Полная версия

Полная версияПолная версия:

The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 19, No. 551, June 9, 1832

On the road, we passed within view of "the Briars," where the chief resided during the building of Longwood; and where he,

"Whose game was kingdoms, and whose stakes were thrones!His table earth, his dice were human bones!"played at whist with the owner, Mr. Balcombe, for sugar-plums!

ANECDOTE GALLERY

OUR ANECDOTAGE

(From the New Monthly Magazine.)Daniel De Foe said there was only this difference between the fates of Charles the First, and his son James the Second; that the former's was a wet martyrdom and the other's a dry one. When Sir Richard Steele was made a Member of the Commons it was expected from his ingenious writings that he would have been an admirable orator, but it not proving so, De Foe said "He had better have continued the Spectator than the Tatler."

The local designation of the following anecdote confirms its authenticity, which however required no other indication than the characteristic humour of Addison in his odd conception of old Montaigne.

When Mr. Addison lodged in Kensington Square, he read over some of "Montaigne's Essays," and finding little or no information in the chapters of what their titles promised, he closed the book more confused than satisfied.

"What think you of this famous French author?" said a gentleman present.

"Think!" said he, smiling. "Why that a pair of manacles, or a stone doublet would probably have been of some service to that author's infirmity."

"Would you imprison a man for singularity in writing?"

"Why let me tell you," replied Addison, "if he had been a horse he would have been pounded for straying, and why he ought to be more favoured because he is a man, I cannot understand."

A medical confession, frankly delivered by that eminent physician and wit, Sir Samuel Garth, has been fortunately preserved; perhaps the truth it reveals is as conspicuous as its humour.

Dr. Garth (so he is called in the manuscript) who was one of the Kit-Kat Club, coming there one night, declared he must soon begone, having many patients to attend; but some good wine being produced he forgot them. When Sir Richard Steele reminded him of his appointments, Garth immediately pulled out his list, which amounted to fifteen—and said, "It's no great matter whether I see them to-night or not, for nine of them have such bad constitutions, that all the physicians in the world can't save them, and the other six have so good constitutions that all the physicians in the world can't kill them."

Sir Godfrey Kneller latterly painted more for profit than for praise, and is said to have used some whimsical preparations in his colours which made them work fair and smoothly off, but not endure. A friend noticing it to him said, "What do you think posterity will say, Sir Godfrey Kneller, when they see these pictures some years hence?"

"Say!" replied the artist: "Why they'll say Sir Godfrey Kneller never painted them!"

An extraordinary prosecution for a singular libel occurred under the administration of the Duke of Buckingham. Some fiddlers at Staines were indicted for singing scandalous songs of the Duke. The songs also did not fail to libel both James and Charles. The Bench were puzzled how to proceed. The offensive passages they would not permit to be openly read in court, lest the scandals should spread. It was a difficult point to turn. They were anxious that the people should see that they did not condemn these songs without due examination. They hit upon this expedient. Copies of the songs were furnished to every Lord and Judge present; and the Attorney-General in his charge, when touching on the offending passages, did not, as usual, read them out, but noticed them by only repeating the first and the final lines, and when he had closed they were handed to the fiddlers at the bar, interrogating them whether these were not the songs which they had sung of the Duke? To this they confessed, and were condemned in a heavy fine of 500l. and to be pilloried and whipped.

This novel and covert mode of trial excited great discontent among the friends of civil freedom. It was asserted, that all trials should be open, and that a court of justice was always a public place, where the judges publicly delivered the reasons and the grounds of their judgment. The mode now resorted to, was turning a court of judgment into a private chamber, and excluding the hearers from understanding the reasons of every judge's opinion, and the court themselves from hearing each other's. It was farther alleged, that in the present case, the Lords could not be sure that the copies showed to the prisoners were the same as that which each had before him, or that every Lord had looked into the same paper which was showed to the fiddlers, so that they might be condemned for that in which they stood not implicated.—I suppose this singular case of the Fiddlers of Staines, to be unique, and never to have been perpetuated in any of our law books.

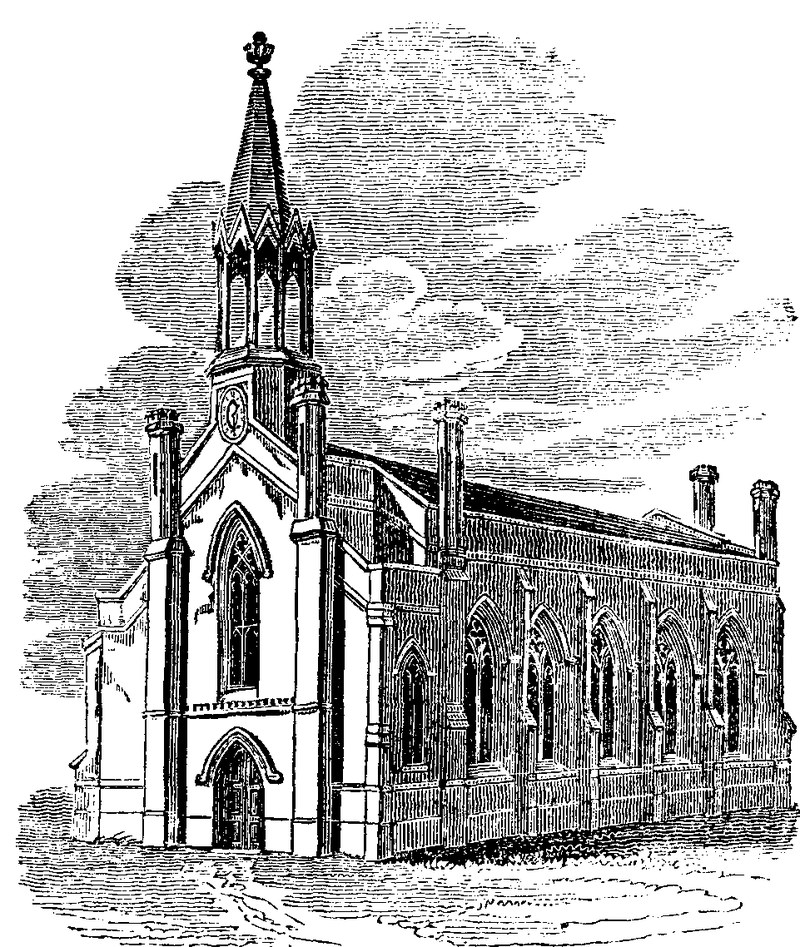

CHAPEL OF ST. JOHN THE BAPTIST, AT HAMPTON WICK

Hampton Wick is a cheerful little village in Middlesex, at the foot of Kingston Bridge. This Chapel occupies a prominent position on a road lately formed through the village, having its western front towards Bushy Park and the road leading to Hampton Court. The character of the building is the modern Gothic, forming an agreeable elevation, without any display of ornament. The building is faced with Suffolk brick and Bath stone. The interior dimensions are sixty-five feet by forty-three feet, with galleries on three sides, and a handsome recessed window over the altar-piece at the east end. The principal timbers of the roof are formed into Gothic perforated compartments, which give an addition of height to the Chapel, and an airy, decorative ceiling, at a small expense. The Chapel is calculated to contain eight hundred sittings, of which four hundred are free and unappropriated; and great benefit is anticipated from its erection in this populous neighbourhood, the parish church being at the distance of two miles and a half from the hamlet. The architect was Mr. Lapidge, who built Kingston Bridge, in the immediate vicinity. Mr. Lapidge generously gave the site, and inclosed one side of the ground at his own expense. The building was defrayed by a parliamentary grant from His Majesty's Church Commissioners, on an understanding with the parishioners, that the Church at Hampton should, at the same time, be enlarged by the parish. The cost of the Chapel and the inclosure of the site was about £4,500.

The first stone was laid on the 7th of October, 1829, and the building was finished previous to the 8th of November, 1830. The Hamlet of Hampton Wick has been since made a District for Ecclesiastical purposes, whereby the Chapel has become the Church of that District.

THE TOPOGRAPHER

TUNBRIDGE WELLS

In our last volume we noticed the announcement of a volume of Descriptive Sketches of Tunbridge Wells, by Mr. Britton: and here it is, with prints and plans, and a deep roseate binding—one of the most elegant volumes of the season, and yet purchasable for a crown. We did not expect a dull, unsatisfactory guidebook—a mere finger-post folio—nor has the author produced such a commonplace volume. Hence these "Sketches" have much of the neatness and polish, the patient investigation and research of an author who has delighted in attachment to his subject. The work contains a few of the scenes and objects of the road from London to the Wells in outline; a panoramic sketch of the Wells; the olden characteristics; and the modern improvements, including the Calverley Park estate; the natural history of the district, including the air, water, and diseases for which the water is recommended by Dr. Yeats; and the geological features of the country, from the able pen of Mr. Gideon Mantell, of Lewes; lastly, brief notice of seats, scenes, and antiquities in the environs of the Wells.

Of Tunbridge Wells, as an olden and modern resort, we have very recently spoken,6 and we are happy to perceive that the association of the place with the literary characters of the last century, as pleasantly recorded by Samuel Richardson, has been turned to interesting account in the pages before us. Cumberland, the dramatist, we omitted to mention, not only resided for some years, but wrote many of his works, at Tunbridge Wells: and here he recognised the sterling talent of Dowton, the comedian, who, through Cumberland, was first introduced to the London stage. "One of the houses at Mount Ephraim, (at the Wells,) adjoining the Tunbridge Ware manufactory, formerly belonged to the infamous judge Jeffries;" and an adjoining house was built by Sir Edmund King, physician to Charles II., and his frequent residence here probably attracted the court. The antiquities of the environs are very attractive. On a lofty knoll are the remains of an ancient encampment, called Saxon-bury Castle, from its name, ascribed to the Saxons; a neighbouring spot bears the name of Dane's Gate, and is supposed to be part of an old trackway or military road. "On Edridge Green continued, for many years, a curious mortar or large gun, said to have been the first made in England. The tradition is that it was cast at Buxted furnace about twelve miles north of Lewes. It is preserved in the British Museum; and some account of it, with a print, is given in the Archaeologia, vol. x. p. 472." Next is the estate of Edridge, among the lords of which were Godwin, Earl of Kent and the Earl of Montaigne and Cornwall: Mayfield, was possessed by the see of Canterbury before the Norman conquest, and at its palace Sir Thomas Gresham lived in sumptuous style, and probably entertained Queen Elizabeth in one of her progresses; among the curiosities here the anvil, hammer, and tongs, which are traditionally said to have belonged to the noted St. Dunstan, "and, who is also said to have used the last instrument most ungallantly, and even brutishly, in twinging the nose of Old Nick, who tempted the immaculate prelate in the form of a fine lady;" Bayham, or Bageham Abbey, about 6 miles south-east of the Wells, was a monastery of great extent in 1200, but is now so dilapidated and overgrown as scarcely to enable the antiquary to trace its architectural features: here too is an immense pollard ash-tree, which Gough describes, in his additions to Camden's Britannia, as being "several yards in girth, as old, if not older, than the abbey, and supposed to be the largest extant." Mr. Britton likewise noticed here a curious instance of ivy, which has not only covered nearly the whole surface of the (abbey) building, but has insinuated its treacherous branches into the joints and crevices of the masonry. "The wood," says our observant author, "has grown to a great size, and displaced columns, mouldings, mullions, &c. and thus overturned and destroyed the very objects it was intended to adorn." What a picture is this of the wild luxuriance of nature devastating the trim and chiselled glories of art! Next is Scotney Castle, the ancient part of which is said to have been a fortress in the reign of Richard II.; the moat still remains. The author hints that the tour may be advantageously extended to Bodiam Castle; Winchelsea, near which is Camber, one of the fortresses built by Henry VIII. to guard the south coast; Battle Abbey, founded by William the Norman, and calling up in review the battle of Hastings, and the Bayeaux tapestry; the Roman fort of Pevensey; and Hurstmonceaux Castle built by Roger Fiennes, treasurer to King Henry VI. Returning to the Wells, and in the more immediate vicinity, are Somer Hill, whose chase, manor, and appurtenances were conveyed by Queen Elizabeth to her favourite Dudley, Earl of Leicester, and subsequently to the widow of the magnanimous but ill-fated Earl of Essex; also, Great Bounds, of the age of Elizabeth, and conveyed to her relative Henry Cary, Lord Hunsden. Come we then to Tunbridge Castle, built by De Tonbridge, a kinsman of the Conqueror, who came with the invaders to share the spoil of their victory: "here, it is said, he congregated his retainers and vassals. These were all called into active service soon after the death of William I.," for De Tonbridge, (or Earl Clare, as he had been created,) espoused the cause of Robert Curtoise, in opposition to William Rufus, who had seized the crown. The castle is described by Mr. Britton with interesting and not dry-as-dust minuteness, although only some dilapidated and almost undefinable fragments remain. Tunbridge Priory and the Free Grammar School are next mentioned, the latter in connexion with Dr. Vicesimus Knox, who was master of the school for some years.

Let us hope that the frequenters of the Wells will not, in their grave moments, forget the olden glory of Penshurst, about six miles N.W. of the gay resort,—Penshurst, as Mr. Britton terms it, "the memorable, the once splendid, but now sadly dilapidated mansion of the Sydneys," or as Charlotte Smith sung with touching simplicity, in 1788:

Upon this spot,Ye towers sublime, deserted now and drear,Ye woods deep sighing to the hollow blast!The musing wand'rer loves to linger near,While History points to all your glories past.Yet, how can we enumerate the ancient fame of Penshurst in this brief memoir; from Sir John de Poulteney, who first embattled the mansion in the reign of Edward II:, to Sir John Shelley Sydney, the present proprietor of the estate; or how can we here describe the mansion, wherein that pains-taking investigator, Mr. Carter, in 1805, recognised the architectural characteristics of the reigns of Henry II., Richard III., Henry VIII., Elizabeth, James I. and George I. and III. But we must observe, "it is presumed, that whilst residing here, Henry VIII. became acquainted with Anne Boleyn, then living with her father at Hever Castle, in this neighbourhood." Among the more glorious events of the place, is the birth of the amiable Sir Philip Sydney here, Nov. 29, 1554, as Spencer dignified him, "the president of nobleness and chivalrie;" the celebrated Algernon; and his daughter, the Saccharissa of Waller. In this romantic retreat, Sydney probably framed his Arcadia; here he may have sung

O sweet woods, the delight of solitariness!O how much do I like your solitariness.Enough of the baronial hall at Penshurst has been spared to show the lantern for ventilation in the roof, "the original fire-hearth beneath it, with a large and-iron for sustaining the blazing log;" though of the place generally, Mr. Britton observes, "A house that has been so long deserted by its masters must exhibit various evidences of ruin and decay. Not only walls, roofs, and timbers, but the interior furniture and ornaments are assailed by moth, rust, and other destructive operations." Alas! the fittest scene of Burke's lament for chivalry would have been the hall of Penshurst. Yet, a Sir Philip Sydney exists, and has lately been honoured with some distinction, as Churchill would say, "flowing from the crown." In the park at Penshurst, is, however, one of Nature's memorials of one of her proudest sons—"a fine old oak tree, said to have been planted at Sir Philip Sydney's birth:" and in Penshurst churchyard, on the south side of the mansion, several of the Sydneys lie sleeping. Requiescant in pace.

Hever Castle, built in the reign of Edward III., already mentioned as the residence of the Boleyns, is about four miles north-west of Penshurst.

We have left ourselves but space to mention in the vicinity of the Wells, Buckhurst and Knole, magnificent seats of the Sackvilles, Earls of Dorset, whose splendid details have already filled volumes. Lastly, we promise the Wells visiter some gratification, by extending his tour to Brambletye House, memorialized in Horace Smith's entertaining novel. These few traits may serve to show the picturesqueness of the environs of the Wells, and consequently of Mr. Britton's volume; and we leave the reader with their grateful impression on his memory.

SPIRIT OF THE PUBLIC JOURNALS

TO CAROLINE, VISCOUNTESS VALLETORT

WRITTEN AT LACOCK ABBEY, JANUARY, 1832By Thomas Moore, EsqWhen I would sing thy beauty's light,Such various forms, and all so bright,I've seen thee, from thy childhood, wear,I know not which to call most fair,Nor 'mong the countless charms that springFor ever round thee, which to sing.When I would paint thee, as thou art,Then all thou wert comes o'er my heart,—The graceful child, in beauty's dawn,Within the nursery's shade withdrawn,Or peeping out,—like a young moonUpon a world 'twill brighten soon.Then next, in girlhood's blushing hour,As from thy own loved Abbey-towerI've seen thee look, all radiant, down,With smiles that to the hoary frownOf centuries round thee lent a ray,Chacing ev'n Age's gloom away;—Or, in the world's resplendent throng,As I have mark'd thee glide along,Among the crowds of fair and greatA spirit, pure and separate,To which even Admiration's eyeWas fearful to approach too nigh;—A creature, circled by a spellWithin which nothing wrong could dwell,And fresh and clear as from the source,Holding through life her limpid course,Like Arethusa through the sea,Stealing in fountain purity.Now, too, another change of light!As noble bride, still meekly bright,Thou bring'st thy Lord a dower aboveAll earthly price, pure woman's love;And show'st what lustre Rank receives,When with his proud Corinthian leavesHer rose, too, high-bred Beauty weaves.Wonder not if, where all's so fair,To choose were more than bard can dare;Wonder not if, while every sceneI've watch'd thee through so bright hath been,Th' enamour'd Muse should, in her questOf beauty, know not where to rest,But, dazzled, at thy feet thus fall,Hailing thee beautiful in all!Metropolitan.PROGRESS OF CRIME

(From a paper in Fraser's Magazine, entitled the Schoolmaster in Newgate—evidently from the hand of a shrewd observer, and the result of considerable experience and laborious investigation.)

By a reference to the Old Bailey session calendar, it will be seen that about 3,000 prisoners are annually committed to Newgate, making little short of 400 each session, of which there are eight in a year. Out of the gross number, about 350 are discharged by proclamation. Of these nothing can be said, as they must be considered innocent of the crimes with which they were charged, there not being primâ facie evidence to send them on their trials. There remain 2,550 who are tried, with the progressive increase of 4-7ths annually. Some persons have supposed this accumulation of offenders bears a regular proportion to the progress of population. As well may they assert that the demand for thieves in society regulates the supply, as in other markets of merchandise. The cause is in the maladministration of the laws—the sending out so many old offenders every session to teach and draw in the more juvenile and less experienced hands—with the uncertainty of punishment, by the inequality of sentences for crimes of a like nature—to which may be added the many instances of mistaken, or rather mis-directed leniency, compared with others of enormous severity for trifling offences; all which tend to induce the London thieves to entertain a contempt for that tribunal. An opinion prevails throughout the whole body, that justice is not done there. I do not mean to say they complain of the sentences being too severe generally; that would be natural enough on their parts, and not worth notice. They believe everything done at that court a matter of chance; that in the same day, and for a like crime, one man will be sentenced to transportation for life, while another may be let off for a month's imprisonment, and yet both equally bad characters.

It only needs that punishment should be sure to follow the conviction for crime, and that the judgments should be uniform and settled, to strike terror into the whole body of London criminals. Out of the 2,550 annually tried, nearly one-fourth are acquitted, leaving little short of 2,000 for sentence in each year. Of these the average transported are 800; deduct 200 for cases of an incidental nature, i.e. crimes not committed by regular offenders, and there remain 1,000 professed thieves who are again turned loose in a short period on the town, all of whom appear in due course again at the court of the Old Bailey, or at some other, many times in the revolution of one year. Here lies the mischief. An old thief will be sure to enlist others to perpetuate the race. There is no disguising the fact: the whole blame is with the court whose duty it is to take cognizance of these characters. Whilst the present system is pursued, of allowing so many old offenders to escape with trifling punishments, the evils will be increased, and the business of the court go on augmenting, by its own errors. The thief is now encouraged to speculate on his chances—in his own phraseology, "his good luck." Every escape makes him more reckless. I knew one man who was allowed a course of seventeen imprisonments and other punishments before his career was stopped by transportation; a sentence which does, however, sooner or later overtake them, and which would be better both for themselves and the country were it passed the first time they were in the hands of the court as known thieves. Observing only a certain, and nearly an equal, number transported each session, they have imbibed a notion, that the recorder cannot exceed it, and that he selects those to whom he takes a dislike at the bar, not for the magnitude of their offence, but from caprice or chance. It is under this impression they are afraid of speaking when in court, lest they should give offence, and excite petulance in the judge, which would, in their opinion, inevitably include them in the devoted batch of transports, of which their horror is inconceivable; 1st, because many have already undergone the punishment; and 2dly, all who have not are fully aware of the privations to which it subjects them. Their anxious inquiry regarding every particular relating to the treatment, is a strong manifestation of their uneasiness on this subject. Yet Mr. Wontner and Mr. Wakefield (says the Quarterly reviewer) think neither transportation nor the hulks have any terrors for them. How they come to this opinion, I cannot imagine. If they draw their inference from the noise and apparent mirth of the prisoners when they leave Newgate for the hulks, I think their premises false.

The transports are taken from Newgate in parties of twenty-five, which is called a draft. When the turnkeys lock up the wards of the prison at the close of the day, they call over the names of the convicts under orders for removal, at the same time informing them at what hour of the night or morning they will be called for, and to what place and ship they are destined. This notice, which frequently is not more than three or four hours, is all that is given them; a regulation rendered necessary to obviate the bustle and confusion heretofore experienced, by their friends and relatives thronging the gates of the prison, accompanied by valedictory exclamations at the departure of the van in which they are conveyed. Before this order arrives, most of them have endured many months' confinement, and having exhausted the liberality, or funds—perhaps both—of their friends, have been constrained to subsist on the goal allowance. This, together with the sameness of a prison life, brings on a weariness of mind, which renders any change agreeable to their now broken spirits; the prospect of a removal occasions a temporary excitement, which, to those unaccustomed to reason on the matter, may appear like gaiety, and carelessness of the future. The noise and apparent recklessness, however, on these occasions, are produced more by those prisoners who are to remain behind, availing themselves of the opportunity to beguile a few hours of tedious existence by a noisy and forced merriment, which they know the officers on duty will impute to the men under orders for the ship. This is confirmed by the inmates of the place being, on all other nights of the year, peaceable after they have been locked up in their respective wards. Those who suppose there is any real mirth or indifference among them at any time, have taken but a superficial view of these wretched men. Heaviness and sickness of heart are always with them; they will at times make an effort to feel at ease, but all their hilarity is fictitious and assumed—they have the common feelings of our nature, and of which they can never divest themselves. Those who possess an unusual buoyancy of spirits, and gloss over their feelings with their companions, I have ever observed on the whole, to feel the most internal agony. I have seen upwards of two thousand under this sentence, and never conversed with one who did not appear to consider the punishment, if it exceeded seven years, equal to death. May, the accomplice of Bishop and Williams, told me, the day after his respite, if they meant to transport him, he did not thank them for his life. The following is another striking instance of the view they have of this punishment. A man named Shaw, who suffered for housebreaking about two years since, awoke during the night previous to his execution, and said, "Lee!" (speaking to the man in the cell with him) "I have often said I would be rather hanged than transported; but now it comes so close as this, I begin to think otherwise." Shortly afterwards he turned round to the same man and said, "I was wrong in what I said just now; I am still of my former opinion: hanging is the best of the two;" and he remained in the same mind all the night. The first question an untried prisoner asks of those to whom he is about to entrust his defence is, "Do you think I shall be transported? Save me from that, and I don't mind any thing else." One thing, however, is clear: no punishment hitherto has lessened the number of offenders; nor will any ever be efficient, until the penalties awarded by the law unerringly follow conviction, especially with the common robbers.