Полная версия

Полная версияПолная версия:

The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 20, No. 559, July 28, 1832

*** So, Touchstone's philosophy hath legal warrant: "Is the single man blessed? No: as a walled town is more worthier than a village, so is the forehead of a married man more honourable than the bare brow of a bachelor."—As you like it. (Ed. M.)

SAXON ALMANACS

The Saxons were accustomed to engrave upon square pieces of wood, the courses of the moons for the whole year, (or for a specified space of time) by which they could tell when the new-moons, full-moons, and changes would occur, and these pieces of wood were by them called Al-mon-aght (i.e.) Al-moon-heed, which signifies the regard and observation of all the moons, and from this term is derived the word Almanac.

Many of our readers are probably aware of, or have seen, a Saxon Almanac, answering the above description, in St. John's College, Cambridge. E.J.H.

SPIRIT OF DISCOVERY

EXEMPLARS ABRIDGED FROM MR. BABBAGE'S "ECONOMY OF MACHINERY AND MANUFACTURES."

Voyage of Manufacture.—The produce of our factories has preceded even our most enterprising travellers. Captain Clapperton saw at the court of the Sultan Bello, pewter dishes with the London stamp, and had at the royal table a piece of meat served up on a white wash-hand basin of English manufacture. The cotton of India is conveyed by British ships round half our planet, to be woven by British skill in the factories of Lancashire; it is again set in motion by British capital, and transported to the very plains whereon it grew, is repurchased by the lords of the soil which gave it birth, at a cheaper price than that at which their coarser machinery enables them to manufacture it themselves. At Calicut, in the East Indies (whence the cotton cloth called calico derives its name) the price of labour is one-seventh of that in England, yet the market is supplied from British looms.

Additions to human power.—The force necessary to move a stone along the roughly-chiselled floor of its quarry is nearly two-thirds of its weight; to move it along a wooden floor, three-fifths; by wood upon wood, five-ninths; if the wooden surfaces are soaped, one-sixth; if rollers are used on the floor of the quarry, it requires one-thirty-second part of the weight; if they roll on wood, one-fortieth; and if they roll between wood, one-fiftieth of its weight. At each increase of knowledge, as well as on the contrivance of every new tool, human labour becomes abridged.

Economy of time.—Several pounds of gunpowder may be purchased for a sum acquired by a few days' labour; yet, when this is employed in blasting rocks, effects are produced which could not, even with the best tools, be accomplished by other means in less than many months.

Economy of Materials.—The worn-out saucepans and tin-ware of our kitchens, when beyond the reach of the tinker's art, are not utterly worthless. We sometimes meet carts loaded with old tin kettles and worn-out iron coal-scuttles traversing our streets. These have not yet completed their useful course; the less corroded parts are cut into strips, punched with small holes, and varnished with a coarse black varnish for the use of the trunkmaker, who protects the edges and angles of his box with them; the remainder are conveyed to the manufacturing chemists in the outskirts of the town, who employ them, in conjunction with pyroligneous acid, in making a black dye for the use of calico printers.

Accumulation of Power arises from lifting a weight and then allowing it to fall. A man, even with a heavy hammer, might strike repeated blows upon the head of a pile without producing any effect. But if he raises a much heavier hammer to a much greater height, its fall, though far less frequently repeated, will produce the desired effect.

Regulating Power.—A contrivance for regulating the effect of machinery consists in a vane or a fly, of little weight, but presenting a large surface. This revolves rapidly, and soon acquires an uniform rate, which it cannot greatly exceed, because any addition to its velocity produces a much greater addition to the resistance it meets with from the air. The interval between the strokes on the bell of a clock is regulated by this means; and the fly is so contrived, that this interval may be altered by presenting the arms of it more or less obliquely to the direction in which they move. This kind of fly or vane is generally used in the smaller kinds of mechanism, and, unlike the heavy fly, it is a destroyer instead of a preserver of force. It is the regulator used in musical boxes, and in almost all mechanical toys.

Increase and Diminution of Velocity.—Twisting the fibres of wool by the fingers would be a most tedious operation; in the common spinning-wheel the velocity of the foot is moderate; but, by a very simple contrivance, that of the thread is most rapid. A piece of cat-gut passing round a large wheel, and then round a small spindle, effects this change. The small balls of sewing cotton, so cheap and so beautifully wound, are formed by a machine on the same principle, and but a few steps more complicated. The common smoke-jack is an instrument in which the velocity communicated is too great for the purpose required, and it is transmitted through wheels which reduce it to a more moderate rate.

Extending the Time of Action in Forces.—The half-minute which we daily devote to the winding up of our watches is an exertion of labour almost insensible; yet, by the aid of a few wheels its effect is spread over the whole twenty-four hours. Another familiar illustration may be noticed in our domestic furniture: the common jack by which our meat is roasted, is a contrivance to enable the cook in a few minutes to exert a force which the machine retails out during the succeeding hour in turning the loaded spit.

Saving Time in natural Operations.—The process of tanning formerly occupied from six months to two years; this time being apparently required in order to allow the tanning matter to penetrate into the interior of a thick hide. The improved process consists in placing the hides with the solution of tan in close vessels, and then exhausting the air. The consequence of this is to withdraw any air which might be contained in the pores of the hides, and to employ the pressure of the atmosphere to aid capillary attraction in forcing the tan into the interior of the skins. The effect of the additional force thus brought into action can be equal only to one atmosphere, but a further improvement has been made: the vessel containing the hides is, after exhaustion, filled up with a solution of tan; a small additional quantity is then injected with a forcing-pump. By these means any degree of pressure may be given which the containing vessel is capable of supporting, and it has been found that, by employing such a method, the thickest hides may be tanned in six weeks or two months.

Printing from Wooden Blocks.—A block of box-wood is, in this instance, the substance out of which the pattern is formed: the design being sketched upon it, the workman cuts away with sharp tools every part except the lines to be represented in the impression. This is exactly the reverse of the process of engraving on copper, in which every line to be represented is cut away. The ink, instead of filling the cavities cut in the wood, is spread upon the surface which remains, and is thence transferred to the paper.

Making and Manufacturing.—There exists a considerable difference between the terms making and manufacturing. The former refers to the production of a small, the latter to that of a very large number of individuals; and the difference is well illustrated in the evidence given before the Committee of the House of Commons on the Export of Tools and Machinery. On that occasion Mr. Maudslay stated, that he had been applied to by the Navy Board to make iron tanks for ships, and that he was rather unwilling to do so, as he considered it to be out of his line of business; however, he undertook to make one as a trial. The holes for the rivets were punched by hand-punching with presses, and the 1,680 holes which each tank required cost seven shillings. The Navy Board who required a large number, proposed that he should supply forty tanks a week for many months. The magnitude of the order made it worth while to commence manufacturer, and to make tools for the express business. Mr. Maudslay therefore offered, if the Board would give him an order for two thousand tanks, to supply them at the rate of eighty per week. The order was given: he made the tools, by which the expense of punching the rivet-holes of each tank was reduced from seven shillings to ninepence; he supplied ninety-eight tanks a week for six months, and the price charged for each was reduced from seventeen pounds to fifteen.

Brass-plate Coal Merchants.—In the recent examination by the committee of the House of Commons into the state of the Coal Trade, it appears that five-sixths of the London public is supplied by a class of middle-men who are called in the trade "Brass-plate Coal Merchants:" these consist principally of merchants' clerks, gentlemen's servants, and others, who have no wharfs, but merely give their orders to some true coal-merchant, who sends in the coals from his wharf. The brass-plate coal merchant, of course, receives a commission for his agency, which is just so much loss to the consumer.

Raw Materials.—Gold-leaf consists of a portion of the metal beaten out to so great a degree of thinness, as to allow a greenish-blue light to be transmitted through its pores. About 400 square inches of this are sold, in the form of a small book, containing twenty-five leaves of gold for 1s. 6d. In this case, the raw material, or gold, is worth rather less than two-thirds of the manufactured article. In the case of silver leaf, the labour considerably exceeds the value of the material. A book of fifty leaves, covering above 1,000 square inches is sold for 1s. 3d.

The quantity of labour applied to Venetian gold chains is very great, but incomparably less than that which is applied to some of the manufactures of iron. In the case of the smallest Venetian chain the value of the labour is not above thirty times that of the gold. The pendulum spring of a watch, which governs the vibrations of the balance, costs at the retail price twopence, and weighs fifteen one-hundredths of a grain, whilst the retail price of a pound of the best iron, the raw material out of which fifty thousand such springs are made, is exactly the sum of twopence.

In France bar-iron, made as it usually is with charcoal, costs three times the price of the cast-iron out of which it is made; whilst in England, where it is usually made with coke, the cost is only twice the price of cast-iron.

THE NATURALIST

THE NINE-BANDED ARMADILLO

THE NINE-BANDED ARMADILLO.

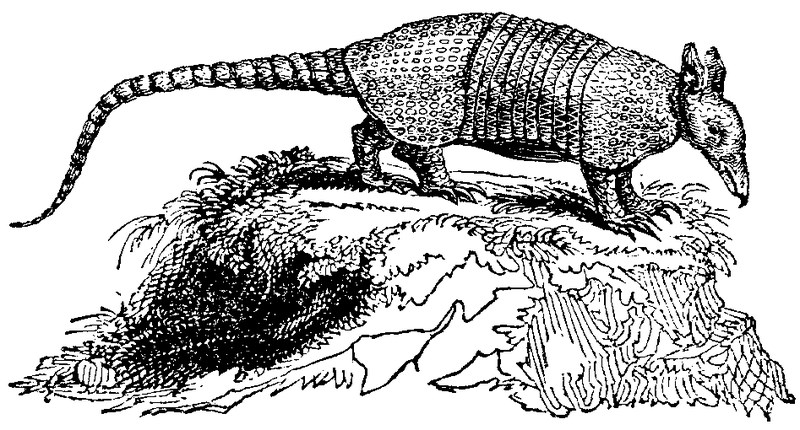

Armadillos are almost exclusively natives of South America, principally of the province of Paraguay. Some inhabit the forests; others are found in the open country. There are several species, all of which are invested with a coat of mail, or a kind of plate armour resembling the covering of the pangolin, or scaly ant-eater, and the shell of the tortoise. This crust or shell covers the upper parts of the animal, and consists of four or five different parts or divisions. The head may be said to have a helmet, and the shoulders a buckler, composed of several transverse series of plates. Transverse bands, varying in the different species from three to twelve, which are movable, cover the body; the crupper has its buckler similar to that on the shoulders, and the tail is protected by numerous rings. The hairs of the body are few, springing from between the plates; the under parts, which are without armour, have rather more hairs. In a living state, the whole armour is capable of yielding considerably to the motions of the body; the pieces or plates being connected by a membrane, like the joints in a tail of a lobster. The under parts present a light grainy skin. The legs are thick and strong, but only long enough to raise the body from the ground; the nails are very powerful, and calculated for digging; and, according to Buffon, the mole is not more expert in burrowing the earth.

Some of the species have nocturnal habits and are very timid, flying to their burrows the moment they hear a noise. Other species quit their retreat equally by day and night, and these are said not to be so rapid in their motions as the others. All the species walk quickly, but they can neither leap, run, nor climb; so that, when pursued, they can only escape by hiding themselves in their holes; if these be too far off, the poor hunted creatures dig a hole before they are overtaken, and with their strong snout and fore claws in a few moments conceal themselves. Sometimes, however, before they are quite concealed, they are caught by the tail, when they struggle so powerfully that the tail often breaks short, and is left in the hands of the pursuers. To prevent this the hunter tickles the animal with a stick, till it looses its hold, and allows itself to be taken without further resistance. At other times, when pursued, and finding flight ineffectual, the Armadillos withdraw the head under the edge of the buckler of the shoulders; their legs, except the feet, are naturally hidden by the borders of the bucklers and the bands; they then contract the body as far towards the shape of a ball as the stretching of the membrane which unites the different movable pieces of the armour will permit.8 Thus defended, they frequently escape danger; but if near a precipice, the animal will sometimes roll itself over, and in this case, says Molina, in his Natural History of Chili, it generally falls to the bottom unhurt.

Armadillos were formerly thought to feed exclusively on vegetables; but they have since been found to devour insects and flesh. The directions of their burrows evince that they search after ant heaps, and the insects quickly disappear from near the hole of an Armadillo. The largest species, the great black Armadillo, common in the forests of Paraguay, feeds on the carcasses of animals; and the graves of the dead which are necessarily formed at a distance from the usual places of sepulture, in countries where the great Armadillo is found, are protected by strong double boards to prevent the animal from penetrating and devouring the body. It appears, also, that it eats young birds, eggs, snakes, lizards, &c. The Indians are very fond of the flesh of the Armadillo as food, especially when young; but, when old, it acquires a strong musky flavour. Mr. Waterton, who tasted the flesh, considered it strong and rank. The shells or crusts are applied to various useful purposes, and painted of different colours are made into boxes, baskets, &c.

Cuvier remarks that that old mode of distinguishing the species of Armadillos by the number of the bands is clearly objectionable, inasmuch as D'Azara has established that not only the number of these bands varies, in the different individuals of the same species, but further, that there are individuals of different species which have the same number of bands. Eight species mentioned by D'Azara are admitted as distinct, but the whole number is very doubtful.

(The species represented in the Cut,9 or, the Nine-banded, is the most common. In the Zoological Gardens, in the Regent's Park, and in Surrey, are several specimens. They are usually kept in cages, but on fine sunny days are let out upon the turf. Their general pace may here be seen to advantage: it is a sort of quick shuffling walk, and they get over the ground easily, notwithstanding the weight of their shelly covering.)

In conclusion, it is interesting to remark that the whole series of these very singular animals offers a notable example of one genus being confined to a particular country. We have observed that they all belong to South America; nor do we find that in any parts of the old world, or, indeed, in the great northern division of the new, any races of quadrupeds at all to resemble them, or in any manner to be compared with them. They may be said to stand perfectly insulated; they exhibit all the characters of a creation entirely distinct, and except as to the general characters of mammiferous quadrupeds, perfectly of their own kind. There is no break in the whole circle of them, no deviation or leaning towards any other organized form; so that the boldest conjecture will hardly venture to guess at any other than a separate creation for these animals, and a distinct allocation in South America. This peculiarity is rendered the more striking by the facility with which it seems to endure removal, even to our latitudes; thereby proving that its present confined identity with South America is not altogether the result of its physical necessities.10

CLIMATE OF CANADA

From Sketches, by a BackwoodsmanIt never has been accountable to me, how the heat of the sun is regulated. There is no part of Upper Canada that is not to the south of Penzance, yet there is no part of England where the cold is so intense as in Canada; nay, there is no cold in England equal to the cold of Virginia, which, were it on the European side of the hemisphere, would be looked upon as an almost tropical climate. To explain to an European what the climate of Upper Canada is, we would say, that in summer it is the climate of Italy, in winter that of Holland; but in either case we should only be giving an illustration, for in both winter and summer it possesses peculiarities which neither of these two climates possess. The summer heat of Upper Canada generally ranges towards 80° Fahrenheit; but should the wind blow twenty-four hours steadily from the north, it will fall to 40° during the night. The reason of this seems to be the enormous quantity of forest over which that wind blows, and the leaves of the trees affording such an extensive surface of evaporation. One remarkable peculiarity in the climate of Canada, when compared with those to which we have likened it, is its dryness. Far from the ocean, the salt particles that somehow or other exist in the atmosphere of sea-bounded countries are not to be found here; roofs of tinned iron of fifty years' standing are as bright as the day they came out of the shop; and you may leave a charge of powder in your gun for a month, and find, at the end of it, that it goes off without hanging fire. The diseases of the body, too, that are produced by a damp atmosphere, are uncommon here. It may be a matter of surprise to some to hear, that pectoral and catarrhal complaints, which, from an association of ideas they may connect with cold, are here hardly known. In the cathedral at Montreal, where from three to five thousand people assemble every Sunday, you will seldom find the service interrupted by a cough, even in the dead of winter and in hard frost; whereas, in Britain, from the days of Shakspeare, even in a small country church, "coughing drowns the parson's saw." Pulmonary consumption, too, the scourge alike of England and the sea-coast of America, is so rare in the northern parts of New York and Pennsylvania, and the whole of Upper Canada, that in eight years' residence I have not seen as many cases of the disease as I have in a day's visit to a provincial infirmary at home. The only disease we are annoyed with here, that we are not accustomed to at home, is the intermittent fever,—and that, though most abominably annoying, is not by any means dangerous: indeed, one of the most annoying circumstances connected with it is, that, instead of being sympathized with, you are only laughed at. Otherwise the climate is infinitely more healthy than that of England. Indeed, it may be pronounced the most healthy country under the sun, considering that whisky can be procured for about one shilling sterling per gallon. Though the cold of a Canadian winter is great, it is neither distressing nor disagreeable. There is no day during winter, except a rainy one, in which a man need be kept from his work. It is a fact, though as startling as some of the dogmas of the Edinburgh school of political economy, that the thermometer is no judge of warm or cold weather. Thus, with us in Canada, when it is low, (say at zero,) there is not a breath of hair, and you can judge of the cold of the morning by the smoke rising from the chimney of a cottage, and shooting up straight like the steeple of a church, then gradually melting away in the beautiful clear blue of the morning sky: yet in such weather it is impossible to go through a day's march in your great coat; whereas, at home, when the wind blows from the north-east, though the thermometer stands at from 55° to 60° you find a fire far from oppressive. The fact is, that a Canadian winter is by far the pleasantest season of the year, for everybody is idle, and everybody is determined to enjoy himself. Between the summer and winter of Canada, a season exists, called the Indian summer. During this period, the atmosphere has a smoky, hazy effect, which is ascribed by the people generally to the simultaneous burning of the prairies of the western part of the continent. This explanation I take to be absurd; since, if it were so to be accounted for, the wind must necessarily blow from that quarter, which is not in all instances the case. During this period, which generally occupies two or three weeks of the month of November, the days are pleasant, and with abundance of sunshine, and the nights present a cold, clear, black frost. When this disappears, the rains commence, which always precede winter; for it is a proverb in the Lower Province, among the French Canadians, that the ditches never freeze till they are full. Then comes the regular winter, which, if rains and thaws do not interfere, is very pleasant; and that is broken up by rains again, which last until the strong sun of the middle of May renders everything dry and in good order. A satirical friend of mine gave a caricature account of the climate of the province, when he said that, for two months of the spring and two months of the autumn, you are up to your middle in mud; for four months of summer you are broiled by the heat, choked by the dust, and devoured by the mosquitoes; and for the remaining four months, if you get your nose above the snow, it is to have it bit off by the frost.

THE PUBLIC JOURNALS

AN INCIDENT IN THE LIFE OF A RASCAL

"His name is never heard."

Late one evening, a packet of letters, just arrived by the English mail, was handed to Mynheer Von Kapell, a merchant of Hamburgh. His head clerk awaited, as usual, for any orders which might arise from their contents; and was not a little surprised to observe the brow of his wealthy employer suddenly clouded; again and again he perused the letter he held, at last audibly giving vent to his feelings—

"Donder and blitzen!" he burst forth, "but this is a shock, who would have thought it? The house of Bennett and Ford to be shaken thus! What is to be done?"

"Bennett and Ford failed!"' cried the astonished clerk.

"Failed! ten thousand devils! not so bad as that; but they are in deep distress, and have suffered a heavy loss; but read, good Yansen! and let me have your advice."

The clerk read as follows:—

"London, August 21st.

"Most respected friend,

"Yours of the 5th inst. came safe to hand, and will meet prompt attention. We have to inform you, with deep regret, that the son of the trustworthy cashier of this long-established house has absconded, taking with him bills accepted by our firm, to a large amount, as per margin; and a considerable sum in cash. We have been able to trace the misguided young man to a ship bound for Holland, and we think it probable he may visit Hamburgh, (where our name is so well known and, we trust, so highly respected) for the purpose of converting these bills into cash. He is a tall, handsome youth, about five feet eleven inches, with dark hair and eyes; speaks French and German well, and was dressed in deep mourning, in consequence of the recent death of his mother. If you should be able to find him, we have to request you will use your utmost endeavours to regain possession of the bills named in the margin; but, as we have a high respect for the father of the unfortunate young man, we will further thank you to procure for him a passage on board the first vessel sailing for Batavia, paying the expense of his voyage, and giving him the sum of two hundred louis d'or, which you will place to our account current, on condition that he does not attempt to revisit England till he receives permission so to do.