fell to work; and certainly, if the tripes had been of ordinary texture, drunk as was the party, they would soon have disappeared. After gnawing at them for some time, "Well," says Owen Connor, "that I mightn't!—but these are the quarest tripes I ever eat. It must be she was very ould."

"By –," says Andy, taking a piece from his mouth to which he had been paying his addresses for the last half hour, "I'd as soon be eating leather. She was a bull, man; I can't find the soft end at all of it."

"And that's true for you, Andy," said the man of the gun; "and 'tis the greatest shame they hadn't a bull-bait to make him tinder. Paddy, was it from Jack Clifford's bull you got 'em? They'd do for wadding, they're so tough."

"I'll tell you, Tim, where I got them—'twas out of Lord Shannon's great cow at Cork, the great fat cow that the Lord Mayor bought for the Lord Lieutenant—Asda churp naur hagushch."14

"Amen, I pray God! Paddy. Out of Lord Shandon's cow? near the steeple, I suppose; the great cow that couldn't walk with tallow. By –, these are fine tripes. They'll make a man very strong. Andy, give me two or three libbhers more of 'em."

"Well, see that! out of Lord Shandon's cow: I wonder what they gave her, Paddy. That I mightn't!—but these would eat a pit of potatoes. Any how, they're good for the teeth. Paddy, what's the reason they send all the good mate from Cork to the Blacks?"

But before Paddy could answer this question, Andy, who had been endeavouring to help Tim, uttered a loud "Thonom an dhiaoul! what's this? Isn't this flannel?" The fact was, he had found a piece of the lining, which Paddy, in his hurry, had not removed; and all was confusion. Every eye was turned to Paddy; but with wonderful quickness he said "'Tis the book tripe, agragal, don't you see?"—and actually persuaded them to it.

"Well, any how," says Tim, "it had the taste of wool."

"May this choke me," says Jack Shea, "if I didn't think that 'twas a piece of a leather breeches when I saw Andy chawing it."

This was a shot between wind and water to Paddy. His self-possession was nearly altogether lost, and he could do no more than turn it off by a faint laugh. But it jarred most unpleasantly on Andy's nerves. After looking at Paddy for some time with a very ominous look, he said, "Yirroo Pandhrig of the tricks, if I thought you were going on with any work here, my soul and my guts to the devil if I would not cut you into garters. By the vestment I'd make a furhurmeen of you."

"Is it I, Andy? That the hands may fall off me!"

But Tim Cohill made a most seasonable diversion. "Andy, when you die, you'll be the death of one fool, any how. What do you know that wasn't ever in Cork itself about tripes. I never ate such mate in my life; and 'twould be good for every poor man in the County of Kerry if he had a tub of it."

Tim's tone of authority, and the character he had got for learning, silenced every doubt, and all laid siege to the tripes again. But after some time, Andy was observed gazing with the most astonished curiosity into the plate before him. His eyes were rivetted on something; at last he touched it with his knife, arid exclaimed, "Kirhappa, dar dhia!"—[A button by G—.]

"What's that you say?" burst from all! and every one rose in the best manner he could, to learn the meaning of the button.

"Oh, the villain of the world!" roared Andy, "I'm pisoned! Where's the pike? For God's sake Jack, run for the priest, or I'm a dead man with the breeches. Where is he?—yeer bloods won't ye catch him, and I pisoned?"

The fact was, Andy had met one of the knee-buttons sewed into a piece of the tripe, and it was impossible for him to fail discovering the cheat. The rage, however, was not confined to Andy. As soon as it was understood what had been done, there was an universal rush for Paddy and Jillen; but Paddy was much too cunning to be caught, after the narrow escape he had of it before. The moment after the discovery of the lining, that he could do so without suspicion, he stole from the table, left the house, and hid himself. Jillen did the same; and nothing remained for the eaters, to vent their rage, but breaking every thing in the cabin; which was done in the utmost fury. Andy, however, continued watching for Paddy with a gun, a whole month after. He might be seen prowling along the ditches near the shebeen-house, waiting for a shot at him. Not that he would have scrupled to enter it, were he likely to find Paddy there; but the latter was completely on the shuchraun, and never visited his cabin except by stealth. It was in one of those visits that Andy hoped to catch him.

—Tait's Edinburgh MagazineCONVERSATIONS WITH LORD BYRON

By the Countess of BlessingtonOne of our first rides with Lord Byron was to Nervi, a village on the sea-coast, most romantically situated, and each turn of the road presenting various and beautiful prospects. They were all familiar to him, and he failed not to point them out, but in very sober terms, never allowing any thing like enthusiasm in his expressions, though many of the views might have excited it.

His appearance on horseback was not advantageous, and he seemed aware of it, for he made many excuses for his dress and equestrian appointments. His horse was literally covered with various trappings, in the way of cavesons, martingales, and Heaven knows how many other (to me) unknown inventions. The saddle was à la Hussarde with holsters, in which he always carried pistols. His dress consisted of a nankeen jacket and trousers, which appeared to have shrunk from washing; the jacket embroidered in the same colour, and with three rows of buttons; the waist very short, the back very narrow, and the sleeves set in as they used to be ten or fifteen years before; a black stock, very narrow; a dark-blue velvet cap with a shade, and a very rich gold band and large gold tassel at the crown; nankeen gaiters, and a pair of blue spectacles, completed his costume, which was any thing but becoming. This was his general dress of a morning for riding, but I have seen it changed for a green tartan plaid jacket. He did not ride well, which surprised us, as, from the frequent allusions to horsemanship in his works, we expected to find him almost a Nimrod, It was evident that he had pretensions on this point, though he certainly was what I should call a timid rider. When his horse made a false step, which was not unfrequent, he seemed discomposed; and when we came to any bad part of the road, he immediately checked his course and walked his horse very slowly, though there really was nothing to make even a lady nervous. Finding that I could perfectly manage (or what he called bully) a very highly-dressed horse that I daily rode, he became extremely anxious to buy it; asked me a thousand questions as to how I had acquired such a perfect command of it, &c. &c. and entreated, as the greatest favour, that I would resign it to him as a charger to take to Greece, declaring he never would part with it, &c. As I was by no means a bold rider, we were rather amused at observing Lord Byron's opinion of my courage; and as he seemed so anxious for the horse, I agreed to let him have it when he was to embark. From this time he paid particular attention to the movements of poor Mameluke (the name of the horse), and said he should now feel confidence in action with so steady a charger.

April—. Lord Byron dined with us today. During dinner he was as usual gay, spoke in terms of the warmest commendation of Sir Walter Scott, not only as an author, but as a man, and dwelt with apparent delight on his novels, declaring that he had read and re-read them over and over again, and always with increased pleasure. He said that he quite equalled, nay, in his opinion, surpassed Cervantes. In talking of Sir Walter's private character, goodness of heart, &c., Lord Byron became more animated than I had ever seen him; his colour changed from its general pallid tint to a more lively hue, and his eyes became humid: never had he appeared to such advantage, and it might easily be seen that every expression he uttered proceeded from his heart. Poor Byron!—for poor he is even with all his genius, rank, and wealth—had he lived more with men like Scott, whose openness of character and steady principle had convinced him that they were in earnest in their goodness, and not making believe, (as he always suspects good people to be,) his life might be different and happier! Byron is so acute an observer that nothing escapes him; all the shades of selfishness and vanity are exposed to his searching glance, and the misfortune is, (and a serious one it is to him,) that when he finds these, and alas! they are to be found on every side, they disgust and prevent his giving credit to the many good qualities that often accompany them. He declares he can sooner pardon crimes, because they proceed from the passions, than these minor vices, that spring from egotism and self-conceit. We had a long argument this evening on the subject, which ended, like most arguments, by leaving both of the same opinion as when it commenced. I endeavoured to prove that crimes were not only injurious to the perpetrators, but often ruinous to the innocent, and productive of misery to friends and relations, whereas selfishness and vanity carried with them their own punishment, the first depriving the person of all sympathy, and the second exposing him to ridicule which to the vain is a heavy punishment, but that their effects were not destructive to society as are crimes.

He laughed when I told him that having heard him so often declaim against vanity, and detect it so often in his friends, I began to suspect he knew the malady by having had it himself, and that I had observed through life, that those persons who had the most vanity were the most severe against that failing in their friends. He wished to impress upon me that he was not vain, and gave various proofs to establish this; but I produced against him his boasts of swimming, his evident desire of being considered more un homme de societe than a poet, and other little examples, when he laughingly pleaded guilty, and promised to be more merciful towards his friends.

Byron attempted to be gay, but the effort was not successful, and he wished us good night with a trepidation of manner that marked his feelings. And this is the man that I have heard considered unfeeling! How often are our best qualities turned against us, and made the instruments for wounding us in the most vulnerable part, until, ashamed of betraying our susceptibility, we affect an insensibility we are far from possessing, and, while we deceive others, nourish in secret the feelings that prey only on our own hearts!

—New Monthly MagazineTHE GATHERER

Canary Birds.—In Germany and the Tyrol, from whence the rest of Europe is principally supplied with Canary birds, the apparatus for breeding Canaries is both large and expensive. A capacious building is erected for them, with a square space at each end, and holes communicating with these spaces. In these outlets are planted such trees as the birds prefer. The bottom is strewed with sand, on which are cast rapeseed, chickweed, and such other food as they like. Throughout the inner compartment, which is kept dark, are placed bowers for the birds to build in, care being taken that the breeding birds are guarded from the intrusion of the rest. Four Tyrolese usually take over to England about sixteen hundred of these birds; and though they carry them on their backs nearly a thousand miles, and pay twenty pounds for them originally, they can sell them at 5s. each.

Braithwaite's Steam Fire Engine—will deliver about 9,000 gallons of water per hour to an elevation of 90 feet. The time of getting the machine into action, from the moment of igniting the fuel, (the water being cold,) is 18 minutes. As soon as an alarm is given, the fire is kindled, and the bellows, attached to the engine, are worked by hand. By the time the horses are harnessed in, the fuel is thoroughly ignited, and the bellows are then worked by the motion of the wheels of the engine. By the time of arriving at the fire, preparing the hoses, &c. the steam is ready.

Fisher, bishop of Rochester, was accustomed to style his church his wife, declaring that he would never exchange her for one that was richer. He was a zealous adherent of Pope Paul III. who created him a cardinal. The king, Henry VIII., on learning that Fisher would not refuse the dignity, exclaimed, in a passion, "Yea! is he so lusty? Well, let the pope send him a hat when he will. Mother of God! he shall wear it on his shoulders, for I will leave him never a head to set it on."

Flax is not uncommon in the greenhouses about Philadelphia, but we have not heard of any experiments with it in the open air.—Encyclopaedia Americana.

The Schoolmaster wanted in the East.—Mr. Madden, in his travels in Turkey, Egypt, Nubia, and Palestine, says:—"In all my travels, I could only meet one woman who could read and write, and that was in Damietta; she was a Levantine Christian, and her peculiar talent was looked upon as something superhuman."

La Fontaine had but one son, whom, at the age of 14, he placed in the hands of Harlay, archbishop of Paris, who promised to provide for him. After a long absence, La Fontaine met this youth at the house of a friend, and being pleased with his conversation, was told that it was his own son. "Ah," said he, "I am very glad of it."

Universal Genius.—Rivernois thus describes the character of Fontenelle: "When Fontenelle appeared on the field, all the prizes were already distributed, all the palms already gathered: the prize of universality alone remained, Fontenelle determined to attempt it, and he was successful. He is not only a metaphysician with Malebranche, a natural philosopher with Newton, a legislator with Peter the Great, a statesman with D'Argenson; he is everything with everybody."

Forest Schools.—There are a number of forest academies in Germany, particularly in the small states of central Germany, in the Hartz, Thuringia, &c. The principal branches taught in them are the following:—forest botany, mineralogy, zoology, chemistry; by which the learner is taught the natural history of forests, and the mutual relations, &c. of the different kingdoms of nature. He is also instructed in the care and chase of game, and in the surveying and cultivation of forests, so as to understand the mode of raising all kinds of wood, and supplying a new growth as fast as the old is taken away. The pupil is too instructed in the administration of the forest taxes and police, and all that relates to forests considered as a branch of revenue.

The Weather.—Meteorological journals are now given in most magazines. The first statement of this kind was communicated by Dr. Fothergill to the Gentleman's Magazine, and consisted of a monthly account of the weather and diseases of London. The latter information is now monopolized by the parish-clerks.

Goethe.—The wife of a Silesian peasant, being obliged to go to Saxony, and hearing that she had travelled (on foot) more than half the distance to Goethe's residence, whose works she had read with the liveliest interest, continued her journey to Weimar for the sake of seeing him. Goethe declared that the true character of his works had never been better understood than by this woman. He gave her his portrait.

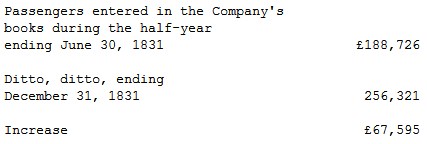

Liverpool and Manchester Railway.—The Company has reported the following result:

Being upwards of 33 per cent. increase of the first six months of the year, and upwards of 135 per cent. increase on the travellers between the two towns during the corresponding months, previously to opening the railway.—Gordon, on Steam Carriages.

Caliga.—This was the name of the Roman soldier's shoe, made in the sandal fashion. The sole was of wood, and stuck full of nails. Caius Caesar Caligula, the fourth Roman Emperor, the son of Germanicus and Agrippina, derived his surname from "Caliga," as having been born in the army, and afterwards bred up in the habit of a common soldier; he wore this military shoe in conformity to those of the common soldiers, with a view of engaging their affections. The caliga was the badge, or symbol of a soldier; whence to take away the caliga and belt, imported a dismissal or cashiering. P.T.W.

The Damary Oak-tree.—At Blandford Forum, Dorsetshire, stood the famous Damary Oak, which was rooted up for firing in 1755. It measured 75 feet high, and the branches extended 72 feet; the trunk at the bottom was 68 feet in circumference, and 23 feet in diameter. It had a cavity in its trunk 15 feet wide. Ale was sold in it till after the Restoration; and when the town was burnt down in 1731, it served as an abode for one family.—Family Topographer, vol. ii.

Brent Tor Church, Devonshire, situate upon a rock.—On Brent Tor is a church, in which is appositely inscribed from Scripture, "Upon this rock will I build my church, and the gates of hell shall not prevail against it." It is said that the parishioners make weekly atonement for their sins, for they cannot go to the church without the previous penance of climbing the steep; and the pastor is frequently obliged to humble himself upon his hands and knees before he can reach the house of prayer. Tradition says it was erected by a merchant to commemorate his escape from shipwreck on the coast, in consequence of this Tor serving as a guide to the pilot. There is not sufficient earth to bury the dead. At the foot of the Tor resided, in 1809, Sarah Williams, aged 109 years. She never lived further out of the parish of Brent Tor, than the adjoining one: she had had twelve children, and a few years before her death cut five new teeth.—Ibid.

The Dairyman's Daughter.—In Arreton churchyard, Isle of Wight, is a tombstone, erected in 1822, by subscription, to mark the grave of Elizabeth Wallbridge, the humble individual whose story of piety and virtue, written by the Rev. Leigh Richmond, under the title of the "Dairyman's Daughter," has attained an almost unexampled circulation. Her cottage at Branston, about a mile distant, is much visited.—Ibid.