Полная версия

Полная версияПолная версия:

The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 19, No. 554, June 30, 1832

Rogers came in late, and went away early, looking sallower and more indifferent than usual. He paid a few bows and compliments to two or three noble peeresses, and then retired.

The Rev. Thomas Frognel Dibdin was there. He was very facetious and quaint: when he found himself by my side, he instantly started off, crying to me; "Brobdignagian; We Lilliputians must not stand by you! You would make a soldier for the King of Prussia! Look at that tall lady there, that Miss de V–; why do you not take her for a wife?" E– G–n heard what he said, and looked fierce at us both! I expected another Bluviad! Perhaps the ingenious bibliographer does not recollect the conversation; but he may be assured it took place. And I entreat also Anna Maria Porter to tax her memory, and recall the very interesting and sensible conversation I had with her. I told her some anecdotes of her brother, Sir Robert, whom I met on our travels, which pleased her. Jane would not talk much that night; something heavy seemed to have seized her spirits. Let Jane recollect how she once related to me the curious history and character of Percival Stockdale! It happened at the house of a friend in London, whom I shall not point out with too much particularity. Dibdin endeavoured to excite the envy of some of us litterateurs, that we were not, like him, members of the Roxburgh, which had dukes, and earls, and chancellors of the exchequer, and judges, and the great Magician of the North into the bargain!—Metropolitan.

TO A CHILD IN PRAYER

Fold thy little hands in prayer,Bow down at thy Maker's knee;Now thy sunny face is fair,Shining through thy golden hair,Thine eyes are passion-free;And pleasant thoughts like garlands bind theeUnto thy home, yet Grief may find thee—Then pray, Child, pray!Now thy young heart like a birdSingeth in its summer nest,No evil thought, no unkind word.No bitter, angry voice hath stirr'dThe beauty of its rest.But winter cometh, and decayWasteth thy verdant home away—Then pray, Child, pray!Thy Spirit is a House of Glee,And Gladness harpeth at the door,While ever with a merry shoutHope, the May-Queen, danceth out,Her lips with music running o'er!But Time those strings of Joy will sever.And Hope will not dance on for ever;Then pray, Child, pray!Now thy Mother's Hymn abidethRound they pillow in the night,And gentle feet creep to thy bed,And o'er thy quiet face is shedThe taper's darken'd light.But that sweet Hymn shall pass away,By thee no more those feet shall stay;Then pray, Child, pray!New Monthly Magazine.

SONG.

BY JAMES SHERIDAN KNOWLES

A Fair lady looks out from her lattice—but whyDo tears bedim that lady's eye?Below stands the knight who her favour wears,But be mounts not the turret to dry her tears;He springs on his charger—"Farewell;—he is gone,And the lady is left in her turret alone."Ply the distaff, my maids—ply the distaff—beforeIt is spun, he may happen to stand at the door."There was never an eye than that lady's more bright,—Why speeds then away her favour'd knight?The couch which her white fingers broider'd so fair,Were a far softer seat than the saddle of war;What's more tempting than love? In the patriot's sightThe battle of freedom he hastens to fight;"Ply the distaff, my maids—ply the distaff—beforeIt is spun, he may happen to stand at the door."The fair lady looks out from her lattice, but nowHer eye is as bright as her fair shining brow:And is sorrow so fleeting?—Love's tears—dry they fast?The stronger is love, is't the less sure to last?Whose arm sees her knight round her waist?—'Tis his own;By the battle she wept for, her lover is won;"Ply the distaff, my maids, ply the distaff no more;Would you spin when already he stands at the door?"Monthly Magazine.

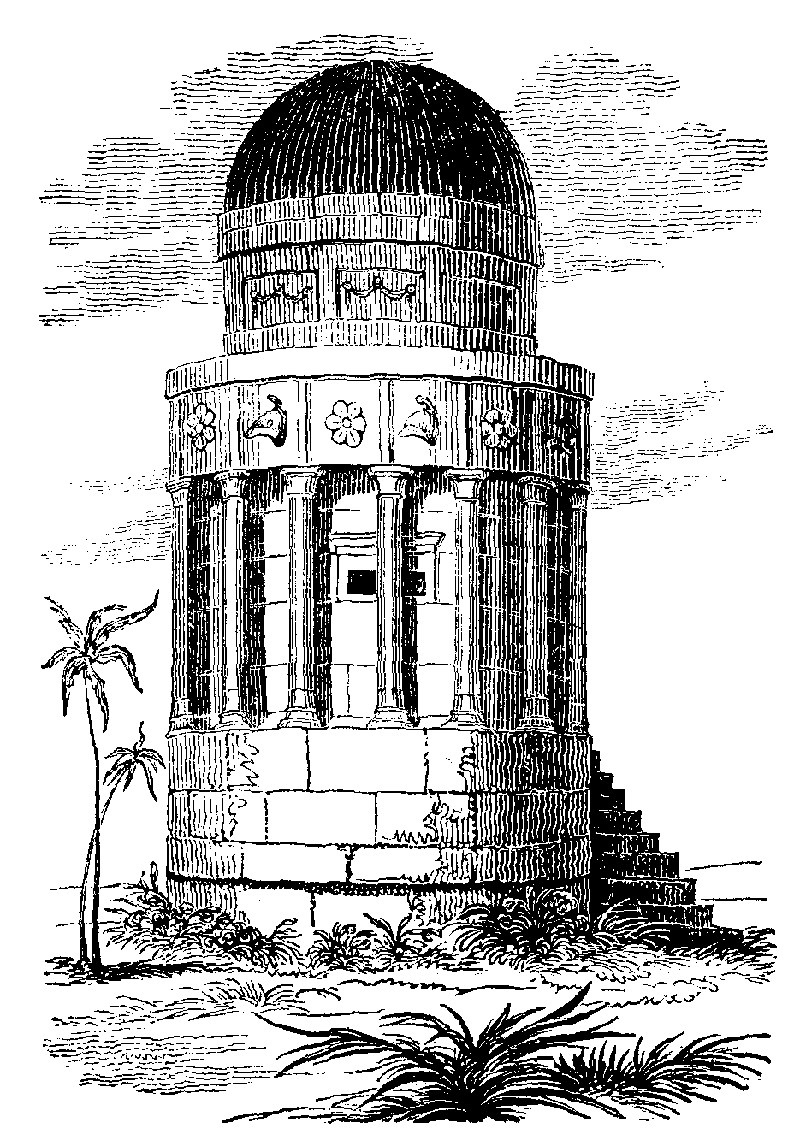

LORD CORNWALLIS'S MONUMENT, IN INDIA

The annexed cut represents the mausoleum of the Marquess of Cornwallis, whose distinguished connexion with the success of British arms in India will be recollected by the reader. It stands at Ghazepoor, a large town or city, in the province of Benares, on the river Ganges, about 450 miles from Calcutta. His lordship died on the river in the year 1805, while proceeding to make the requisite arrangements for some ceded prisoners. He was, at the time, governor-general of India, having been appointed to succeed the Marquess Wellesley, in 1804. The last act of his life accords with his general activity and vigilance, for he always gave his instructions in person, and attended to the performance of them. His personal character was amiable and unassuming, and if his talents were not brilliant, his sound sense, aided by his laudable ambition and perseverance, effected much good.

The monument is built of stone, and cost a lac of rupees, or 10,000l. It is surrounded by an iron railing, and its vicinity is the favourite promenade of the gentry of Ghazepoor, which has been termed the Montpellier of India.

Bishop Heber, in his interesting Journey through India, objects to the architectural taste of the monument in these critical observations:

"During our drive this evening I had a nearer view of Lord Cornwallis's monument, which certainly does not improve on close inspection; it has been evidently a very costly building; its materials are excellent, being some of the finest free-stone I ever saw, and it is an imitation of the celebrated Sibyl's temple, of large proportions, solid masonry, and raised above the ground on a lofty and striking basement. But its pillars, instead of beautiful Corinthian well-fluted, are of the meanest Doric. They are quite too slender for their height, and for the heavy entablature and cornice which rest on them. The dome instead of springing from nearly the same level with the roof of the surrounding portico, is raised ten feet higher on a most ugly and unmeaning attic story, and the windows (which are quite useless) are the most extraordinary embrasures (for they resemble nothing else) that I ever saw, out of a fortress. Above all, the building is utterly unmeaning, it is neither a temple nor a tomb, neither has altar, statue, nor inscription. It is, in fact, a 'folly' of the same sort, but far more ambitious and costly, than that which is built at Barrackpoor, and it is vexatious to think that a very handsome church might have been built, and a handsome marble monument to Lord Cornwallis placed in its interior, for little more money than has been employed on a thing, which, if any foreigner saw it, (an event luckily not very probable) would afford subject for mockery to all who read his travels, at the expense of Anglo-Indian ideas of architecture. Ugly as it is, however, by itself, it may yet be made a good use of, by making it serve the purpose of a detached 'torre campanile' to the new church which is required for the station; to this last it would save the necessity of a steeple or cupola, and would much lessen the expense of the building."

THE NATURALIST

We quote these Facts from the Correspondence of the Magazine of Natural History for May.

Luminous appearance on the ears of a Horse.

When we cannot find a satisfactory solution for any puzzling occurrence which we are desirous of investigating, perhaps the best way is to endeavour to accumulate a series of facts of the same kind. Some years ago, I was riding from Edinburgh: it was (as I happen to recollect) on the 12th of November, and in the evening. There had been, since past midday, a succession of those stormy clouds, driven by a westerly wind, which are common at that season. Perhaps the wind was a point or two to the north of west, if it makes any difference, and during the intervals there was always a comparative calm or slackening of the wind. I was once taken by one of these storm-clouds about Nether Libberton, on the Dalkeith road. I used the spur a little; and, having been a yeoman for many years, I was unconsciously holding a small rattan cane somewhat after the mode of "carry swords." Roused by the velocity of the wind, and the darkness of the passing cloud, I naturally turned my eyes to the right, and was not a little surprised to observe a pale clear flame, in form like that of a small candle, playing upon the point of the cane. Taking it for granted, forthwith, that a stream of electricity, attracted by the cane, was passing from the cloud through my body, and through the horse, into the ground, I instantly turned it downwards. At the time I did not wait to consider that I was in the hollow of the valley between one of the highest of the Pentlands and Arthur's Seat, and that there were higher objects than myself, and scattered trees in the neighbourhood far more likely to act upon the cloud, or be exposed to its influence. A short time after this happened, I mentioned the circumstance of the flame to a friend. He told me, in return, that once, when riding between Hawick and Jedburgh, during a dark and stormy night, he was greatly annoyed, for most part of the way, by two flames, like candles, that appeared to issue from his horse's ears. He certainly is as little likely to be affected by superstition as most men; but never before having heard of such a circumstance, and the idea of electricity not then occurring to his mind, he could not help thinking that Will o' the wisp and he, hoping it was nothing worse, had got into rather too close intimacy.

Another Correspondent says this luminous "phenomenon may be often seen on a gravel walk upon a moist autumnal evening. It arises from something of a slimy nature emitted by the Scolopéndra eléctrica (one of the animals vulgarly called centipedes), which is luminous. As the animal crawls, it leaves a long train of phosphoric light behind it on the ground, which is often mistaken for the presence of a glow-worm. In all probability, one of these animals had recently crawled over the head of the horse, or rather, might be still crawling there, and the person who saw it unconsciously watched its progress."

The Short Sunfish

appears to be the name of the "Curious Fish," described by our indefatigable Correspondent, W.G.C., in The Mirror, vol. xviii. p.168, and quoted by the Editor; he mentioned the occurrence of this fish to Mr. Yarrell, who has furnished a list of references to most of the British authors by whom it has either been described or figured. (See the Magazine, p. 316.)

By the way, Bishop Heber mentions a sun-fish, or, as it is popularly called Devil-fish: it is very large and nearly circular, with vivid colours about it, and it swims by lashing the water with its tail exactly on a level with the surface.

The Char.

The char (Sálmo alpìnus L.) is found in several of the deep and rocky lakes of England: viz. Coniston in Lancashire, Windermere in Westmoreland, Buttermere and Cromackwater in Cumberland, and, I believe, in Ulswater. My observations are confined to Windermere. Windermere is fed by two streams, which unite at the head of the lake, named the Brathy and the Rothay: the bottom of the former is rocky, and that of the latter sandy. On the first sharp weather that occurs in November, the char makes up the Brathy, in large shoals, for the purpose of spawning, preferring that river to the Rothay, probably owing to the bottom being rocky, and resembling more the bottom of the lake; and it is singular that those fish which ascend the Rothay invariably return and spawn in the Brathy; they remain in this stream, and in the shallow parts of the lake, until the end of March. While spawning, their colour and spots are much darker than when in season; the mouth and fins being of a deep yellow colour; and they are covered with a thick slime at this time. In the water before Brathy Hall, at Clappersgate, hundreds may be seen rubbing and rooting at the bottom, endeavouring to free themselves from the slime, and probably insects that annoy them. Great quantities are caught during the spawning time, by the netters, for potting, and some are sent up fresh for the London market; but those only who have eaten char in summer, on the spot, when they are in season, can tell how superior they are to those eaten in London in the winter. About the beginning of April, when the warm weather comes in, they retire into the deep parts of the lake; where their principal food is the minnow ( Cyprinus Phòxinus, L.), of which they are very fond. At this time, they are angled for by spinning a minnow; but, in a general way, the sport is indifferent, and the persevering angler is well rewarded if he succeed in killing two brace a day. A more successful mode of taking them is by fastening a long and heavily leaded line, and hook baited with a minnow, to the stern of a boat, which is slowly and silently rowed along: in this way they are taken during the early summer months; but when the hot weather comes in, they are seldom seen. They feed, probably, at night; and although they never leave the lake, except during the period of spawning, nothing is more uncommon than taking a char in July and August. When in season, they are strong and vigorous fish, and afford the angler excellent sport. They differ little in size, three fish generally weighing about 2lbs.: occasionally, one is caught larger, but they seldom vary more than an ounce. The char, as it is well known, is a singularly beautiful fish, and is accurately described by Pennant. The fishermen about the lakes speak of two sorts, the case char and the gilt char; the latter being a fish that has not spawned in the preceding season, and on that account said to be of a more delicate flavour, but in other respects there is no difference.

DUTCH RUSHES

The Equisètum hyemàle, is commonly sold under the name of Dutch rushes, for the purpose of polishing wood and ivory. If the rush be burnt carefully, a residuum of unconsumable matter will be left, and this held up to the light will show a series of little points, arranged spirally and symmetrically, which are the portions of silex the fire had not dissipated; and it is this serrated edge which seems to render the plant so efficient in attrition. Wheaten and oaten straw are also found by the experience of our good housewives to be good polishers of their brass milk vessels, without its being at all suspected by them that it is the flint deposited in the culms which makes it so useful.—Magazine of Natural History, March.

WOLF-DOG

In Hutton's Museum at Keswick, is a large stuffed dog (very much resembling a wolf, and having its propensities), which some years ago spread devastation amongst the flocks of sheep in this neighbourhood: a reward was offered for its destruction, and, though hunted by men and dogs, its caution and swiftness eluded their pursuit, till it was found asleep under a hedge, and in that position shot.—Corresp. Mag. Nat. Hist.

DUCKS

"While our voiturier," says Mr. Bakewell, "was resting his horses at Villeneuve, I observed a singular instance of sagacity in some ducks that were collected under the carriage. On our throwing out pieces of hard biscuit, which were too large for them to swallow whole, they made many efforts to break them with their beaks; failing in this, the younger ones gave up the spoil, but some of the older ducks carried parts of the biscuit to a pool of standing water, and held them to soak, till sufficiently soft to be broken and swallowed with great facility. I must leave it to metaphysicians to determine whether this process was the result of induction or instinct."

POISON OF TOADS

The circumstance of toads spitting poison, is mentioned in M.L.B's. interesting paper on the Superstitions relative to Animals. The following is the opinion of Dr. E.J. Clark on this subject, delivered at a recent lecture. S.H.

"The opinions of the vulgar are generally founded upon something. That the toad spits poison has been treated as ridiculous; but though it may be untrue that what the creature spits affects man, yet I am of opinion that it does spit venom. A circumstance related to me by a friend of mine, has tended to strengthen my opinion. He was a timber merchant, and had a favourite cat who was accustomed to stand by him while he was removing the timber; when, (as was often the case) a mouse was found concealed among it, the cat used to kill it. One day the gentleman was at his usual employment, and the cat standing by him, when she jumped on what he supposed to be a mouse, and immediately uttered aloud cry of agony; she then stole away into a corner of the yard, and died in a few minutes. It turned out that she had jumped on a toad."

THE SELECTOR; AND LITERARY NOTICES OF NEW WORKS

SCRIPTURAL ANTIQUITIES

(Concluded from page 411.)Phenomenon of the Rainbow.

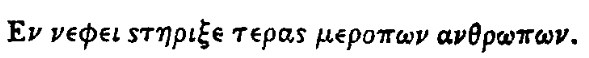

It seems to us very probable, that the density of the atmosphere was changed at the deluge, having been considerably attenuated, nor can this inference be regarded in the light of mere speculation: there seems sufficient evidence that it really must have been so. The rainbow appearing for the first time—the abbreviation of human life, and the diminished size of animal and vegetable forms, all seem to require this condition. Far be it from us to doubt the direct interposition of JEHOVAH in this catastrophe, but GOD sometimes employs secondary agents to effect his designs. "I do set," says the ALMIGHTY, "my bow in the cloud, and it shall be for a token of the covenant between me and the earth. And it shall come to pass, when I bring a cloud over the earth, that the bow shall be seen in the cloud; and I will remember my covenant, which is between me and you, and every living creature of all flesh: and the waters shall no more become a flood to destroy all flesh." It cannot be reasonably supposed, that the rainbow ever appeared before the deluge, nor from our previous remarks, is it at all necessary to suppose it. Had the patriarchs seen this beautiful phenomenon in an antediluvian world, its recurrence after the deluge could not have been a symbol of security, since, though the spectacle had been already witnessed, the deluge had supervened; but it was a new phenomenon, the consequence of the altered condition of the atmosphere, and was perhaps the result of a super-added law. The design implies stipulations of a somewhat similar description, and even pagan testimony might be cited as concurring in this view of it.

5

"Jove's wondrous bow of three celestial dies,Plac'd, as a sign to man, amidst the skies."The Fall of Manna.

This remarkable and providential supply is thus described: "When the dew that lay was gone up, behold upon the face of the wilderness there lay a small round thing, as small as the hoar-frost, on the ground." We are further told, that "when the sun waxed hot it melted;" and when preserved until the following day it became corrupt, and "bred worms." To preserve the extra measure which they collected on the sixth day, Moses directed that on that day of the week they were "to bake and seethe" what should be required on the morrow, as on the sabbath none should fall. It is further added,—"And the house of Israel called the name thereof manna: and it was like coriander-seed, white; taste of it was like wafers made with honey." Such are the curious and interesting particulars supplied by the Sacred Text. It is well known that a substance is used in medicine under this name, chiefly obtained from the Calabrias, and is collected from the leaves of the ornus rotundifolia, (fruxinas ornus, of Linnaeus,) and a somewhat similar substance obtains in the onion; but from its purgative qualities, it is sufficiently obvious that the manna of the Scriptures is altogether different. According to Seetzen, Wortley Montague, Burckhardt, and other travellers, a natural production exudes from the spines of a species of tamarix, in the peninsula of Sinai. It condenses before sunrise, but dissolves in the sun-beam. "Its taste," it is added, "is agreeable, somewhat aromatic, and as sweet as honey. It may be kept for a year, and is only found after a wet season." The Arabs collect it and use it with their bread. In the vicinity of Mount Sinai, where it is most plentiful, the quantity collected in the most favourable season does not exceed six hundredweight. The author of the "History of the Jews" has a note to the following effect: "The author, by the kindness of a traveller, recently returned from Egypt, has received a small quantity of manna; it was, however, though still palatable, in a liquid state, from the heat of the sun. He has obtained the additional curious fact, that manna, if not boiled or baked, will not keep more than a day, but becomes putrid and breeds maggots. It is described as a small round substance, and is brought in by the Arabs in small quantities mixed with sand." It would appear from these very interesting facts, that this exudation, which transpires from the thorns or leaves of the tamarix, is altogether different from the manna of the manna-ash. We cannot doubt, from the entire coincidence in every respect, that the manna found in the wilderness of Sinai by the Arabs now, is identical with that of the Scriptures. That the minute particulars recorded should be every whit verified by modern research and discovery, is worthy of great attention. As Moses directed Aaron to "take a pot and put an omer full of manna therein, and lay it up before the LORD, (in the ark,) to be kept for the generations of Israel," as a memorial; so the remarkable phenomenon remains in evidence of the truth of the narrative. The miracle, however, remains precisely as it was. There is sufficient to appeal to, as an existing and perpetual memorial to all generations. The MIRACLE, from which there can be no appeal, and which allows of no equivocation, consisted in its ample abundance, in its continued supply, and its complete intermission on the sacred day of rest. Nutritious substances have fallen from the atmosphere in some countries; such, for example, was that which fell a few years ago in Persia, and was examined by Thenard. It proved to be a nutritious substance referable to a vegetable origin. We have before us, at the moment of writing these pages, a small work, printed at Naples in 1793, the author of which is Gaetano Maria La Pira; it is entitled, "Memoria sulla pioggia della Manna," &c.: and describes a shower of manna which fell in Sicily, in the month of September, 1792. The author, a professor of chemistry, at Naples, gives an interesting account of the circumstances under which it was found, together with a variety of interesting particulars, some of which we shall select, and we do so to prove that a similar substance may have an aerial origin, though carried up in the first instance, it may be, by the process of evaporation;—this would considerably modify the product. On the 26th September, 1792, a fall of manna took place at a district in Sicily, called Fiume grande; this singular shower lasted, it is stated, for about an hour and a half. It commenced at twenty-two o'clock, according to Italian time, or about five o'clock in the afternoon: the space covered with this manna seems to have been considerable. A second shower covered a space of thirty-eight paces in length, by fourteen in breadth. This second shower of manna, which took place on the following day, was not confined to the Fiume grande, but seems to have fallen in still greater abundance in another place, called Santa Barbara, at a considerable distance: it covered a space of two hundred and fifty paces in length, by fourteen paces in breadth. An individual, named Guiseppe Giarrusso, informed Sig. G.M. La Pira, that about half-past eight o'clock, A.M., he witnessed this shower of manna, and described it as composed of extremely minute drops, which, as soon as they fell, congealed into a white concrete substance; and the quantity was such, that the whole surface of the ground was covered, and presented the appearance of snow: the depth, in all cases, seems to have been inconsiderable. This aerial manna was somewhat purgative, when administered internally; and the chemical analysis of it seemed to prove, that its constituents, though somewhat different from that obtained from the ornus rotundifolia, 6 did not materially differ from the latter in its constituents. Sig. La Pira describes it of a white colour, and somewhat granular or spherical; it seems to have had some resemblance, externally, to that of the Scriptures; but it is not stated that it became corrupt on being preserved.